.

Jupiter and five moons

These annotated images, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, show Jupiter with five of its moons: Io, Callisto, Europa, Amalthea and Thebe.

February 6, 2015, 12:36 a.m.

NASA, ESA and Z. Levay (STScI/AURA)

.

Here's a photo-op pretty enough to tempt any astronomer. With a series of well-timed shots, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has managed to catch three of Jupiter’s biggest moons whizzing across its surface in the same frame.

This Jovian lunar gathering, which took place Jan. 24, is a relatively rare event -- it happens only once or twice a decade. Hubble had to snap a series of images in fairly quick succession to capture the brief moment when all three could be seen hovering over the colorfully banded planet.

The three moons, Europa, Callisto and Io, are three of the four Galilean satellites -- so named because astronomer Galileo Galilei discovered them in 1610. (The largest, Ganymede, was off-screen and too far to be considered part of the conjunction.) These four moons are Jupiter’s largest, and among the largest bodies in the solar system.

To put that in perspective: these four moons are bigger than all the dwarf planets, Pluto and Ceres included. Three of them (Ganymede, Callisto and Io) are all larger than Earth's moon, and Ganymede is larger than the planet Mercury.

In this image, the Jovian moons are traveling from the bottom left toward the top right as they cross Jupiter’s midriff, and their shadows are cast far in front of them; near the beginning of conjunction, Callisto’s shadow looks like it’s almost directly beneath Io.

The Hubble images also showcase in a single frame how different each of these moons are. Io, the leading moon at the top right, is an orange-yellow world, riddled with active volcanoes. Callisto, second in line, is ancient, cratered and brownish in color. Europa, the trailing moon in the bottom left, is a yellow-white, reflecting the ice covering its frozen exterior. (Europa has come to the forefront recently as one of the "water-worlds" in our solar system that may hide a subsurface ocean, and hold the potential for life.)

The shadows give away how far the moons are from the surface: A sharper shadow means the moon is close to Jupiter’s thick cloud tops, and a fuzzier one means it’s farther away, as the shadow spreads out over larger distances. Io, the innermost Galilean satellite, has a shadow like a clean circle; Callisto, the farthest of the four major moons, leaves a much fuzzier outline.

Jupiter’s Galilean satellites have a special place in the history of astronomy: showing that tiny celestial bodies were orbiting larger ones directly contradicted the Aristotelian view of the heavens, which held that all bodies -- the planets, the moon, even the sun -- circled the Earth. More than two decades later, Galileo was put on trial during the Roman Inquisition for presenting a "Copernican" view of the solar system. He was placed under house arrest, where he remained until his death.

Quelle: Los Angeles Times

-

Spechtel-Tips für die nächsten (hoffentlich) klare Nächte:

Jupiter reaches opposition on February 6, 2015. Find out how to see the planet king at its best.

If you've ventured out at night this winter season, you may have noticed the dazzle of Jupiter among the stars of Leo and Cancer. This is undoubtedly the best time of the year to view the king of the planets. It reaches opposition on February 6th, which means that — assuming clear weather and dark skies — it's easily spotted with the naked eye from dusk to dawn. Appearing low in the east at twilight, Jupiter rises through the southeast sky to shine high in the south around midnight. It's bright this month, too, opening February at this year's peak magnitude of –2.6 and dimming only to –2.5 by month's end. It's not surprising that Jupiter's a favorite target for naked-eye observing. It's up all night, it's bright, and its distinctive yellow-orange color makes it easy to identify.

Jupiter is also a favorite target for observers with binoculars and telescopes, partly because of the variability of its features. As S&T Senior Editor Alan McRobert noted recently, "There's always something happening on Jupiter," and even a modest telescope can be used to see the subtly shifting "stripes" that comprise the planet's zones and belts. Move up to a 6-inch scope and add an appropriate filter, and the horizontal bands become even more readily apparent.To highlight the Great Red Spot and the burnt-umber equatorial belts, experiment with blue (Kodak Wratten number) 38A; medium blue 80A; or light blue 82A filters. Try a yellow 8 or 12, or even a yellow-green 11, to darken the blue festoons (the thin, dark streamers that cut from belt to zone) or to increase the contrast in the polar regions. If you're having trouble detecting the festoons, consider a red 21, 23, or 25. I've found that a red filter really increases the visibility of the blue regions. It should also sharpen the definition between the zones and belts.

But don't let me determine your filter choice. Although generally it's good advice to use a filter opposite in color to the feature you're trying to highlight, Jupiter is a quickly-changing target and observing preferences aren't universal. Filters may help, but they're not required! Visit John McAnally's observing guide for more tips on observing Jupiter.

Almost any kind of Jupiter observation requires familiarity with the correct names for the various belts and zones. Here south is up; in an inverting telescope such as a Newtonian reflector, or a refractor, Schmidt-Cassegrain, or Maksutov used without a star diagonal, north will be down and east to the right. Telescopes used with a star diagonal will have north up but east and west reversed. The planet's rotation causes features to move from east (following) to west (preceding).

Sky & Telescope Illustration

Jupiter rotates quickly — a revolution takes just under 10 Earth hours — so even a few hours of viewing can bring a lot of variety to the eyepiece. And if you return to Jupiter night after night, year after year, the changes might seem dramatic. For example, the size, shape, and color of the Great Red Spot has changed with time; as the storm continues to rage, it rotation period has changed, along with its maximum wind speed. If you'd like to study this feature for yourself, take advantage of the S&T Great Red Spot JavaScript Utility.

The mutable nature of Jupiter's features make the planet an observing challenge: although easily located in the sky, you could spend the rest of your life swapping out filters and eyepieces to study zones, belts, rifts, and storms.

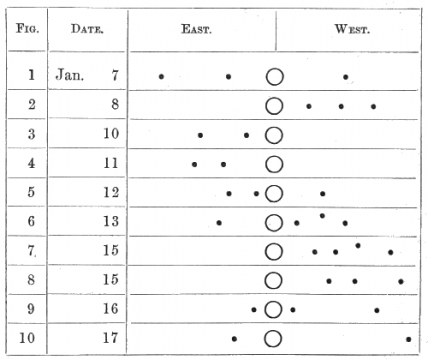

Truthfully, telescopes aren't even required for the most fun you'll have with this planet. A set of hobby binoculars will reveal some of Jupiter's best features: its moons. In my 8 x 42 binoculars, Jupiter is a gleaming white disk, noticeably broader than a star. Flanking the disk, in a slightly ragged formation, are three (or four, on a good night) star-like points. These gleams are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, the Galilean moons, named so after Galileo Galilei, who first spotted them through a telescope. Galileo noted the location of the moons each night for several months and included a chart of their locations in his 1610 book, Sidereus Nuncius (Sidereal Messenger).

Original configurations of Jupiter’s satellites observed by Galileo in January, February, and March 1610, and published with the 1st edition of his book Sidereus Nuncius, Venice, 1610.

Project Gutenberg

There are plenty of tools for predicting the location of Jupiter's moon available today, including our own iPhone/iPad app, JupiterMoons, and our Jupiter's Moons JavaScript Utility, but replicating Galileo's chart is a good beginning observing project. Which is more challenging to see, the planet-hugging Io and Europa, or the wide wanderer Callisto? How long does it take Ganymede to circle Jupiter? Let us know the outcome of your royal visit(s)!

Quelle: Sky&Telescope

4996 Views