28.09.2016

-

LIVING WITH A COMET: A CONSERT TEAM PERSPECTIVE

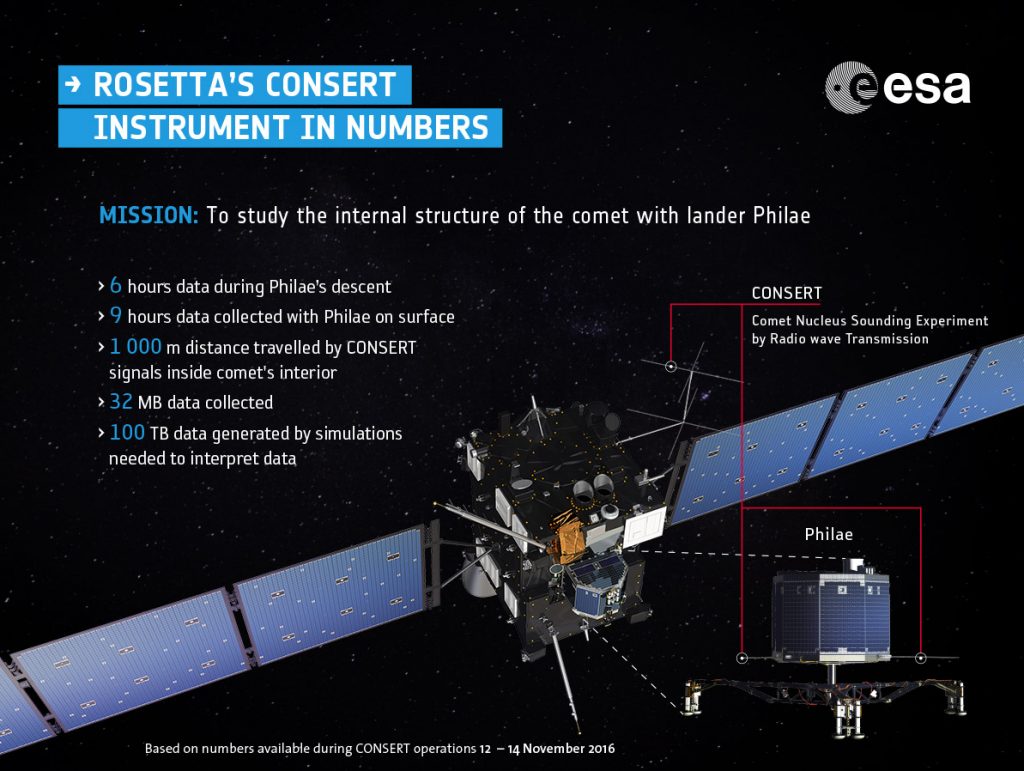

Rosetta and Philae were both equipped with the CONSERT radar experiment in order to bounce radio waves between the two to study the internal structure of the comet. Little did we know that this instrument would play a critical role in locating where the missing lander had bounced to after its unexpected landing on 12 November. Instrument Principal Investigator Wlodek Kofman shares how CONSERT’s modest measurements have yielded big results.

It is good to remember that CONSERT, in the morning of 13 November 2014, provided the first estimation of where Philae had bounced to the previous day, based on the data collected overnight from 12 to 13 November. After that the Rosetta project requested to add three additional operations of CONSERT in order to perform the triangulation and improve the localization. The triangulation measurements were done in the special ‘adapted operation’ mode that was designed and implement in a very short time, due to the unexpected landing conditions.

During the descent, CONSERT operated for about 6 hours during the descent, until about 50 minutes before the planned touchdown. The measured distance between Rosetta and Philae corresponded to the planned one, which meant that during the descent we knew that everything went smoothly. The CNES team used these data for the reconstruction of the lander descent trajectory.

Although the total amount of data collected – 32 Mbytes – is rather small, we need to run 3D computer simulations with ‘heavy’ comet shape models that generate 100 TBytes of temporary data in about 1 million total CPU-core computing time in order to interpret these measurements.

In spite of Philae’s CONSERT antenna ending up in an unfavourable configuration when it finally came to rest in Abydos, we still made successful operations, and made some interesting scientific discoveries. For example, the value of the dielectric constant derived from CONSERT data is very low and typical of an extremely porous medium. We could also infer that the upper part of the small lobe is fairly homogeneous, down to a scale of several metres.

Thanks to CONSERT data and improved comet shape models that have been produced since Philae’s landing by the OSIRIS team, we could also refine our estimate of where Philae could be. Now,Philae has been finally imaged on the surface and confirmed to be within the boundaries of our original prediction. Knowing the exact position and close environment of the lander, we will be able to start interpreting the amplitude of our signal data in addition to the radiowave pure travel time analysis.

CONSERT is an innovative instrument built especially for the Rosetta mission, to study the cometary interior. After the successful study of the interior of the comet, CONSERT-like radars are now being proposed for future small bodies missions such as AIM.

This post is part of a series that looks behind the scenes of the instrument teams to find out what it was really like "living with a comet" for two years.

---

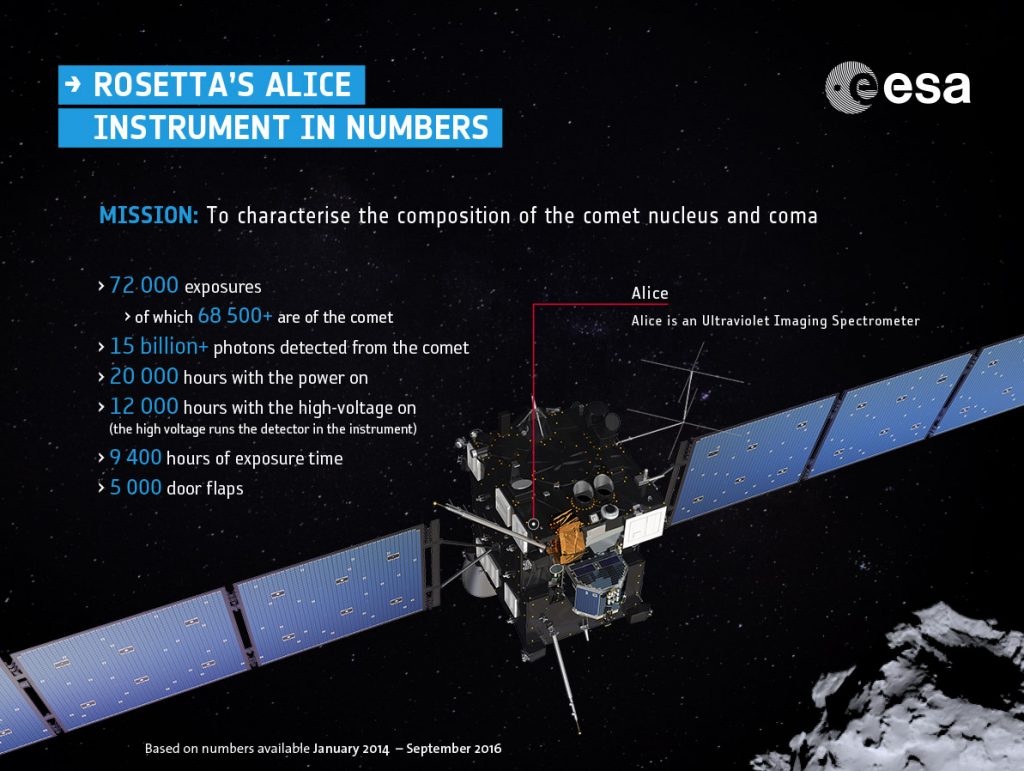

LIVING WITH A COMET: AN ALICE TEAM PERSPECTIVE

Rosetta’s ‘Alice’ instrument – which is the only Rosetta instrument that isn’t an acronym, it is simply a name that the instrument’s principal investigator, Alan Stern, likes – was the first in a line of ultraviolet spectrographs that have also flown on NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance orbiter, New Horizons and JUNO. It has also been with some Alice team members for their entire lives. With inputs from Alan Stern, Joel Parker, Mike A’Hearn, and John Noonan.

John Noonan is the youngest Alice team member – he was just 10 when Rosetta launched. “Rosetta really got started in the same year I was born, and being able to work on a mission that is the same age as me has been incredibly humbling,” he says. “Working on Rosetta while attending college showed me exactly what I would be getting myself into by continuing to study astrophysics, and has been a driving force in getting me to where I am today.”

Joel Parker, Alice’s deputy principal investigator (PI), adds: “My son was born when I started working on Rosetta and now he is a Junior in college; he grew up with Rosetta all his life.”

To illustrate just how long Rosetta’s mission has been compared with other missions, Mike A’Hearn, a co-investigator on the Alice science team and PI of NASA’s Deep Impact comet mission says: “the concept of our Deep Impact comet mission was first invented after we wrote the proposal for Rosetta-Alice, and yet the Deep Impact prime mission was completed three years before Rosetta even reached its first scientific target, asteroid Steins. This perhaps also highlights the difference between a small PI-led mission with one specific task, and a large mission like Rosetta, with many PI-led instruments with many objectives!”

Rosetta’s Alice was the first of the “Alice” line of ultraviolet spectrographs (UVS). Since then, various Alices have flown to different corners of the Solar System: Pluto (on New Horizons); the Moon (on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter – the UVS is called “LAMP”, the Lyman Alpha Mapping Project); Jupiter (on JUNO, the instrument is simply the UVS), and more are in development for missions to Jupiter (such as ESA’s JUICE mission) and Europa – its legacy will live on.

Rosetta’s Alice certainly set a high standard; some of the team’s top discoveries and accomplishments include:

-the first far-ultraviolet spectra of a comet surface, which found 67P to be very dark, reflecting only a few percent of the ultraviolet light that falls on it, and has a fairly uniform reflectance all over the surface with no large ice patches;

-monitoring the nature of outbursts on the comet, including those electron collisions and suggestion of presence of molecular oxygen;

-studying how some outbursts appear to be gas-dominated and others dust-dominated;

-learning how the Alice detector can be used to measure dust and particle activity around the comet.

Moving instrument parts in space: Alice door flaps

Alice has only a few moving parts. A couple of them can move only once, e.g., the door covering the detector is a spring-loaded door that we opened early in the mission and is stays open forever. But there is only one part that moves more than once, and that is the "aperture door" that is near the front of the instrument. It usually is closed when Alice is not observing. It protects the inside of the instrument (the sensitive optical surfaces and the high voltage detector) from dust and gas from the comet or the spacecraft thrusters, and also from too-bright objects. So, for example, if the spacecraft will be firing thrusters, we close the door and wait 30 minutes for any residual gas to dissipate before opening the door and turning on the high voltage. If GIADA reported a dust environment that got too high, we could close the door, but the dust never got that intense, as far as Alice is concerned.

It is generally a good idea for space instruments to minimize the number of moving parts because those are at the highest risk of failing or breaking, and you can't send up a handy repairman to fix it when it breaks. So we are careful to monitor the number of times we open/close the door and also occasionally test it to see if it seems to be getting “sticky” or misbehaving in some way that might indicate an impending failure. The door on Alice was rated for at least 10,000 “flaps” (open/close cycles), and that number gives a factor of two buffer relative to ground tests. Rosetta’s Alice had about 5,000 flaps through the course of the mission, but the record-holder is the LAMP UVS instrument on LRO, which so far has made over 80,000 door flaps!

If the Rosetta-Alice door did get stuck, there are various options we could have considered. If it got stuck open, we probably would have left it open; it would have increased risk of contamination, but if we continued to try to close it, there would be the risk that if it did close, it then would be stuck closed. If it got stuck closed, we had a small “failsafe” door that is a open-one-time door below the aperture door that would still have allowed about 10% of the light to get through, so we could still keep doing Alice science, through with reduced sensitivity.

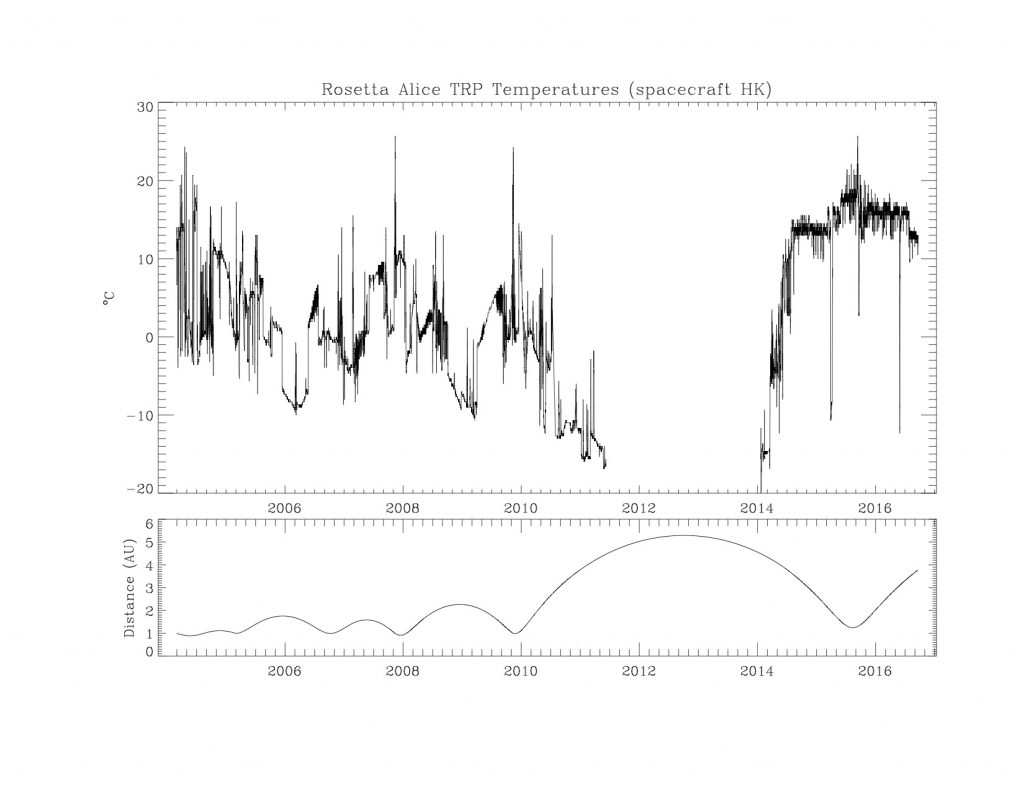

Hot and cold

A spacecraft sensor attached to an external foot of Alice measured the temperature of the instrument throughout the entire mission (Rosetta’s distance from the Sun is indicated along the bottom). The gap in data corresponds to the 31-month period of deep space hibernation when no temperatures were recorded, and we don’t know how cold it got! After hibernation, Alice and the spacecraft started warming up again, and then we adjusted our standard operations to run Alice with the heaters always on, which helped to stabilize the temperature. Sudden spikes in the data are attributed to changes in the spacecraft attitude, depending on whether the side of the spacecraft with Alice on was pointed towards the Sun or away. Image courtesy Joel Parker.

Avoiding "bad dogs"

Joel adds: “Orbital missions keep you busy all the time, trying to simultaneously keep up with planning operations and looking at the stream of resulting data. We always keep in mind that a spacecraft in flight doesn't care when you plan your vacation! And as this was a European mission but I lived in Colorado, if the phone rang at 1:00 at night (9am in Darmstadt), I knew it would be someone from the Mission Operations Centre to report a problem.”

He recalls a few such problems and false alarms: “For example, Alice autonomously shut down when it received data indicating the pressure of the gas around the spacecraft might have increased to levels too high to operate, but as it turned out, the pressure values reported to Alice were incorrect – although in the space business, it is better to be safe than sorry! Another time Alice’s computer mysteriously rebooted – an event that happened only twice during the mission.

“At other times, Alice stopped running exposures because a “too bright object” came into the field of view. The first time that happened, it turned out that it was a bright star and Alice’s internal safety checks correctly “safed” the instrument. As Alice orbited 67P, such bright stars (the Alice team called them “bad dogs”) would frequently cross Alice’s field of view, so to avoid frequent 1:00 am phone calls to the Alice team, operations were modified to account for such situations, and Alice would automatically recover and continue operations once the “bad dog” went away.

“However, once Rosetta is on its crash-course descent to 67P on 30 September, there is no further need to have Alice monitor its safety checks because, after all, Alice will be heading “face first” to collide onto the surface of the comet. Since it is important to gather all the data possible until the very last moment before impact, and it is uncertain what conditions Alice and the other instruments will encounter when Rosetta is closer to the comet than ever before, we will disable all the safety checks for those final hours. We’re looking forward to seeing what we get back!”

The Alice team would also like to pay tribute to Michel Festou and Dave Slater, “two wonderful, bright, and positive team members who contributed mightily to Alice in its early days, but were not here to see it reach its destination. They would certainly have been delighted with Alice’s successes.”

---

REAL LIFE TRUMPS ANIMATION

As activity for the Rosetta Flight Control Team steadily winds down toward Friday’s end of mission, we’ve been hearing a number of ‘insider tales’ from the engineers, who are already reminiscing about their favourite moments from Rosetta’s epic journey. This was sent in by Armelle Hubault, spacecraft operations engineer responsible for automation, telecommanding and some of the instruments on Rosetta.

Spacecraft Operations Engineer Armelle Hubault, Rosetta Flight Control Tea, ESA/ESOC. Credit: ESA

This is not a ‘funny’ story as such, but it is one of the most satisfying moments from my time on the Rosetta team, and it happened around the time of Lutetia flyby.

I am very bad at visualising things in 3D; that is, in visualising Rosetta's attitude in space, at the correct position in the Solar System and with other objects around. This was especially so during the long cruise phase, when we were all over the place!

So while I was preparing for Lutetia flyby in summer 2010 , I was using a software package called Celestia to try and picture a bit what was happening. Doing so, I realised the software – which is pretty accurate – was showing me that, as we were approaching the asteroid, Saturn was just in the background. In fact, the software suggested a conjunction situation, in which the asteroid would lie between the spacecraft and Saturn! In other words, it was showing that the view from Rosetta to the asteroid would have Saturn in the background!

Now I know that this kind of simulation should be verified with care, so I contacted a colleague, Michael Küppers, at the Rosetta science operations centre, at ESAC near Madrid, who was dealing with spacecraft pointings and who knew a fair bit about our scientific camera.

I asked him if he could confirm what I was seeing – and whether it would be possible to take a picture? Saturn was very far and dim, Lutetia was very close and bright, and my Celestia software was not capable of determining whether Rosetta’s camera could successfully get such a photo.

After looking at it, Michael confirmed that it was indeed feasible, and the imaging request was added to the spacecraft commands to be sent up near the time of flyby.

The resulting image (see below) is one of which I am very proud, and I could not believe that no one else had noticed this conjunction!

Asteroid (21) Lutetia with Saturn in the background seen from Rosetta in 2010. Credit: ESA/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/RSSD/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

Editor’s note: Read more about Armelle via http://spacewomen.org/space-women/armelle-hubault/

Lutetia flyby

Quelle: ESA