5.03.2018

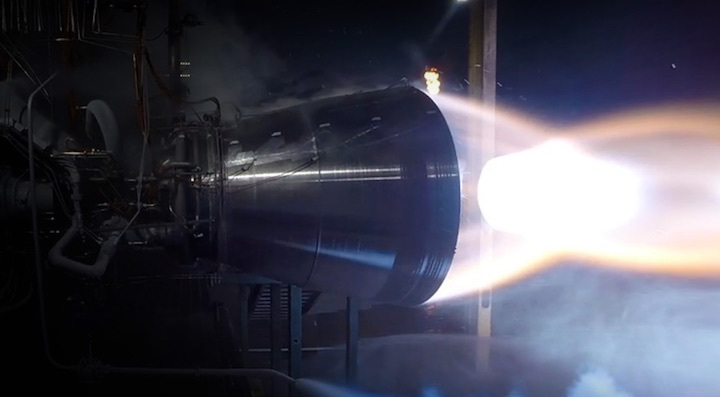

A Blue Origin BE-4 engine during its first hotfire test. Credit: Blue Origin

-

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — As Blue Origin continues tests of its BE-4 engine, United Launch Alliance is keeping quiet about when it might select that engine or an alternative for its Vulcan rocket.

Blue Origin started testing of the BE-4 in October 2017 at its West Texas test site. The company has disclosed few details about the status of that test program since then, but a company official said at the 45th Space Congress here Feb. 28 that the company was making “good progress” on tests of the engine.

“We’re getting longer duration burn times. We’re going though validating the turbomachinery very closely,” said Jim Centore, group lead for orbital mission operations at Blue Origin, during a panel discussion on launch systems at the conference.

Centore didn’t disclose many details about those tests, such as thrust levels or the burn times, either of individual tests or cumulatively. “We’re continuing to make good progress,” he said. “We’ll continue that for the next several months.”

Blue Origin is developing the BE-4 for its own New Glenn launch vehicle, with seven engines in the rocket’s first stage and one in its second. That vehicle, which will be manufactured at a factory the company recently built adjacent to the Kennedy Space Center, will be able to place up to 45 metric tons into low Earth orbit as 13 metric tons into geostationary orbit. The BE-4 engines themselves will be manufactured in a separate facility in Huntsville, Alabama.

BE-4 is also under consideration by ULA for use in the first stage of its Vulcan rocket. Company officials have long indicated that that the BE-4 was its preferred choice, but would wait on making a formal decision on whether to use the BE-4 engine until it completed a series of tests.

That decision was widely expected some time last year, but the company has not announced a decision yet. That’s raised questions about when the Vulcan itself will be complete.

Gary Wentz, vice president for government and commercial programs at ULA, said development of Vulcan remained on schedule. “We’re on target for our first flight in mid-2020,” he said during the panel discussion.

He declined later, though, to say when the company had to make a decision on an engine in order to keep on that schedule. “We’re in a competitive procurement, and we’re really not at liberty to discuss the details of what’s going on,” he said.

The choice of engine has implications for the overall design of the rocket as well as ground systems, in large part because of different propellants used. BE-4 uses methane and liquid oxygen (LOX), while Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AR1, the other engine under consideration for Vulcan, uses a refined version of kerosene known as RP-1 along with liquid oxygen.

That difference in fuels does create some complications, Wentz acknowledged. “Customers are always concerned about going from the traditional LOX/kerosene, LOX/hydrogen systems into a LOX/methane system,” he said. ULA’s Atlas 5 uses liquid oxygen and kerosene in its first stage, while the Delta 4 uses liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. “It also introduces challenges with the ground systems and compatibility.”

“The team, through the design process, has kept an open mind,” he said. “In a lot of the systems, we’re actually building a methane-compatible system in parallel with the traditional Atlas system. We’re just working through the details, working through the design and keeping the options open until we prepare to make that downselect.”

Quelle: SN