.

23.01.2017

Airbus ready to ship Aeolus for final testing ahead of launch

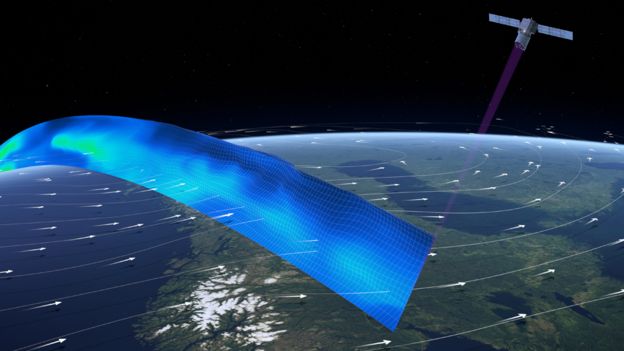

ESA’s wind sensing spacecraft Aeolus ready to leave Stevenage (UK) for final testing

Aeolus will measure global wind speeds in horizontal slices up to 30 km above the Earth’s surface and improve the performance of numerical weather forecasts

Aeolus will bring improvement for climate research and modelling

[Stevenage, 20/01/2017] - Aeolus, the European Space Agency’s wind sensing satellite, is leaving Stevenage, UK, in the next few days on the first part of its journey to space. It will be shipped to Toulouse, France, for final testing before it travels to French Guiana towards the end of the year ready for launch on a Vega launcher.

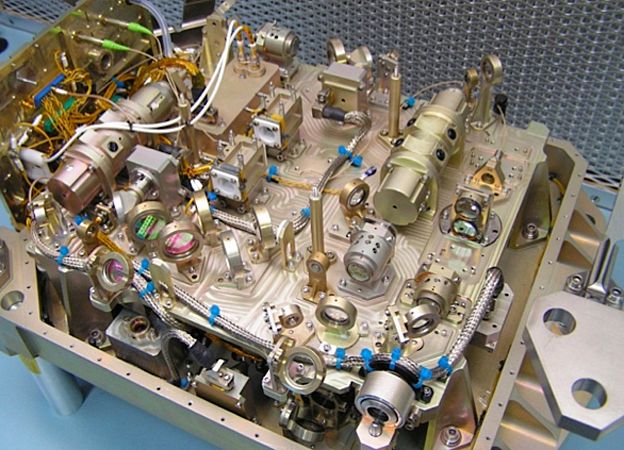

The 1.7-tonne spacecraft, primed by Airbus Defence and Space, features the LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) instrument called Aladin, which uses the Doppler effect to determine the wind speed at varying altitudes.

Aladin fires a powerful ultraviolet laser pulse down through the atmosphere and collects backscattered light, using a large 1.5m diameter telescope, which is then analysed on-board by highly sensitive receivers to determine the Doppler shift of the signal from layers at different heights in the atmosphere.

The data from Aeolus will provide reliable wind-profile data on a global scale and is needed by meteorologists to further improve the accuracy of weather forecasts.

Andy Stroomer, Head of Earth Observation, Navigation and Science in the UK for Airbus said: “With the shipment of Aeolus we reached a key project milestone and we now look forward to launching Aeolus as the forerunner of an operational system that will contribute significantly to improving weather forecasting.”

Beth Greenaway, Head of Earth Observation at the UK Space Agency, said: “It is great to see the Aeolus nearing completion. This is a tangible result of the UK contribution to the ESA EO Envelope programme over many years and is the latest in the Earth Explorer series. These observations will advance our understanding of tropical dynamics and processes relevant to climate variability. Accurate wind forecasts are also vital for commercial undertakings such as farming, fishing, construction and transport. Following the successful ESA Ministerial in December, where the UK allocated more than €1.4 billion over the next five years to European Space Agency programmes, we are looking at taking leading science and industrial roles in many future missions too.”

The spacecraft is leaving Stevenage on 29th January and will make its way by road to Toulouse (Intespace) in a special convoy. Testing will involve simulation of the Vega launch environment using special vibration and acoustic facilities. Following this the spacecraft will move on to specialist facilities at CSL in Liege, Belgium where it will undergo thermal vacuum tests to simulate the extremes of the space environment together with full performance testing of the instrument system.

Aeolus will fly in a 320 km orbit and have a lifetime of three years.

Quelle: Airbus Defence and Space

---

Update: 10.06.2018

.

Airbus-built Aeolus wind sensor satellite ready for shipment

First ever satellite able to perform global wind component profile observation

ESA’s Aeolus will provide measurements on a daily basis in near real-time to improve the accuracy of weather forecasts

Aeolus, the European Space Agency’s wind sensing satellite, is now ready for its upcoming launch. It will be shipped across the Atlantic on the Airbus vessel “Ciudad de Cádiz" to Kourou, French Guiana, where a Vega launcher will send it to orbit on 21 August. The instrument is so sensitive that it could be damaged by a sudden loss of pressure. For this reason, air transportation has to be avoided and for the first time Airbus will transport one of its satellites on-board its own vessel.

The 1.33-tonne spacecraft, primed by Airbus, features the first ever space-borne LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) instrument called Aladin, which uses the Doppler effect to determine the wind speed at varying altitudes.

Aladin fires a powerful ultraviolet laser pulse down through the atmosphere and collects backscattered light, using a large 1.5m diameter telescope, which is then analysed on-board by highly sensitive receivers to determine the Doppler shift of the signal from layers at different heights in the atmosphere.

“Aeolus is a world first with break-through technology that will make a huge contribution to weather forecasting on a global scale. Pioneering a LIDAR instrument in Space is quite a challenge – but a great example of what Europeans can achieve when we work together!”, said Nicolas Chamussy, Head of Space Systems at Airbus.

The data from Aeolus will provide reliable wind-profile data on a global scale and is needed by meteorologists to further improve the accuracy of weather forecasts and by climatologists to better understand the global dynamics of Earth’s atmosphere.

Aeolus will orbit the Earth 15 times a day with data delivery to users within 120 minutes of the oldest measurement in each orbit. The orbit repeat cycle is 7 days (every 111 orbits) and the spacecraft will fly in a 320 km orbit for three years.

Quelle: Airbus

+++

Aeolus: Wind satellite weathers technical storm

They say there is no gain without pain, but when the European Space Agency (Esa) set out in 2002 to develop its Aeolus satellite, no-one could have imagined the grief the project would bring.

Designed to make the first 3D maps of winds across the entire Earth, the mission missed deadline after deadline as engineers struggled to get its key technology - an ultraviolet laser system - working for long enough to make the venture worth flying.

But now, 16 years on, the Aeolus satellite is finished and ready to ship to the launch pad. And far from being snuck out the back door at night in embarrassment at the huge delay, the spacecraft will be mated to its launch rocket with something of a fanfare.

Esa is taking pride in the fact that it overcame a major technical challenge.

"Many times I remember people saying, 'there's just no point in continuing because it is simply not possible to build a UV laser for space'. But this is the DNA of Esa - we do the difficult things and we don't give up," said the agency's Earth observation director, Dr Josef Aschbacher.

It helped of course that Aeolus promises data that many experts still believe will be transformative.

From its vantage point some 320km above the planet, the laser will track the movement of molecules and tiny particles to get a handle on the direction and speed of the wind.

How to measure the wind from space

Image copyrightESA

Image copyrightESA- Aeolus will fire a laser through the atmosphere and measure the return signal

- The light will scatter back off air molecules and particles moving in the wind

- Meteorologists will adjust their numerical models to match this information

- The biggest benefits should be in medium-range forecasts - a few days hence

- Aeolus should pave the way for operational weather satellites with lasers

Currently, we measure the dynamics of the atmosphere using an eclectic mix of tools - everything from whirling anemometers to other types of satellite that judge wind behaviour from the choppiness of seawater. But these are all limited indications, telling us what is happening in particular places or at particular heights.

Aeolus, on the other hand, will attempt to build a truly global view of what the winds are doing on Earth, from the surface of the planet all the way up through the troposphere and into the stratosphere (from 0km to 30km).

"The lack of wind profile observations is one of the most important gaps to fill in order to improve numerical weather prediction," Dr Florence Rabier, the DG at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), told BBC News.

"The Aladin Doppler wind lidar instrument onboard Aeolus will be the first satellite instrument that provides wind profiles from space.

"We have very high expectations regarding the quality of the Aeolus wind profile data, and we are anticipating forecast quality to increase by 2-4% in the extra-tropics and up to 15% in the tropics. Aeolus is paving the way for significant improvements in weather forecasting".

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

There is an example that meteorologists quote from March 2014 - storminess that led to flooding in northern Europe.

When they did the post-event analysis to figure out why no-one had seen it coming, the conclusion was that inaccurate wind data six days previously had been used in the models. Dr Alain Dabas from MeteoFrance explained: "The error was in the central Pacific at an altitude of about 11km. There was a mistake in the initial winds given to the models and that propagated to Europe.

"The question now is would Aeolus have solved this problem? Probably, yes."

It goes without saying that knowing what the wind is going to do reaches beyond just the nightly weather forecast on TV. How it blows affects the distribution and transport of pollutants, and how quickly bad air in a hazy city, say, can be cleared away.

Then there are the requirements of safety to consider - think sailors at sea, or construction on high-rise buildings. And don't forget the sectors whose whole reason to exist rests on the wind.

"For instance, the wind energy industry," said Dr Anne Grete Straume, Esa's Aeolus mission scientist. "They're exploiting the winds and they need to know how much energy they can produce at any point in time. For that they need very accurate forecasts and we hope that our mission can help them with their management."

But all this depends on the UV laser doing its job. The engineers are very confident now that it can. They recently put the finished Aeolus satellite in a space chamber for six months to simulate the conditions of being in orbit. The whole system passed with flying colours.

It is worth recalling some of the past frustrations. The first problem was in finding diodes to generate laser light with a long enough lifetime. When those were identified, the mission looked in great shape until engineers discovered their design wouldn't actually operate in a vacuum - a significant barrier for a space mission.

Tests revealed that in the absence of air, the laser was degrading its own optics; as the high-energy light hit the lenses and mirrors, it would blacken them.

Companies across Europe were pushed to develop new coatings for the various elements. The key breakthrough, however, was to introduce a small amount of oxygen to the instrument to prevent surfaces carbonising.

It's a tiny puff of gas - 40 pascals' worth; the same pressure you might expect to develop from the presence of a photosynthesising plant. But it is sufficient to oxidise contaminants and remove them.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

"When we started, the only references we had were classified because these types of lasers are used to represent atomic bombs, and those technologies were totally locked out," said Anders Elfving, Esa's Aeolus project manager.

"The motivation for my team all these years was that there is no alternative, and of course the user community is still so enthusiastic for what we've built.

"We want to see what is invisible - to see the wind in clear skies. And I think active lidars like Aladin are the future - for much more accurate measurements of CO2 and other trace gases in the atmosphere."

The launch of Aeolus on a Vega rocket is currently set for 21 August.