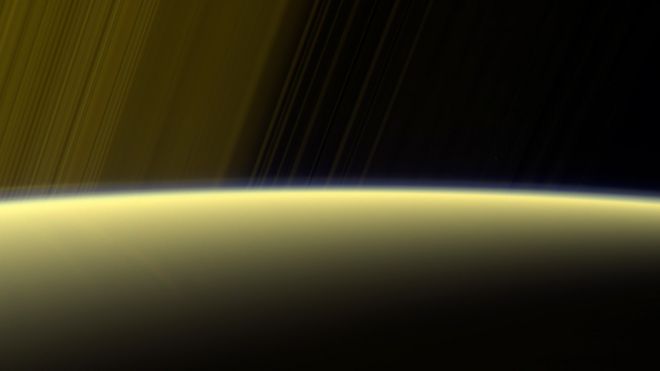

Continuing to make discoveries in the final weeks of a historic mission at Saturn, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has recorded a unique time lapse movie looking out toward the planet’s iconic icy rings.

Cassini captured imagery to assemble the movie during an Aug. 20 swing through the gap between Saturn and its rings. Ground controllers set Cassini’s wide-angle camera to take images in a low-resolution mode — 512 x 512 pixels — to allow the spacecraft to gather more photos in a short span of time, according to NASA.

“The entirety of the main rings can be seen here, but due to the low viewing angle, the rings appear extremely foreshortened,” NASA said in a statement. “The perspective shifts from the sunlit side of the rings to the unlit side, where sunlight filters through.”

The sequence shows Cassini crossing the relatively thin ring plane as it zipped by Saturn at a speed of some 76,000 mph (122,000 kilometers per hour) relative to the planet’s cloud tops.

“On the sunlit side, the grayish C ring looks larger in the foreground because it is closer; beyond it is the bright B ring and slightly less-bright A ring, with the Cassini Division between them,” NASA said. “The F ring is also fairly easy to make out.”

Running low on fuel, Cassini is set to end its nearly 20-year mission Sept. 15 with a guided plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere. The probe will disintegrate as it descends into the deeper layers of the atmosphere, succumbing to increasing aerodynamic pressures.

Composed mostly of blocks and particles of ice, Saturn’s rings are one of the major targets for Cassini’s scientific instruments during the mission’s final months. Scientists hope to learn the mass of the rings, a figure that should yield an estimate of their age and origin.

Saturn itself is also a focus during Cassini’s grand finale.

Measurements of Saturn’s gravity and magnetic fields could help scientists study the planet’s interior structure, and Cassini’s final five passes near the planet are taking the spacecraft into the outermost reaches of the atmosphere, allowing its instruments to take direct samples.

Cassini will beam back atmospheric data in real-time during its final descent into Saturn next month until the probe’s control thrusters are unable to keep the craft’s antenna locked on Earth.

Launched from Cape Canaveral in October 1997, the spacecraft spent much of its time at Saturn making observations of the planet’s numerous moons. Cassini dropped a European Space Agency lander to Titan’s surface for a parachute-assisted landing in 2005, and found evidence that Enceladus harbors a global ocean of water buried beneath a veneer of ice.

NASA officials want to end the mission in a guided manner while the spacecraft is still healthy to avoid the chance an uncontrolled Cassini could crash into Titan or Enceladus, potentially spoiling habitats that might be prime for finding alien microbial life.

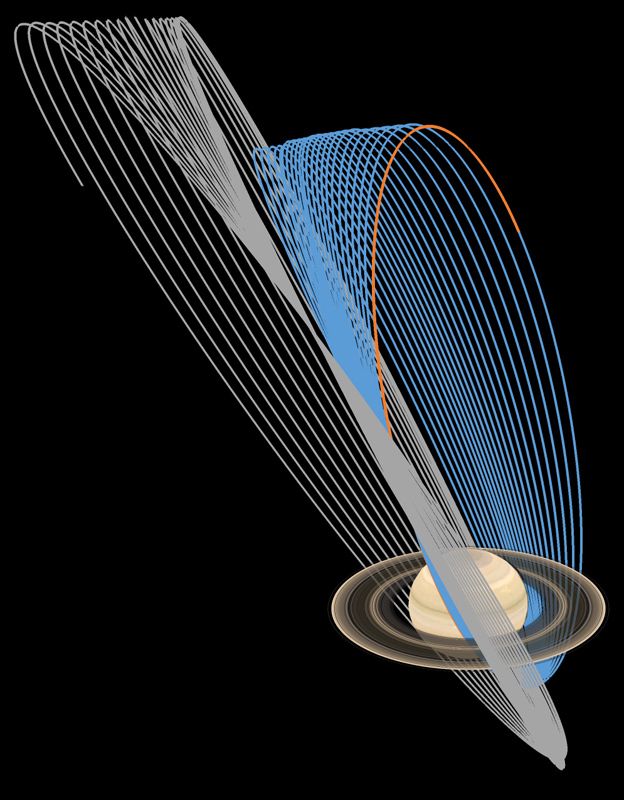

Since April, Cassini has made repeated passes between Saturn and its rings. Two more flybys are planned before the final dive Sept. 15.

Quelle: SN

---

Update: 30.08.2017

.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft nears a fiery, brutal end, when it will plunge into Saturn

After 13 years of observing Saturn, its rings and its myriad moons, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft is less than three weeks away from a fiery, brutal end.

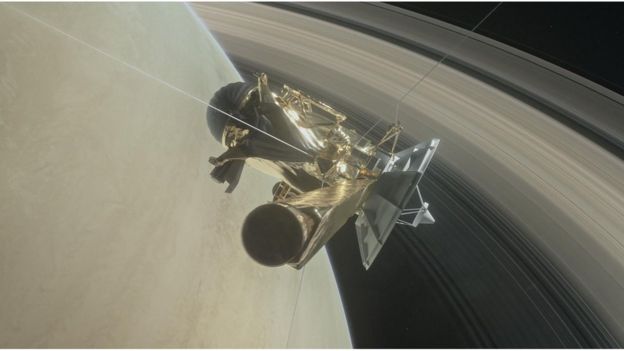

Early in the morning on Sept. 15 the aging spacecraft will hurl itself into Saturn’s atmosphere at speeds of more than 75,000 mph.

It’s a deliberate death plunge from which it has no hope of returning.

Within three minutes of diving into Saturn’s tenuous upper layers, the two-story-tall spacecraft will be torn apart.

In the end, Cassini will become part of the very planet it has studied for more than a decade.

“I like to say it’s going out in a blaze of glory,” said Linda Spilker of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the project scientist for the mission. “It will be trailblazing until the very last second.”

Earth-bound astronomers will keep a close eye on the planet at the moment of Cassini’s death to see whether they can detect a small flare as the spacecraft burns up like a meteor in the Saturnian sky.

But they don’t expect to see much.

“The mass of Cassini is so small compared to the mass of the planet,” Spilker said. “And the plunge is happening on Saturn’s day side.”

She added that there is no fear that Cassini’s death dive will contaminate the ringed giant. Molecules from the spacecraft will quickly spread out across the planet, which is big enough to hold more than 700 Earths.

Still, Cassini’s suicide mission is not all gloom and doom. The spacecraft will venture deeper into Saturn’s atmosphere than ever before, collecting brand new data and beaming it back to Earth up until the last seconds of its life.

“We are reconfiguring the spacecraft and turning Cassini into an atmospheric probe,” said Earl Maize, the mission’s program manager, who also works at JPL.

Cassini could make it as far as 120 miles into the Saturnian atmosphere before all its instruments cease to function, mission engineers said.

“I find great comfort that Cassini will continue teaching us until the very last second on Sept. 15,” said Curt Niebur, Cassini program scientist based at NASA’s headquarters in Washington.

The flagship mission launched in 1997 and entered the Saturnian system in 2004.

Over the last 13 years it has discovered plumes of water ice on the moon Enceladus, confirmed the presence of methane and ethane lakes and rivers on Titan, watched the seasons change on Saturn, discovered six new moons and revealed complexities in the planet’s rings that had never been seen before.

“We’ve rewritten the textbooks on Saturn,” Spilker said. “Literally, there are so many new books coming out.”

Although the spacecraft’s instruments continue to work flawlessly, its gas tank is nearing empty. Mission planners decided to crash Cassini into Saturn to avoid any risk of contaminating Enceladus or Titan, two of Saturn’s moons that could harbor the ingredients necessary for life.

Beginning in April, Cassini began a series of orbits that took it speeding through the gap between the planet and its rings for the first time. This has allowed scientists to address new questions including the age of the rings and how quickly the planet’s interior is spinning.

By Sept. 15, the spacecraft will have completed 22 of these orbits to collect new data even as its end looms.

“Who knows what new mysteries the next two weeks will bring?” Spilker said.