25.05.2017

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA

The crashed European spacecraft Schiaparelli was ill-prepared for its attempt at landing on the surface of Mars.

That's the conclusion of an inquiry into the failure on 16 October 2016.

The report outlines failings during the development process and makes several recommendations ahead of an attempt to land a rover on Mars in 2020.

That mission will require more testing, improvements to software and more outside oversight of design choices.

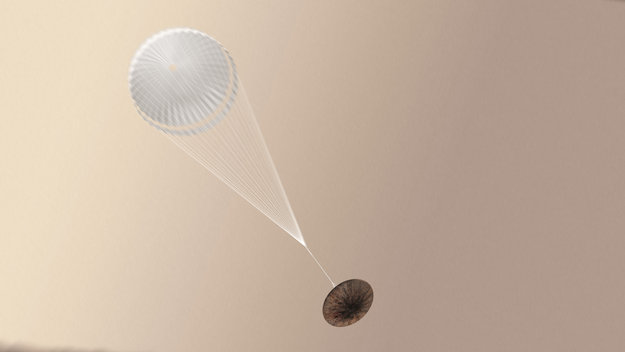

The Schiaparelli module was intended to test the European Space Agency's (Esa) capability for atmospheric entry, descent and - finally - landing on the surface of Mars.

The report confirms some details already released in the preliminary findings. For example, during the descent - and after the parachute had been deployed - a component called the inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensed rotational accelerations in the probe that were larger than expected.

This led to the IMU data becoming "saturated". When this information was integrated by the onboard guidance, navigation and control (GNC) software, the probe erroneously updated where it thought it was in the descent.

The mistaken measurement was propagated forward, and at one point the GNC software calculated a negative altitude for the probe - it thought that Schiaparelli was several metres below the surface of Mars, even though it was still falling.

The descent thrusters turned off and the test module was destroyed as it slammed into the ground in Mars' Meridiani Plain at a velocity of about 150 m/s. But the authors believe the craft could still have landed safely after the wrong handling of the IMU data if other checks and balances had been in place.

The report rules out a fault with the IMU itself and suggests a number of other root causes leading to the failure. These include:

- insufficient computer modelling of the parachute dynamics

- inadequate handling of IMU data by the guidance software

- an inadequate approach by team members towards detecting faults

- problems with the management of subcontractors

In order to ensure that lessons are learned before a joint Esa-Russian Space Agency (Roscosmos) rover is sent to land on Mars in 2020, the inquiry panel made several recommendations.

The report authors catalogue a series of necessary upgrades to onboard software, as well as suggesting improvements to the modelling of parachute dynamics.

They also recommended a more stringent approach - including better quality control - during the procurement of equipment from suppliers.

Crucially, the inquiry also recommends greater outside oversight of the design process for the upcoming rover mission by partner organisations with specific competencies.

These suggested partners include Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) - which has already overseen the successful landing of several robotic missions on Mars.

Quelle: BBC

+++

SCHIAPARELLI LANDING INVESTIGATION COMPLETED

The inquiry into the crash-landing of the ExoMars Schiaparelli module has concluded that conflicting information in the onboard computer caused the descent sequence to end prematurely.

The Schiaparelli entry, descent and landing demonstrator module separated from its mothership, the Trace Gas Orbiter, as planned on 16 October last year, and coasted towards Mars for three days.

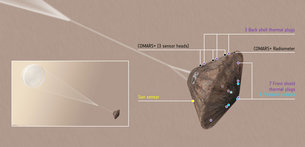

Much of the six-minute descent on 19 October went as expected: the module entered the atmosphere correctly, with the heatshield protecting it at supersonic speeds. Sensors on the front and back shields collected useful scientific and engineering data on the atmosphere and heatshield.

Telemetry from Schiaparelli was relayed to the main craft, which was entering orbit around the Red Planet at the same time – the first time this had been achieved in Mars exploration. This realtime transmission proved invaluable in reconstructing the unfolding chain of events.

At the same time as the orbiter recorded Schiaparelli’s transmissions, ESA’s Mars Express orbiter also monitored the lander’s carrier signal, as did the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope in India.

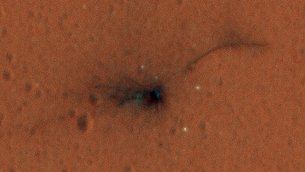

In the days and weeks afterwards, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter took a number of imagesidentifying the module, the front shield, and the parachute still connected with the backshield, on Mars, very close to the targeted landing site.

The images suggested that these pieces of hardware had separated from the module as expected, although the arrival of Schiaparelli had clearly been at a high speed, with debris strewn around the impact site.

The independent external inquiry, chaired by ESA’s Inspector General, has now been completed.

It identifies the circumstances and the root causes, and makes general recommendations to avoid such defects and weaknesses in the future.

Around three minutes after atmospheric entry the parachute deployed, but the module experienced unexpected high rotation rates. This resulted in a brief ‘saturation’ – where the expected measurement range is exceeded – of the Inertial Measurement Unit, which measures the lander’s rotation rate.

The saturation resulted in a large attitude estimation error by the guidance, navigation and control system software. The incorrect attitude estimate, when combined with the later radar measurements, resulted in the computer calculating that it was below ground level.

This resulted in the early release of the parachute and back-shell, a brief firing of the thrusters for only 3 sec instead of 30 sec, and the activation of the on-ground system as if Schiaparelli had landed. The surface science package returned one housekeeping data packet before the signal was lost.

In reality, the module was in free-fall from an altitude of about 3.7 km, resulting in an estimated impact speed of 540 km/h.

The Schiaparelli Inquiry Board report noted that the module was very close to landing successfully at the planned location and that a very important part of the demonstration objectives were achieved. The flight results revealed required software upgrades, and will help improve computer models of parachute behaviour.

“The realtime relay of data during the descent was crucial to provide this in-depth analysis of Schiaparelli’s fate,” says David Parker, ESA’s Director of Human Spaceflight and Robotic Exploration.

“We are extremely grateful to the teams of hard-working scientists and engineers who provided the scientific instruments and prepared the investigations on Schiaparelli, and deeply regret that the results were curtailed by the untimely end of the mission.

“There were clearly a number of areas that should have been given more attention in the preparation, validation and verification of the entry, descent and landing system.

“We will take the lessons learned with us as we continue to prepare for the ExoMars 2020 rover and surface platform mission. Landing on Mars is an unforgiving challenge but one that we must meet to achieve our ultimate goals.”

“Interestingly, had the saturation not occurred and the final stages of landing had been successful, we probably would not have identified the other weak spots that contributed to the mishap,” notes Jan Woerner, ESA's Director General. “As a direct result of this inquiry we have discovered the areas that require particular attention that will benefit the 2020 mission.”

ExoMars 2020 has since passed an important review confirming it is on track to meet the launch window. Having been fully briefed on the status of the project, ESA Member States at the Human Spaceflight, Microgravity and Exploration Programme Board reconfirmed their commitment to the mission, which includes the first Mars rover dedicated to drilling below the surface to search for evidence of life on the Red Planet.

Meanwhile the Trace Gas Orbiter has begun its year-long aerobraking in the fringes of the atmosphere that will deliver it to its science orbit in early 2018. The spacecraft has already shown its scientific instruments are ready for work in two observing opportunities in November and March.

In addition to its main goal of analysing the atmosphere for gases that may be related to biological or geological activity, the orbiter will also act as a relay for the 2020 rover and surface platform.

The ExoMars programme is a joint endeavour between ESA and Roscosmos.

Quelle: ESA