.

Giant asteroid lets off steam

Twin jets on asteroid Ceres, which has a surface area roughly the same as India, release 21 tonnes of water vapour every hour

.

Astronomers have spotted jets of steam coming from opposite sides of the largest asteroid in the solar system. The twin plumes of water vapour erupting from the space rock were noticed during a series of observations with the Herschel Space Telescope between October 2012 and March last year.

Researchers said the steam was produced either by the warmth of the sun vaporising ice beneath the surface, or a form of volcanic activity that is forcing water out of the asteroid's warm interior.

The scientists' calculations show that Ceres, technically a dwarf planet, releases around 21 tonnes of water vapour every hour from two dark patches on the surface. The amount is small for a ball of rock that measures 950km across and has roughly the same surface area as India.

"Asteroids have been suggested, along with comets, as a possible source of the water on Earth," said Michael Küppers, a planetary scientist at the European Space Astronomy Centre in Villanueva de la Cañada in Spain. "Our detection of water on Ceres makes it more plausible that Earth's water could have come from impacts from these bodies."

The Italian monk Giuseppe Piazzi discovered Ceres by accident on New Year's Day in 1801 while he was cataloguing stars in the constellation of Taurus. Piazzi named the rock – the first object discovered in the asteroid belt – after the Roman goddess of corn and harvests.

For the latest observations, reported in Nature, Küppers and his colleagues peered at Ceres through the European Space Agency's Herschel infra-red space telescope. They watched the comet for 2.5 hours on each of two days in October 2011, and for 10 hours in March 2013.

The telescope measured heat coming from the asteroid's surface and found that it lessened when the body was obscured by eruptions of water vapour. On the third day of observations, the astronomers took measurements as the asteroid completed a full revolution. From this, they concluded that water vapour was coming from two dark patches of ground on the asteroid's surface.

The asteroid was 2.7 AU (2.7 times the mean distance between the sun and Earth) from the sun when the astronomers made the observations. It was spinning about an axis perpendicular to the line of sight from the telescope, and made one full revolution every nine hours.

To work out how much water the asteroid was releasing, the scientists looked at how much infra-red radiation from the rock was absorbed by the vapour plumes. They calculated that the asteroid lost at least one hundred million billion billion molecules of water a second. Or 6kg.

Küppers said that most of the water vapour released by the asteroid was lost in space, with perhaps 20% falling back on to the surface of the rock. "I would not expect much of an atmosphere to form around Ceres," he said.

The dark patches of ground on Ceres might be craters that reach down to an icy layer that is not exposed on the rest of the asteroid. Or they may simply be made from darker material that absorbs more heat from the sun, causing surface ice to vaporise more readily.

"It's quite fascinating what's happening on Ceres," said Fred Taylor, Halley professor of physics at Oxford University. "Either water is escaping from inside, which can happen if you have heat in the interior, or it is coming from icy deposits on or near the surface."

"It's a tribute to the observers that they can see these tiny amounts of water," Taylor added. "Ceres is a major member of the solar system and learning about it is intriguing. You never go wrong with new knowledge."

The direct detection of water on Ceres adds weight to an idea of how objects have moved around in the solar system. The asteroid belt where Ceres orbits marks an effective "snow line" in the solar system. Objects that formed inside the snowline tend to be rocky and dry, while those that formed outside are icy. The discovery of water on Ceres suggests that some icy bodies that form beyond the snow line might gradually make their way into the asteroid belt.

Writing in an accompanying article in the journal, Humberto Campins and Christine Comfort at the University of Central Florida say that the movement of giant planets in the early solar system might have disturbed the orbits of asteroids and comets, which then crashed into the Earth and moon.

"These small bodies delivered organic molecules and water to Earth. Hence, early impacts by asteroids and comets might have played a considerable part in the origin and evolution of life on our planet."

Quelle: theguardian

.

ESA’s Herschel space observatory has discovered water vapour around Ceres

.

ESA’s Herschel space observatory has discovered water vapour around Ceres, the first unambiguous detection of water vapour around an object in the asteroid belt.

With a diameter of 950 km, Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt, which lies between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. But unlike most asteroids, Ceres is almost spherical and belongs to the category of ‘dwarf planets’, which also includes Pluto.

It is thought that Ceres is layered, perhaps with a rocky core and an icy outer mantle. This is important, because the water-ice content of the asteroid belt has significant implications for our understanding of the evolution of the Solar System.

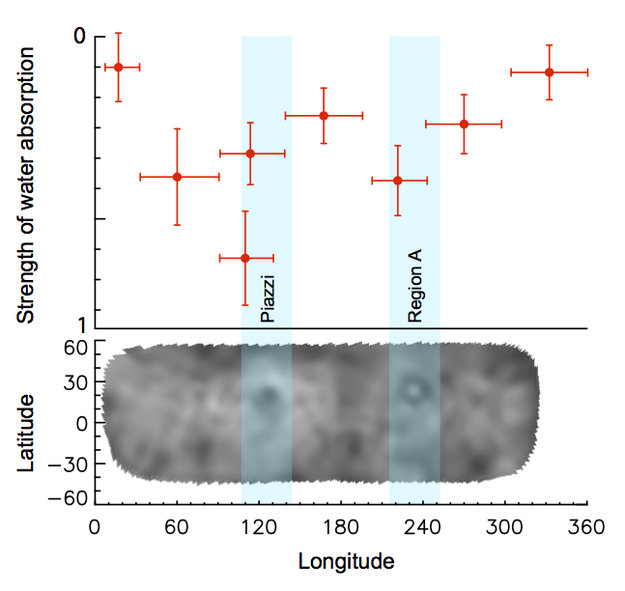

Variability in intensity of the water absorption signal detected at Ceres by ESA’s Herschel space observatory on 6 March 2013. The most intense readings correspond to two dark regions on the surface known as Piazzi and Region A, identified in the ground-based image of Ceres by the Keck II Observatory. The two data points at 110º longitude were taken in a time interval of about 9 hours – equal to the Ceres rotation period – showing that variability in the water vapour production is possible even on short periods.

When the Solar System formed 4.6 billion years ago, it was too hot in its central regions for water to have condensed at the locations of the innermost planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. Instead, it is thought that water was delivered to these planets later during a prolonged period of intense asteroid and comet impacts around 3.9 billion years ago.

While comets are well known to contain water ice, what about asteroids? Water in the asteroid belt has been hinted at through the observation of comet-like activity around some asteroids – the so-called Main Belt Comet family – but no definitive detection of water vapour has ever been made.

Now, using the HIFI instrument on Herschel to study Ceres, scientists have collected data that point to water vapour being emitted from the icy world’s surface.

“This is the first time that water has been detected in the asteroid belt, and provides proof that Ceres has an icy surface and an atmosphere,” says Michael Küppers of ESA’s European Space Astronomy Centre in Spain, lead author of the paper published in Nature.

Although Herschel was not able to make a resolved image of Ceres, the astronomers were able to derive the distribution of water sources on the surface by observing variations in the water signal during the dwarf planet’s 9-hour rotation period. Almost all of the water vapour was seen to be coming from just two spots on the surface.

“We estimate that approximately 6 kg of water vapour is being produced per second, requiring only a tiny fraction of Ceres to be covered by water ice, which links nicely to the two localised surface features we have observed,” says Laurence O’Rourke, Principal Investigator for the Herschel asteroid and comet observation programme called MACH-11, and second author on the Nature paper.

The most straightforward explanation of the water vapour production is through sublimation, whereby ice is warmed and transforms directly into gas, dragging the surface dust with it, and thus exposing fresh ice underneath to sustain the process. Comets work in this fashion.

The two emitting regions are about 5% darker than the average on Ceres. Able to absorb more sunlight, they are then likely the warmest regions, resulting in a more efficient sublimation of small reservoirs of water ice.

An alternative possibility is that geysers or icy volcanoes – cryovolcanism – play a role in the dwarf planet’s activity.

Much more detailed information on Ceres is expected soon, as NASA’s Dawn mission is currently en route there for an arrival in early 2015. It will provide close-up mapping of the surface and monitor how the water activity is generated and varies with time.

“Herschel’s discovery of water vapour outgassing from Ceres gives us new information on how water is distributed in the Solar System. Since Ceres constitutes about one fifth of the total mass of asteroid belt, this finding is important not only for the study of small Solar System bodies in general, but also for learning more about the origin of water on Earth,” says Göran Pilbratt, ESA’s Herschel Project Scientist.

Quelle: ESA

.

5338 Views