24.02.2025

Summary

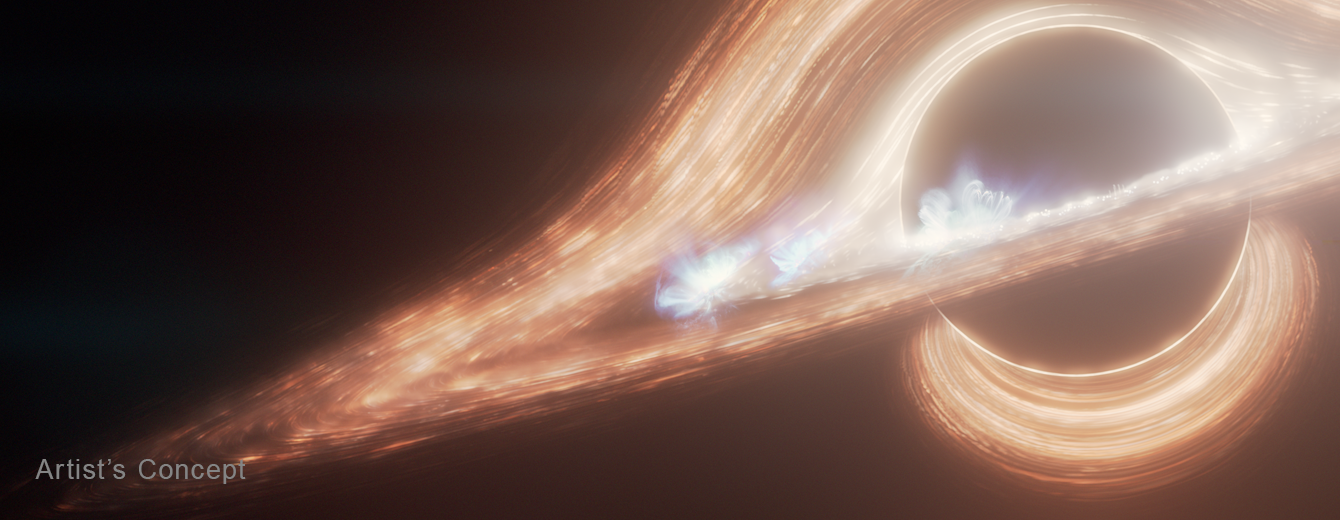

Observations revealed ongoing fireworks featuring short bursts and longer flares.

Imagine solar flares, but on a mind-boggling scale. A constant scintillation that is bright enough to shine across 26,000 light-years of space. And interspersed between the flickers, brilliant flashes that spew out on a daily basis.

Researchers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have spotted this activity in the center of our galaxy. The source is the accretion disk around the Milky Way’s central supermassive black hole. Webb detected brightness changes over remarkably short timescales, meaning they are coming from the black hole’s inner disk, not far beyond its event horizon.

The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way appears to be having a party, complete with a disco ball-style light show. Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, a team of astrophysicists has gained the longest, most detailed glimpse yet of the “void” that lurks in the middle of our galaxy.

They found that the swirling disk of gas and dust (or accretion disk) orbiting the central supermassive black hole, called Sagittarius A*, is emitting a constant stream of flares with no periods of rest. The level of activity occurs over a wide range of time — from short interludes to long stretches. While some flares are faint flickers, lasting mere seconds, other flares are blindingly bright eruptions, which spew daily. There also are even fainter changes that surge over months.

The new findings could help physicists better understand the fundamental nature of black holes, how they get fed from their surrounding environments, and the dynamics and evolution of our own galaxy.

The study published in the Feb. 18 issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“In our data, we saw constantly changing, bubbling brightness,” said Farhad Yusef-Zadeh of Northwestern University in Illinois, who led the study. “And then boom! A big burst of brightness suddenly popped up. Then, it calmed down again. We couldn’t find a pattern in this activity. It appears to be random. The activity profile of this black hole was new and exciting every time that we looked at it.”

Random Fireworks

To conduct the study, Yusef-Zadeh and his team used Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) to observe Sagittarius A* for a total of 48 hours in 8- to 10-hour increments across one year. This enabled them to track how the black hole changed over time.

While the team expected to see flares, Sagittarius A* was more active than they anticipated. The observations revealed ongoing fireworks of various brightnesses and durations. The accretion disk surrounding the black hole generated five to six big flares per day and several small sub-flares or bursts in between.

Two Separate Processes at Play

Although astrophysicists do not yet fully understand the processes at play, Yusef-Zadeh suspects two separate processes are responsible for the short bursts and longer flares. He posits that minor disturbances within the accretion disk likely generate the faint flickers. Specifically, turbulent fluctuations within the disk can compress plasma (a hot, electrically charged gas) to cause a temporary burst of radiation. Yusef-Zadeh likens these events to solar flares.

“It’s similar to how the Sun’s magnetic field gathers together, compresses, and then erupts a solar flare,” he explained. “Of course, the processes are more dramatic because the environment around a black hole is much more energetic and much more extreme. But the Sun’s surface also bubbles with activity.”

Yusef-Zadeh attributes the big, bright flares to occasional magnetic reconnection events — a process where two magnetic fields collide, releasing energy in the form of accelerated particles. Traveling at velocities near the speed of light, these particles emit bright bursts of radiation.

“A magnetic reconnection event is like a spark of static electricity, which, in a sense, also is an ‘electric reconnection,’” Yusef-Zadeh said.

Dual ‘Vision’

Because Webb’s NIRCam can observe two separate wavelengths at the same time (2.1 and 4.8 microns in the case of these observations), Yusef-Zadeh and his collaborators were able to compare how the flares’ brightness changed with each wavelength. Yet again, the researchers were met with a surprise. They discovered events observed at the shorter wavelength changed brightness slightly before the longer-wavelength events.

“This is the first time we have seen a time delay in measurements at these wavelengths,” Yusef-Zadeh said. “We observed these wavelengths simultaneously with NIRCam and noticed the longer wavelength lags behind the shorter one by a very small amount — maybe a few seconds to 40 seconds.”

This time delay provided more clues about the physical processes occurring around the black hole. One explanation is that the particles lose energy over the course of the flare — losing energy quicker at shorter wavelengths than at longer wavelengths. Such changes are expected for particles spiraling around magnetic field lines.

Aiming for an Uninterrupted Look

To further explore these questions, Yusef-Zadeh and his team hope to use Webb to observe Sagittarius A* for a longer period of time, such as 24 uninterrupted hours, to help reduce noise and enable the researchers to see even finer details.

“When you are looking at such weak flaring events, you have to compete with noise,” Yusef-Zadeh said. “If we can observe for 24 hours, then we can reduce the noise to see features that we were unable to see before. That would be amazing. We also can see if these flares repeat themselves or if they are truly random.”

The James Webb Space Telescope is the world’s premier space science observatory. Webb is solving mysteries in our solar system, looking beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probing the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and CSA (Canadian Space Agency).

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 27.02.2025

.

JWST provides insights into rare ultra-hot Neptune LTT 9779 b

A team of international researchers including Dr Jake Taylor from the Department of Physics at the University of Oxford, has used the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to explore the exotic atmosphere of LTT 9779 b, a rare ‘ultra-hot Neptune’. The results have been published today (25 February) in a compelling new study in Nature Astronomy.

The study offers new insights into the extreme weather patterns and atmospheric properties of this fascinating exoplanet, LTT 9779 b, that resides in the so-called hot Neptune desert, a category of planets where exceptionally few are known to exist. While giant planets orbiting very close to their host stars – often called hot Jupiters – are commonly detected using current exoplanet-finding methods, ultra-hot Neptunes like LTT 9779 b remain remarkably rare.

‘Finding a planet of this size so close to its host star is like finding a snowball that hasn’t melted in a fire,’ says graduate student Louis-Philippe Coulombe from the Université de Montréal's Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets (IREx) who led the study. ‘It’s a testament to the diversity of planetary systems and offers a window into how planets evolve under extreme conditions.’

A unique laboratory for alien weather

Orbiting its host star in less than a day, LTT 9779 b is subjected to searing temperatures reaching almost 2,000°C on its dayside. The planet is tidally locked (similar to Earth’s Moon), meaning one side constantly faces its star while the other remains in perpetual darkness. Despite such extremes, the team discovered that the planet’s dayside hosts reflective clouds on its cooler western hemisphere, creating a striking contrast to the hotter eastern side. ‘This planet provides a unique laboratory to understand how clouds and the transport of heat interact in the atmospheres of highly irradiated worlds,’ says Coulombe.

Dr Taylor from the University of Oxford worked alongside Coulombe in analysing the data. The pair had previously performed an initial atmospheric analysis of the planet’s spectrum, the results of which were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters in 2024: ‘Our original study of the transmission spectrum hinted at the need for high altitude clouds to explain the observations; our latest study confirms the existence of these clouds,’ he explains.

The team’s analysis, conducted using JWST as part of the NEAT (NIRISS Exploration of Atmospheric Diversity of Transiting Exoplanets) Guaranteed Time Observation programme, uncovered an asymmetry in the planet’s dayside reflectivity. The team proposed that the uneven distribution of heat and clouds is driven by powerful winds that transport heat around the planet. These findings help refine models describing how heat is transported across a planet and cloud formation in exoplanet atmospheres, helping bridge the gap between theory and observation.

Mapping the atmosphere of an ultra-hot Neptune

The research team studied the atmosphere in detail by analysing both the heat emitted by the planet and the light it reflects from its star. To create a clearer picture, they observed the planet at multiple positions in its orbit and analysed its properties at each phase individually. They discovered clouds made of materials like silicate minerals, which form on the slightly cooler western side of the planet’s dayside. These reflective clouds help explain why this planet is so bright at visible wavelengths, bouncing back much of the star’s light.

By combining this reflected light with heat emissions, the team was able to create a detailed model of the planet’s atmosphere. Their findings reveal a delicate balance between intense heat from the star and the planet’s ability to redistribute energy. The study also detected water vapour in the atmosphere, providing important clues about the planet's composition and the processes that govern its extreme environment.

‘By modelling LTT 9779 b’s atmosphere in detail, we’re starting to unlock the processes driving its alien weather patterns,’ explains Professor Björn Benneke, a co-author of the study and Coulombe’s research advisor.

Implications for exoplanet science

This rare planetary system continues to challenge scientists’ understanding of how planets form, migrate, and endure in the face of unrelenting stellar forces. The planet’s reflective clouds and high metallicity may shed light on how atmospheres evolve in extreme environments. LTT 9779 b is a remarkable laboratory for exploring these questions, offering insights into the broader processes that shape the architecture of planetary systems across the galaxy.

‘These findings give us a new lens for understanding atmospheric dynamics on smaller gas giants,’ says Coulombe. ‘This is just the beginning of what JWST will reveal about these fascinating worlds.’

Other instruments are also being used to comprehensively study these rare planetary systems: ‘We haven’t finished piecing together the information about this planet yet,’ concludes Dr Taylor. ‘We are currently using observations from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Very Large Telescope to study the dayside cloud structure in more detail to learn as much as possible.’

Quelle: AAAS

----

Update: 5.03.2025

.

NASA’s Webb Exposes Complex Atmosphere of Starless Super-Jupiter

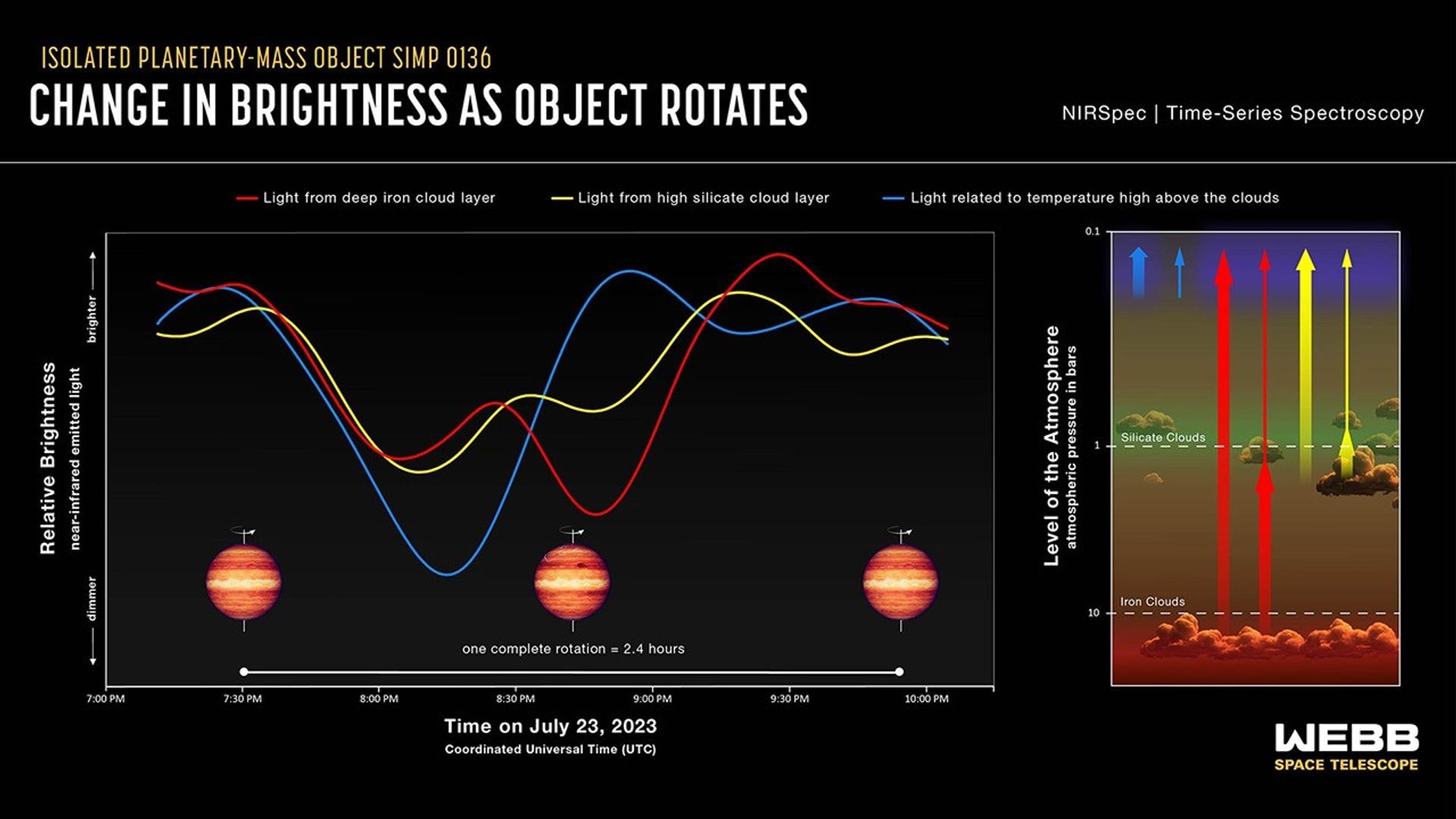

An international team of researchers has discovered that previously observed variations in brightness of a free-floating planetary-mass object known as SIMP 0136 must be the result of a complex combination of atmospheric factors, and cannot be explained by clouds alone.

Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to monitor a broad spectrum of infrared light emitted over two full rotation periods by SIMP 0136, the team was able to detect variations in cloud layers, temperature, and carbon chemistry that were previously hidden from view.

The results provide crucial insight into the three-dimensional complexity of gas giant atmospheres within and beyond our solar system. Detailed characterization of objects like these is essential preparation for direct imaging of exoplanets, planets outside our solar system, with NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which is scheduled to begin operations in 2027.

Rapidly Rotating, Free-Floating

SIMP 0136 is a rapidly rotating, free-floating object roughly 13 times the mass of Jupiter, located in the Milky Way just 20 light-years from Earth. Although it is not classified as a gas giant exoplanet — it doesn’t orbit a star and may instead be a brown dwarf — SIMP 0136 is an ideal target for exo-meteorology: It is the brightest object of its kind in the northern sky. Because it is isolated, it can be observed with no fear of light contamination or variability caused by a host star. And its short rotation period of just 2.4 hours makes it possible to survey very efficiently.

Prior to the Webb observations, SIMP 0136 had been studied extensively using ground-based observatories and NASA’s Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes.

“We already knew that it varies in brightness, and we were confident that there are patchy cloud layers that rotate in and out of view and evolve over time,” explained Allison McCarthy, doctoral student at Boston University and lead author on a study published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. “We also thought there could be temperature variations, chemical reactions, and possibly some effects of auroral activity affecting the brightness, but we weren’t sure.”

To figure it out, the team needed Webb’s ability to measure very precise changes in brightness over a broad range of wavelengths.

Charting Thousands of Infrared Rainbows

Using NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph), Webb captured thousands of individual 0.6- to 5.3-micron spectra — one every 1.8 seconds over more than three hours as the object completed one full rotation. This was immediately followed by an observation with MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument), which collected hundreds of spectroscopic measurements of 5- to 14-micron light — one every 19.2 seconds, over another rotation.

The result was hundreds of detailed light curves, each showing the change in brightness of a very precise wavelength (color) as different sides of the object rotated into view.

“To see the full spectrum of this object change over the course of minutes was incredible,” said principal investigator Johanna Vos, from Trinity College Dublin. “Until now, we only had a little slice of the near-infrared spectrum from Hubble, and a few brightness measurements from Spitzer.”

The team noticed almost immediately that there were several distinct light-curve shapes. At any given time, some wavelengths were growing brighter, while others were becoming dimmer or not changing much at all. A number of different factors must be affecting the brightness variations.

“Imagine watching Earth from far away. If you were to look at each color separately, you would see different patterns that tell you something about its surface and atmosphere, even if you couldn’t make out the individual features,” explained co-author Philip Muirhead, also from Boston University. “Blue would increase as oceans rotate into view. Changes in brown and green would tell you something about soil and vegetation.”

Patchy Clouds, Hot Spots, and Carbon Chemistry

To figure out what could be causing the variability on SIMP 0136, the team used atmospheric models to show where in the atmosphere each wavelength of light was originating.

“Different wavelengths provide information about different depths in the atmosphere,” explained McCarthy. “We started to realize that the wavelengths that had the most similar light-curve shapes also probed the same depths, which reinforced this idea that they must be caused by the same mechanism.”

One group of wavelengths, for example, originates deep in the atmosphere where there could be patchy clouds made of iron particles. A second group comes from higher clouds thought to be made of tiny grains of silicate minerals. The variations in both of these light curves are related to patchiness of the cloud layers.

A third group of wavelengths originates at very high altitude, far above the clouds, and seems to track temperature. Bright “hot spots” could be related to auroras that were previously detected at radio wavelengths, or to upwelling of hot gas from deeper in the atmosphere.

Some of the light curves cannot be explained by either clouds or temperature, but instead show variations related to atmospheric carbon chemistry. There could be pockets of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide rotating in and out of view, or chemical reactions causing the atmosphere to change over time.

“We haven’t really figured out the chemistry part of the puzzle yet,” said Vos. “But these results are really exciting because they are showing us that the abundances of molecules like methane and carbon dioxide could change from place to place and over time. If we are looking at an exoplanet and can get only one measurement, we need to consider that it might not be representative of the entire planet.”

This research was conducted as part of Webb’s General Observer Program 3548.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 6.03.2025

.

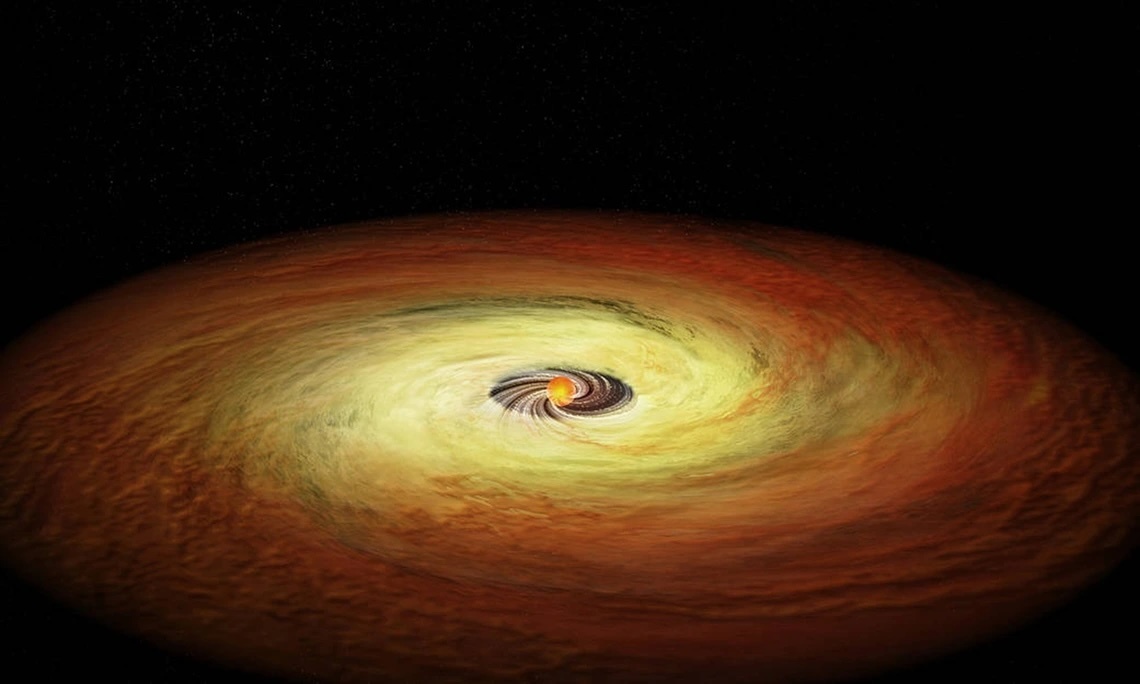

James Webb Telescope reveals planet-forming disks can last longer than previously thought

This illustration shows a lower mass star surrounded by its planet-forming disk of gas and dust. The planet formation process would cause gaps, not shown in this illustration, to appear in the disk. The streams near the center show how matter from the disk is still falling onto the star.

NASA/CXC/M. Weiss

If there were such a thing as a photo album of the universe, it might include snapshots of pancake-like disks of gas and dust, swirling around newly formed stars across the Milky Way. Known as planet-forming disks, they are believed to be a short-lived feature around most, if not all, young stars, providing the raw materials for planets to form.

Most of these planetary nurseries are short-lived, typically lasting only about 10 million years – a fleeting existence by cosmic standards. Now, in a surprising find, researchers at the University of Arizona have discovered that disks can grace their host stars much longer than previously thought, provided the stars are small – one-tenth of the sun's mass or less.

In a paper published in the Astrophysical Letters Journal, a research team led by Feng Long of the U of A Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, in the College of Science, reports a detailed observation of a protoplanetary disk at the ripe old age of 30 million years. Presenting the first detailed chemical analysis of a long-lived disk using NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, the paper provides new insights into planet formation and the habitability of planets outside our solar system.

"In a sense, protoplanetary disks provide us with baby pictures of planetary systems, including a glimpse of what our solar system may have looked like in its infancy," said Long, the paper's lead author and a Sagan Fellow with the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

As long as the star has a certain mass, high-energy radiation from the young star blows the gas and dust out of the disk, and it can no longer serve as raw material to build planets, Long explained.

The team observed a star with the official designation WISE J044634.16–262756.1B – more conveniently known as J0446B – located in the constellation Columba (Latin for "dove") about 267 light-years from Earth. The researchers found that its planet-forming disk has lasted about three times longer than expected.

"Although we know that most disks disperse within 10 million to 20 million years, we are finding that for specific types of stars, their disks can last much longer," Long said. "Because materials in the disk provide the raw materials for planets, the disk's lifespan determines how much time the system has to form planets."

Even though tiny stars retain their disks longer, their disk's chemical makeup does not change significantly. The similar chemical composition regardless of age indicates that the chemistry does not change drastically even as a disk reaches an advanced age. Such a long-lived, stable chemical environment could provide planets around low-mass stars with more time to form.

By analyzing the disk's gas content, the researchers ruled out the possibility that the disk around J0446B is a so-called debris disk, a longer-lasting type of disk that consists of second-generation material produced by collisions of asteroid-like bodies.

"We detected gases like hydrogen and neon, which tells us that there is still primordial gas left in the disk around J0446B," said Chengyan Xie, a doctoral student at LPL who also contributed to the study.

The confirmed existence of long-lived disks rich in gases has implications for life outside our solar system, according to the authors. Of particular interest to researchers is the TRAPPIST-1 system, located 40 light-years from Earth, consisting of a red dwarf star and seven planets similar in size to Earth. Three of those planets are located in the "habitable zone," where conditions allow for liquid water to exist and offer the potential for life to form, at least in principle.

Because stars with long-lived planetary disks fall into a similar mass category as the central star in the TRAPPIST-1 system, the existence of long-lived disks is especially interesting for the evolution of planetary systems, say Long and her co-authors.

"To make the specific arrangement of orbits we see with TRAPPIST-1, planets need to migrate inside the disk, a process that requires the presence of gas," said Ilaria Pascucci, a professor of planetary sciences at LPL who co-authored the study. "The long presence of gas we find in those disks might be the reason behind TRAPPIST-1's unique arrangement."

Long-lived disks have not been found for high-mass stars such as the sun, since stars in such systems evolve much more quickly and planets have less time to form. Although our solar system took a different evolutionary route, long-lived disks can tell researchers a lot about the universe, the authors noted, because low-mass stars are believed to vastly outnumber sun-like stars.

"Developing a better understanding of how low-mass star systems evolve and getting snapshots of long-lived disks might help pave the way to filling out the blanks in the photo album of the universe," Long said.

Quelle: The University of Arizona

----

Update: 19.03.2025

.

NASA’s Webb Images Young, Giant Exoplanets, Detects Carbon Dioxide

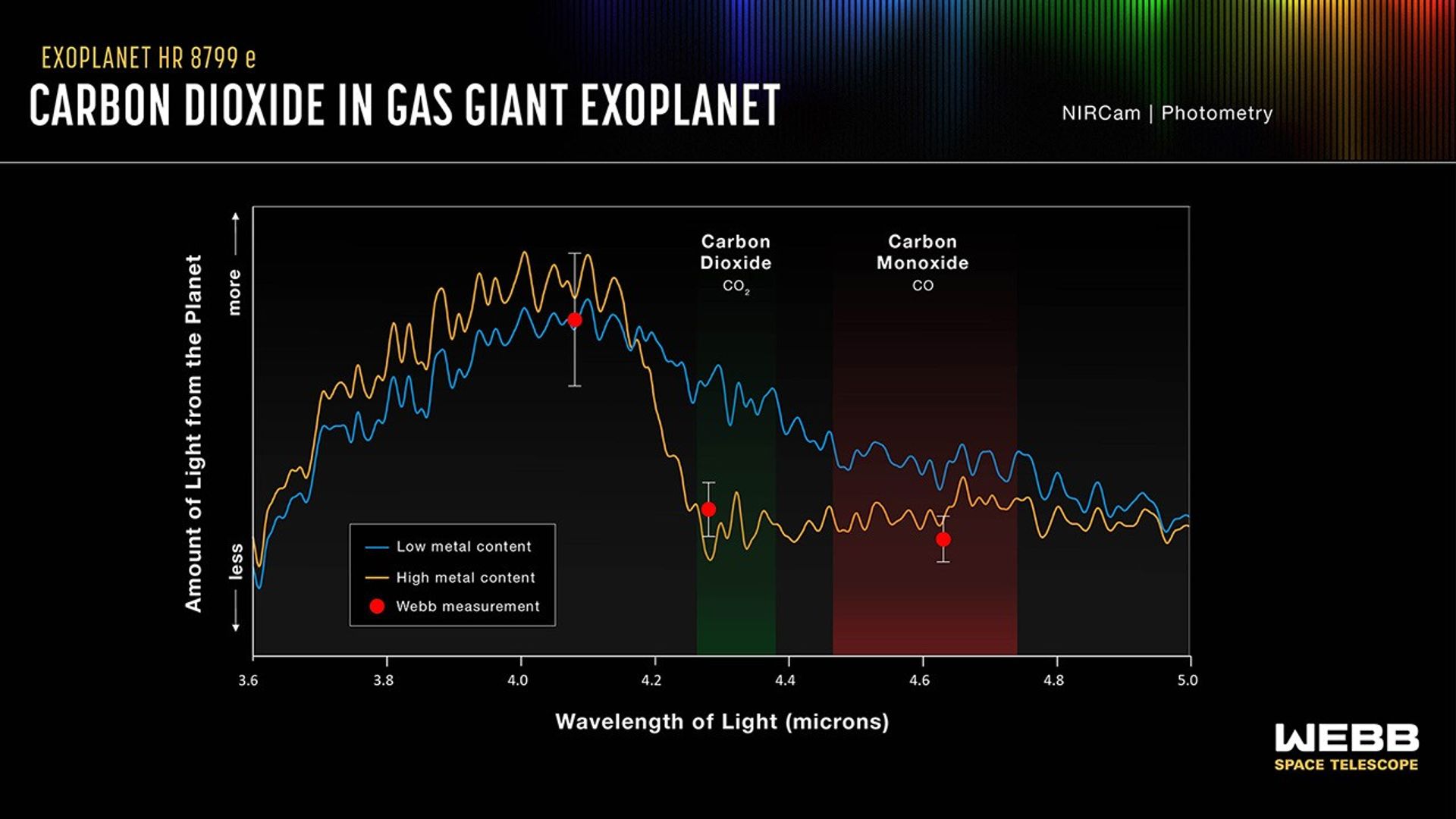

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has captured direct images of multiple gas giant planets within an iconic planetary system. HR 8799, a young system 130 light-years away, has long been a key target for planet formation studies.

The observations indicate that the well-studied planets of HR 8799 are rich in carbon dioxide gas. This provides strong evidence that the system’s four giant planets formed much like Jupiter and Saturn, by slowly building solid cores that attract gas from within a protoplanetary disk, a process known as core accretion.

The results also confirm that Webb can infer the chemistry of exoplanet atmospheres through imaging. This technique complements Webb’s powerful spectroscopic instruments, which can resolve the atmospheric composition.

“By spotting these strong carbon dioxide features, we have shown there is a sizable fraction of heavier elements, like carbon, oxygen, and iron, in these planets’ atmospheres,” said William Balmer, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “Given what we know about the star they orbit, that likely indicates they formed via core accretion, which is an exciting conclusion for planets that we can directly see.”

Balmer is the lead author of the study announcing the results published today in The Astrophysical Journal. Balmer and their team’s analysis also includes Webb’s observation of a system 97 light-years away called 51 Eridani.

Image A: HR 8799 (NIRCam Image)

Image B: 51 Eridani (NIRCam Image)

HR 8799 is a young system about 30 million years old, a fraction of our solar system’s 4.6 billion years. Still hot from their tumultuous formation, the planets within HR 8799 emit large amounts of infrared light that give scientists valuable data on how they formed.

Giant planets can take shape in two ways: by slowly building solid cores with heavier elements that attract gas, just like the giants in our solar system, or when particles of gas rapidly coalesce into massive objects from a young star’s cooling disk, which is made mostly of the same kind of material as the star. The first process is called core accretion, and the second is called disk instability. Knowing which formation model is more common can give scientists clues to distinguish between the types of planets they find in other systems.

“Our hope with this kind of research is to understand our own solar system, life, and ourselves in the comparison to other exoplanetary systems, so we can contextualize our existence,” Balmer said. “We want to take pictures of other solar systems and see how they’re similar or different when compared to ours. From there, we can try to get a sense of how weird our solar system really is—or how normal.”

Image C: Young Gas Giant HR 8799 e (NIRCam Spectrum)

Of the nearly 6,000 exoplanets discovered, few have been directly imaged, as even giant planets are many thousands of times fainter than their stars. The images of HR 8799 and 51 Eridani were made possible by Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) coronagraph, which blocks light from bright stars to reveal otherwise hidden worlds.

This technology allowed the team to look for infrared light emitted by the planets in wavelengths that are absorbed by specific gases. The team found that the four HR 8799 planets contain more heavy elements than previously thought.

The team is paving the way for more detailed observations to determine whether objects they see orbiting other stars are truly giant planets or objects such as brown dwarfs, which form like stars but don’t accumulate enough mass to ignite nuclear fusion.

“We have other lines of evidence that hint at these four HR 8799 planets forming using this bottom-up approach” said Laurent Pueyo, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, who co-led the work. “How common is this for planets we can directly image? We don't know yet, but we're proposing more Webb observations to answer that question.”

“We knew Webb could measure colors of the outer planets in directly imaged systems,” added Rémi Soummer, director of STScI’s Russell B. Makidon Optics Lab and former lead for Webb coronagraph operations. “We have been waiting for 10 years to confirm that our finely tuned operations of the telescope would also allow us to access the inner planets. Now the results are in and we can do interesting science with it.”

The NIRCam observations of HR 8799 and 51 Eridani were conducted as part of Guaranteed Time Observations programs 1194 and 1412 respectively.

The James Webb Space Telescope is the world’s premier space science observatory. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.

Quelle: NASA