17.04.2024

Venus is leaking carbon and oxygen, a fleeting visit by BepiColombo reveals

"These are heavy ions that are usually slow moving, so we are still trying to understand the mechanisms that are at play."

An abundance of gases, including carbon and oxygen, are being stripped away from Venus' atmosphere, according to flyby data from Europe's BepiColombo space probe. This data was obtained as the Mercury-bound spacecraft flew past Venus, and could shed new light on the leaky atmosphere of our planetary neighbor. Down the line, the findings could help scientists catalog the makeup of Venus' fragile magnetic environment as well.

Unlike Earth, a planet with an intrinsic magnetic field that protects its atmosphere from escaping into the depths of space, Venus does not possess its own, stable magnetic field. That is because its cooler interior cannot slosh around molten material, a swirling necessary to create and sustain a magnetic field. Rather, sunlight battering on the amber-hued orb charges up its atmospheric atoms, which then create electric currents that produce an unstable, sunlight-dependent magnetosphere.

In August 2021, BepiColombo flew through this weak, comet-shaped magnetosphere for 90 minutes to slow down and adjust its course while heading toward its ultimate target, Mercury. Scientists analyzing data from the spacecraft's fleeting visit, however, found some valuable Venusian information. Charged particles, or ions, appeared to be escaping the planet due to sunlight accelerating molecules in the atmosphere to extremely high speeds. Those speeds were high enough, in fact, that the ions even escaped the planet's gravityand flowed out into space.

"These are heavy ions that are usually slow moving, so we are still trying to understand the mechanisms that are at play," Lina Hadid, a researcher at the Plasma Physics Laboratory in France who led the new analysis, said in a statement.

Venus' thick, hellish atmosphere is dominated by carbon dioxide, but also holds fewer amounts of nitrogen and other trace gases. Scientists previously knew tiny amounts of oxygen lofted in Venus' night-side and, last November, a different team of researchers detected the molecule on the planet's day-side too. The latter team further concluded that Venus' oxygen concentration drops in tandem with decreasing solar radiation.

Investigating the loss of these molecules and their escape mechanisms "is crucial to understand how the planet's atmosphere has evolved and how it has lost all its water," study co-author Dominique Delcourt, who is also a researcher at the Plasma Physics Laboratory, said in the same statement.

BepiColombo is nearing the end of its seven-year journey and is expected to reach Mercury in late 2025. Meanwhile, a fleet of robotic visitors are scheduled to visit Venus in the coming decade. Europe's Envision spacecraft aims to launch in 2031 while NASA's DAVINCI, originally slated for a 2029 launch, was delayed to 2031.

The resurrected VERITAS mission is now scheduled to launch no earlier than 2031 as well, although team members are still advocating for an earlier launch in November 2029.

This research is described in a paper published Friday (April 12) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 16.05.2024

.

Glitch on BepiColombo: work ongoing to restore spacecraft to full thrust

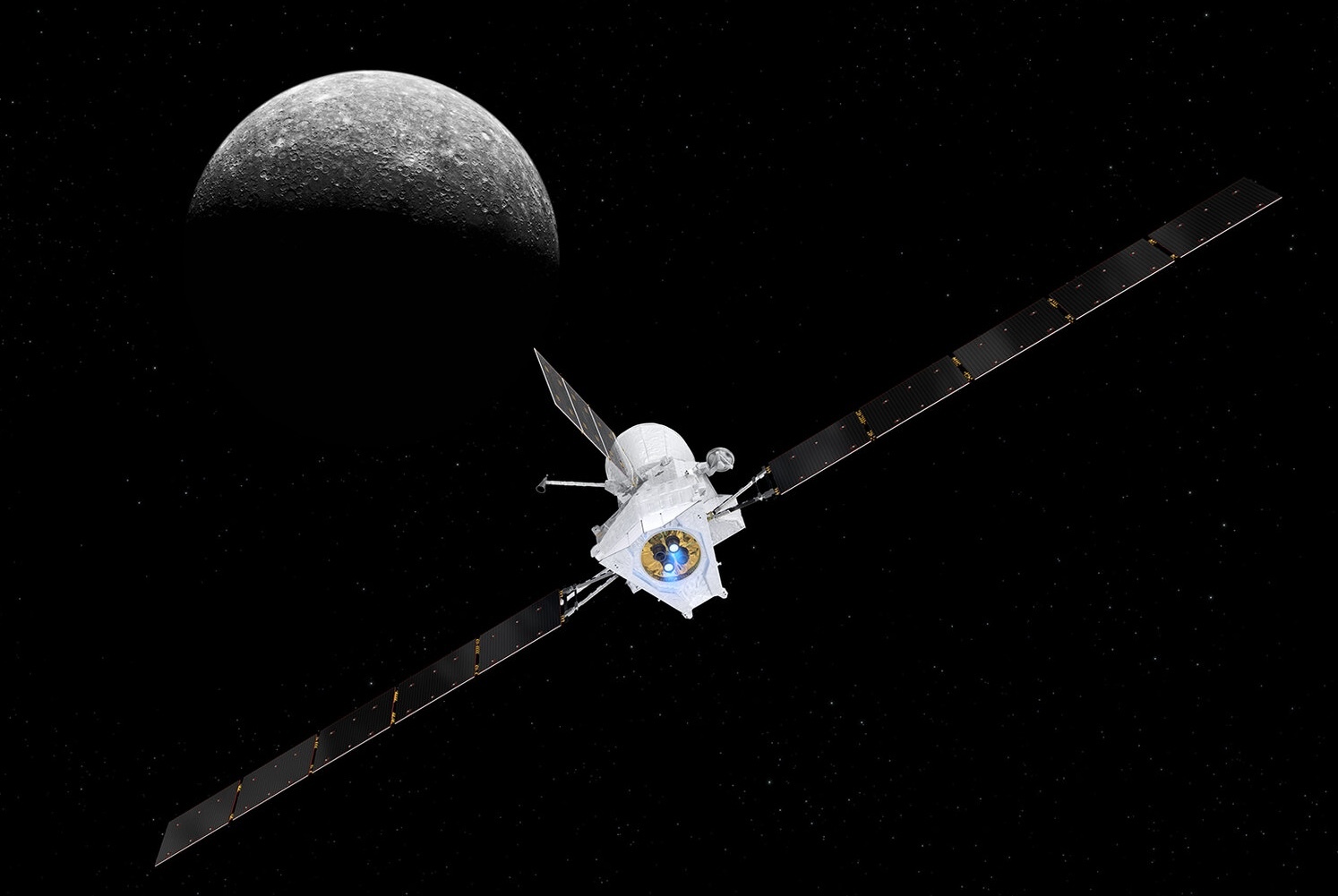

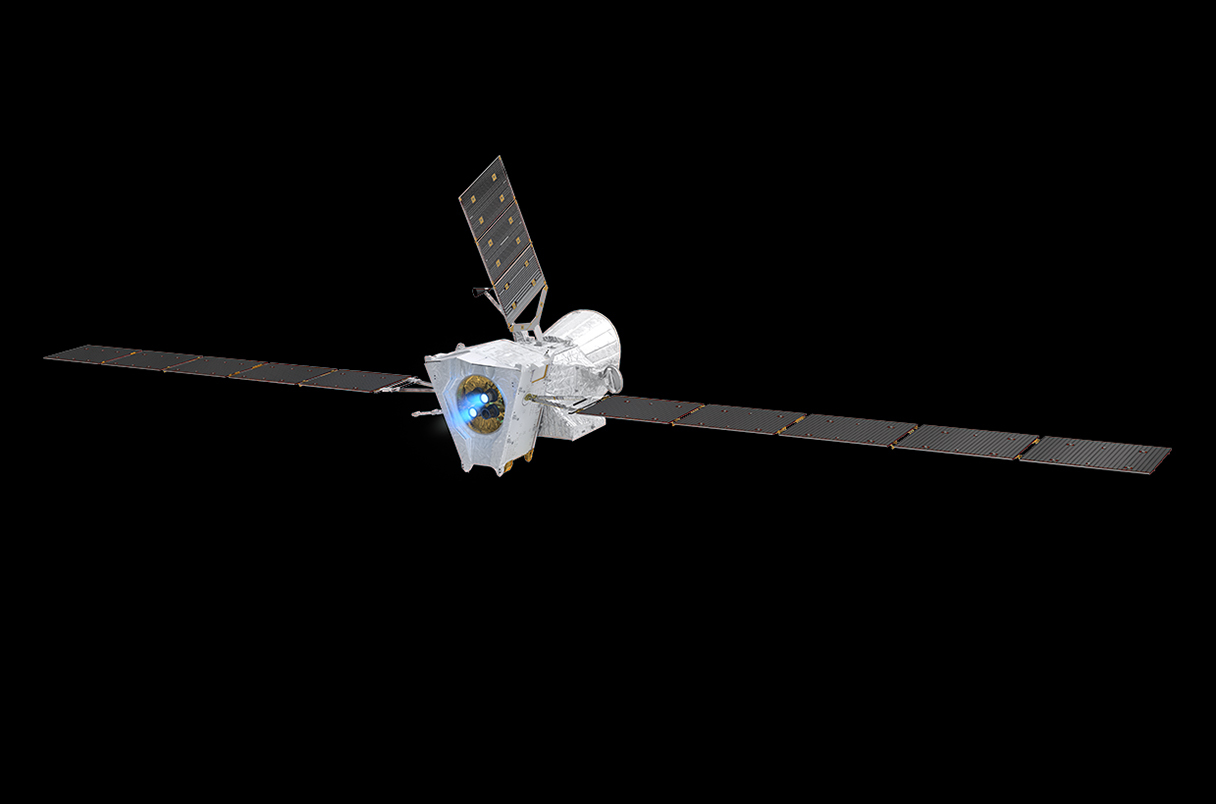

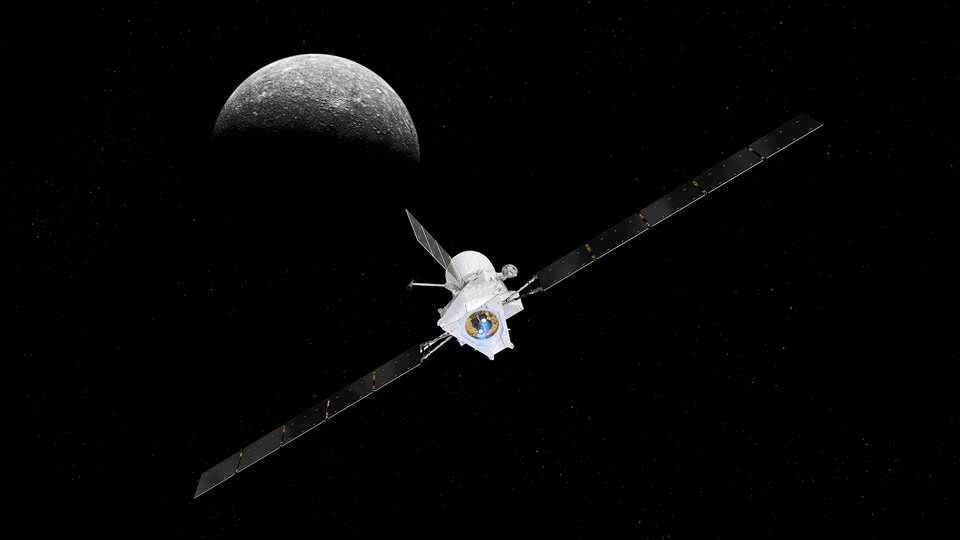

BepiColombo, the joint ESA/JAXA mission to Mercury, has experienced an issue that is preventing the spacecraft’s thrusters from operating at full power.

BepiColombo is a three-part spacecraft consisting of two scientific probes and the Mercury Transfer Module, which are designed to separate from one another as part of the mission’s Mercury orbit insertion operations.

The solar arrays and electric propulsion system on the Mercury Transfer Module are used to generate thrust during the spacecraft’s complex journey from Earth to Mercury.

However, on 26 April, as BepiColombo was scheduled to begin its next manoeuvre, the Transfer Module failed to deliver enough electrical power to the spacecraft’s thrusters.

A combined team from ESA and the mission’s industrial partners set to work the moment the issue was identified. By 7 May, they had restored BepiColombo’s thrust to approximately 90% of its previous level. However, the Transfer Module’s available power is still lower than it should be, and so full thrust cannot yet be restored.

The team’s current priorities are to maintain stable spacecraft propulsion at the current power level and to estimate how this will affect upcoming manoeuvres. Work continues in parallel to identify the root cause of the issue and to maximise the power available to the thrusters.

The BepiColombo Flight Control Team working at ESA’s ESOC mission control centre in Darmstadt, Germany, has arranged additional ground station passes in order to closely monitor the spacecraft and react rapidly if needed.

If the current power level is maintained, BepiColombo should arrive at Mercury in time for its fourth gravity assist at the planet in September this year. Final orbit insertion at Mercury is scheduled for December 2025 and the start of routine science operations for Spring 2026.

Updates will be shared as new information becomes available.

BepiColombo is a joint mission between ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to Mercury, the least explored planet of the inner Solar System.

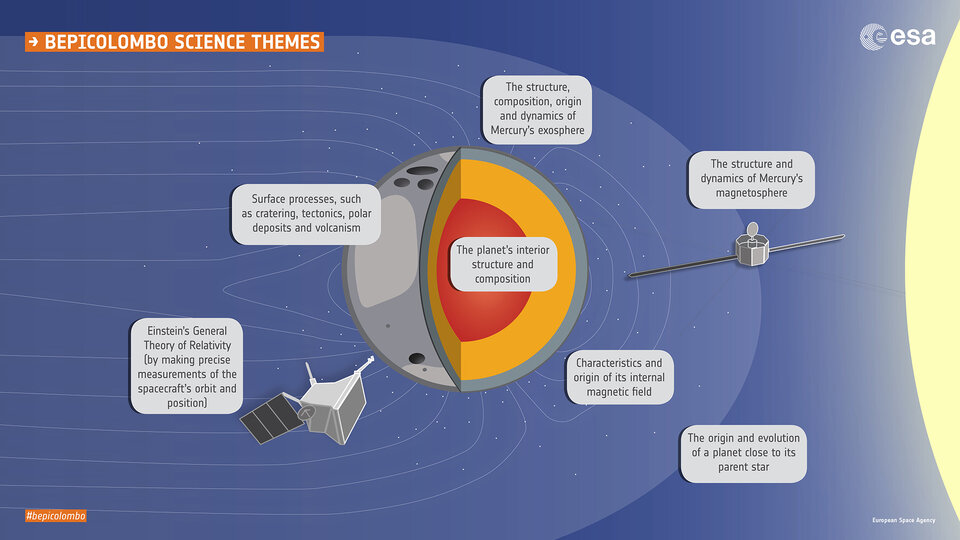

The mission features two scientific spacecraft, which will be inserted into different orbits around Mercury: ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter. Both continue to perform excellently. Packed with scientific instruments, they are designed to study Mercury’s composition, atmosphere, magnetosphere and history, and to address long-standing questions on the formation and evolution of our Solar System.

Quelle: ESA

----

Update: 6.06.2024

.

BepiColombo probe hits a glitch on its way to Mercury

Managers say cut in thruster power does not threaten European-Japanese mission, but schedule impact is unclear

The long voyage of the BepiColombo mission to Mercury may get longer because of a drop in power supplied to its ion propulsion system. On 26 April, the European-Japanese mission was preparing for a braking maneuver during a Mercury flyby when managers discovered the power drop. Operators restored 90% of the thrust by 7 May but the cause of the problem remains unclear. The ion drive, which uses electricity from the craft’s solar panels to accelerate ions and generate a steady, weak thrust, still isn’t back to full strength.

Despite the setback, which the European Space Agency (ESA) called a “glitch” in a 15 May statement, managers remain optimistic about the craft safely reaching Mercury. “We will still be able to insert BepiColombo into a Mercury orbit,” says Johannes Benkhoff, the mission scientist for ESA. The scheduled arrival, in December 2025, could slip, however.

Launched in October 2018 and jointly developed by ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the €1.65 billion ($1.8 billion) BepiColombo is ferrying two scientific probes to be released into separate Mercury orbits. The Mercury Planetary Orbiter, built by ESA, carries 11 instruments and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetosphere Orbiter carries five. Together they will probe the planet’s huge iron core, the volatile elements in its crust, and its skewed magnetic field in search of clues to its formation history.

To get there, the spacecraft has to follow a circuitous flight path that so far has included a swing around Earth, two Venus flybys, and three passes by Mercury. The original schedule calls for three more Mercury flybys in September, December, and January 2025 that would slow the spacecraft enough to put the two scientific probes in position for orbit insertion around the planet in December 2025. This would set the stage for 1 year of science observations, commencing in spring 2026.

The spacecraft’s ion propulsion system brakes and accelerates the spacecraft for these complex maneuvers. The undefined “glitch” led to a drop in the electrical power that strips electrons from neutral xenon gas atoms and accelerates the resulting positive ions to produce thrust far more efficiently than chemical rockets.

If the current 90% thrust level can be maintained, BepiColombo should arrive at Mercury on time for the September flyby. “We expect that if this (first) swing-by is met, the other two will be met as well,” Elsa Montagnon, BepiColombo spacecraft operations manager, said in an email to ScienceInsider. Benkhoff explains that operating the thrusters for longer can compensate for the lower power. “Since we never planned to operate our thrusters continuously, we have some margin,” he says. Even if one of the flybys is missed, the craft’s orbit around the Sun will repeatedly bring it close to Mercury.

The overall impact on the schedule is unclear, says Go Murakami, a planetary scientist at JAXA’s Institute of Space and Astronautical Science. “The team is still investigating the effect of this [power] issue on the upcoming schedule,” he says. He adds that the ideal solution would be to “find the root cause of the power issue.”

Quelle: AAAS

----

Update: 3.09.2024

.

Fourth Mercury flyby begins BepiColombo’s new trajectory

Teams from across ESA and industry have worked continuously over the past four months to overcome a glitch that prevented BepiColombo’s thrusters from operating at full power. The ESA/JAXA mission is still on track, with a new trajectory that will take it just 165 km from Mercury’s surface on Wednesday.

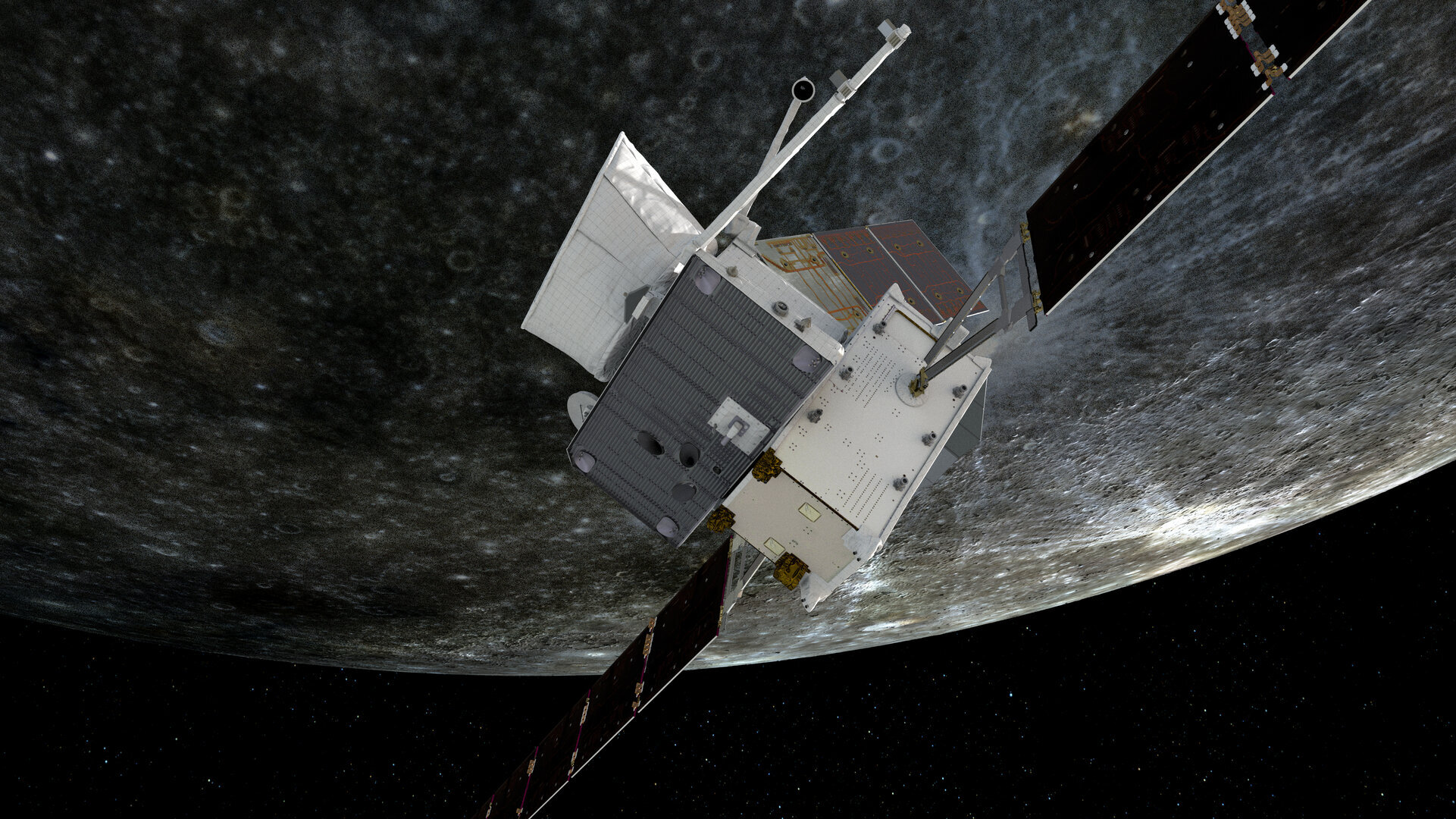

Taking BepiColombo closer to Mercury than it’s ever been before, this flyby will reduce the spacecraft’s speed and change its direction. It also gives us the opportunity to snap images and fine-tune science instrument operations at Mercury before the main mission begins. Closest approach is scheduled for 23:48 CEST (21:48 UTC) on 4 September.

BepiColombo launched into space in October 2018 and is making use of nine planetary flybys: one at Earth, two at Venus, and six at Mercury, to help steer itself into orbit around Mercury. Once in orbit, the main science phase of the mission can begin.

The upcoming flyby will be the fourth at Mercury. Whilst it was always in the schedule, BepiColombo will get around 35 km closer to Mercury than originally planned, due to a new route devised by ESA’s flight dynamics team.

Why is it so hard to visit Mercury?

Mercury is the least explored rocky planet of the Solar System, mainly because getting there is incredibly challenging. As BepiColombo gets closer to the Sun, the powerful gravitational pull of our star accelerates the spacecraft towards it. What’s more, the spacecraft launched from Earth with a lot of energy, travelling far too quickly to be captured into orbit around little Mercury.

Overcoming both of these hurdles would be enormously difficult using onboard thrusters alone. So BepiColombo also makes use of gravity assist flybys to help it lose energy and slow down enough to eventually be captured into orbit around Mercury.

BepiColombo’s journey to Mercury becomes even more epic

BepiColombo is unique in that it comprises two science orbiters that will circle Mercury – ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter. The two are carried together to the mysterious planet by the Mercury Transfer Module (MTM). In April 2024, BepiColombo started experiencing an issue that prevented MTM’s electric thrusters from operating at full power.

Engineers identified unexpected electric currents between MTM’s solar array and the unit responsible for extracting power and distributing it to the rest of the spacecraft. Onboard data imply that this is resulting in less power available for electric propulsion.

ESA’s BepiColombo Mission Manager, Santa Martinez explains: “Following months of investigations, we have concluded that MTM’s electric thrusters will remain operating below the minimum thrust required for an insertion into orbit around Mercury in December 2025.”

A workaround to MTM’s reduced thrust has been cleverly devised by ESA’s Flight Dynamics team. They conceived a new trajectory that maintains the baseline scientific mission at Mercury but allows the spacecraft to use lower thrust during the cruise phase of the mission. With this new trajectory, BepiColombo is now expected to arrive at Mercury in November 2026.

Each of BepiColombo’s fourth, fifth (December 2024) and sixth (January 2025) Mercury flybys are going ahead as planned. All three will change the spacecraft’s speed and direction, bringing it more in tune with the orbit of Mercury around the Sun.

MTM will fire its thrusters in September to October 2024 to put BepiColombo onto its new trajectory. The fourth flyby takes BepiColombo closer than planned to Mercury, helping reduce the propulsion needed to reach the fifth flyby. The sixth flyby will then be used to branch onto the new trajectory.

Science at Mercury: a teaser of what’s to come

Beyond the later arrival date, the rest of the BepiColombo mission is expected to go ahead as planned, and the scientific objectives will not be affected. ESA expects the same science to come out of the mission, with data gathered by a suite of 16 instruments across the two orbiters.

Ten of these instruments can be operated during this week’s flyby, giving us another taste of what scientific discoveries we can expect from the main mission. Magnetic, plasma and particle monitoring instruments will sample the environment before, during and after closest approach. The other instruments cannot be operated because their fields of view are blocked by the carrier spacecraft.

“It’s so exciting that BepiColombo can boost our understanding and knowledge of Mercury during these brief flybys, despite being in ‘stacked’ cruise configuration,” says Johannes Benkhoff, BepiColombo Project Scientist.

“We get to fly our world-class science laboratory through diverse and unexplored parts of Mercury’s environment that we won’t have access to once in orbit, while also getting a head start on preparations to make sure we will transition into the main science mission as quickly and smoothly as possible.”

Testing out the instruments during flybys is valuable for the science teams to check that their instruments are functioning correctly ahead of the main mission.

The simulation below shows the path that BepiColombo will take through Mercury’s magnetic environment during the upcoming flyby. Various instruments will collect data on magnetic and electric field strength, as well as measuring the particles around Mercury, revealing totally new information about the planet’s magnetic environment. Click on the video to find out more.

BepiColombo’s best view yet of Mercury

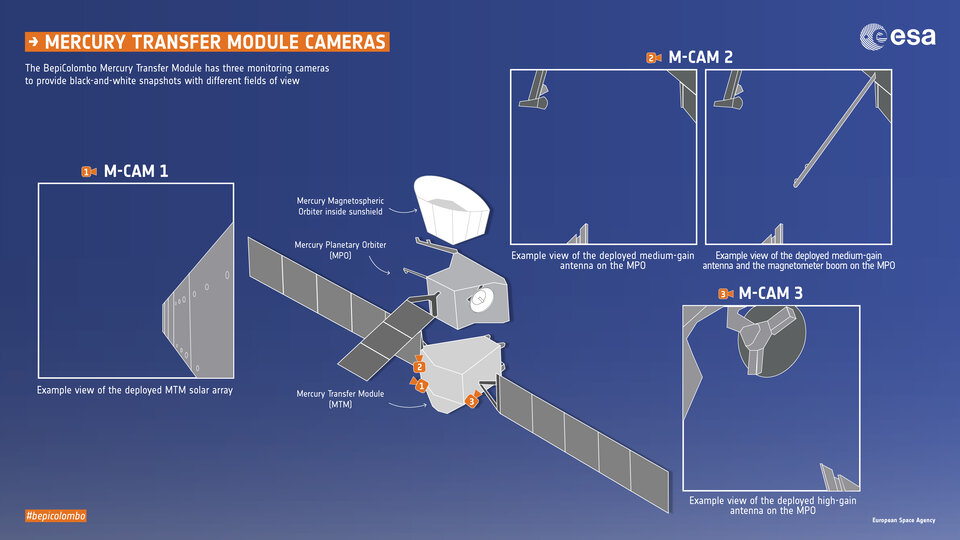

BepiColombo’s main science camera is shielded until the ESA and JAXA orbiters separate, but during flybys images are taken by the three monitoring cameras (M-CAMs) on the Mercury Transfer Module.

The cameras provide black-and-white 1024x1024 pixel snapshots. Their images of Mercury are a bonus: the cameras were actually designed to monitor the spacecraft's solar array, antenna and magnetometer boom, especially in the challenging period after launch.

As BepiColombo passes Mercury, well-lit images will begin to be taken by M-CAM 2 and M-CAM 3 two minutes after closest approach, when BepiColombo is around 200 km from Mercury’s surface. M-CAM 1 will have a beautiful view of Mercury receding into the distance.

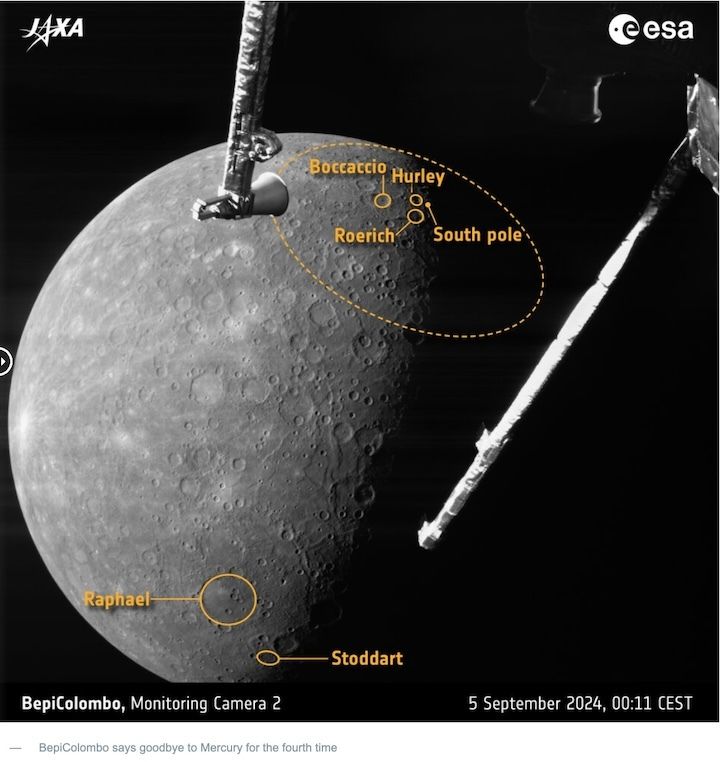

This flyby will also be the first to take BepiColombo over Mercury’s poles, helping to adjust the spacecraft’s trajectory to match that of Mercury, which is inclined compared to Earth’s orbit. We expect to be able to share BepiColombo's first stunning views of the planet’s south pole.

The first images will be downlinked a few hours after closest approach and are expected to be released on 5 September. The closest images are expected to reveal large craters, wrinkle ridges, lava plains and much more, helping scientists unlock the secrets of Mercury’s 4.6-billion-year history and its place in the evolution of the Solar System.

All images are scheduled to be released publicly in the Planetary Science Archive later in September. The first science results from data collected during the flyby will be released on 13 September.

Quelle: ESA

----

Update: 10.09.2024

.

BepiColombo's best images yet highlight fourth Mercury flyby

The ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission has successfully completed its fourth of six gravity assist flybys at Mercury, capturing images of two special impact craters as it uses the little planet’s gravity to steer itself on course to enter orbit around Mercury in November 2026.

The closest approach took place at 23:48 CEST (21:48 UTC) on 4 September 2024, with BepiColombo coming down to around 165 km above the planet’s surface. For the first time, the spacecraft had a clear view of Mercury’s south pole.

“The main aim of the flyby was to reduce BepiColombo’s speed relative to the Sun, so that the spacecraft has an orbital period around the Sun of 88 days, very close to the orbital period of Mercury,” says Frank Budnik, BepiColombo Flight Dynamics Manager.

“In this regard it was a huge success, and we are right where we wanted to be at this moment. But it also gave us the chance to take photos and carry out science measurements, from locations and perspectives that we will never reach once we are in orbit.”

Images from BepiColombo’s three monitoring cameras have arrived back on Earth, providing a unique view of Mercury’s surface from three different angles. BepiColombo approached Mercury from the ‘nightside’ of the planet, with Mercury’s cratered surface becoming increasingly lit up by the Sun as the spacecraft flew by.

M-CAM 2 provided the best views of the planet during this flyby, capturing more and more of the planet as BepiColombo came round to the side of Mercury lit by the Sun. M-CAM 3 also chipped in a stunning image of a newly named impact crater.

M-CAMs 2 and 3 are now switched off, but M-CAM 1 will continue imaging Mercury until about midnight tonight (24 hours after closest approach), getting a beautiful view of the planet receding into the distance.

Mercury lays bare its Four Seasons

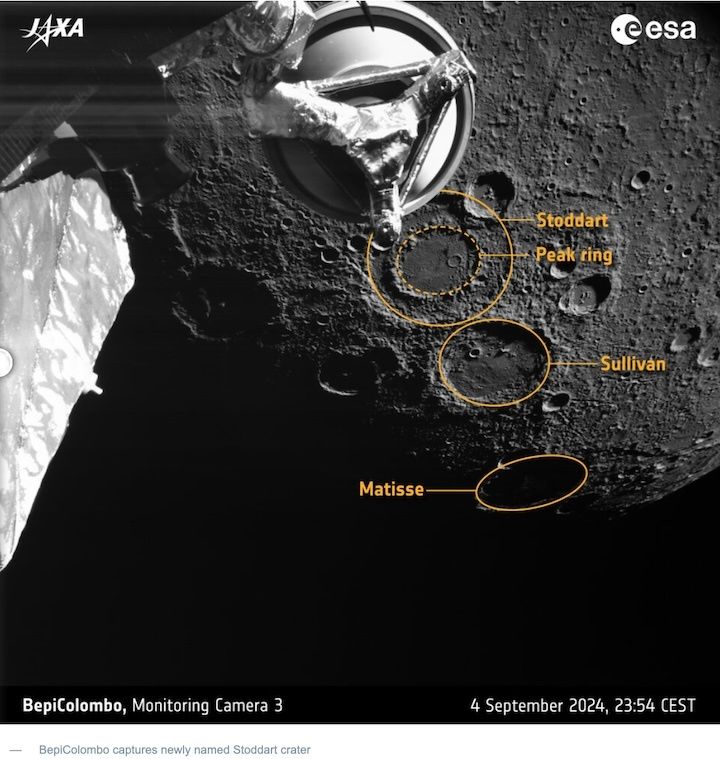

Four minutes after closest approach, a large ‘peak ring basin’ came into BepiColombo’s view. These mysterious craters – created by powerful asteroid or comet impacts and measuring about 130–330 km across – are called peak rings basins after the inner ring of peaks on an otherwise flattish floor.

This large crater is Vivaldi, after the famous Italian composer Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741). It measures 210 km across, and because BepiColombo saw it so close to the sunrise line, its landscape is beautifully emphasised by shadow. There is a visible gap in the ring of peaks, where more recent lava flows have entered and flooded the crater.

First sight of crater newly named after New Zealand artist

Just a couple of minutes later, another special peak ring basin came into view. This one measures 155 km across.

“When we were planning for this flyby, we saw that this crater would be visible and decided it would be worth naming due to its potential interest for BepiColombo scientists in the future,” explains David Rothery, Professor of Planetary Geosciences at the UK’s Open University and a member of the BepiColombo M-CAM imaging team.

Following a request from the M-CAM team, the ancient crater was recently assigned the name Stoddartby the International Astronomical Union’s Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature after Margaret Olrog Stoddart (1865–1934), an artist from New Zealand known for her flower paintings.

“Mercury’s peak ring basins are fascinating because many aspects of how they formed are currently still a mystery. The rings of peaks are presumed to have resulted from some kind of rebound process during the impact, but the depths from which they were uplifted are still unclear,” continues David.

Many of Mercury’s peak ring basins have been flooded by volcanic lava flows long after the original impact. This has happened inside both Vivaldi and Stoddart. Inside Stoddart, the trace of a 16-km-wide crater that must have formed on the original floor is clearly visible through a covering of more recent lava flows.

Peak ring basins are among the high-priority targets for study by BepiColombo once it gets into orbit around Mercury and is able to deploy its full suite of scientific instruments.

A taste of Mercury science

The snapshots seen during this flyby are among BepiColombo’s best so far – taken from the closest distance yet, with Mercury’s surface well-lit by the Sun. They reveal a surface with clear signs of 4.6 billion years of bombardment by asteroids and comets, hinting at the planet’s place in the wider Solar System evolution.

It’s worth remembering that these images are a bonus: the M-CAMs were not designed to photograph Mercury but the spacecraft itself, especially during the challenging period just after launch. They provide black-and-white 1024x1024 pixel snapshots. BepiColombo’s main science camera is shielded during the journey to Mercury, but it is expected to take much higher-resolution images after arrival in orbit.

In 2027, the main science phase of the mission will begin. The spacecraft’s suite of science instruments will reveal the invisible about the Solar System’s most mysterious planet, to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its host star.

But the work has already begun, with most of the instruments switched on during this flyby, measuring the magnetic, plasma and particle environment around the spacecraft, from locations that will not be accessible when BepiColombo is actually in orbit around Mercury.

BepiColombo comprises two science orbiters that will circle Mercury – ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter. The two are carried together to the mysterious planet by the Mercury Transfer Module. Even though the three parts are currently in ‘stacked’ cruise configuration, meaning many instruments cannot be fully operated, they can still get glimpses of science and enable instrument teams to check that their instruments are working well ahead of the main mission.

"BepiColombo is only the third space mission to visit Mercury, making it the least-explored planet in the inner Solar System, partly because it is so difficult to get to," says Jack Wright, ESA Research Fellow, Planetary Scientist, and M-CAM imaging team coordinator.

"It is a world of extremes and contradictions, so I dubbed it the ‘Problem Child of the Solar System’ in the past. The images and science data collected during the flybys offer a tantalising prelude to BepiColombo's orbital phase, where it will help to solve Mercury's outstanding mysteries."

What’s next?

This fourth Mercury flyby has lined BepiColombo up for a fifth and sixth flyby of the planet on 1 December 2024 and 8 January 2025. Each is bringing the spacecraft more in tune with the orbit of Mercury around the Sun.

The BepiColombo flight control team will remain extra busy until the end of the sixth flyby, after which they return to normal cruise operations for almost two years, until BepiColombo enters orbit around Mercury in November 2026.

Quelle: ESA