.

If Mars is mysterious, Venus is truly scary. Long called Earth’s twin, it’s only four months away via unmanned probe and lies more than 70 percent of Earth’s distance from the Sun.

But with surface pressures and temperatures high enough to melt lead and crush steel, why is Venus so hauntingly different from Earth? And when did it go bad?

“Venus and Earth are virtually identical twins; they’re almost the same size,” said Robert Herrick, a planetary geophysicist at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. “But Venus is completely uninhabitable; we really don’t understand how that dichotomy came about.”

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Venus Express orbiter has spent the last eight years trying to dissect its hellish atmosphere and surface. But now with dwindling fuel, by year’s end the spacecraft is expected to make its final plunge into Venus’ toxic atmosphere.

.

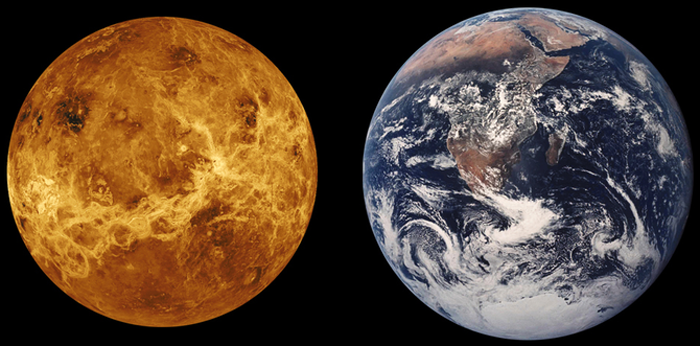

Scale representations of Venus and the Earth shown next to each other. Venus is only slightly smaller.

.

While Venus Express has made scientific progress, planetary scientists say, a few major puzzles have yet to be solved.

Larry Esposito, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado at Boulder, says the most puzzling things are: How did Venus go bad? How did the high-wind dynamics of the atmosphere arise on Venus? What is its surface made of? And does Venus still have volcanic activity?

Venus Express took infrared images of the planet’s surface and found that its biggest volcanoes do indeed indicate lava flow there within the last 250,000 years.

“Venus Express also detected a sudden increase in sulfur dioxide; the same thing that comes out of unscrubbed coal-powered plants on earth,” said Esposito. “But on Venus Express, it was interpreted as a possible real-time volcanic eruption.”

One explanation is that Venus undergoes giant volcanic eruptions every few decades. But how do these putative eruptions contribute to Venus’ ongoing dense, noxious atmosphere?

Calculations of surface-atmosphere interactions indicate that the planet’s atmospheric sulfur should be “sopped up” by the surface in a few tens of millions of years, says Kevin Baines, a planetary scientist at NASA JPL and the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Baines says this means if the present cloudy atmosphere is typical and ongoing, then there must be active volcanism to resupply the atmosphere with sulfur. He notes that “a hot atmosphere” may “soften” the surface, allowing increased sulfur emission.

One of a handful of potential Venus mission proposals — each vying for a slot in NASA’s Discovery-class mission program — could help clear up Venus’ remaining mysteries.

A proposed VASE (Venus Atmosphere and Surface Explorer) mission might skim the clouds and on a final landing even get data from the surface, says Mark Bullock, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, and a VASE definition team member.

But Bullock says “if you really want to understand this you have to put lots of balloons in the atmosphere to understand how the surface and the atmosphere interact.”

As for why Venus ultimately became so inhospitable?

The short answer is that as the Sun increases in luminosity, the inner edge of our solar system’s habitable zone also continually moves outward; thus, long ago, Venus simply became too hot to hold onto its liquid water.

This loss, says Baines, was likely caused by the “ravaging solar wind” and the effects of ultraviolet photons “ripping water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen,” which in turn led to the escape of Venus’ hydrogen into space.

“To me, the main puzzle is when did Venus lose its oceans,” said Bullock. “The paradigm is that Venus lost its oceans up to 600 million years after its formation. But there is absolutely no data which contradicts the possibility that Venus was actually Earth-like for billions of years.”

Could Earth suffer a similar fate?

“Earth is definitely on a path to a Venus-like condition and anthropogenic carbon emissions are the beginning of it,” said Bullock. “That’s dramatic, but there’s no question that Earth will go in that direction.”

As for finding proof of Venus’ ancient lakes or seas, Baines says a surface lander that sampled rocks and found water-bearing materials or materials that could only be formed in standing water would clinch that.

However, Bullock says there are also people who think it may not ever have had an ocean and its water was always steam.

In terms of our geological understanding of Venus, Herrick says we’re where we were with Mars three decades ago. NASA’s 1990s Magellan mission to Venus was only able to see things several football fields across and larger. But he says a newer generation of Synthetic Aperture Radars (SAR)s is capable of giving researchers much better images.

For a planet with a dense atmosphere, like Venus, Herrick says synthetic aperture radar would image the surface and researchers would interpret the black and white image results very much like images from planets with more transparent atmospheres.

A proposed RAVEN (Radar at Venus) mission would compare a new radar-imaging orbiter focused on understanding Venus’ geology as well as identifying future potential landing sites. One of its goals would be to definitively determine whether Venus has continents and whether such putative continents are composed of granitic rock, as here on Earth.

“We don’t know that the high-lying regions on Venus are actually like Earth’s continents,” said Esposito. “We haven’t identified granite yet on Venus and don’t know its major surface rock types.”

Venus doesn’t have Earth-styled plate tectonics, says Herrick, but he says we don’t have enough high-resolution topography information to understand how Venus is releasing its heat.

NASA will put out a Discovery mission Announcement of Opportunity this September. By year’s end, the agency is expected to then pick three to five proposals for further study. Conceivably, one or more of a handful of competing Venus mission proposals may ultimately be chosen and see launch as early as 2020.

As for longer range Venus missions?

“New missions that orbit the planet for decades,” said Baines, “may allow us to complete the picture of what happened to Venus to convert it from a verdant oasis to a (non)living hell.”

Quelle: Forbes

5011 Views