Europe’s top rocket contractor is pressing ahead with development of the Ariane 6 rocket, a versatile launcher with half the cost of Europe’s current Ariane 5 booster, keeping the new vehicle on track for its 2020 debut.

The rocket cleared a major design review in June, and there are no signs of slowdowns in a multibillion-dollar program that is as much of an exercise in cost-cutting as technical development.

At the same time, engineers are evaluating what it might take to convert the Ariane 6 into a partially reusable rocket, including a new methane-fueled engine that could be plugged into the Ariane 6’s first stage and a booster recovery system to return the engine to the ground for another mission.

But Europe’s biggest rocket developer, Airbus Safran Launchers, is sure the Ariane 6 will answer the near-term needs of European governments and commercial satellite operators, who seek lower prices and multiple reliable launch options.

Alain Charmeau, chief executive of Airbus Safran launchers, told Spaceflight Now he is “extremely confident” the Ariane 6 will be ready for a maiden test flight by the end of 2020, and will fully replace the Ariane 5 in 2023.

Between 2020 and 2023, ground teams will ramp up the Ariane 6 production and launch rate, eventually reaching a cadence of 11 or 12 flights per year. Officials anticipate five Ariane 6 missions per year will be for European institutional customers, including the European Space Agency, the European Commission and individual member states. The balance of the manifest will be filled with commercial payloads.

A top aim of the Ariane 6 project is to guarantee European spacecraft can ride to orbit aboard a European rocket — the goal of independent access to space — while ending public sector support once the rocket is operational.

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Alain Charmeau. Become a member today and support our coverage.

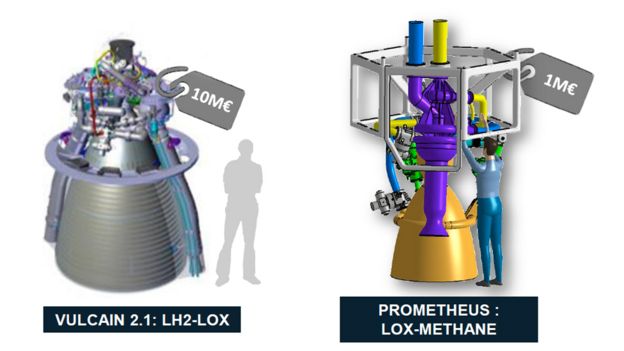

The new rocket’s first stage will use the same type of hydrogen-burning Vulcain 2 engine currently flying on the Ariane 5’s core. Its upper stage will fly with the new Vinci engine, which was originally supposed to go into an upgraded version of the Ariane 5 and has been in off-and-on development since 1999.

Both stages of the new launcher will have a diameter of nearly 18 feet (5.4 meters), the same size as the Ariane 5, allowing much of the tooling inside European rocket factories to be repurposed with minimal changes.

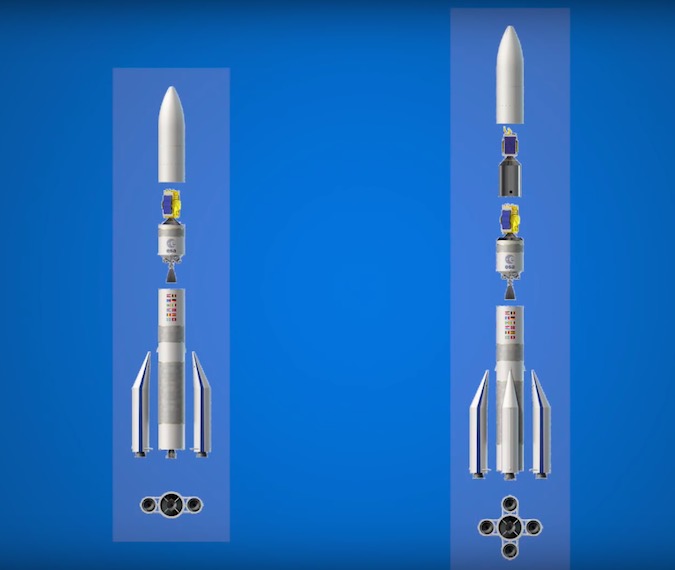

The 206-foot-tall (63-meter) Ariane 6 will come in two varieties — the Ariane 62 with two solid rocket boosters and the Ariane 64 with four strap-on motors — and will be able to launch satellites into low Earth orbit, geostationary transfer orbit, or a range of other orbits, plus Earth escape trajectories.

The P120C strap-on motors are based on the first stage of Europe’s Vega C rocket, a design decision intended to reduce overhead and launch costs.

The solid-fueled Vega booster is an Italian-led program. Vega’s lead contractor is ELV — a joint venture led by Italy’s Avio aerospace developer and the Italian Space Agency — while the Ariane 6 is primarily led by companies in France and Germany, with smaller contributions from Italy, Switzerland and other European states.

The Vega C is an upgraded, more powerful version of the current Vega booster. It will haul heavier cargo into orbit and start launching in 2018.

The Ariane 6’s commonality with the Ariane 5 and Vega C, coupled with the upper stage’s Vinci engine already in testing, gives the new launcher a head start in development.

“We did not start this launcher from scratch but from either existing hardware or an engine which has been under development, and which is almost qualified now,” Charmeau said.

Unlike the Ariane 5’s existing cryogenic upper stage engine, the HM7B powerplant borrowed from Europe’s previous Ariane 4 launcher, the Vinci can ignite multiple times during a flight. That will allow the Ariane 6 to put satellites in different types of orbits, easing the placement of multi-satellite constellations and releasing communications payloads closer to their final posts in geostationary orbit, reducing the fuel the spacecraft need to carry.

Test models of the Vinci are already being test-fired.

Airbus Safran Launchers is a 50-50 joint venture formed in January 2015 between Airbus and Safran, the companies which managed the bulk of production of the Ariane rocket family’s structures, tanks and engines. Airbus and Safran finalized the joint venture June 30, with Safran paying Airbus 750 million euros (nearly $840 million) to establish equal ownership of the Ariane design offices and production lines.

The new company has 8,400 employees across France and Germany, and has 11 subsidiaries and affiliates, including Arianespace, which oversees sales and operations of the Ariane 5, Ariane 6, Soyuz and Vega rockets at a launch base in Kourou, French Guiana.

Airbus and Safran took responsibility for designing the Ariane 6 rocket from CNES, the French space agency, in a bid to ensure the new launcher can meet tight pricing constraints sought by government and commercial satellite owners.

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, which currently sells for about $61 million, has put the European launcher community on its heels. The Ariane 5 rocket still won a slight majority of competitively-procured launch contracts awarded last year for satellites heading to geostationary orbit.

But that may not remain the case, as SpaceX strings together a rapid-fire launch cadence with Falcon 9s taking off, on average, than once per month. SpaceX has also recovered five Falcon 9 first stage boosters and hopes to transition the dramatic landing attempts from being purely experimental toward becoming a vital part of the company’s economic calculus.

SpaceX officials have said they hope to knock off about 30 percent from the Falcon 9’s current launch price when the rockets fly with previously-used first stage boosters. That price could come down further if SpaceX can master rapid turnarounds between landings and launches, said Gwynne Shotwell, the company’s president chief operating officer, in an interview with Spaceflight Now earlier this year.

With Falcon 9 launch prices of $40 million potentially on the horizon, most of SpaceX’s competitors believe they need new offerings.

The Ariane 6’s four-booster configuration, called the Ariane 64, will be the Ariane 6 version that likely flies most often. It can loft up to 10.5 metric tons — more than 23,000 pounds — into geostationary transfer orbit, the destination favored by most commercial communications satellites.

That capacity is just above the Ariane 5’s capability today, and will allow engineers to fit two large communications stations on a single Ariane 6. The dual-payload launch scheme is already in practice with the Ariane 5, but the Ariane 64 should fly for about $100 million, bringing the per-satellite price near current Falcon 9 levels.

“Ariane 6 will reduce the cost of our launchers by 50 percent compared to today,” said Gaele Winters, ESA’s director of launcher programs. “You have to realize that, in just four years, we are reducing the cost of a launcher within Europe by 50 percent. That is, of course, a major step. If you think about Ariane 6 in a double-launch configuration, we are able to offer a price which is really, really attractive in comparison with the competition.”

The Ariane 62’s launch price is forecast to be around $80 million, tailored to deliver up to 7 metric tons — more than 15,000 pounds — to low polar orbits often used by Earth observation satellites.

Other launch providers are expected to be more aggressive in the commercial market. International Launch Services, the U.S.-based company that sells Proton launches commercially, has cut prices to lure business after the Proton’s recent reliability woes. And United Launch Alliance officials say the business case for the new Vulcan launcher, a replacement for the Atlas 5, requires at least some commercial customers.

So will the Ariane 6 be competitive?

“We have to be,” Charmeau said. “We will be competitive. We will use an Ariane 6 with competitive technologies, such as solid propulsion and cryogenic propulsion, which are more efficient than other ones. We will have a big launcher, Ariane 64, to allow for dual-launch of two big satellites, which is also a way to reduce the cost per customer.”

With industrial facilities now under the umbrella of Airbus Safran Launchers, Charmeau said his team is already turning attention to a smooth startup on the Ariane 6 assembly lines. Technicians will integrate the Ariane 6 core stage in Les Mureaux, France, northwest of Paris, and engine work is centered in nearby Vernon.

Final assembly of the Ariane 6 upper stage will occur in Bremen, Germany.

Those same production plants are currently involved in the Ariane 5 program.

“We want to go directly into production for Ariane 6, and I would say the development is not really the most worrying part of it,” Charmeau said. “We want to really pay attention to how to set up the production, and how to ramp up the production as quickly as possible.”

Later this year or in early 2017, Arianespace will likely place orders for a final batch of Ariane 5 rockets and an initial purchase of Ariane 6s. The contract will set the final number of Ariane 5 launchers to be flown, effectively starting the countdown clock to its planned retirement in 2023.

The Ariane 6 must be ready to take over as the Ariane 5 flies out its manifest, according to Charmeau.

“We will have an on-ramp, or transition, phase between 2020 and 2022, and our target is that by 2023 we have only Ariane 6 flying,” he told Spaceflight Now. “This is a transition period with one Ariane 6 in 2020, and six or seven Ariane 5s, to the end of the transition, where we will have no more Ariane 5s in 2023.”

Airbus Safran Launchers signed a 2.4-billion-euro ($2.7 billion) contract with ESA in August 2015 to develop the Ariane 6. That deal included a commitment of 680 million euros (about $760 million) in ESA funding to carry the Ariane 6 development through a preliminary design review.

The rocket program is also getting a commercial investment of 400 million euros (about $450 million) from Airbus Safran Launchers.

“We don’t wait for all the decisions to be taken,” Winters said. “One of the ambitions of this program is to have the launcher — Ariane 6 — available in 2020, which is only a few years (away). So we have to do the complete development project to be ready for a first launch in 2020.”

Charmeau said the Ariane 6 passed its preliminary design review in June, and ESA member states are expected to clear the release of the rest of the contract money during an ESA Council meeting Sept. 13.

“The design configuration is frozen, and 12 months from now, we will have started the production of some parts of the launcher, at least for ground testing,” Charmeau said.

Airbus Safran Launchers is sticking with a throwaway design for the Ariane 6, and Charmeau said the company will take cues from its customers, not competitors like SpaceX.

“We believe what the customers are expecting is not a reused launcher,” he said. “I am convinced they would prefer to buy a new launcher than a second-hand launcher, but they want to reduce the cost. We are working intensely on cost reduction.”

Airbus Safran Launchers argues that the Ariane 6 will be less expensive than the Falcon 9’s current prices on a cost-per-kilogram basis, and many European officials, while impressed by SpaceX’s rocket landing achievements, are unconvinced the successful introduction of a reusable booster will lead to significant cost reductions on the orders-of-magnitude scale predicted by SpaceX founder Elon Musk

Managers leading the Ariane 6 program intend to cut costs by organizing the rocket’s production and launch operations into a vertical integration, taking a page from SpaceX’s strategy of building most of its rockets and spaceships in-house. There are also advantages through economies of scale — the Ariane 6 will fly up to a dozen times per year — and a wider sharing of industrial overhead costs with the Vega rocket program.

Engineers also found shortcuts in Ariane 6’s technical design and concept of operations. For example, the new rocket will employ 3D-printed parts inside its engines, easing the time and cost of production.

“The approach on Ariane 6 is when we design it, we’re asking why we cannot use 3D printing,” Charmeau said. “Obviously, we cannot do it for big structures, when we have structures of 5-meter (16-foot) diameter. We cannot do 3D printing (there) because the machines are not available, but for any piece of the launcher which fits with the size of the machines for 3D printing, we will do it.”

The Ariane 6 will also use a pyro-laser ignition system, relying on focused light beams to spark the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants inside the rocket’s Vinci upper stage engine. No such system is in use on a large rocket engine today.

There are also changes at the Ariane launch base in French Guiana. The new Ariane 6 launch pad, a few miles to the northwest of the Ariane 5’s existing launch facility, will have a large hangar for ground crews to put together the major parts of the rocket horizontally.

Horizontal integration is nothing new in the rocket business. Russian boosters have been assembled on their side for decades, and the Falcon 9 and Delta 4 rockets in the United States are mostly integrated horizontally.

But Ariane rockets up to now have been stacked vertical on top a launch table. Managers found out the launch campaign could be shortened if that changed on Ariane 6.

“The result of the tradeoff is that it was cheaper to do it horizontally than vertically,” Charmeau said. “It’s as simple as that. It was not done in Ariane 5, so for us it is something new, and we are going to drastically reduce the integration cycle and integration costs for Ariane 6 compared to Ariane 5.”

The Ariane 6’s satellites will still be added on top of the rocket after it rolls out and stands upright on the launch pad.

“We know our customers like to do it this way,” Charmeau said.

In Airbus Safran Launchers’ search for savings, officials have not turned their backs to the benefits of reusability. But the clear priority has been in finding ways to slash costs in other areas.

“Of course, the cheaper you are the less interesting reusability becomes because we know there are costs in order to recover and reuse a launcher,” Charmeau said. “But if a launcher is very cheap, it’s more competitive to have an expendable launcher than a reusable one.”

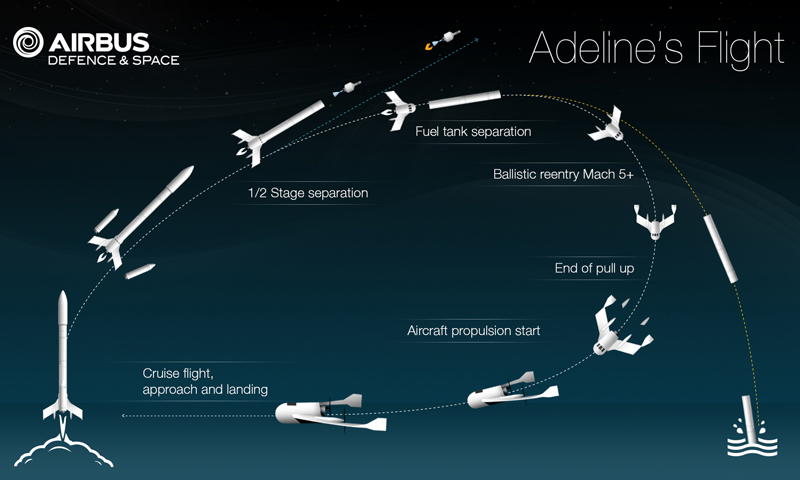

Nevertheless, Airbus kicked off a research and development effort in 2010 to investigate how to eventually pursue reusability for the Ariane rocket family. The result was Adeline, a fully automated re-entry module that would break off from the base of a rocket’s first stage, start up turbofan engines, and return to a runway landing with the booster’s core engine and avionics package.

Charmeau said Airbus Safran Launchers continues working on the Adeline program with its own private funds. Officials last year said Airbus had spent about $15 million on the program through 2015.

Early tests have included low-altitude flights of a sub-scale version of Adeline at a French airfield.

The Ariane 6’s design is compatible with the potential addition of a recoverable engine module, Charmeau said, if European governments want to back it.

The avionics and main engines represent between 70 and 80 percent of the total cost of a launch vehicle, according to Airbus, and those expensive components could be returned to Earth with less fuel than SpaceX needs to set aside for recovery. Instead, the propellant could be applied to add lift performance for payloads, officials said.

Airbus officials said last year that reusing the engines and avionics could result in a cost reduction of up to 30 percent, the same figure publicized by SpaceX earlier this year.

“We are convinced that it could be a competitive concept, but for the moment our priority is Ariane 6 because we believe, and hear our customers believe, Ariane 6 will be competitive,” Charmeau said. “Then we have two (projects) for the future. One is to develop a new liquid engine, a big engine, in order to drastically cut down the cost of this engine compared to today, and the other concept is how to use the Adeline design in order to make a reusable launcher maybe one day. Whether it will be an evolution of Ariane 6 or a new launcher, like Ariane 7, we cannot say today.”

Charmeau declined to offer many details on the next-generation engine. Called Prometheus, the engine will burn methane and liquid oxygen, and early development of the new powerplant began a few months ago.

He said the Prometheus engine will have about the same power as the Vulcain 2, the Ariane 6 rocket’s initial core engine. The Vulcain 2 generates approximately 300,000 pounds of thrust.

“We are cautious, and we prefer to speak when are sure of what we announce. That’s why sometimes we don’t speak a lot,” Charmeau said. “It’s European culture, I would say. But certainly this engine could very well fit with the first stage of Ariane 6 one day.”

Quelle: SN

-

Update: 14.09.2016

.

ESA gives final approval for Ariane 6; Airbus Safran Launchers now in control

PARIS — The European Space Agency (ESA) on Sept. 13 gave final go-ahead for development of the next-generation Ariane 6 heavy-lift launch vehicle, confirming a rendezvous that many thought impossible when it was set in December 2014.

Meeting at ESA’s headquarters here, the agency’s ruling council approved the release of the second and final tranche of funds for Ariane 6, with the transfer of funds to Ariane 6 prime contractor Airbus Safran Launchers to occur in late October.

The contract’s, whose financial contours have already been determined since its signature in August 2015, is for 2.4 billion euros ($2.7 billion) for the development of the Ariane 6 under Airbus Safran Launchers leadership.

A bit more than a quarter of that sum, 680 million euros, was paid out after the August 2015 signature. It is the remaining piece that was withheld pending a Program Implementation Review that ESA governments insisted on just to be sure they were not buying something they did not want. The funds’ release will now be validated by ESA’s Industrial Policy Committee, scheduled to meet in late October.

To these figures are added 600 million euros to be paid to the French space agency, CNES, to build the new Ariane 6 launch complex at Europe’s Guiana Space Center on the northeast coast of South America.

Another 400 million euros is coming from the principal industrial contractors building Ariane 6.

ESA’s Gaele Winters: Technical performance of Ariane 6 is clear

Gaele Winters, ESA’s outgoing director of launchers — his last day on the job was Sept. 13 — said the Ariane 6 is on track both in its technical design, performance requirements and schedule.

In an interview, Winters said the vehicle is still scheduled to fly in 2020. The current thinking is that the existing Ariane 5 would be operated in parallel until 2023. But the precise Ariane 5 phase-out schedule will be the subject of what Winters called an Exploitation Verification Key Point, to occur by the end of 2017.

Government guaranteed launch rate to be discussed later

Also to be determined then is whether and how European governments will guarantee to Airbus Safran Launchers five contract per year. The company has said it needs this minimum government guarantee to close the business case.

Winters said several ESA governments remain concerned that their industry will not receive contracts corresponding to the amount of their governments’ contributions to the Ariane 6 program. This issue, known at ESA as fair return or industrial return, is a pillar of ESA management.

Winters said he saw no serious issues there and that assuring the necessary return for all governments contributing to Ariane 6 will be part of the relatively easy adjustments to be made starting in 2017.

The biggest government customer for Europe’s Arianespace launch consortium is not ESA but the European Commission, the executive arm of the 28-nation European Union.

It is the commission that owns Europe’s biggest government space programs, the Galileo positioning, navigation and timing network and the Copernicus Earth observation system.

The commission is developing a space strategy for Europe that will not be published until late October. The consequences of this policy, and how to provide the Ariane 6 contractors a minimum annual government launches, will be a subject of debate starting in 2017.

Other details for Ariane 6 are not viewed as urgent but are nonetheless key to the program’s ultimate success. For example, it is not yet clear who has what responsibility in the event of an Ariane 6 failure.

“We are in a development phase now, and topics like this need to be addressed for the exploitation phase,” Winters said. “The exploitation review in late 2017 will treat aspects including the financial environment of the vehicle’s exploitation and other topics that do not need to be handled now.”

As a result of the Sept. 13 council decision, Ariane 6 will not be on the agenda for ESA governments when they meet in Switzerland in early December to discuss ESA’s mid-term budget and policy direction.

Once the funding complement is released, CNES is expected to proceed with the sale of its 35 percent share of Arianespace to Airbus Safran Launchers, a transaction valued at about 150 million euros.

ESA will remain a “censor” on the Arianespace board of directors, keeping at least a symbolic government hand in the launcher business despite CNES’s departure as an Arianespace shareholder.

Quelle: SN

-

Update: 16.09.2016

.

Clear path to Ariane 6 rocket introduction

The company set up to manufacture Europe's next-generation rocket - the Ariane 6 - says it is open to orders.

Airbus Safran Launchers (ASL) expects to introduce the new vehicle in 2020.

This week, member states of the European Space Agency gave their final nod to the project following an extensive review process.

The assessment confirmed the design and performance of the proposed rocket, and the development schedule that will bring it into service.

Esa has earmarked R&D funds of €2.4bn for the Ariane 6. Twenty-eight percent of that sum was given to ASL in August 2015. The completion of the review, and the member states' acceptance of it, means the balance should now follow.

"Now that we are sure that the development programme will go through to the end, Arianespace will start marketing the Ariane 6," said Alain Charmeau, the CEO of ASL.

"I am sure there will be many commercial satellite customers out there who will want to have Ariane 6 in their order books for 2021," he told BBC News.

ASL is about to take a majority shareholding in Arianespace, the company that has traditionally sold the payload space on Ariane vehicles.

This change in ownership is the last part of a major reorganisation in Europe's rocket industry that seeks to keep it competitive into the future.

Image copyrightDLR

Image copyrightDLR

The current Ariane 5 vehicle, although remarkably reliable and consistent in its performance, costs substantially more to build and launch than some of its competitors - in particular, the Falcon 9 rocket operated by SpaceX in the US.

The Ariane 6 is Europe's response. It aims to halve the 5's cost-per-kilo for putting satellites in orbit.

Industrially, this requires a transformation of the rocket production process: to use fewer people, more streamlined ways of working, and new fabrication techniques.

The Ariane 6 will come in two versions. One, known as Ariane 62, will loft medium-sized spacecraft into orbit - the kind of platforms that image and study the Earth.

A second version, known as Ariane 64, will put up the heavy telecommunications spacecraft, which sit 36,000km above the equator.

The new rocket leans heavily on its heritage. Indeed, its upper-stage engine, called Vinci, was originally intended for an upgrade of the Ariane 5.

Prototype Vinci test firings have been conducted through the summer.

Image copyrightASL

Image copyrightASL

Although the design for the Ariane 6 is frozen, ASL is already looking to evolutions of the vehicle that could bring down its costs still further.

One proposal is to replace the Vulcain engine at the base of the rocket with an all-new propu