19.07.2017

LISA Pathfinder: Time called on Europe's gravity probe

The European Space Agency (Esa) has turned off one of its most successful ever missions.

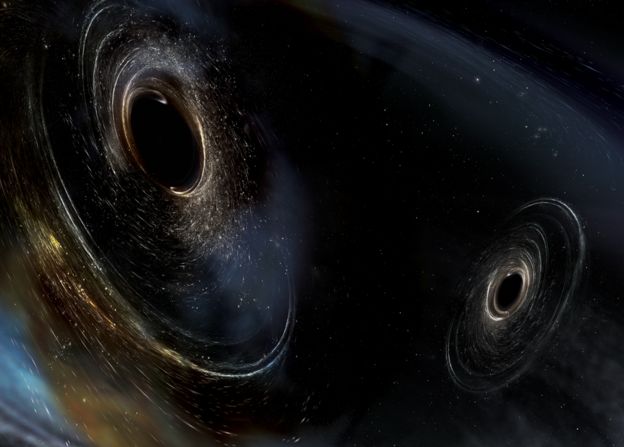

LISA Pathfinder was sent into orbit in 2015 to prove key technologies that could be used on some future project to detect gravitational waves - the ripples that disturb space-time whenever black holes collide.

The satellite spectacularly surpassed the objectives set for it.

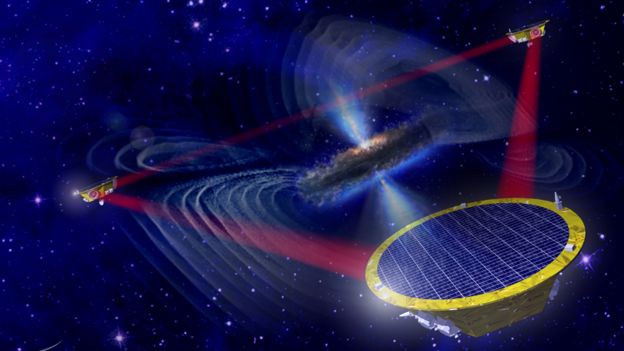

And that success led directly to the selection in June of the LISA mission.

This billion-euro venture, which is envisaged as a trio of satellites, is expected to launch between 2030 and 2034.

It will incorporate many of Pathfinder's systems, including its all-important laser interferometer instrumentation that we now know has the means necessary to catch gravitational waves (GW) in space.

"LISA Pathfinder has shown that LISA is feasible at full sensitivity, more than we could hope for," said principal investigator Stefano Vitale.

"I think it has been a stepping stone for GW astronomy, and an incredibly rewarding experience for all the team involved. Thank you, and stay tuned on LISA!" he told BBC News.

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA

Prof Vitale was invited to send the final "kill commands" to Pathfinder, which has been conducting its measurement demonstration 1.5 million km from Earth in the sunward direction.

The commands, despatched from Esa's mission control centre in Darmstadt, Germany, tricked Pathfinder to reboot itself on to software that had already been corrupted.

It meant the gravity probe was locked down, unable to run its subsystems including its transmitter.

"The only way you could recover the spacecraft would be to go up there and attach an umbilical and restart from another computer," explained Pathfinder's spacecraft operations manager, Ian Harrison.

The kill procedure, more properly known as "passivating" the satellite, ensures there is no hazard to future missions through a collision or interference of radio communications.

The Darmstadt team in April had already fired the thrusters on Pathfinder to move it away from its station - a popular location for many Sun-studying missions.

It should now drift harmlessly around our star.

"There's a very, very small chance it could return to the Earth-Moon system; it's so remote but you can't actually say it's zero," said Ian Harrison.

"The mission analysis actually looked at the planetary positions 500 years into the future."

Gravitational waves - Ripples in the fabric of space-time

Image copyrightIGO/CALTECH/MIT/SONOMA STATE

Image copyrightIGO/CALTECH/MIT/SONOMA STATE

Gravitational waves are the big thing in science right now.

Ground-based laboratories in the US have recently begun detecting them from coalescing objects that are 20-30 times the mass of our Sun.

But by sending an observatory into space, scientists would expect to discover sources that are millions of times bigger still, and to sense their activity all the way out to the edge of the observable Universe.

It should significantly advance our understanding of gravity and how it works; and perhaps even highlight some chinks in Einstein's so-far flawless equations.

LISA will detect gravitational waves by bouncing laser light between three spacecraft flying in a triangle formation, where the sides of the triangle are 2.5 million km long. The light beams will be measuring the precise positions of small, free-floating blocks inside the satellites.

When gravitational waves pass through the triangle, the distance between blocks of the different spacecraft should change by tiny amounts - just fractions of the width of an atom.

Laser science: Lisa Pathfinder's technology demonstration

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA

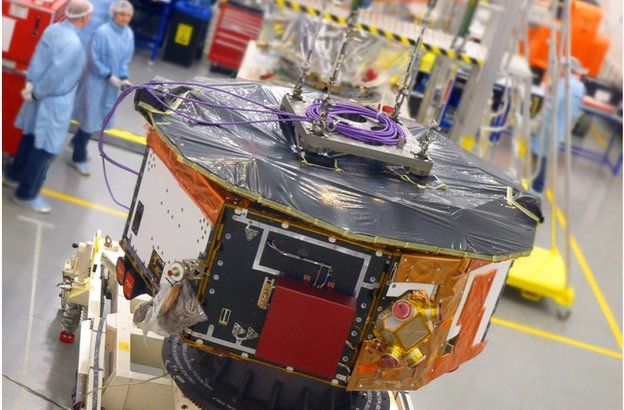

- Lisa Pathfinder carried a laser interferometer to measure the behaviour of two free-falling blocks made from a platinum-gold alloy

- Placed 38cm apart, these "test masses" were held inside cages that were engineered to insulate them against all disturbing forces

- Whenever this super-quiet environment is maintained, the falling blocks should follow a "straight line" that is defined only by gravity

- And it is under such conditions that a passing gravitational wave could be noticed by ever so slightly changing the blocks' separation

- Lisa Pathfinder demonstrated sub-femtometre sensitivity, but the satellite itself could not make a detection of the famous ripples

- For that, a space-borne observatory would need to reproduce the same performance but with blocks positioned 2.5 million km apart

- Lisa Pathfinder, however, proved the measurement principle and paved the way for the LISA mission's selection by Esa nations

LISA Pathfinder's laser and gold-block monitoring system was shrunk down to fit inside a single satellite. As such, it could not itself detect gravitational waves, but the exquisite sensitivity of the instrumentation demonstrated that the metrology principles were sound.

"LISA Pathfinder did more than we ever asked for," said Paul McNamara, Esa's Pathfinder project scientist.

"It met its requirements on day one, the day we switched on its science. But we then met and surpassed the requirements of LISA. So, it's been a phenomenal mission. It's sad to turn Pathfinder off but at some point we have to look to the future," he told BBC News.

Image copyrightAIRBUS DS

Image copyrightAIRBUS DS

Quelle: BBC

---

Update: 23.07.2017

.

Gute Nacht, LISA Pathfinder!

LISA Pathfinder nach einer erfolgreichen Mission, die alle Erwartungen übertraf, am Abend des 18. Juli wie geplant abgeschaltet

19. Juli 2017

Ein einzigartiger Moment

„Als wir gestern Abend das letzte Mal Kontakt mit LISA Pathfinder hatten und uns vom Satelliten verabschiedeten, war das ein einzigartiger und emotionaler Moment“, sagt Prof. Karsten Danzmann, Direktor am Max-Planck-Institut für Gravitationsphysik, Direktor des Instituts für Gravitationsphysik der Leibniz Universität Hannover und Co-PI der LISA-Pathfinder-Mission. „Nach jahrelanger Planung und dem Start des Satelliten im Dezember 2015 haben wir seit Anfang 2016 viele Tage und Nächte damit verbracht, mit LISA Pathfinder den Weg für die Zukunft der Gravitationswellen-Astronomie zu ebnen.“

LISA Pathfinder hat mit seinen Messungen, die die Erwartungen aller beteiligten Wissenschaftler übertrafen, gezeigt, dass die erforderliche Technologie für die geplante LISA-Mission bestens funktioniert. Nun arbeitet das internationale Forschungsteam unter Federführung von Hannoveraner Forschenden mit Hochdruck daran, das größte Gravitationswellen-Observatorium aller Zeiten zu realisieren.

Die Zukunft der Gravitationswellen-Astronomie mit LISA

LISA soll im Jahr 2034 als Mission der Europäischen Weltraumorganisation (ESA) ins All starten. US-Forschende prüfen derzeit wie die NASA sich an der Mission beteiligen kann. LISA wird aus drei Satelliten bestehen, die mit Lasern ein gleichseitiges Dreieck mit 2,5 Millionen Kilometern Kantenlänge aufspannen. Durch den Formationsflug im All laufende Gravitationswellen verändern diese Abstände um Billionstel Meter.

LISA wird niederfrequente Gravitationswellen messen. Diese entstehen bei Ereignissen wie verschmelzenden extrem massereichen Schwarzen Löchern mit Millionen oder Milliarden Sonnenmassen in Galaxienzentren, Millionen von Doppelsternen in unserer Galaxie oder exotischen Quellen wie kosmischen Strings.

„Nach dem Ende der Pathfinder-Mission können wir unsere Arbeit mit vollem Elan an LISA fortsetzen. Mit LISA werden wir die Verschmelzungen extrem massereicher Schwarzer Löcher aus dem gesamten Universum belauschen und ihre Eigenschaften erfassen“, so Danzmann. „Damit ergänzen wir die Messungen irdischer Detektoren wie GEO600, LIGO und Virgo und vervollständigen unser lückenhaftes Bild von der dunklen Seite des Universums.“

Guter Satellit, du gehst so stille…

Die Bordsysteme von LISA Pathfinder schalteten sich nach Empfang der Signale aus dem Europäischen Weltraumkontrollzentrum ESOC am 18. Juli 2017 kurz nach 20:00 Uhr MESZ ab. Damit hält der Satellit Funkstille ein und sendet und empfängt keine weiteren Signale im Radiobereich. Die meisten Komponenten des Weltraumlabors sind ebenfalls abgeschaltet. Bereits im April sorgte ein Bahnmanöver dafür, dass der Satellit in eine sichere Parkumlaufbahn um die Sonne eintrat, die ihn für mehr als 100 Jahre von der Erde fern hält.

Quelle: MAX-PLANCK-GESELLSCHAFT, MÜNCHEN