.

13.06.2016

Artist's impression of the simultaneous stellar eclipse and planetary transit events on Kepler-1647.

.

If you cast your eyes toward the constellation Cygnus, you’ll be looking in the direction of the largest planet yet discovered around a double-star system. It’s too faint to see with the naked eye, but a team led by astronomers from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and San Diego State University (SDSU) in California, used NASA's Kepler Space Telescope to identify the new planet, Kepler-1647b.

The discovery was announced today in San Diego at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society. The research has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal with Veselin Kostov, a NASA Goddard postdoctoral fellow, as lead author.

Kepler-1647 is 3,700 light-years away and approximately 4.4 billion years old, roughly the same age as Earth. The stars are similar to the sun, with one slightly larger than our home star and the other slightly smaller. The planet has a mass and radius nearly identical to that of Jupiter, making it the largest transiting circumbinary planet ever found.

Planets that orbit two stars are known as circumbinary planets, or sometimes “Tatooine” planets, after Luke Skywalker’s home world in “Star Wars.” Using Kepler data, astronomers search for slight dips in brightness that hint a planet might be passing or transiting in front of a star, blocking a tiny amount of the star’s light.

“But finding circumbinary planets is much harder than finding planets around single stars,” said SDSU astronomer William Welsh, one of the paper’s coauthors. “The transits are not regularly spaced in time and they can vary in duration and even depth.”

.

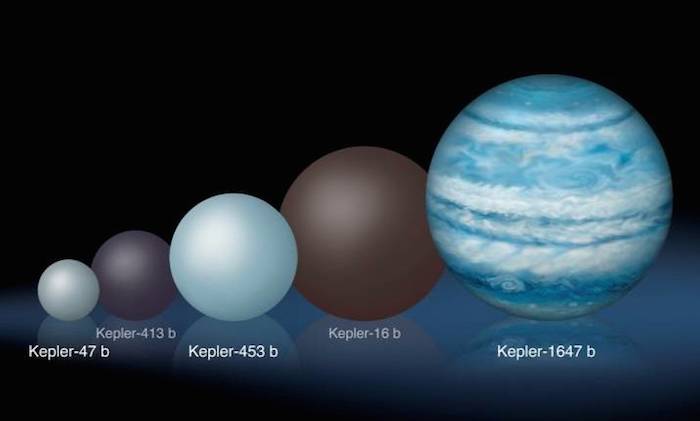

Comparison of the relative sizes of several Kepler circumbinary planets. Kepler-1647 b is substantially larger than any of the previously known circumbinary planets.

Credits: Lynette Cook

.

“It’s a bit curious that this biggest planet took so long to confirm, since it is easier to find big planets than small ones,” said SDSU astronomer Jerome Orosz, a coauthor on the study. “But it is because its orbital period is so long.”

The planet takes 1,107 days – just over three years – to orbit its host stars, the longest period of any confirmed transiting exoplanet found so far. The planet is also much further away from its stars than any other circumbinary planet, breaking with the tendency for circumbinary planets to have close-in orbits. Interestingly, its orbit puts the planet with in the so-called habitable zone–the range of distances from a star where liquid water might pool on the surface of an orbiting planet

Like Jupiter, however, Kepler-1647b is a gas giant, making the planet unlikely to host life. Yet if the planet has large moons, they could potentially be suitable for life.

“Habitability aside, Kepler-1647b is important because it is the tip of the iceberg of a theoretically predicted population of large, long-period circumbinary planets,” said Welsh.

Once a candidate planet is found, researchers employ advanced computer programs to determine if it really is a planet. It can be a grueling process.

Laurance Doyle, a coauthor on the paper and astronomer at the SETI Institute, noticed a transit back in 2011. But more data and several years of analysis were needed to confirm the transit was indeed caused by a circumbinary planet. A network of amateur astronomers in the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope "Follow-Up Network” provided additional observations that helped the researchers estimate the planet’s mass.

.

A bird's eye view comparison of the orbits of the Kepler circumbinary planets. Kepler-1647 b's orbit, shown in red, is much larger than the other planets (shown in gray). For comparison, the Earth's orbit is shown in blue.

Credits: B. Quarles

Quelle: NASA

-

Update: 14.06.2016

.

Largest, Widest Orbit "Tatooine" Bolsters Planet Formation Theories

A team of astronomers, including University of Hawaii astronomer Nader Haghighipour, will announce on June 13 the discovery of an unusual new transiting circumbinary planet (orbiting two suns). This planet, detected using the Kepler spacecraft, is unusual because it is both the largest such planet found to date, and has the widest orbit.

The team is led by Dr. Veselin Kostov, a researcher at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. The work was recently accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal The announcement will be made at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society in San Diego.

Reminiscent of the fictional planet Tatooine in Star Wars, circumbinary planets orbit two stars and have two "suns" in their skies. The new planet, Kepler-1647 b, is Jupiter-sized in radius, the largest of all currently known circumbinary planets, and has an orbital period of 3.0 years, the longest of any confirmed transiting planet.

Nearly half of all Sun-like stars are members of gravitationally-bound binary star systems. The most important subset of these systems are the eclipsing binary stars (stars that pass in front of each other, as seen from Earth), because they provide precise stellar masses and sizes. NASA's Kepler Mission has observed nearly 3000 short-period (less than 1000 days) eclipsing binaries. Among these binaries, only nine have been found to host circumbinary planets, including Kepler-1647.

The detection of Kepler-1647 b is significant for two reasons. First, its large size and large orbit are very different from those of all other known circumbinary planets. All of the previously identified Kepler circumbinary planets are Saturn-sized or smaller. Also, most of these planets tend to orbit close to their host binaries, near the so-called "critical instability radius", where if they orbited any closer, the planet's orbit would be dynamically unstable and the planet would be ejected from the system or crash into one of the stars.

This apparent lack of large circumbinary planets and their proximity to the critical stability limit have left astronomers puzzled. Theoretical models of the formation and dynamical evolution of these planets, developed by Haghighipour and his colleagues, have suggested that "circumbinary planets form the same way planets form around single stars, suggesting that these planets must exist in large sizes, with the larger ones residing far from their host binaries", Haghighipour said. Being a Jupiter-sized planet, the discovery of Kepler-1647 b confirms these predictions.

The second significance of the discovery of Kepler-1647 b is that this planet resides in the Habitable Zone of its host binary, a surprisingly common occurrence for circumbinary planets discovered by the Kepler Space Telescope. Although Kepler-1647 b's large size - similar to Jupiter - means the planet itself is not habitable, "a giant planet similar to those in our solar system may well host undetected large moons that could be habitable" Haghighipour said. According to Haghighipour, the orbit of Kepler-1647 b will remain stable for at least tens of millions of years, increasing the possibility of life forming on its moons.

The Kepler-1647 b system is 3700 light years from Earth, and lies in the direction of the constellation Cygnus. It is estimated to be approximately 4.4 billion years old, roughly the same age as Earth.

The discovery comes five years after the first transiting circumbinary planet, Kepler-16b, was detected. The long wait is because transiting circumbinary planets on long-period orbits (far from their binaries) are much more difficult to detect than close-in planets. Prior to Kepler-1647 b, no long-period circumbinary planets had been found.

"The detection of Kepler-1647 b has been very special to us because after several years of developing a theoretical framework for the formation and evolution of circumbinary planets, we have finally found the objects predicted by our models" said Haghighipour.

Funding for this work was provided in part by NASA.

.

The orbit of Kepler 1647b (white dot) around its two suns (red and yellow circles). Kepler-1647 b was observed transiting each of its two sun during a single orbit (days 0 and 4.3).

Quelle: Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii

5112 Views