25.03.2025

A team of researchers used the James Webb Space Telescope to uncover new details about SIMP 0136, a free-floating planet in the Milky Way that does not orbit a star.

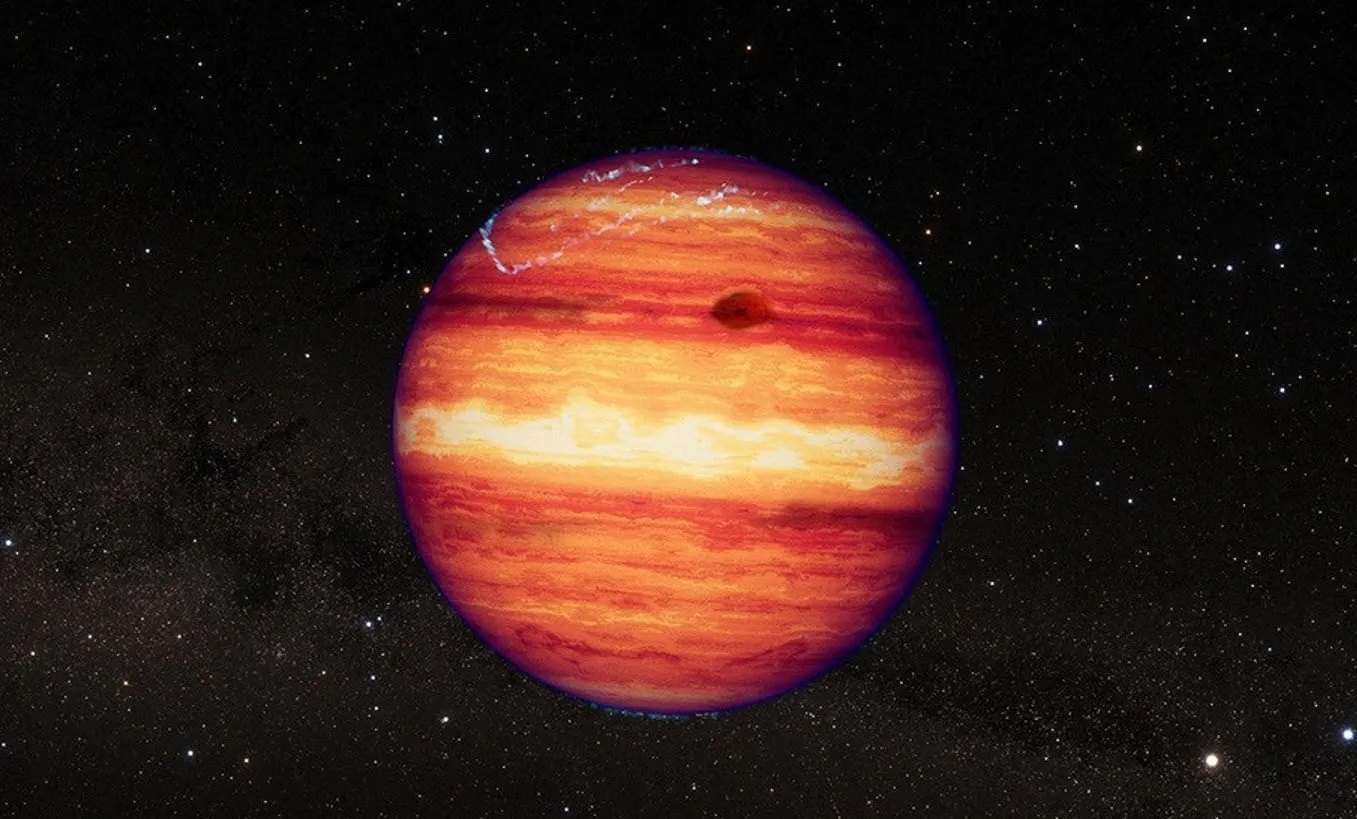

NOT EVERY LARGE object in space forms part of a solar system. There are some big objects that exist in isolation in space, without either being a star or orbiting one. One of these, SIMP 0136, wanders aimlessly in the Milky Way, about 20 light years away from Earth. It has a mass about 13 times that of Jupiter, and is thought to have the structure and chemical composition of a giant gas planet, though its true characteristics have not yet been determined.

Such untethered objects are typically classified either as “free-floating planets,” which form inside a star system, but are thrown out by the gravitational force of another planet, or as “brown dwarfs,” which form like stars in dense molecular clouds of gas and dust, but lack the mass to undergo stable nuclear fusion like a typical star (for this reason, brown dwarfs are sometimes also known as “failed stars”). It is unclear yet whether SIMP 0136 belongs to either of these categories.

To try to find out more about SIMP 0136’s characteristics, a team made up of researchers from Boston University and other institutions recently conducted detailed observations of the mysterious free-floating SIMP 0136 using the James Webb Space Telescope.

SIMP 0136 was an ideal target for research, for several reasons. Although difficult to observe using visible light, it shines brightly in infrared—in fact, SIMP 0136 is the brightest free-floating planetary-mass object in the northern sky. And because it is free-moving, observations of it aren’t affected by the light of nearby stars. On top of this, its rotation time is very short, about 2 hours and 40 minutes. This allows for efficient global observation of the planet.

The James Webb Space Telescope was selected for this work because of its excellent infrared observation capabilities. The team used two instruments that focus on different infrared wavelengths to look at the planet: the telescope’s Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) and its Mid Infrared Observatory (MIRI). The team used NIRSpec to observe the object for over three hours, enough to cover the entire planet's rotational period. Then, MIRI was used to observe for another rotation.

Previous observations had shown that SIMP 0136’s brightness varies, but the reason for this was unclear. So, the team analyzed new data gathered from the James Webb Space Telescope using an atmospheric model, and found that some wavelengths of infrared light recorded (shown in red in the diagram below) came from a cloud of evaporated iron molecules in the deepest layer of the planet’s atmosphere, while some other infrared wavelengths (shown in yellow below) came from a cloud of silicate mineral particles in the the planet’s upper atmosphere.

The unevenness of the state of each cloud layer is thought to be the reason why the brightness of SIMP 0136 changes as it rotates. It’s easy to understand if you think of Jupiter, which as a gas giant planet likely has a similar structure and chemical composition.

Or for another way to picture this, try imagining the surface of the Earth, says Philip Muirhead of Boston University, a coauthor of a new paper outlining these findings about SIMP 0136. “As the Earth rotates, when the ocean comes into view, you will observe stronger blue colors, and when you observe stronger brown or green colors, it means that continents, forest areas, et cetera come into view,” he explains.

In addition, the infrared light shown by the blue lines in the figure above comes from a high layer of SIMP 0136’s atmosphere, far above its cloud layers.

It is thought that the brightness of SIMP 0136, caused by these differences in infrared radiation, changes as it rotates because the temperature, like the cloud composition, varies from place to place on the planet. In addition, the researchers noticed hot spots where the planet’s infrared light was particularly bright. They believe that these may be caused by auroras, the existence of which has already been confirmed by radio wave observations.

However, it is difficult to explain all the changes in infrared brightness just by cloud and temperature variations. For this reason, the research team points out that there may be areas in SIMP 0136’s atmosphere where carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide are concentrated, and that these areas may also affect the infrared brightness as the planet rotates.

Quelle: WIRED