The Great Red North: Nunavut’s ‘Martian colony’ has become go-to spot to field-test extra-planetary tech

For the 16th year running, a team of NASA-backed scientists are flying into the remote barrenlands of Nunavut’s Devon Island to mimic life in a Martian colony.

“[It] just takes you to Mars as soon as you go there,” project director Pascal Lee told a CBC camera crew during a weekend stopover in Iqaluit.

Mr. Lee, a veteran of Antarctic research, first proposed the idea of a High Arctic Mars simulator while in post-doctorate studies at Cornell University. The National Research Council soon shined to the idea, and by 1997, Mr. Lee was on his first exploratory trip to the island’s 20-kilometre-wide Haughton Crater.

Smashed into the tundra 20 million years ago by a hunk of errant space debris, the crater is ringed by networks of canyons and channels that are “astonishingly” similar to Mars, Mr. Lee said in a 2008 web video.

Today, the crater is home to two separate space-research facilities. The cylinder-shaped Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station (FMARS), constructed in 2000, is operated by the Mars Society, an international non-profit devoted to the exploration and ultimate settlement of Mars.

Mr. Lee’s Haughton-Mars Project (HMP), which shares an airstrip with FMARS, is backed by NASA, the Canadian Space Agency, the U.S. Marine Corps and a litany of private sponsors.

“If our micro-scale experience on the NASA HMP analog project has been any indication, going to Mars, if initiated through a government effort, would likely draw in significant participation from the private sector,” Mr. Lee wrote in 2002.

Two specially equipped Hummers, driven to the site in dramatic winter journeys over the frozen Northwest Passage, are on hand at HMP to simulate overland expeditions across the Martian surface (at a typical Martian rover speed of about 10 km/h). The Arthur Clarke Mars Greenhouse, installed on the site in 2002, is wired with sensors and communications systems to autonomously grow hydroponic plants under harsh conditions. At times, to simulate the conditions that would be faced by Martian astronauts, radio communications between “ground control” and HMP crew members are handicapped with a 20-minute delay.

Of course, while Devon Island is one of the world’s best Mars “analogs,” the simulation can only go so far. On its website, the neighbouring FMARS project wrote that its project is similar to “camping in a RV,” with crews routinely forced to “break the simulation” to collect water, refuel generators and perform other camp-related tasks. Also, unlike actual interplanetary explorers, the FMARS crew must keep a loaded shotgun on hand to guard against invading polar bears.

Science author Mary Roach, who visited HMP in 2008, praised the site’s “inconvenience.” “Doing science here is a lesson in extreme planning,” she wrote in her 2010 book Packing for Mars. “A moon or Mars analog, rather than the orb itself, is the place to figure out that, say, three people might be a better size for an exploration party than two.”

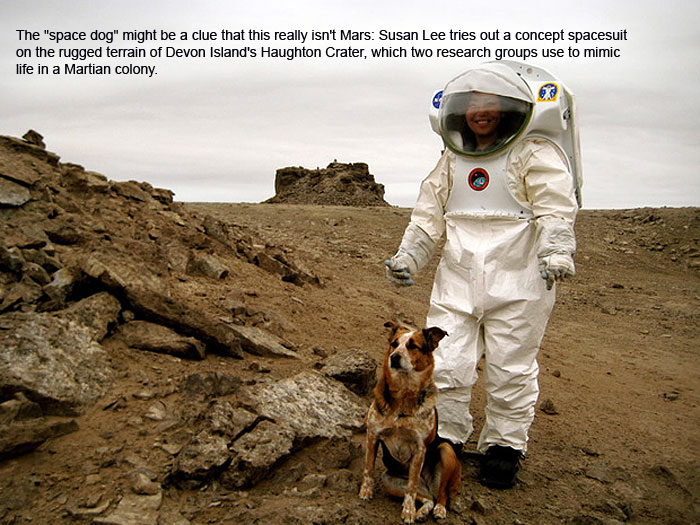

The rugged, rocky terrain of Devon Island has also made it a go-to spot to field-test emerging robotics or extra-planetary technologies.

In 2010, a team from NASA’s Intelligent Robotics Group flew to the site to deploy K-10, an unmanned rover designed to follow behind human explorers, collecting soil samples, topographic models and other “tedious” data. Wearing bulky spacesuits, Mr. Lee and others have rappelled off cliffs and embarked on long-distance journeys. This season, the HMP team is expected to continue tests of a robotic rock drill.

Quelle+Fotos: Mars Institute

5556 Views