The privately funded Fram2 mission is the first ever to take astronauts into polar orbit—and the latest sign of a “new normal” for human spaceflight

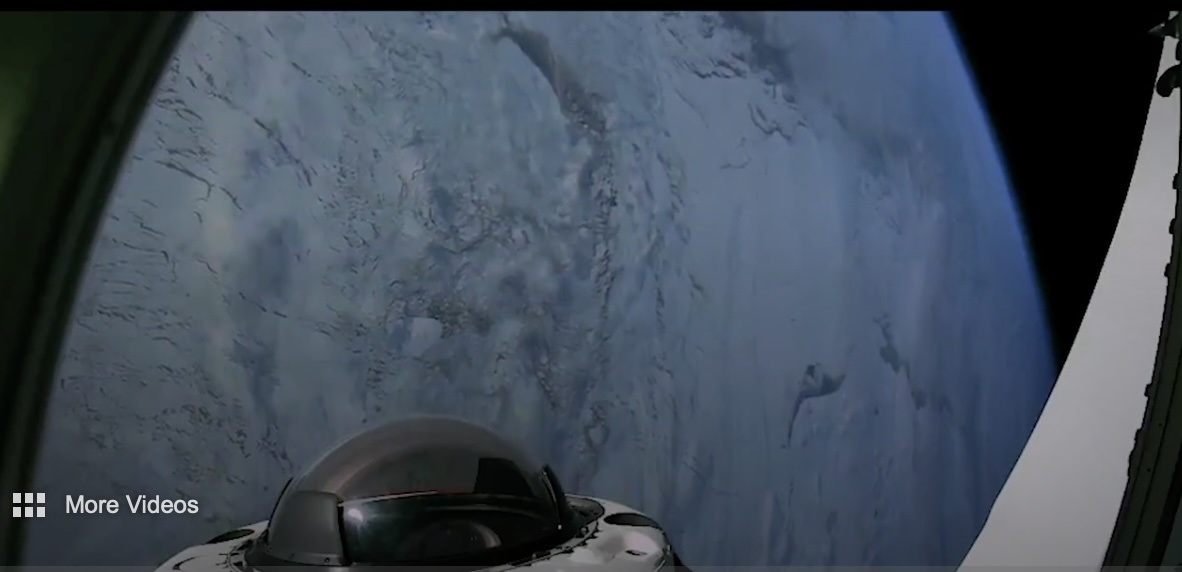

In some respects, the most notable thing about Fram2, the private four-person space mission that launched on Monday night on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, is its polar orbit. Named after the Norwegian polar-exploration vessel Fram, the Fram2 mission marks the first time humans have occupied this particular slot around our planet, a swooping ellipse that takes a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft between Earth’s North and South Poles in about 45 minutes. Especially when seen from a panoramic cupola attached to the spacecraft, the unique views offered by Fram2’s 430-kilometer-high orbital perch are breathtakingly cool—even leaving aside the vast expanses of polar ice far below.

But the notional noteworthiness of Fram2’s three-to-five-day stay in polar orbit ironically belies something even more remarkable: privately funded human spaceflight is now considered so routine that any such mission seeking to make headlines desperately needs some attention-grabbing “first.”

WHY DID FRAM2 GO TO POLAR ORBIT?

None of the 22 life-science-focused experiments carried onboard Fram2demanded that it reach polar orbit, which hadn’t been attempted in previous crewed missions because of the increased amount of fuel required to get there. (Fram2 flew southward from its launch site, whereas most space missions have targeted more equatorial orbits and have launched toward the east to receive a fuel-saving boost from Earth’s rotation). Simply put, aside from the desire for some novel gimmick, there was no clear rationale for SpaceX’s mission planners or Fram2’s leader, cryptocurrency billionaire Chun Wang, to have chosen a polar orbit in the first place.

WHY THIS MATTERS

None of this means that sending humans into that orbit isn’t a legitimately impressive feat. It is—all the more so because SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket not only safely delivered the Crew Dragon to polar orbit; it also had enough leftover fuel to still perform a pinpoint soft landing on an awaiting barge in the Atlantic Ocean. But Fram2’s “polarity” overshadows the more mundane but no less astonishing “new normal,” in which private human spaceflight has rapidly shifted from the stuff of science fiction to a decidedly unexceptional reality.

Consider that this is SpaceX’s 17th crewed mission, of which about a third have been privately funded. Wang and his three crewmates—filmmaker Jannicke Mikkelsen, roboticist Rabea Rogge and polar explorer Eric Philips—all rode in Resilience, the Crew Dragon vehicle that has flown three other crews (two of them private) to space. Resilience’s previous private missions were both commanded by billionaire entrepreneur Jared Isaacman, who has since parlayed his SpaceX-powered passion for spaceflight into a nomination to lead NASA on behalf of the Trump administration. And the Fram2 launch occurred scarcely two weeks after the liftoff of SpaceX’s NASA-funded Crew-10 mission to the International Space Station—the shortest gap yet between the company’s crewed launches, all of which have taken place as SpaceX has maintained a frenetic record-setting pace of uncrewed commercial launches and has continued the wildly ambitious development of its potentially revolutionary Starship vehicle.

WHAT’S NEXT

One might be tempted to think this is merely a reflection of SpaceX’s success, but the rising numbers of legitimate competitors for the company’s launch-industry dominance suggest otherwise. Even if SpaceX somehow falters, Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, United Launch Alliance and other launch providers all appear on track to offer broadly similar services in coming years, suggesting that this bold new era of spaceflight is here to stay.