Its surface is hot enough to melt lead and its skies are darkened by toxic clouds of sulphuric acid. Venus is often referred to as Earth’s evil twin, but conditions on the planet were not always so hellish, according to research that suggests it may have been the first place in the solar system to have become habitable.

The study, due to be presented this week at the at the American Astronomical Society Meeting in Pasadena, concludes that at a time when primitive bacteria were emerging on Earth, Venus may have had a balmy climate and vast oceans up to 2,000 metres (6,562 feet) deep.

Michael Way, who led the work at the Nasa Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City, said: “If you lived three billion years ago at a low latitude and low elevation the surface temperatures would not have been that different from that of a place in the tropics on Earth,” he said.

The Venusian skies would have been cloudy with almost continual rain lashing down in some regions, however. “So while you might get nice sunsets you would have mostly overcast skies during the day and precipitation,” Way added.

Crucially, if the calculations are correct the oceans may have remained until 715m years ago - a long enough period of climate stability for microbial life to have plausibly sprung up.

“The oceans of ancient Venus would have had more constant temperatures, and if life begins in the oceans - something which we are not certain of on Earth - then this would be a good starting place,” said Way.

Other planetary scientists agreed that, despite the differing fates of the two planets, early Earth and Venus may have been similar.

Professor Takehiko Satoh, who works on the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Venus Climate Orbiter (“Akatsuki”) mission, said: “Habitable or not, I’m not in a position to answer. Environment-wise, probably Venus once had an ocean and probably the environment of Venus and the Earth might have been similar.”

With an average surface temperature of 462C (864F), Venus is the hottest planet in the solar system today, thanks to its proximity to the sun and its impenetrable carbon dioxide atmosphere, 90 times denser than Earth’s. At some point in the planet’s history this led to a runaway greenhouse effect.

Previous US and Soviet landers sent to Venus have survived only a few hours on the surface before being destroyed.

Way and colleagues simulated the Venusian climate at various time points between 2.9bn and 715m years ago, employing similar models to those used to predict future climate change on Earth. The scientists fed some basic assumptions into the model, including the presence of water, the intensity of the sunlight and how fast Venus was rotating. In this virtual version, 2.9bn years ago Venus had an average surface temperature of 11C (52F) and this only increased to an average of 15C (59F) by 715m years ago, as the sun became more powerful.

More precise measurements of the chemical makeup of Venus’s surface and atmosphere could help establish how much water the planet had in the past, and when this began to disappear.

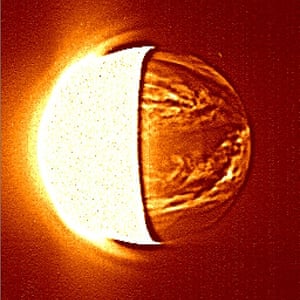

Some of this information may be filled in by the Akatsuki mission, which is observing the Venusian weather systems in unprecedented detail. The spacecraft was supposed to enter orbit about the planet in 2010, but after its main engine blew out, it instead spent five years drifting around the sun like a miniature artificial planet. Last year, scientists used altitude thrusters to redirect it into an orbit, and the mission could yet answer longstanding questions about our planetary neighbour, including whether it has volcanic activity, whether lightning strikes in the sky and why its atmosphere is rotating 60 times faster than the planet itself.

However, searching for traces of ancient microbial life would need a lander, and would be significantly more challenging.

“It would take a great deal of technology development, and money of course, to build the requisite landing craft to survive the surface conditions of present day Venus and to be able to dig into the surface,” said Way. “But if the investments were made it would be possible to search for such signs of life, including chemical traces.”

Details of the study are also published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Quelle: theguardian