.

The Cassini spacecraft has spotted what seem to be tiny waves on the seas of Titan.

.

After years of searching, planetary scientists think they may finally have spotted waves rippling on the seas of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. If confirmed, this would be the first discovery of ocean waves beyond Earth.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft spied several unusual glints of sunlight off the surface of Punga Mare, one of Titan’s hydrocarbon seas, in 2012 and 2013. Those reflections may come from tiny ripples, no more than 2 centimetres high, that are disturbing the otherwise flat ocean, says Jason Barnes, a planetary scientist at the University of Idaho in Moscow.

Barnes presented the findings today at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, where a second talk hinted at the presence of waves in another of Titan’s seas.

Researchers expect more waves to appear in the next few years, because winds are anticipated to pick up as Titan’s northern hemisphere — where most of its seas are located — emerges from winter and approaches spring.

“Titan may be beginning to stir,” says Ralph Lorenz, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “Oceanography is no longer just an Earth science.”

On its many flights past Titan, Cassini discovered small lakes and large seas of methane, ethane and other hydrocarbon compounds1. Liquid rains down on the moon’s surface and then evaporates, setting up a complex weather system that includes, presumably, wind patterns.

But the probe had never spotted wind rippling the surface of Titan’s seas. They seemed as smooth as glass. That could be because the liquid hydrocarbons are more viscous than water and thus harder to get moving, or because the winds on Titan are simply not strong enough to blow the liquid into ripples. In 2010, Lorenz and others proposed that the winds would strengthen as Titan moved towards spring, allowing scientists a better chance to spot waves2. Saturn and its moons take about 29 Earth years to go around the Sun.

Four bright pixels

A spectrometer aboard Cassini took images of Punga Mare as the spacecraft flew past it several times during 2012 and 2013. Those images showed sunlight glinting off the ocean’s surface, as might be seen on Earth when an aeroplane flies low over a lake at dusk.

Four pixels in the images are brighter than one might expect from reflecting sunlight, Barnes reported at the conference. He concluded that they must represent something particularly rough on the surface — a wave or set of waves.

Calculations of the waves’ height suggested they were a puny few centimetres high. “Don’t make your surfing plane reservation for Titan just yet,” Barnes told the conference.

Knowing how the waves form will help scientists to better understand the physical conditions in Titan’s lakes and seas3. A NASA mission proposal, which was beaten by a proposal to return to Mars, would have sent a probe to float in one of Titan’s lakes. “If we drop a lake lander in there, is it going to splat instead of splash?” asks Barnes.

There is still a chance that Cassini is seeing reflections off a wet, solid surface, such as a mudflat, rather than actual waves. Future observations might spot the waves of Punga Mare again, but Barnes says that there is no guarantee that Cassini will pass by in the right position before the end of its mission, a planned plunge into Saturn in 2017.

A second report at the conference also hints at possible waves. Last summer, Cassini scientists spotted what they called a ‘magic island’ in another sea, Ligeia Mare, that appeared and then disappeared. It looked like a bright reflection in one image but was not visible 16 days later or in any photographs taken since, said Jason Hofgartner, a planetary scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

After ruling out possibilities such as an island exposed by a change in sea level, the team concluded that the ‘magic island’ is probably a set of waves, a group of bubbles rising from below the surface or a suspended mass, such as an iceberg.

The Ligeia Mare researchers may have better luck than Barnes and his colleagues — a Cassini fly-by in August should be able to image this particular area of Ligeia Mare and hunt for waves again.

Quelle: nature

.

Update: 21.03.2014

.

Surface of Titan Sea is mirror smooth, Stanford scientists find

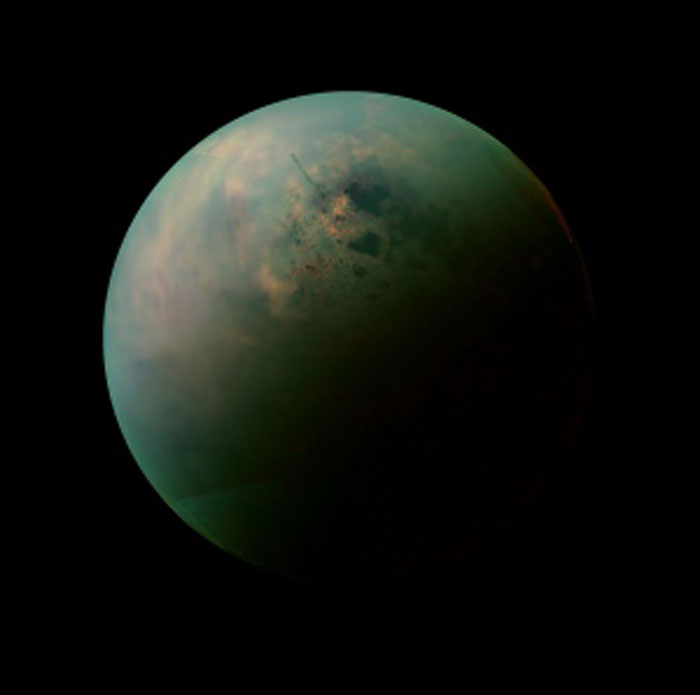

This false-color image of the surface of Titan was made using radar measurements made by NASA's Cassini spacecraft. The spacecraft revealed that the surface of Ligeia Mare, Titan's second largest lake, is unusually still, most likely due to a lack of winds at the time of observation.

.

New radar measurements of an enormous sea on Titan offer insights into the weather patterns and landscape composition of the Saturnian moon. The measurements, made in 2013 by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, reveal that the surface of Ligeia Mare, Titan's second largest sea, possesses a mirror-like smoothness, possibly due to a lack of winds.

"If you could look out on this sea, it would be really still. It would just be a totally glassy surface," said Howard Zebker, professor of geophysics and of electrical engineering at Stanford who is the lead author of a new study detailing the research.

The findings, recently published online in Geophysical Research Letters, also indicate that the solid terrain surrounding the sea is likely made of solid organic materials and not frozen water.

Saturn's second largest moon, Titan has a dense, planet-like atmosphere and large seas made of methane and ethane. Measuring roughly 260 miles (420 km) by 217 miles (350 km), Ligeia Mare is larger than Lake Superior on Earth. "Titan is the best analog that we have in the solar system to a body like the Earth because it is the only other body that we know of that has a complex cycle of solid, liquid, and gas constituents," Zebker said.

Titan's thick cloud cover makes it difficult for Cassini to obtain clear optical images of its surface, so scientists must rely on radar, which can see through the clouds, instead of a camera.

To paint a radar picture of Ligeia Mare, Cassini bounced radio waves off the sea's surface and then analyzed the echo. The strength of the reflected signal indicated how much wave action was happening on the sea. To understand why, Zebker said, imagine sunlight reflecting off of a lake on Earth. "If the lake were really flat, it would act as a perfect mirror and you would have an extremely bright image of the sun," he said. "But if you ruffle up the surface of the sea, the light gets scattered in a lot of directions, and the reflection would be much dimmer. We did the same thing with radar on Titan."

The radar measurements suggest the surface of Ligeia Mare is eerily still. "Cassini's radar sensitivity in this experiment is one millimeter, so that means if there are waves on Ligeia Mare, they're smaller than one millimeter. That's really, really smooth," Zebker said.

One possible explanation for the sea's calmness is that no winds happened to be blowing across that region of the moon when Cassini made its flyby. Another possibility is that a thin layer of some material is suppressing wave action. "For example, on Earth, if you put oil on top of a sea, you suppress a lot of small waves," Zebker said.

Cassini also measured microwave radiation emitted by the materials that make up Titan's surface. By analyzing those measurements, and accounting for factors such as temperature and pressure, Zebker's team confirmed previous findings that the terrain around Ligeia Mare is composed of solid organic material, likely the same methane and ethane that make up the sea. "Like water on Earth, methane on Titan can exists as a solid, a liquid, and a gas all at once," Zebker said.

Titan's similarities to Earth make it a good model for our own planet's early evolution, Zebker said. "Titan is different in the details from Earth, but because there is global circulation happening, the big picture is the same," he added. "Seeing something in two very different environments could help reveal the overall guiding principles for the evolution of planetary bodies, and help explain why Earth developed life and Titan didn't."

Quelle: EurekAlert

.

.

Cassini VIMS image showing specular reflections in one of Titan’s many lakes during the T85 flyby on July 24, 2012.

Quelle: NASA

5405 Views