26.05.2024

Before its computer crashed, venerable NASA probe may have entered mysterious new region beyond the Solar System

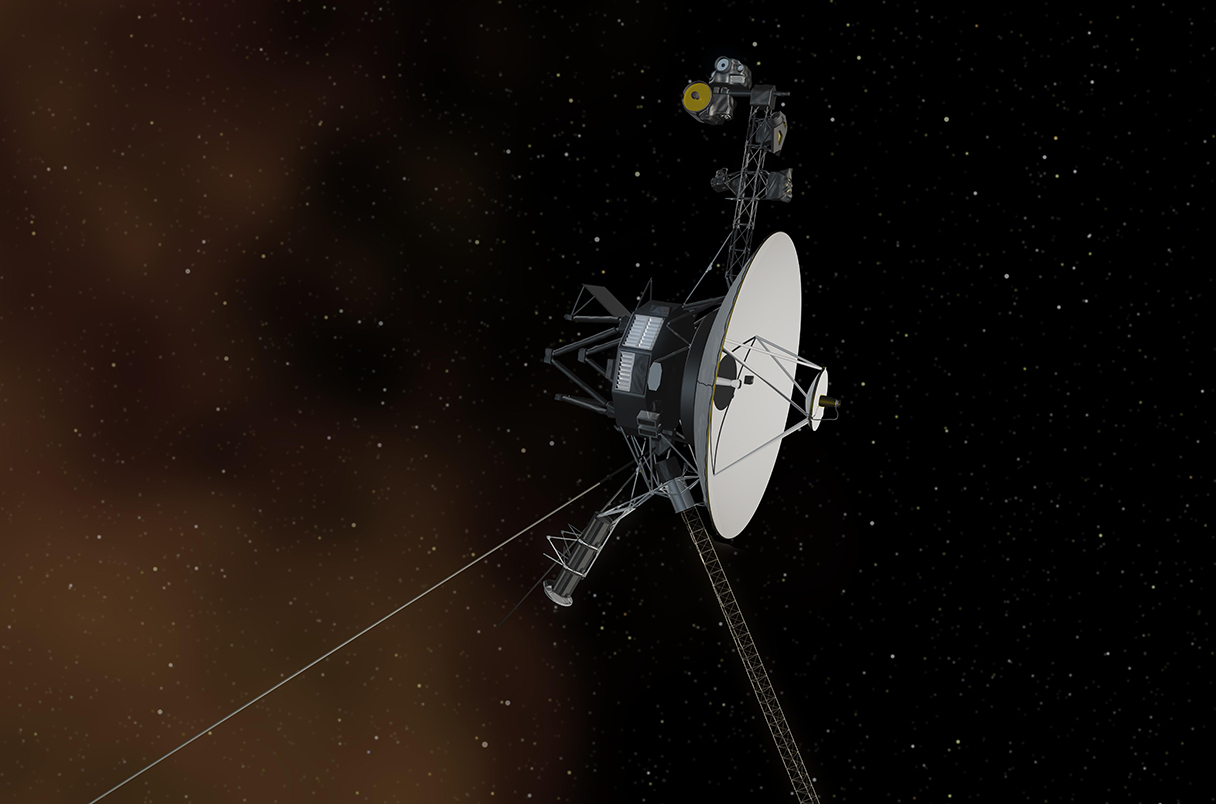

Voyager 1, the first earthly object to exit the Solar System, may be traversing a plasma cloud from another star.NASA/JPL-CALTECH

It was the ultimate remote IT service, spanning 24 billion kilometers of space to fix an antiquated, hobbled computer built in the 1970s. Voyager 1, one of the celebrated twin spacecraft that was the first to reach interstellar space, has finally resumed beaming science data back to Earth after a 6-month communications blackout, NASA announced this week. After a corrupted chip rendered Voyager 1’s transmissions unintelligible in November 2023, engineers nursed the spacecraft back to health. It began transmitting engineering data and then, on 17 May, science communications for two of its four remaining instruments.

“It was a nail biter,” says Jamie Rankin, an astrophysicist at Princeton University and Voyager’s deputy project scientist. Even after securing engineering data “it wasn’t clear whether or not we’d get science data back,” she says, adding that her team is both “excited and relieved.” NASA will attempt to resuscitate Voyager 1’s other two instruments in the coming weeks.

Voyagers 1 and 2 have faced other close calls during their 47-year journey through the outer Solar System and beyond, but Voyager 1’s communications crisis was unprecedented, says Alan Cummings, a physicist at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and a 51-year Voyager mission veteran. “This is the longest time we’ve been without data.”

Prior to the interruption, Voyager 1 had been traversing a mysterious new region of interstellar space—perhaps an enormous swell of pressure or a cloud of ancient plasma—and scientists are eager to resume the investigation.

The Voyagers launched in 1977 and sent back the first detailed images beyond Mars, capturing Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, the startling sight of volcanoes on the jovian moon Io, and the cerulean storms in Neptune’s atmosphere. Their mission complete, the probes continued toward the edge of the heliosphere—a bubble of plasma, inflated by the Sun, that surrounds the Solar System. Voyager 1 exited the heliosphere in 2012, the first earthly object to reach interstellar space. Voyager 2 followed in 2018.

With only 6 years of power remaining in their electric generators, which run off the heat from decaying plutonium, time is running short for the spacecraft. Mission managers have shut off six of Voyager 1’s 10 original instruments. Now that the spacecraft is outside the Sun’s protective bubble, its electronics are also vulnerable to strikes from galactic cosmic rays, charged particles accelerated to ultrahigh energies by supernovae and other cosmic engines.

That’s what NASA thinks might have happened last November, when Voyager 1 suddenly started to transmit a string of nonsensical binary code. An emergency team of engineers tried to pinpoint the issue, sending a few cautious commands at a time and waiting 45 hours for a reply from the probe, nearly a light-day away. To understand the system, they had to sift through half a century of documentation written by engineers who had mostly retired or passed away.

The team finally traced the problem to one dead memory chip, which stored code necessary for communications. The engineers redistributed the chip’s function across the computer’s remaining memory—first the commands necessary for engineering data and then, after careful consideration, those needed for science data. “It wasn’t clear at first that it would all fit,” Rankin says.

Before the breakdown, Voyager 1 had been investigating a mystery. In 2020 Voyager 1’s magnetometer registered an abrupt jump in the intensity of the magnetic fields embedded in the tenuous interstellar plasma while its plasma detector measured a rise in plasma density. Similar anomalies had been seen before, but the observations returned to baseline levels after a period of months. Researchers believe those transient jumps were generated when surges of plasma streaming outward from the Sun smashed against the boundary of the heliosphere, creating swells that reverberate through interstellar space, compressing interstellar plasmas and intensifying their magnetic fields. “The source is like a piston,” says Adam Szabo, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and principal investigator for the magnetometer.

The anomalies that began in 2020, however, did not abate, leading some mission scientists to question whether they originated with the Sun at all. Szabo thinks they could indicate that Voyager 1 has entered a small cloud of ancient interstellar plasma carrying the higher magnetic field of whatever star or star-forming region spat it out. Now, scientists are eager to see whether the two instruments—the ones now returning data—are still recording heightened field intensities and plasma densities after 6 months of silence. That could suggest Voyager 1 is still cruising through the cloud, Szabo says, and “truly make it a huge area.”

Szabo’s theory is just one of several that could explain the observations. Some scientists believe the new region is still just a pressure wave of solar origin, albeit one of unprecedented size. Others think these observations help show that Voyager 1 still hasn’t completely left the heliosphere.

Settling the matter won’t be easy. Stella Ocker, a postdoctoral fellow at Caltech and the Carnegie Observatories, says astronomers are good at observing things far off or inside our solar bubble, but struggle to see what’s in between. “It is surprisingly difficult to observe the interstellar medium that is just outside of our heliosphere.” The Voyager spacecraft are sort of “on the border of astro- and space-physics,” adds Chika Onubogu, a Ph.D. astronomy student at Boston University and a member of the NASA-funded SHIELD collaboration, which studies the heliosphere.

Even so, Voyager scientists say the ambiguous data are precious. It will be decades before a new interstellar science mission provides another “opportunity to initiate such fundamentally important and novel lines of research,” says Kostas Dialynas, an astrophysicist at the Academy of Athens and a co-investigator on one of Voyager 1’s energetic particle instruments.

For now, scientists are celebrating Voyager 1’s reawakening. The “Voyagers are traveling in completely uncharted territories,” Dialynas says. “We have no idea what lies ahead.”

Quelle: AAAS