25.03.2025

A new spin on decades of W. M. Keck Observatory research

Maunakea, Hawaiʻi – A recent study reveals the famous Wolf-Rayet 104 “pinwheel star” holds more mystery but is even less likely to be the potential ‘Death Star’ it was once thought to be.

Research by W. M. Keck Observatory Instrument Scientist and astronomer Grant Hill finally confirms what has been suspected for years: WR 104 has at its heart a pair of massive stars orbiting each other with a period of about 8 months and the collision between their powerful winds gives rise to its rotating pinwheel of dust that glows in the infrared, and spins with the same period.

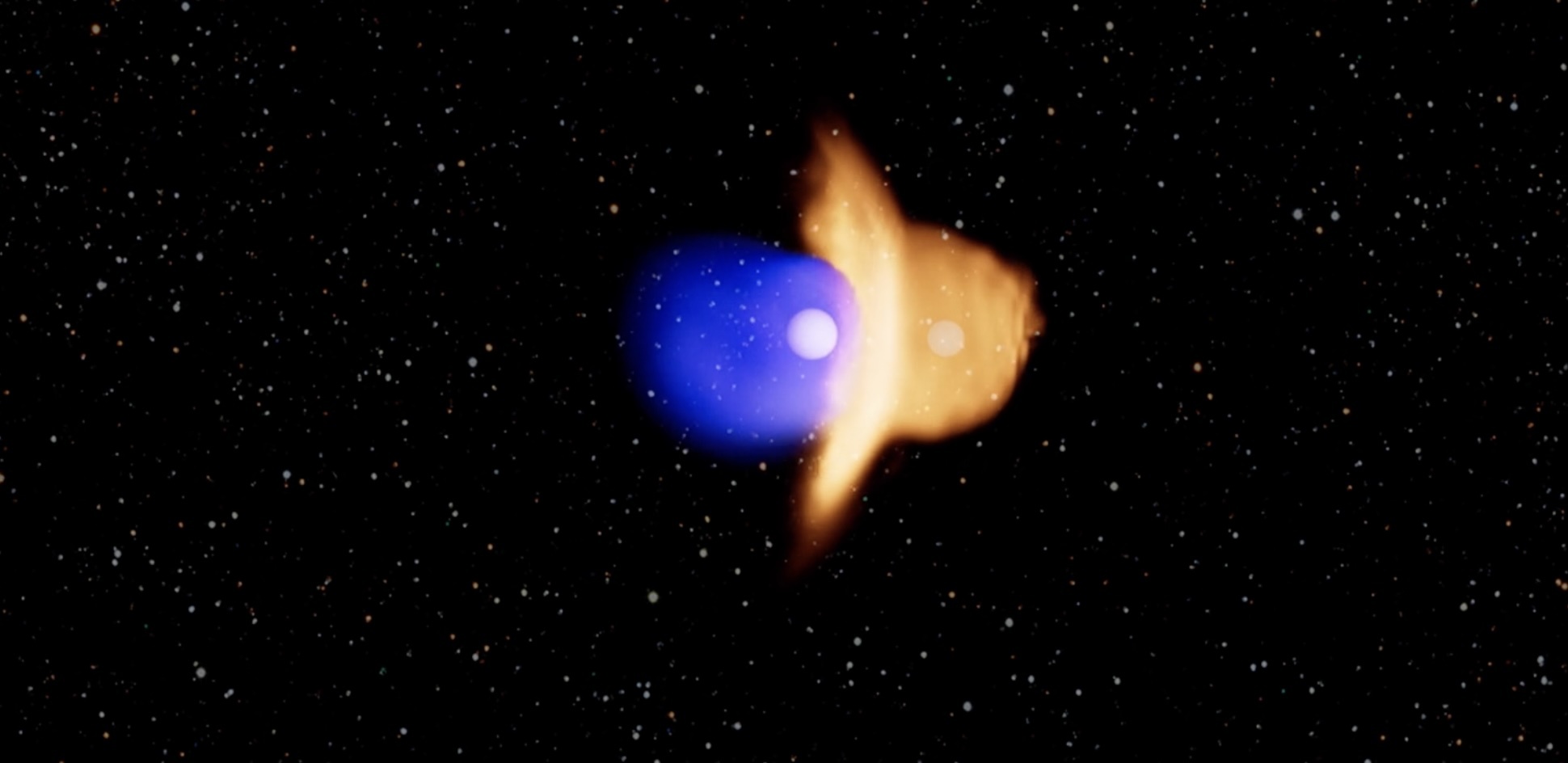

An artist’s animation of WR 104, first discovered at Keck Observatory in 1999. It consists of two stars orbiting each other; a Wolf-Rayet star that produces a powerful, carbon-rich wind (depicted in yellow), and an OB star that creates a wind mostly made of hydrogen (depicted in blue). When the winds collide, they whip up a hydrocarbon “dust” spiral. Credit: W. M. Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko

The pinwheel structure of WR 104 was discovered at Keck Observatory in 1999 and the remarkable images of it turning in the sky astonished astronomers. One of the two stars that were suspected to orbit each other – a Wolf-Rayet star– is a massive, evolved star that produces a powerful wind highly enriched with carbon. The second star – a less evolved but even more massive OB star – has a strong wind that is still mostly hydrogen. Collisions between winds like these are thought to allow hydrocarbons to form, often referred to as “dust” by astronomers. When discovered, WR 104 also made headlines as a potential gamma-ray burst (GRB) that could be aimed right at us. Models of the pinwheel images indicated it was rotating in the plane of the sky as if we were looking directly down on someone spinning a streaming garden hose over their head. That could mean the rotational poles of the two stars might be pointed in our direction as well. When one of the stars ends its life as a supernova the explosion might be energetic enough to create a GRB that would beam in the polar directions. Since it is located right here in our own Galaxy, and seemed to be aimed right at us, at the time, WR 104 gained a second nickname – the ‘Death Star’.

Hill’s research, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, is based on spectroscopy using three of Keck Observatory’s instruments – the Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS), the Echellette Spectrograph and Imager (ESI), and the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSPEC). With these spectra, he was able to measure velocities for the two stars, calculate their orbit and identify features in the spectra arising from the colliding winds. There turned out to be a very big surprise in store though.

“Our view of the pinwheel dust spiral from Earth absolutely looks face-on (spinning in the plane of the sky), and it seemed like a pretty safe assumption that the two stars are orbiting the same way” says Hill. “When I started this project, I thought the main focus would be the colliding winds and a face-on orbit was a given. Instead, I found something very unexpected. The orbit is tilted at least 30 or 40 degrees out of the plane of the sky.”

While a relief for those worried about a nearby GRB pointed right at us, this represents a real curveball. How can the dust spiral and the orbit be tilted so much to each other? Are there more physics that needs to be considered when modelling the formation of the dust plume?

“This is such a great example of how with astronomy we often begin a study and the universe surprises us with mysteries we didn’t expect” muses Hill. “We may answer some questions but create more. In the end, that is sometimes how we learn more about physics and the universe we live in. In this case, WR 104 is not done surprising us yet!”

ABOUT NIRSPEC

The Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSPEC) is a unique, cross-dispersed echelle spectrograph that captures spectra of objects over a large range of infrared wavelengths at high spectral resolution. Built at the UCLA Infrared Laboratory by a team led by Prof. Ian McLean, the instrument is used for radial velocity studies of cool stars, abundance measurements of stars and their environs, planetary science, and many other scientific programs. A second mode provides low spectral resolution but high sensitivity and is popular for studies of distant galaxies and very cool low-mass stars. NIRSPEC can also be used with Keck II’s adaptive optics (AO)system to combine the powers of the high spatial resolution of AO with the high spectral resolution of NIRSPEC. Support for this project was provided by theHeising-Simons Foundation.

ABOUT LRIS

The Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS) is a very versatile and ultra-sensitive visible-wavelength imager and spectrograph built at the California Institute of Technology by a team led by Prof. Bev Oke and Prof. Judy Cohen and commissioned in 1993. Since then it has seen two major upgrades to further enhance its capabilities: the addition of a second, blue arm optimized for shorter wavelengths of light and the installation of detectors that are much more sensitive at the longest (red) wavelengths. Each arm is optimized for the wavelengths it covers. This large range of wavelength coverage, combined with the instrument’s high sensitivity, allows the study of everything from comets (which have interesting features in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum), to the blue light from star formation, to the red light of very distant objects. LRIS also records the spectra of up to 50 objects simultaneously, especially useful for studies of clusters of galaxies in the most distant reaches, and earliest times, of the universe. LRIS was used in observing distant supernovae by astronomers who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011 for research determining that the universe was speeding up in its expansion.

ABOUT ESI

The Echellette Spectrograph and Imager (ESI) is a medium-resolution visible-light spectrograph that records spectra from 0.39 to 1.1 microns in each exposure. Built at UCO/Lick Observatory by a team led by Prof. Joe Miller, ESI also has a low-resolution mode and can image in a 2 x 8 arc min field of view. An upgrade provided an integral field unit that can provide spectra everywhere across a small, 5.7 x4.0 arc sec field. Astronomers have found a number of uses for ESI, from observing the cosmological effects of weak gravitational lensing to searching for the most metal-poor stars in our galaxy.

Quelle: W. M. Keck Observatory