22.03.2018

Silicon Valley start-up’s SpaceBees are being tracked on orbit, but they could be the company’s last

Nearly two weeks after IEEE Spectrum broke the news that Swarm Technologies had carried out the first ever unauthorized satellite launch, mystery surrounds the company’s reasons for doing so. And uncertainty clouds the air around it because it’s not clear what the consequences for the stealthy start-up might be.

For the past two years, the company has been working on four small SpaceBee satellites, prototypes for an innovative constellation it believes will enable Internet of Things data communications for as little as one-hundredth the cost of existing services.

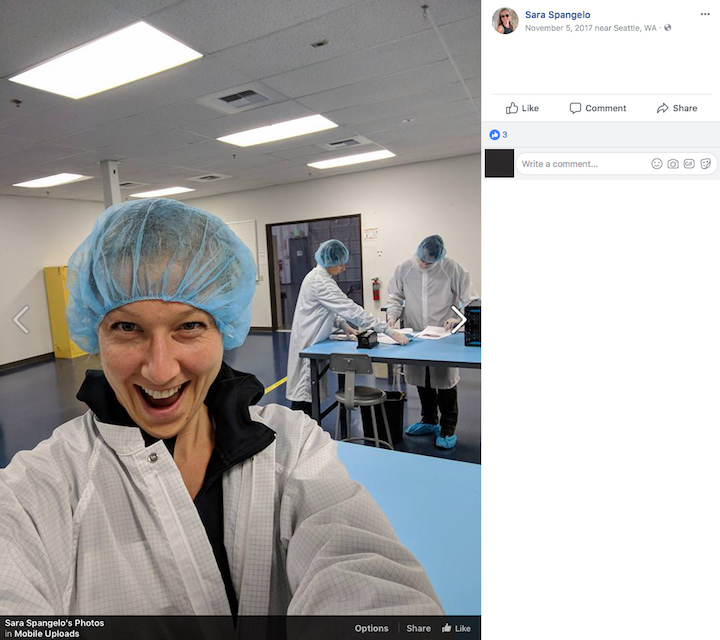

In November, Swarm’s founder, Sara Spangelo, delivered the four satellites to Spaceflight, a company in Seattle that consolidates multiple small satellites (often called Cubesats) for launch alongside larger payloads. The satellites then made their way to India, so they could be loaded aboard a Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) operated by Antrix, the commercial launch arm of India’s space agency.

Photo: Sara Spangelo/Facebook; Screenshot: IEEE SpectrumThis photograph, dated 5 Nov. 2017 and geotagged as having been taken in Seattle, was posted on Facebook by Swarm’s founder Sara Spangelo.

-

However, a month after Spangelo’s Seattle trip, Swarm heard troubling news from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC); the agency had rejected the company’s application for a launch license. The FCC feared that the tiny satellites would be difficult to track on orbit, and therefore pose a hazard to other satellites and spacecraft.

“[Swarm’s founders] called me for advice and mentioned they were having trouble with the FCC approving things,” says a senior industry figure who is actively involved in launching small satellites, but who asked to remain anonymous to protect his relationship with the U.S. government. “I suggested they get in touch with lawyers that specialize in this stuff and gave them a reference to a couple that we use.”

Whether or not Swarm followed this advice is unknown; Spangelo did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Social Capital, a Silicon Valley venture capital fund whose social media activity suggests that it has invested in Swarm, did not reply either. We weren’t the only ones to get the silent treatment. Swarm did not engage in any further correspondence with the FCC, and the PSLV launch went ahead as planned on 12 January, with the four SpaceBees on board.

Back in the United States, Spangelo and the Swarm team celebrated with a party, including a bottle of champagne with the words “Swarm successful 1st launch!” scrawled on it. The company then proceeded to make further plans: the launch, in April, of four larger satellites on a Rocket Lab vehicle from New Zealand; and a market trial with two large commercial partners.

That all ground to a halt earlier this month, when the FCC told Swarm that the agency was setting aside the startup’s permission for the April mission, due to the unauthorized launch and operation of the original SpaceBees.

What remains unclear is whether Swarm actually believed it could proceed with the first launch despite having been denied a license, or simply decided to take a risk and hope that the FCC would take no action.

“[Sara] is a very careful engineer,” says the industry source, who has worked with Spangelo in the past. “I can’t imagine her deliberately ignoring rules and regulations. My suspicion is that she did what she thought was appropriate. Frankly, [getting permits] is a Byzantine process, and it’s often unclear what regulations you have to follow and which ones you don’t.”

Mark Sundahl, director of the Global Space Law Center at Cleveland State University, says that cutting legal corners rarely works in space: “Silicon Valley start-ups are used to not asking for permission but asking for forgiveness later. But that’s not how you operate in space. It’s a highly hazardous environment with high value assets moving at high speeds. The FCC is going to want to make an example of Swarm.”

Spaceflight told Spectrum that it would not knowingly launch a customer whose FCC license had been denied. However, its president admitted to SpaceNews at a conference last week that: “There’s room for improvement on our side. We did a lot already, but obviously we found something that wasn’t perfect, so we’ll fix it.”

In a statement, Antrix noted that its customers were responsible for obtaining all necessary permits and that it “has requested its U.S. clients to cross-check with FCC for compliance of regulations before exporting future satellites to India.” That suggests it might be more difficult for future operators to get satellites into space without the required paperwork.

Meanwhile, it appears that the FCC’s fears of not being able to track the SpaceBees could be unfounded. Daniel Ceperley, CEO of LeoLabs, a commercial satellite tracking company, told Spectrum that his company’s automated system acquired the four SpaceBees almost immediately after launch. “We are still seeing them once or twice a day,” he says. That frequency is sufficient to plot their orbits for collision avoidance.

Tracking technology is also improving rapidly. LeoLabs is upgrading its ground-based radar this year to track objects as small as 2 centimeters on a side. That improved vision will expand its orbital catalog from 13,000 objects to over 250,000. The U.S. Air Force’s Space Surveillance System should also put a higher resolution S-band radar system into operation early next year.

“Maybe Swarm can help convince the FCC that their satellites can be tracked,” says Sundahl. “If they are very honest and make the right promises to behave well in the future, then their punishment could be less drastic.”

As of today, however, Swarm’s permit to launch in New Zealand remains set aside, and Rocket Lab told Spectrum that it would only fly payloads that have all the necessary licenses. Perhaps the FCC will decide that forcing Swarm to sit out one expensive launch is punishment enough. Or perhaps not.

“This is a lesson to everyone that you need to understand the law,” says Sundahl. “In this case, violation of it will not bring a slap on the wrist, but could destroy your company.” That would obviously be the worst-case scenario for Swarm. Even if that were the company’s fate, its four SpaceBees will continue to circle the Earth for perhaps the next seven or eight years before deorbiting and burning up.

In the meantime, amateur satellite watcher Mike Coletta is keeping an eye out for possible transmissions. “I began looking for the SpaceBee signals after reading about the unauthorized launch,” he told Spectrum. “Using the published center frequency of 137.920 megahertz, my quest began. As of this date, no signals have been received by me, during any orbital pass.”

That is probably a wise move on Swarm’s part. Putting its unauthorized SpaceBees into operation could be just the sting in the tail that would tip an irate FCC over the edge.

Quelle: IEEE