One artist’s concept of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69, the next flyby target for NASA’s New Horizons mission. This binary concept is based on telescope observations made at Patagonia, Argentina on July 17, 2017 when MU69 passed in front of a star. New Horizons theorize that it could be a single body with a large chunk taken out of it, or two bodies that are close together or even touching. Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Alex Parker

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is well over halfway between Pluto and its next historic intercept target, Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) 2014 MU69, aiming for a New Years Day flyby at 2:00 a.m. EDT on January 1, 2019. The $728 million, piano-sized 1,000 pound spacecraft will put its seven high-tech science instruments into overdrive when it flies by the tiny world, only about 20 miles across, and will do so at a much closer distance than it did Pluto – only about 1,900 miles (3,000 kilometers) from the surface.

But because it is so small and faint, much is still unknown about it, such as whether or not there are any unseen satellites, rings or other debris that could pose a danger to the spacecraft. So to make more detailed observations of the ancient object, frozen in time from the dawn of our solar system’s creation, the New Horizons team recently pulled off something incredible.

Second artist’s concept of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69, which is the next flyby target for NASA’s New Horizons mission. Scientists speculate that the Kuiper Belt object could be a single body (above) with a large chunk taken out of it, or two bodies (main image) that are close together or even touching. Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Alex Parker

They used data from both Hubble and the European Space Agency’ Gaia satellite to calculate where MU69 would cast a shadow on Earth’s surface as it passed in front of a star, and intercepted it over the Pacific Ocean onboard NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) so its flying telescope could observe the occultation to see how the light from the star changed in the process.

At the same time SOFIA was attempting to image MU69 over the Pacific, on land in Chile, the Gemini Observatory South was also attempting to do the same. A handful of telescopes were deployed in a remote part of Patagonia, Argentina as well, and their findings have returned some interesting results.

VIDEO: New Horizons 2014 MU69 Occultation Campaign (Patagonia Argentina)

“Team members say MU69 may not be not a lone spherical object, but suspect it could be an “extreme prolate spheroid” – think of a skinny football – or even a binary pair,” says NASA. “The odd shape has scientists thinking two bodies may be orbiting very close together or even touching – what’s known as a close or contact binary – or perhaps they’re observing a single body with a large chunk taken out of it.”

“This new finding is simply spectacular,” said Alan Stern, mission principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado. “The shape of MU69 is truly provocative, and could mean another first for New Horizons going to a binary object in the Kuiper Belt. I could not be happier with the occultation results, which promise a scientific bonanza for the flyby.”

Said Marc Buie, the New Horizons co-investigator who led the observation campaign, “These exciting and puzzling results have already been key for our mission planning, but also add to the mysteries surrounding this target leading into the New Horizons encounter with MU69.”

As of today, Aug 3, 2017, New Horizons is 38.18 AU from Earth (39.09 AU from Sun), and 4.30 AU from 2014 MU69. Round-trip light time between Earth and the spacecraft is currently 10:35:09, and is traveling about 32,000 mph (14.25 km/s).

Quelle: AS

---

Update: 3.09.2017

.

To Pluto and beyond

The principal investigator of NASA’s New Horizons mission is coming to UC to talk about the spacecraft’s close encounter with Pluto and its next target 4 billion miles from Earth.

NASA’s successful mission to Pluto in 2015 was spurred by a graduate student with a big idea.

Alan Stern was finishing his astrophysics degree at the University of Colorado Boulder in 1989 when he approached NASA with the notion of sending a spacecraft to Pluto.

Pluto is the farthest planet (some prefer dwarf planet) from the sun in our solar system. After NASA’s Voyager 2 probe sent back the first detailed images of Neptune from space in 1989, Pluto was an obvious target of scientific conquest. But it took more than 15 years of prodding and perseverance by Stern and other supporters to get a mission off the ground.

Today, the New Horizons spacecraft is hurtling hundreds of millions of miles past Pluto through the Kuiper Belt, a distant ring of rock and ice, where the probe will rendezvous with an asteroid-like object the size of Greater Cincinnati some 4 billion miles from Earth.

Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons and NASA’s former chief science officer, will visit UC to talk about the mission at 3 p.m., Sept. 8, at Tangeman University Center’s Great Hall.

Stern is a planetary scientist and vice president of space science and engineering at the Southwest Research Institute, a nonprofit that works with government and industry.

“When I look back, I think of all the many people who made New Horizons happen,” Stern said. “Their persistence over many difficulties and setbacks produced a breakthrough project that inspired a lot of people and shattered the mold for low-cost planetary exploration.”

Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons, talks about the 3-billion-mile mission to Pluto. (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

If you go:

NASA’s former chief science officer Alan Stern will talk about the New Horizons project at 3 p.m., Friday, Sept. 8, at UC’s Tangeman University Center Great Hall. Admission is free.

About Pluto:

• Discovered in 1930 by astronomer Clyde Tombaugh.

• Has five moons, including Charon, who in Greek mythology ferries the souls of the recently deceased over the river Styx to the land of the dead.

• Diameter of 1,475 miles, smaller than our moon.

• Ranges from 2.7 billion to 4.7 billion miles from Earth, depending on planetary orbits.

Source: NASA

UC physics professor Margaret Hanson was a classmate of Stern’s at the University of Colorado. She invited him to speak at UC. Besides the obvious interest in the project among astrophysicists, UC geologists, geographers and engineers are following the mission closely, too, she said.

“The tenacity of Alan to get this done is just incredible. It was canceled so many times, redesigned so many times. This would not have happened with anyone else,” she said.

The project endured multiple series of congressional approvals and funding cutbacks that threatened to derail it. Stern said thousands of people played a role in planning the project, building the spacecraft and its systems and executing the mission.

“It was thanks to a lot of people – and trust me, I get too much credit for this. It’s not my project. It’s our project,” he said.

A technician wraps the half-ton New Horizons spacecraft in a protective heat shield at the Kennedy Space Center. (NASA)

The spacecraft launched in 2006 and traveled uneventfully toward Pluto for more than nine years. But on Independence Day of 2015, just 10 days before New Horizons was to reach its target, the spacecraft went dark.

Stern’s team had lost communications.

“It was heart-wrenching. It was flying across the solar system for almost nine-and-a-half years, and it never had a moment like that,” Stern said.

Over the long holiday weekend, the team scrambled to diagnose the problem and figure out a solution with the prospect of failure looming as big as the approaching planet. Everyone understood the implications, but nobody panicked, Stern said.

“You really don’t have a choice. You can panic and go bounce off the walls. But after a half-hour, what are you going to do? You’re back in the same place anyway,” he said. “We’re here. This happened. Let’s buckle down and solve the problem.”

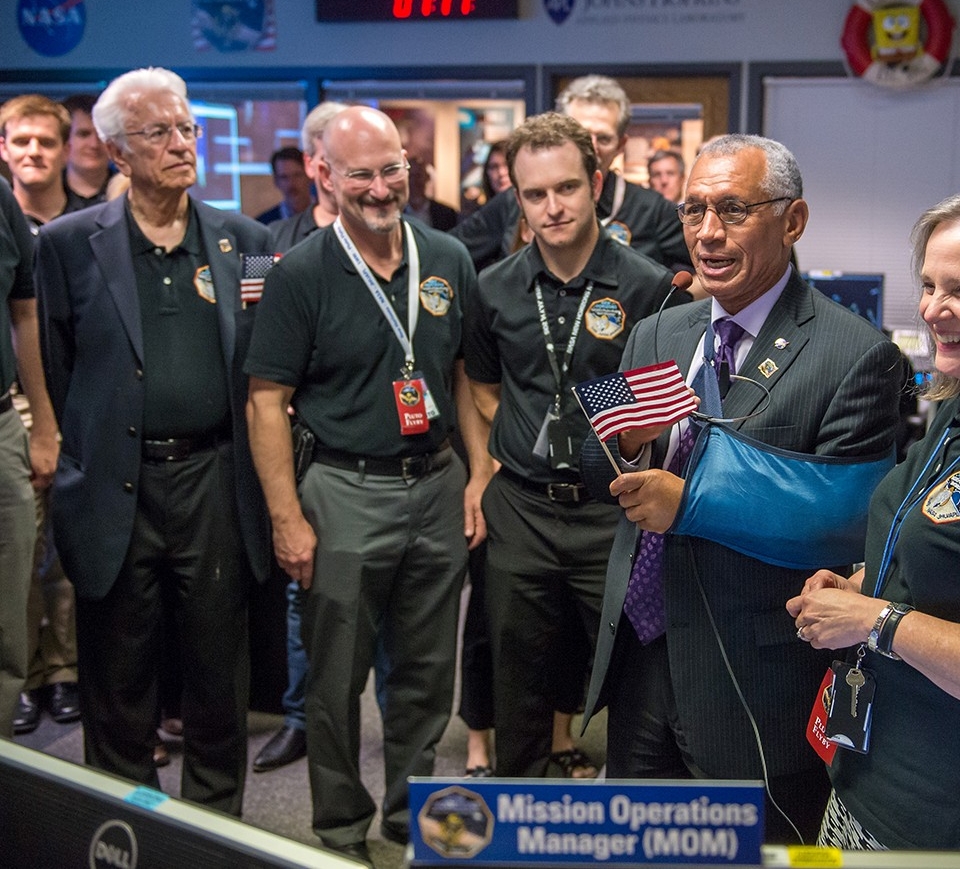

UC graduate Chris Hersman (red badge, center) celebrates the successful rendezvous of New Horizons with Pluto in 2015. (NASA)

New Horizons is carrying a Florida quarter engraved with a “Gateway to Discovery” design. Also onboard is a Pluto postage stamp from the U.S. Postal Service’s planets series. The 1991 stamp reads “Not Yet Explored.” (NASA)

'48 hours of terror'

Engineers and staff worked around the clock for days, sleeping under their desks while they puzzled over the problem. Among them was UC graduate Chris Hersman, a 1988 alum of the College of Engineering and Applied Science, who served as New Horizons’ mission systems engineer. In a 2015 UC Magazine interview, he described the crisis as “48 hours of terror.”

“These were very complex activities that under normal circumstances might have taken months to coordinate, practice and execute – all in the space of just three days,” Stern said.

The team determined that New Horizons’ computers were overloaded after it received Pluto flyby instructions while compressing data. The multiple operations caused a software conflict that prompted the computers to go into safe mode.

“Chris is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met,” Stern said. “He has the entire design of the spacecraft and how it operates in his head. There have been countless occasions where Chris’ contributions made the difference between success and failure.

“If it weren’t for Chris Hersman, there would have been no exploration of Pluto.”

UC graduate Chris Hersman, mission systems engineer for New Horizons. (NASA)

“If it weren’t for Chris Hersman, there would have been no exploration of Pluto.”

‒ Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons

Mission success

Meticulously, the team dispatched instructions to the spacecraft nearly 3 billion miles away. Each transmission took more than four hours to reach New Horizons as the spacecraft streaked toward Pluto at 32,500 miles per hour.

“We crammed months of work into those three days, with no possibility of a second chance, and got it right,” Stern said.

Communications with New Horizons sprung back to life on July 7 as if nothing had happened. Days later, the spacecraft successfully skirted past Pluto and its moons, sending back extraordinary and intimate images of Pluto’s ice-capped mountains the size of Grand Teton.

New Horizons was able to:

• Capture high-resolution photos of Pluto and its largest moon, Charon.

• Record a miles-deep canyon on Charon.

• Observe Pluto’s four other moons.

• Learn more about Pluto’s thin atmosphere.

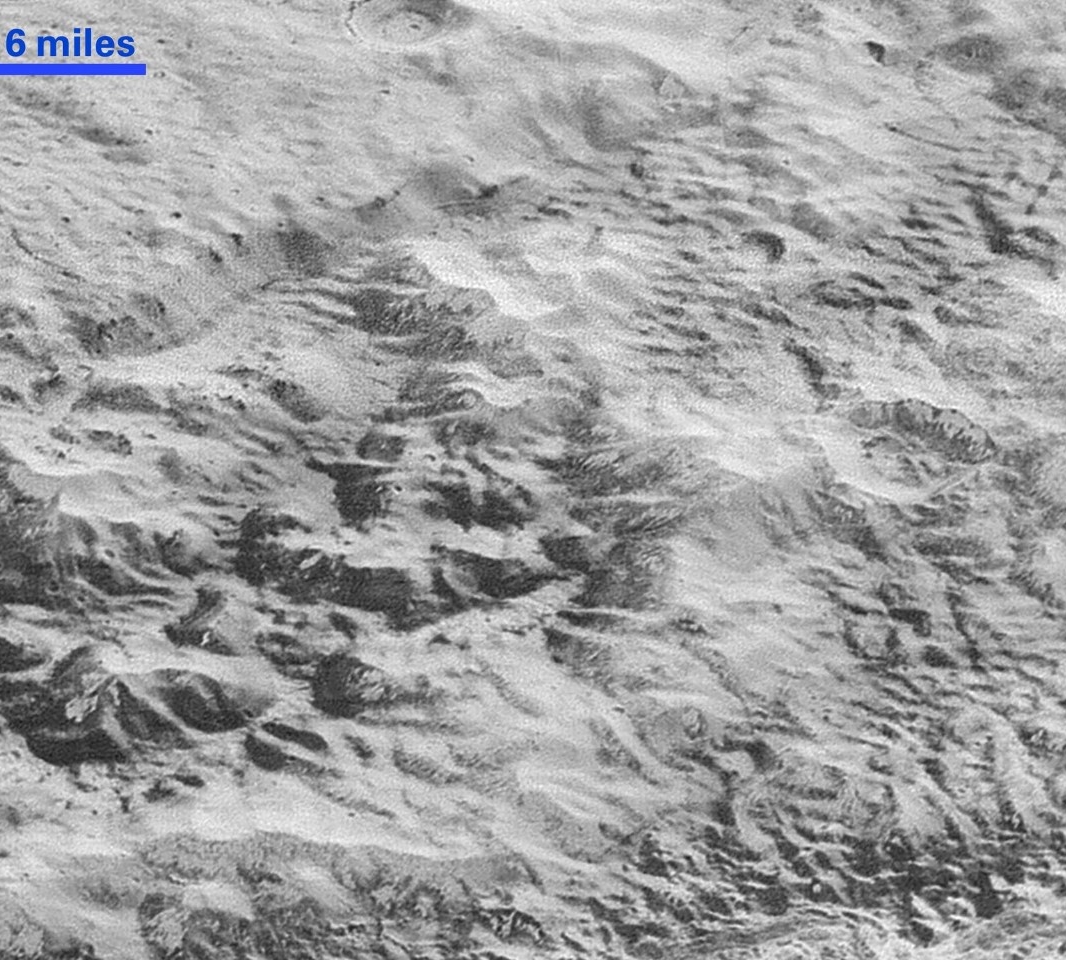

New Horizons captured this image of what scientists call Pluto’s “badlands,” an area of rugged hills fronting a 1-mile-tall cliff. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

Observations continue

Now, New Horizons is flying more than 1 billion miles beyond Pluto in the Kuiper Belt, where it is shedding light on the origins of the universe 4.5 billion years ago. The spacecraft will intercept an asteroid-like object called MU69 in 2019. Stern said his team hopes to learn about its origins, geology and atmosphere.

“It’s a billion miles farther out than Pluto. It’s on the very frontier of human knowledge,” Stern said. “So we can learn about the very origins of our solar system.”

New Horizons will explore the Kuiper Belt through 2021. After that, the spacecraft will continue its deep-space exploration, sending back data and images as one of Earth’s most distant observatories.

“The spacecraft is in almost perfect health. There is really nothing wrong with it. We’re not using any of our backup systems. And all of our backup systems are healthy,” he said. “So there’s a long and bright future for New Horizons into 2030.”

Next frontier

UC’s Hanson said the scientific achievement that New Horizons represents can’t be overstated. The mission was fraught with urgency to take advantage of the gravitational assists of other planets and reach Pluto during its comparatively short summer before its atmosphere froze and settled back onto the surface on its long winter trip around the sun.

And just like the fictional kingdom of Westeros featured in HBO’s “Game of Thrones,” Pluto’s seasons take human generations during its elliptical 248-year orbit of the sun. The next chance scientists will have to observe Pluto’s atmosphere will be about two centuries from now. Pluto will be closest to the sun again in 2237.

“They couldn’t wait. There definitely was a time crunch there,” Hanson said.

By launching when it did, New Horizons was able to capture stunning images of Pluto’s ice-blue atmosphere. Hanson credited the dedication of Stern and his team for the mission’s success.

“He’s super-enthusiastic and he always has been. You have to have that passion and determination and willingness to take risks,” she said.

And it all started with a graduate student with the courage to ask why not?

“My dream was to explore the farthest planet ever explored,” Stern said. “Follow your dreams. Follow your heart. Stick with it. Do the things that you love and you can accomplish amazing things. That’s the lesson.”

New Horizons captured the blue haze of Pluto's methane atmosphere during the spacecraft's 2015 flyby. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

Quelle: University of Cincinnati

---

Update: 9.09.2017

.

New Horizons Files Flight Plan for 2019 Flyby

Artist's concept of the New Horizons spacecraft flying by a possible binary 2014 MU69 on Jan. 1, 2019. Early observations of MU69 hint at the Kuiper Belt object being either a binary orbiting pair or a contact (stuck together) pair of nearly like-sized bodies with diameters near 20 and 18 kilometers (12 and 11 miles).

NASA’s New Horizons mission has set the distance for its New Year’s Day 2019 flyby of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69, aiming to come three times closer to MU69 than it famously flew past Pluto in 2015.

That milestone will mark the farthest planetary encounter in history – some one billion miles (1.5 billion kilometers) beyond Pluto and more than four billion miles (6.5 billion kilometers) from Earth. If all goes as planned, New Horizons will come to within just 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) of MU69 at closest approach, peering down on it from celestial north. The alternate plan, to be employed in certain contingency situations such as the discovery of debris near MU69, would take New Horizons within 6,000 miles (10,000 kilometers) — still closer than the 7,800-mile (12,500-kilometer) flyby distance to Pluto.

“I couldn’t be more excited about this encore performance from New Horizons,” said NASA Planetary Science Director Jim Green at Headquarters in Washington. “This mission keeps pushing the limits of what’s possible, and I’m looking forward to the images and data of the most distant object any spacecraft has ever explored.”

If the closer approach is executed, the highest-resolution camera on New Horizons, the telescopic Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) should be able to spot details as small as 230 feet (70 meters) across, for example, compared to nearly 600 feet (183 meters) on Pluto.

“We’re planning to fly closer to MU69 than Pluto to get even higher resolution imagery and other datasets,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, Colorado. “The science should be spectacular.”

The team weighed numerous factors in making its choice, said science team member and flyby planning lead John Spencer, also of SwRI. “The considerations included what is known about MU69’s size, shape and the likelihood of hazards near it, the challenges of navigating close to MU69 while obtaining sharp and well-exposed images, and other spacecraft resources and capabilities,” he said.

Using all seven onboard science instruments, New Horizons will obtain extensive geological, geophysical, compositional, and other data on MU69; it will also search for an atmosphere and moons.

“Reaching 2014 MU69, and seeing it as an actual new world, will be another historic exploration achievement,” said Helene Winters, the New Horizons project manager from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “We are truly going where no one has gone before. Our whole team is excited about the challenges and opportunities of a voyage to this faraway frontier.”

Quelle: NASA

---

Update: 7.11.2017

.

Help Nickname New Horizons' Next Flyby Target

Artist's concept of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft flying by a possible binary 2014 MU69 on Jan. 1, 2019. Early observations of MU69 hint at the Kuiper Belt object being either a binary orbiting pair or a contact (stuck together) pair of nearly like-sized bodies with diameters near 20 and 18 kilometers (12 and 11 miles).

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Carlos Hernandez

NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt is looking for your ideas on what to informally name its next flyby destination, a billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) past Pluto.

On New Year's Day 2019, the New Horizons spacecraft will fly past a small, frozen world in the Kuiper Belt, at the outer edge of our solar system. The target Kuiper Belt object (KBO) currently goes by the official designation "(486958) 2014 MU69." NASA and the New Horizons team are asking the public for help in giving "MU69" a nickname to use for this exploration target.

"New Horizons made history two years ago with the first close-up look at Pluto, and is now on course for the farthest planetary encounter in the history of spaceflight," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. "We're pleased to bring the public along on this exciting mission of discovery."

After the flyby, NASA and the New Horizons project plan to choose a formal name to submit to the International Astronomical Union, based in part on whether MU69 is found to be a single body, a binary pair, or perhaps a system of multiple objects. The chosen nickname will be used in the interim.

"New Horizons has always been about pure exploration, shedding light on new worlds like we've never seen before," said Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. "Our close encounter with MU69 adds another chapter to this mission's remarkable story. We're excited for the public to help us pick a nickname for our target that captures the excitement of the flyby and awe and inspiration of exploring this new and record-distant body in space."

The naming campaign is hosted by the SETI Institute of Mountain View, California, and led by Mark Showalter, an institute fellow and member of the New Horizons science team. The website includes names currently under consideration; site visitors can vote for their favorites or nominate names they think should be added to the ballot. "The campaign is open to everyone," Showalter said. "We are hoping that somebody out there proposes the perfect, inspiring name for MU69."

The campaign will close at 3 p.m. EST/noon PST on Dec. 1. NASA and the New Horizons team will review the top vote-getters and announce their selection in early January.

Telescopic observations of MU69, which is more than 4 billion miles (6.5 billion kilometers) from Earth, hint at the Kuiper Belt object being either a binary orbiting pair or a contact (stuck together) pair of nearly like-sized bodies – meaning the team might actually need two or more temporary tags for its target.

"Many Kuiper Belt Objects have had informal names at first, before a formal name was proposed. After the flyby, once we know a lot more about this intriguing world, we and NASA will work with the International Astronomical Union to assign a formal name to MU69," Showalter said. "Until then, we're excited to bring people into the mission and share in what will be an amazing flyby on New Year's Eve and New Year's Day, 2019!"

To submit your suggested names and to vote for your favorites, go to: http://frontierworlds.seti.org

Quelle: NASA

---

Update: 5.12.2017

.

NASA Extends Campaign to Nickname New Horizons' Next Target

NASA is extending the campaign to find a temporary tag for the next flyby target of its New Horizons mission, giving the public until midnight Eastern Time on Dec. 6 to continue to help select a nickname for the Kuiper Belt object known as 2014 MU69.

On New Year's Day 2019, the New Horizons spacecraft will fly past this small, frozen Kuiper Belt world (or pair of worlds, if MU69 is a binary as scientists suspect) near the outer edge of our planetary system. This Kuiper Belt object (KBO) currently goes by the official designation "(486958) 2014 MU69." But earlier this month, NASA and the New Horizons team asked the public for help in giving "MU69" a nickname to use for this exploration target. The public suggested such a wide range of creative and quality nicknames that the mission team wanted to give web visitors additional time to vote.

The public suggested such a wide range of creative and quality nicknames that the mission team wanted to give web visitors additional time to vote. More than 96,000 votes have been cast and 31,000 names nominated, with participation coming from 118 countries.

The campaign website (http://frontierworlds.seti.org) includes nicknames under consideration; site visitors can vote for their favorites or nominate names they think should be added to the ballot. The campaign will close at midnight EST/9 pm PST on Wednesday, Dec. 6. NASA and the New Horizons team will review the top vote-getters and announce a selection in early January.

Quelle: NASA