21.03.2025

Physicists had long assumed that the elusive force has constant strength. But the latest results from a project to map the Universe’s expansion challenge this idea.

Part of the DESI telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona.Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/P. Marenfeld

Fresh data have bolstered the discovery that dark energy, the mysterious force that makes galaxies accelerate away from each other, has weakened over the past 4.5 billion years.

The effect was first tentatively reported in April last year, but the latest results — presented on 19 March by the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) collaboration at a meeting of the American Physical Society in Anaheim, California — are based on three years’ worth of data-taking, versus one year for the results announced in 2024.

“Now I’m really sitting up and paying attention,” says Catherine Heymans, an astronomer at the University of Edinburgh, UK, and the Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

If the findings hold up, they could force cosmologists to revise their ‘standard model’ for the history of the Universe. The model has generally assumed that dark energy is an inherent property of empty space that does not change over time — a ‘cosmological constant’.

“The gauntlet has been thrown down to the physicists to explain this,” says Heymans.

Cosmic mapping

The DESI telescope is located at Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona. It uses 5,000 robotic arms to point optical fibres at selected points where galaxies or quasars are located within its field of view. The fibres then deliver light to sensitive spectrographs that measure how much each object is redshifted — meaning the degree to which its light waves were stretched by the expansion of space on their way to Earth. Researchers can estimate an object’s distance using its redshift, to produce a 3D map of the Universe’s expansion history.

In that map, researchers then look at the density of galaxies to identify variations that are left over from sound waves called baryon acoustic oscillations (BAOs), which existed before stars began to form. Those variations have a characteristic scale that started out at 150 kiloparsecs (450,000 light years) in the primordial Universe and has been increasing with the cosmic expansion; they have now grown by a factor of 1,000 to 150 megaparsecs across — making them the largest known features in the current Universe.

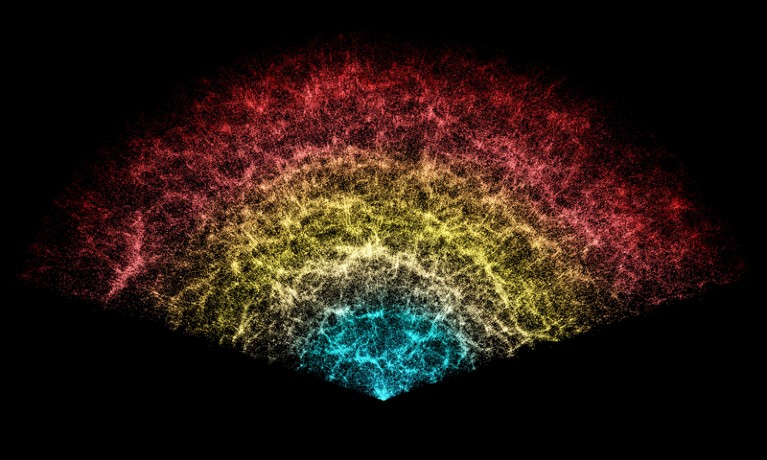

A slice of the 3D map of galaxies based on data collected by DESI in the first year of its survey. Credit: DESI Collaboration/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Proctor

Quelle: nature

+++

Is dark energy destined to dominate the universe and lead to the ‘big crunch’?

New universes may emerge in due course, says scientist at Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument in Arizona

Since the big bang, a cosmic battle has been under way between matter (both dark matter and ordinary) and dark energy.

The gravitational force that draws massive objects such as galaxies towards each other works against the expansion of the universe. But astronomical observations show that the universe’s expansion has, oddly, been speeding up. This led scientists to conclude that dark energy, a mysterious force acting as a sort of anti-gravity, permeates the entirety of space. And dark energy appeared to be at a significant advantage in the cosmic tug of war.

As space expands, matter becomes more spread out, so its influence weakens. By contrast, dark energy is thought to be a property of space itself. So as space expands, it is constantly filled up with more dark energy, so its strength remains constant and it becomes the runaway winner. That, at least, has been the prediction of the most widely accepted theoretical model of recent decades.

“Eventually you have this picture where more distant regions are receding from us faster than light and they become, in principle, untouchable. That loss of contact grows and grows until even the most nearby current galaxies are too far away,” said Prof John Peacock, a cosmologist at the University of Edinburgh and a collaborator with the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument(Desi), based in Arizona. “It ends in an awful loneliness where we are left isolated because everything is being whisked away too fast.”

This “big freeze” scenario is predicted by the current leading theoretical model of the universe, which has assumed dark energy to be constant and which suggests that dark energy accounts for 70% of the content of the universe, with dark matter comprising 25% and ordinary matter just 5%.

The most recent Desi results present the latest in a series of challenges to this picture. Measurements of 15m galaxies spanning 11bn years of cosmic history reveal patterns that scientists say are most readily interpreted as the result of dark energy that has evolved over time.

The data is best explained, according to the Desi analysis, if dark energy peaked when the universe was about 70% of its current age and is now on the decline. If confirmed, this reopens the question of whether dark energy is destined to dominate the fate of the universe.

If dark energy were, in future, to decline beyond zero and become negative (effectively switching teams and joining forces with gravity) the expansion could be sent into reverse, resulting in an ultimate “big crunch”.

“We could be back to one of those comforting old solutions where the universe might recollapse – and perhaps start again,” said Prof Carlos Frenk, a cosmologist at Durham University and a Desi team member. “I was always disturbed by a universe that keeps expanding forever … to become a dark, frozen expanse. I’m much more at ease with the possibility of new universes emerging in due course.”

But this is just one of a series of possibilities. If dark energy declined to zero and settled there, expansion would continue and the universe would have a quieter ending, in which galaxies remain in view until stars run out of fuel and flicker out of existence.

“The fate of the universe depends on what the dark energy does in the future,” said Peacock. “For things to recollapse it would have to change its actual sign. In principle, it could. Whether it’s going to, we have no idea.”

Quelle: The Guardian