Astrobotic's Peregrine lunar lander will now attempt a landing near a region called the Gruithuisen Domes that is the target of a future CLPS mission. Credit: Astrobotic

WASHINGTON — NASA and Astrobotic have changed the landing site for the company’s first lunar lander mission shortly before its scheduled launch, moving the mission to a location of greater scientific interest.

NASA announced Feb. 2 the Astrobotic’s Peregrine mission, flying payloads for the agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program and other customers, will now attempt a landing near a region called the Gruithuisen Domes on the northeast edge of Oceanus Procellarum, or Ocean of Storms, on the western part of the moon’s near side.

Astrobotic had originally targeted a region called Lacus Mortis, a basaltic plain on the northeastern side of the near side of the moon, based on the projected performance of the lander and a desire for a relatively safe landing area. That was the landing location identified when NASA awarded one of the first CLPS task orders to Astrobotic for the mission in May 2019.

“However, as NASA’s Artemis activities mature, it became evident the agency could increase the scientific value of the NASA payloads if they were delivered to a different location,” the agency said in a statement announcing the landing site change. NASA is planning to send an instrument suite called Lunar-VISE to the Gruithuisen Domes on a future CLPS mission to study that region to understand why they appear to be rich in silica.

Sending Peregrine to a region near the Gruithuisen Domes, NASA stated, “will present complementary and meaningful data to Lunar-VISE without introducing additional risk to the lander.”

There had been signs that NASA was planning a change in Peregrine’s landing site. In a presentation to NASA’s Planetary Science Advisory Committee Dec. 6, Joel Kearns, NASA deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, showed a map of CLPS landing locations that showed Peregrine landing near Gruithuisen Domes.

The announcement did not provide an update on the anticipated launch date of Peregrine on the inaugural flight of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket. Astrobotic said Jan. 25 it had completed testing of the lander and was awaiting the “green light” from ULA to ship the spacecraft to Cape Canaveral for pre-launch processing. The rocket itself arrived at Cape Canaveral last month and ULA is preparing it for tests leading up to the launch.

Their “Peregrine” lander, filled with scientific instruments and other payloads from NASA and several other government agencies and non-government organizations and companies, will be part of the debut of the United Launch Alliance’s new Vulcan Centaur launcher. The earliest window, as announced on Twitter by Astrobotic, will be on May 4th, 2023.

The lunar lander company, formed in 2007 by Carnegie Mellon University professor Red Whittaker in a bid to win the X-PRIZE for a private landing on the moon, has been promising affordable and attainable access to the lunar surface for both governmental and non-governmental clients. They plan to leverage the swiftly-falling cost of sending material into orbit to build a business taking payloads to the Moon, and have received significant support from NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, including a US$79.5m contract in 2019 for the delivery of 14 payloads to the Moon.

The Peregrine lander itself is a small-class lander, which is preceding their medium-class Griffin lander that is still being prepared for a later mission on the SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket. According to the Peregrine payload users guide, It’s 2.5m x 1.9m, has different configurations for polar and mid-latitude landings, can deliver payloads into several lunar orbits and lunar landing sites, and has five main engines from Dynetics as well as attitude control thrusters from Frontier Aerospace developed as part of the NASA TALOS program. It even has a WLAN network for the rovers.

It will be landing at the “Gruithuisen Domes,” on the northeast edge of the Oceanus Procellaraum. It was originally going to be landing at Lacus Mortis, but Astrobotic changed the location at NASA’s request, as NASA will be sending a future CLPS mission to the Domes in the future that it believes will be complemented by Peregrine’s payloads.

Astrobotic will be relying on ULA’s Vulcan Centaur as their launcher, thanks to a deal that goes back to 2017. Yet while the rocket was originally supposed to launch in 2021, delays with both the rocket and the lander led to the mission getting repeatedly pushed back, making its new confirmed date even more notable, even if it is only the first window.

ULA is a joint venture between Lockheed Martin and Boeing. While these companies are critically important in the aerospace and defence sectors, issues with the rocket engines on their Atlas V rockets and delays on the debut of the Vulcan Centaur have caused them to fall behind SpaceX in the commercial and governmental launch space. This high-visibility Astrobotic lunar mission will be their big chance to regain their momentum in the face of the growth of not only SpaceX, but of other launcher companies like Rocket Lab and Firefly.

That said, the Vulcan Centaur itself is not completely untested. Replacing their “workhorse” Atlas V and Delta IV rockets, and built to meet the needs of the National Security Space Launch (NSSL) program, it includes a mix of newer and established parts, including some that date back to the mid-20th century. Its “Centaur V” upper stage is an evolution of the venerable “Centaur” upper stage that dates back to the 1960s, and includes upgraded versions of the RL10-C liquid hydrogen/oxygen rocket engine. Its 4 GEM-63XL solid rocket boosters are familiar technology as well.

Its lower stage, however, uses the all-new Blue Origin BE-4 engine, as the RD-180 engines that the Atlas V relied on were Russian-made, a situation which was made untenable after Russian annexed Crimea in 2014.

These issues appear to be sorted out, and the Vulcan Centaur’s twin BE-4 engines should be ready to go for the upcoming launch. In fact, the most recent delay in the Vulcan Centaur launch, from 2022 to 2023, was at the request of Astrobotic in order to finish the Peregrine.

The Vulcan Centaur will also be carrying two prototype satellites for Amazon’s Project Kuiper constellations.

As readers can see from this extensive manifest, a lot is riding on the success of the Vulcan Centaur and the Peregrine lander.

"Yes, it's Christmas Eve. But it will be one heck of a Christmas present."

Artist's illustration of Astrobotic's Peregrine lander on the surface of the moon. (Image credit: Astrobotic)

During the wee hours of Christmas Eve this year, before the gift wrapping begins and the aroma of gingerbread brightens the air, a spacecraft is set to launch to the moon.

It's called the Peregrine Lunar Lander, named for the fastest flying bird on Earth. If all goes to plan, the robotic avian will zoom through space and fly into the moon's gravitational tides, then meticulously lower its orbit until eventually touching down on a region of ancient lunar lava flows known as the Bay of Stickiness, or Sinus Viscositatis.

This mission will be one for the history books for several reasons, one of which is the fact it'll be the first to launch under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative, created as a way for the agency to bring payloads to the moon without having to construct all the spacecraft necessary to bring those payloads there. In this case, the company Astrobiotic is behind the Peregrine lander and NASA's paying to stash a few things onboard.

As for the rocket, there's another first to discuss. Peregrine will be lifting off on the first flight of United Launch Alliance's Vulcan Centaur rocket. The successor to the company's Atlas V and Delta IV vehicles, Vulcan Centaur is, among other things, built to carry quite a hefty amount of stuff to space.

And during a briefing on Nov. 29, representatives with Astrobiotic, United Launch Alliance and, of course, NASA, gathered to discuss what some of the Peregrine payloads are going to be as well as lay out how everything is expected to go down the day before Christmas.

What's heading to the moon?

There are five total NASA-sponsored payloads heading to the lunar surface during the mission, and the first is known as the "Peregrine ion trap mass spectrometer," or PITMS.

PITMS will be investigating the lunar exosphere, which is a thin gaseous envelope around the moon, by tapping into mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry simply refers to the technique scientists use to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions, which are charged particles like hydrogen atoms that hold a positive proton, but no negative electron to balance the proton out.

"The science results from PITMS will aim to improve our knowledge of the abundance and behavior of volatiles on the moon and how they respond to perturbations such as rocket exhaust," Ryan Watkins, program scientist at NASA's Exploration Science Strategy and Integration Office, said.

Peregrine will also be bringing a neutron spectrometer system, or NSS, Watkins explained, which will measure the amount of neutrons near the lunar surface as well as their associated energies. By deduction, NSS will help scientists figure out how much hydrogen is present in the environment as well as levels of soil hydration.

The lunar retroreflector array, or LRA, getting launched on Peregrine in December is a device that consists of eight "retroreflectors," which Watkins compares to small mirrors on a small aluminum support structure: "The LRA will enable precision laser ranging to help determine the distance from any orbiting or landing spacecraft to the LRA that will be on the lander. So LRA is a passive optical instrument, and it's going to function as a permanent location marker on the moon for decades to come."

The final two instruments NASA's sending up with the mission include the near-infrared volatiles spectrometer system, or NIRVSS, and the linear energy transfer spectrometer, or LETS.

"NIRVSS is a suite of sensors that includes a near infrared spectrometer, a Thermal Radiometer and a high resolution seven color imager," Watkins said. "These sensors will make observations of the lunar surface to determine the surface composition, the fine scale and morphology and the thermal environment."

In other words, NIRVSS will help the team understand how those aforementioned volatiles may be diffused across the lunar surface — including whatever volatiles are created by the lander itself — and reveal how surface temperatures affect the substances.

LETS, on the other hand, is going to shine off the lunar surface, when the lander is still cruising in the moon's orbit. It's a radiation monitor that can measure the environment to help scientists learn what solar particle events might be occurring mid-flight. This is particularly important because if humans are to dwell in lunar orbit for long durations like NASA imagines, or even on the lunar surface, it'll be key to know what protection they'll need to wear to prevent too much exposure to radiation.

Together, these instruments will dissect features near the landing site known as "Gruithuisen Domes" that scientists are interested in because they represent volcanic flows on the moon, or "Mare volcanism."

"Characterizing the emplacement history of these Gruithuisen Domes relative to episodes of Mare volcanism is a really important component of understanding the entire history of the region," Watkins said.

But beyond NASA payloads, there are 15 more goodies getting sent to the moon. And while many of them are super scientific like the German Aerospace Center's M-42 radiation detector, quite a few are fun mementos that remind us of the humanity behind human space exploration.

Japan's Lunar Dream capsule, courtesy of the company Astroscale, is a timecapsule that'll be onboard with messages from over 80,000 children around the world. The U.S.'s Elysium Space is sending the remains of peoples' loved ones to create lunar memorials. And scientists from Seychelles are sending one bitcoin.

"We're going to be bringing seven nations to the surface of the moon, six of which have not touched down software on the surface of the moon, including the UK, Mexico, Germany, Hungary, Japan, and Seychelles," John Thornton, the CEO of Astrobiotic said. "We actually made our first commercial payload sale for lunar delivery, and I believe it might have been one of the first in the world, back in 2014. And, since then, we've been collecting payload customers and building up the manifest for this mission."

"If you're a lunar scientist, you might have to wait your entire career to have one opportunity to fly an instrument on a planetary mission," he said. "CLPS and this partnership with NASA affords the opportunity for our nation's scientists to regularly touch the surface of the moon, multiple times in their careers, and have a campaign of tests and results."

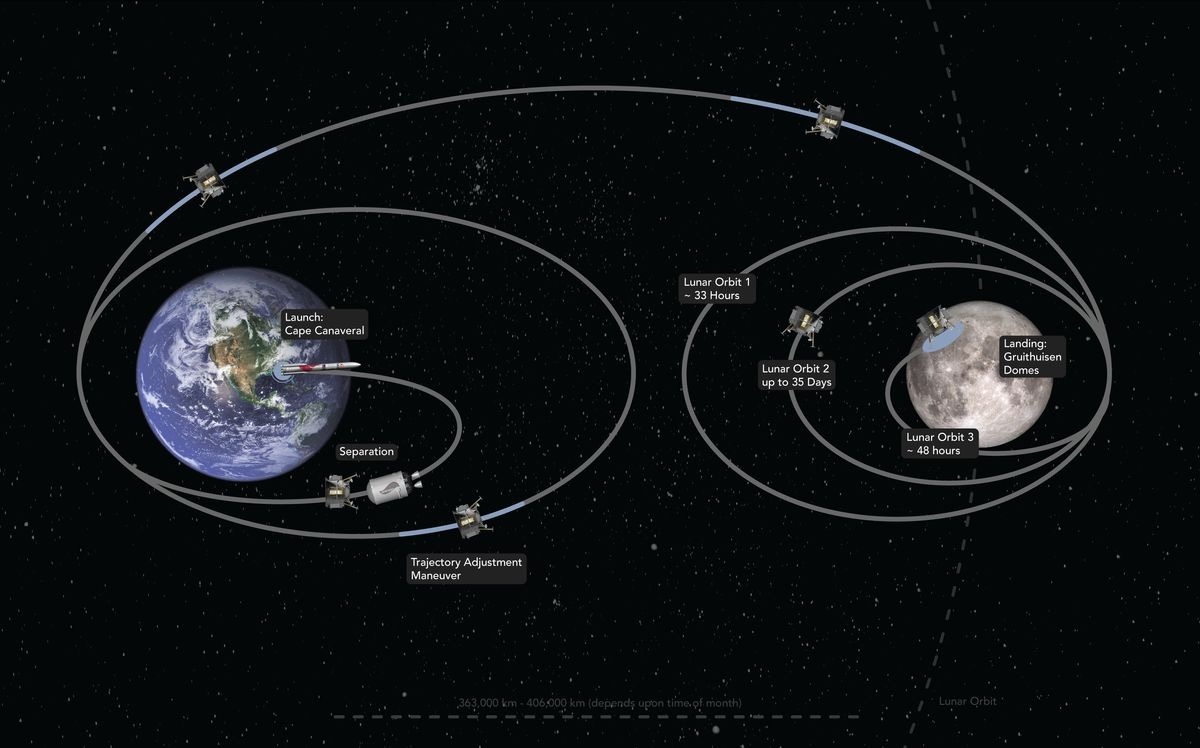

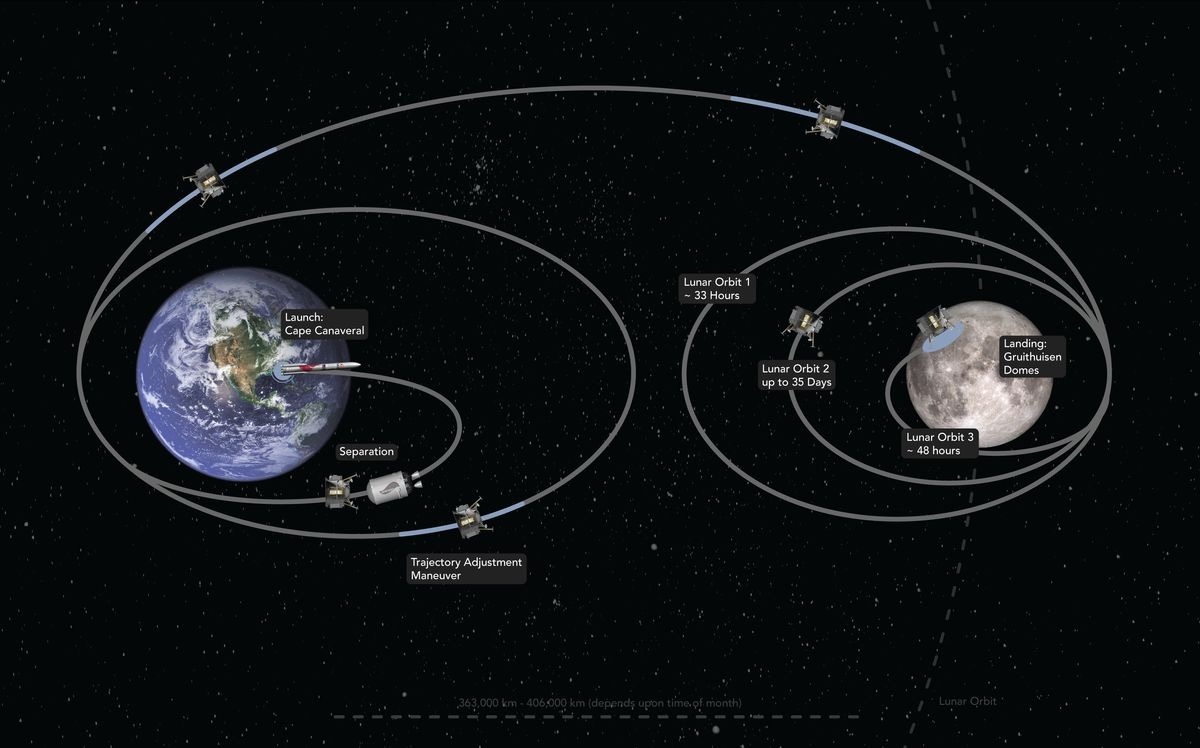

As to how exactly Peregrine will get to the moon, here's what the team says will go down.

Getting there

Liftoff is currently scheduled for around 1:50 a.m. ET on Dec. 24, the team says, with rain dates falling on the two following days. If launch does happen during this window, the lander is expected to touch down on the lunar surface on Jan. 25 of next year.

"You've seen China, and more recently, India successfully landed on the moon in the last decade," Chris Culbert, project manager for CLPS at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, said. "But today, no private company has successfully landed on the moon. Landing on the moon is a daunting technical challenge, particularly for robotic vehicle engines, navigation systems, radios, and many other social systems all have to work together to enable a soft landing."

After launch, the launch vehicle and spacecraft (still connected) will get directly into a maneuver called a translunar injection, meaning it'll still be close to Earth but on a trajectory that essentially intersects with the moon's orbit. Within an hour or so of launch, the spacecraft will officially separate from its launch vehicle, and the team will start communicating with the lander and making small maneuvers to make sure the path looks okay.

"This will be actually the first time we're firing our engines as a system," Thornton said. "We've of course, fired them individually here on Earth, but this will be the first time it's been all together as a spacecraft, because you simply can't test that here on Earth."We'll be doing at least one, potentially up to three, of those trajectory correction maneuvers, and that's dependent on the precision of the initial launch."

Then, about 12 days later, the spacecraft will reach lunar orbit.

Illustration of Peregrine's flight path from Earth to the moon. (Image credit: Astrobiotic)

"We're gonna go to a medium orbit and stay in that orbit for a little while, while we wait for the local lighting conditions to align," Thornton said. "Most of the time between launch and landing is actually waiting for the local lighting to be correct. So basically, we're trying to land at a specific spot on the moon, at a specific time in the morning."

Once everything looks good, the spacecraft will lower onto the surface at the designated landing site. The lander will operate for about 10 days before the sun sets, leading to the same lunar night that saw India's Chandrayaan-3 lander fade away.

"It'll go from a relatively warm 100 to 120 degrees Celsius down to liquid nitrogen cold," Thornton said. "It will stay that way for two weeks, and typically with the temperatures in that range, there's lots of things that break."

"Yes, it's Christmas Eve," he said, "but it will be one heck of a Christmas present."

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 20.12.2023

.

Astrobotic ready to launch Peregrine lunar lander in early January

Image Credits: Astrobotic

Astrobotic’s first lunar lander is ready for lift-off.

The company announced Tuesday that the lander, called Peregrine, has completed final checkouts and fueling after it was mated with United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket last month. All that’s left now is launch on January 8 — followed, of course, by a historic lunar landing.

“If you’ve been following the lunar industry, you understand landing on the Moon’s surface is incredibly difficult,” Astrobotic CEO John Thornton said in a statement. “With that said, our team has continuously surpassed expectations and demonstrated incredible ingenuity during flight reviews, spacecraft testing, and major hardware integrations.”

“We are ready for launch, and for landing.”

The nearly two-meter tall Peregrine lander will be carrying 20 payloads for government and commercial customers. The lander, which has a payload capacity of 90 kilograms, will operate for around 192 hours after it touches down on the lunar surface. During that time, it will provide power and communications to the payloads. According to a payload user’s guide on Astrobotic’s website, the company is charging about $1.2 million per kilogram of mass delivered to the lunar surface.

Astrobotic is executing the mission as part of a $79.5 million contract from NASA under the agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. The company was also awarded a second CLPS contract for its much larger Griffin lander; that mission is expected to launch in late 2024.

Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic is one of a handful of commercial players betting that there will be a thriving market for lunar payload delivery services. Other companies include Intuitive Machines, which is aiming to launch its first lander just days after Peregrine, on January 12, as well as Firefly Aerospace and Japanese firm ispace, which had a failed lunar launch earlier this year.

After Peregrine lifts off from Cape Canaveral in Florida, the spacecraft will execute a series of burns to get it into position to touch down on the moon on February 23.

Astrobotic is not the only company with much on the line with January 8’s launch: The mission also marks the first-ever flight of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket, a vehicle that has been beset by delays that have subsequently pushed back its debut by years. ULA aims to launch several Vulcan flights next year, and eventually needs to complete a multi-billion-dollar 38-launch deal with Amazon for its Project Kuiper satellite broadband constellation.

Astrobotic and ULA were originally targeting a December 24 launch date, but that was later delayed to give ULA time to complete a wet dress rehearsal. That wet dress was finally finished on December 14, ULA said.

Quelle: TechCrunch

----

Update: 27.12.2023

.

Private companies prepare for first American Moon landing in decades

The first two private American Moon missions are set to launch in January and February 2024. NASA science is hitching a ride with American-made lunar landers.

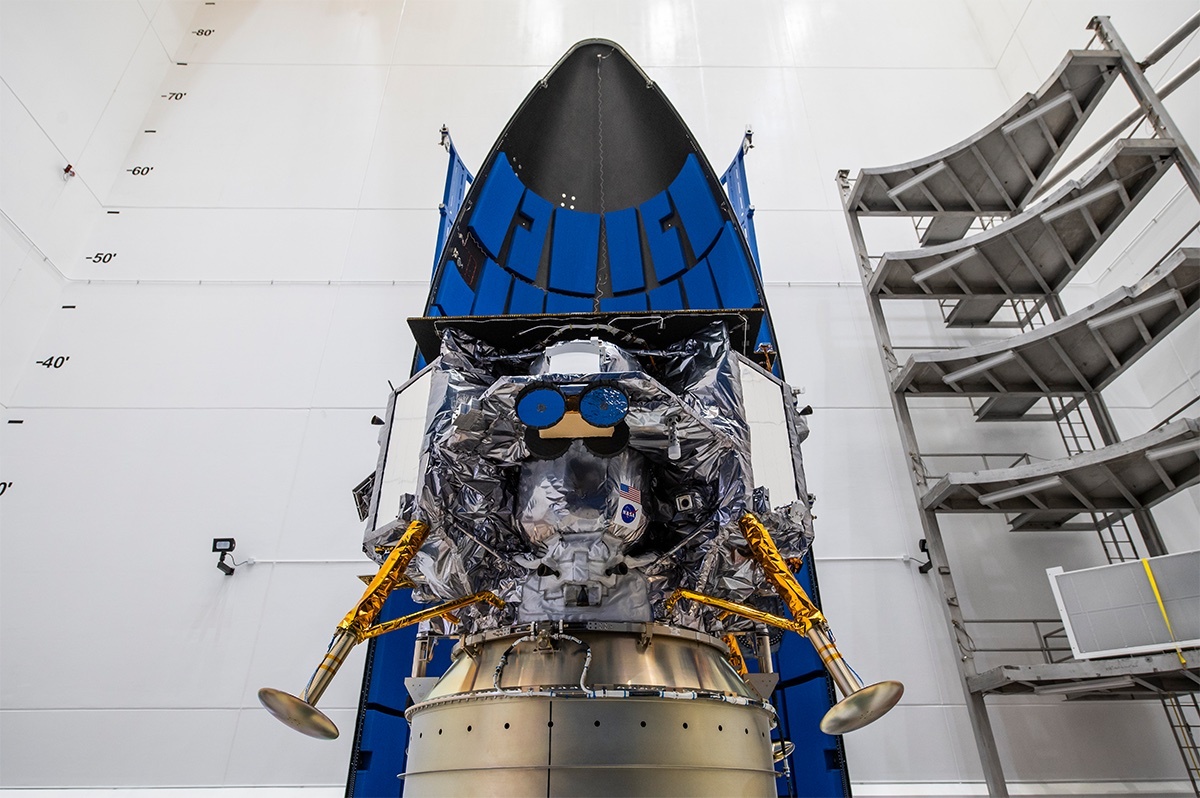

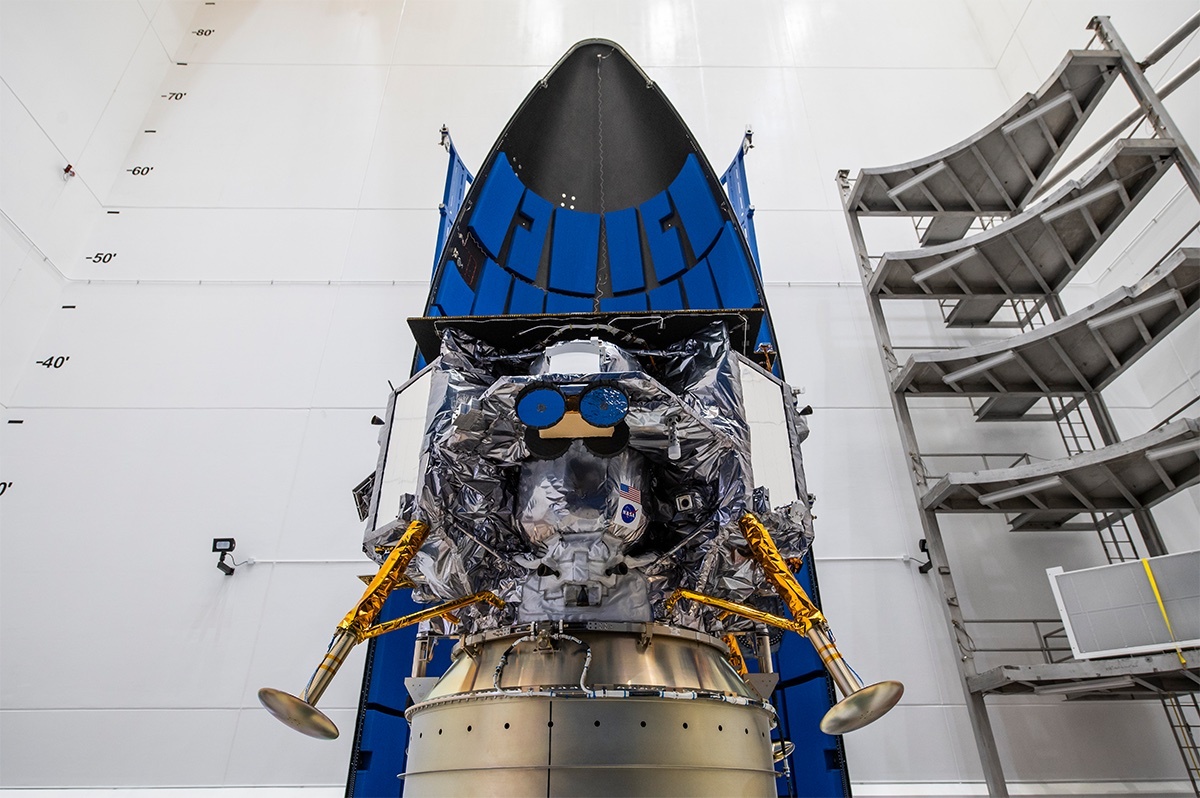

Astrobotic Peregrine lander integrated with ULA's Vulcan rocket fairing. (Image: ULA)

(ULA)

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – Two Moon landers carrying NASA science are set to launch from Florida in early 2024, setting up either of the robotic missions to possibly be the first of a private company to land on the Moon.

The missions are part of NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, selected to deliver science ahead of the first Artemis astronaut missions to the lunar south pole in late 2025. More than a dozen American companies were awarded contracts with NASA to carry science and technology to the Moon under CLPS.

After several delays in 2023, the first two private missions are set to launch in January and February 2024.

Pittsburgh space company Astrobotic is targeting the launch of its Peregrine Moon lander no earlier than Jan. 8 with United Launch Alliance. The liftoff will be the first mission for ULA's new Vulcan rocket.

MYSTERIOUS NEVER-BEFORE-SEEN DEEP SPACE RADIO SIGNAL FOUND BEYOND MILKY WAY

Astrobotic CEO John Thornton said in November the company accepts the risk of launching with a new vehicle but was comforted by ULA's "stellar track record of success." Much of the Vulcan is based on ULA's workhorse rocket, the Atlas V, with some new improvements and the addition of engines from Blue Origin.

"The vehicle has a new name, but much of the vehicle is actually the Atlas V. So it's a well-proven vehicle in that sense," Thornton said. "Yes, this one has got some new engines and other pieces to it, but we are very confident on that launch."

Even with the confidence in ULA, Thornton said he will be "on the edge of his seat on that launch."

Peregrine will provide power and communication to more than 20 lunar payloads, including five science missions for NASA and science for universities, government and private customers. The different science objectives are catered to the landing zone, a region of ancient basaltic lava flows.

A launch time for Jan. 8 has not been set for the lunar mission lifting off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

Houston-based Intuitive Machines will launch its Nova-C lander with SpaceX on the IM-1 mission in February. The mission was slated to launch in January, within a week of Astrobotic's mission, but in late December, Intuitive Machines said the first available launch window is now in mid-February.

"In coordination with SpaceX, the launch of the Company’s IM-1 lunar mission is now targeted for a multi-day launch window that opens no earlier than mid-February 2024. The updated window comes after unfavorable weather conditions resulted in shifts in the SpaceX launch manifest," Intuitive Machines said.

When it does happen, the IM-1 mission will deliver NASA and other customer science payloads to the lunar south pole for a two-week mission. The lander will also carry a piece of art by Jeff Koons that will remain on the Moon.

Intuitive Machines recently revealed the lander will be called Odysseus in reference to a "long and adventurous journey marked by challenges and trials." The name was chosen after an employee vote.

No private company has successfully landed on the Moon, and either of these companies could become the first.

Since the dawn of the space age, just over half of lunar landing attempts have been successful. In August, India became the fourth nation to land a robotic mission on the Moon after the country's first try failed last year.

Astrobotic's Peregrine Moon lander at Astrotech facilities in Florida. (Image: ULA)

(ULA)

"Landing on the moon is a daunting technical challenge, particularly for robotic vehicles," NASA CLPS manager Chris Culbert told reporters in November. "Engines, navigation systems, radios and many other subsystems all have to work together to enable a soft landing. I mean, to do it without human intervention. We witnessed a lot of robotic landing attempts that didn't get all, we didn't get all these systems to work properly, and they ultimately failed."

Culbert said Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines have used "innovated solutions" to manage risks during the missions. However, the space agency leadership accepts that some CLPS missions may fail.

If Astrobotic's mission launches with ULA on Jan. 8, the lander will touch down on Feb. 23.

Quelle: FOX Weather

----

Update: 30.12.2023

.

NASA Sets Coverage for ULA, Astrobotic Artemis Robotic Moon Launch

Ahead of launch as part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative, Astrobotic’s Peregrine lunar lander is encapsulated in the payload fairing, or nose cone, of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket on Nov. 21, 2023, at Astrotech Space Operations Facility near the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Launch of Astrobotic’s Peregrine Mission One will carry NASA and commercial payloads to the Moon in early 2024 to study the lunar exosphere, thermal properties, and hydrogen abundance of the lunar regolith, magnetic fields, and the radiation environment of the lunar surface.

United Launch Alliance

As part of NASA’s CLPS (Commercial Lunar Payload Services) initiative and Artemis program, United Launch Alliance (ULA) and Astrobotic are targeting 2:18 a.m. EST Monday, Jan. 8, for the first commercial robotic launch to the Moon’s surface. Carrying NASA science, liftoff of ULA’s Vulcan rocket and Astrobotic’s Peregrine lunar lander will happen from Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida.

Live launch coverage will air on NASA+, NASA Television, the NASA app, and the agency’s website, with prelaunch events starting Thursday, Jan. 4. Learn how to stream NASA TV through a variety of platforms including social media. Follow events online at: https://www.nasa.gov/nasatv.

Peregrine will land on the Moon on Friday, Feb. 23. The NASA payloads aboard the lander aim to help the agency develop capabilities needed to explore the Moon under Artemis and in advance of human missions on the lunar surface.

Full coverage of this mission is as follows (all times Eastern):

Thursday, Jan. 4

11 a.m. – Science media briefing via WebEx with the following participants:

- Paul Niles, CLPS project scientist, NASA Headquarters

- Chris Culbert, CLPS program manager, NASA’s Johnson Space Center

- Nic Stoffle, science and operations lead for Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer, NASA Johnson

- Anthony Colaprete, principal investigator, Near-Infrared Volatile Spectrometer System, NASA’s Ames Research Center

- Richard Elphic, principal investigator, Neutron Spectrometer System, NASA’s Ames Research Center

- Barbara Cohen, principal investigator, Peregrine Ion-Trap Mass Spectrometer, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

- Daniel Cremons, deputy principal investigator for Laser Retroreflector, NASA Goddard

- Niki Werkheiser, director, Technology Maturation, Space Technology Mission Directorate, NASA Headquarters

Video of the teleconference will stream live on the agency’s website: https://www.nasa.gov/nasatv.

Media may ask questions via WebEx. For the dial-in information, please contact the Kennedy newsroom no later than 10 a.m. on Jan. 4, at: ksc-newsroom@mail.nasa.gov.

Friday, Jan. 5

3 p.m. – Lunar delivery readiness media teleconference with the following participants:

- Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for Exploration, Science Mission Directorate, NASA Headquarters

- Ryan Watkins, program scientist, Exploration Science Strategy and Integration Office, NASA Headquarters

- John Thornton, CEO, Astrobotic

- Gary Wentz, vice president, Government and Commercial Programs, ULA

- Arlena Moses, launch weather officer, Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s 45th Weather Squadron

Audio of the teleconference will stream live on the agency’s website: https://www.nasa.gov/nasatv.

Media may ask questions via phone. For the dial-in number and passcode, please contact the Kennedy newsroom no later than 1 p.m. on Jan. 5, at: ksc-newsroom@mail.nasa.gov.

Monday, Jan. 8

1:30 a.m. – NASA TV launch coverage begins

2:18 a.m. – Launch

NASA launch coverage

Audio only of the news conferences and launch coverage will be carried on the NASA “V” circuits, which may be accessed by dialing 321-867-1220, -1240, or -7135. On launch day, the full mission broadcast can be heard on -1220 and -1240, while the countdown net only can be heard on -7135 beginning approximately at 1:30 a.m. when the mission broadcast begins.

On launch day, a “tech feed” showing a static shot of the launch pad without NASA TV commentary will be carried on the NASA TV media channel.

NASA website launch coverage

Launch day coverage of the mission will be available on the NASA website. Coverage will include live streaming and blog updates beginning no earlier than 1:30 a.m. on Jan. 8, as the countdown milestones occur. On-demand streaming video and photos of the launch will be available shortly after liftoff. For questions about countdown coverage on the Artemis blog for updates.

Attend launch virtually

Members of the public can register to attend this launch virtually. As a virtual guest, you have access to curated resources, schedule changes, and mission-specific information delivered straight to your inbox. Following each activity, virtual guests will receive a commemorative stamp for their virtual guest passport.

Watch, engage on social media

Let people know you’re following the mission on X, Facebook, and Instagram by using the hashtag #Artemis.

In May 2019, NASA awarded a task order for the scientific payload delivery to Astrobotic, which is on track to be one of the first of at least eight CLPS deliveries already planned. Through Artemis, NASA is working with multiple CLPS vendors to send a regular cadence of deliveries to the Moon to perform science investigations, test technologies, and demonstrate capabilities to help NASA explore the Moon before NASA sends the first astronauts to land near the lunar South Pole.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 5.01.2024

.

Astrobotic Readies for Historic Lunar Mission with Ansys Technology

An artist's rendering of Astrobotic's Peregrine lunar lander, equipped with Ansys' advanced simulation technology, after landing on the Moon as part of NASA's Artemis program.

In a significant advancement for lunar exploration, Astrobotic is set to embark on one of the first Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) deliveries to the Moon, utilizing Ansys' (NASDAQ: ANSS) sophisticated simulation solutions. The Peregrine lunar lander, scheduled for a January launch and February landing, will transport 20 payloads from seven countries, aiding NASA's Artemis program in preparing for future human missions on the lunar surface.

The journey to the Moon, fraught with extreme temperatures, unpredictable space weather, and high radiation levels, presents a formidable challenge. Peregrine, to be successful, must withstand these harsh cislunar conditions while remaining light enough for fuel efficiency. Astrobotic, therefore, turned to Ansys' virtual design and mission planning tools to ensure their spacecraft's durability and performance.

Working in collaboration with Ansys Elite Channel Partner, SimuTech Group, Astrobotic leveraged a suite of Ansys solutions to optimize Peregrine's design and performance:

+ Ansys' topology optimization capabilities aided in designing a lander that is up to 20% lighter while maintaining structural integrity.

+ Ansys Mechanical was employed to evaluate Peregrine's resilience under the extreme structural loads of launch and transit, including considerations for shock, vibration, and fluid transients during descent.

+ The design maturity for stress reduction and mass optimization, crucial for assembly, was achieved using Ansys Discovery.

+ Astrobotic used Ansys Thermal Desktop for analyzing diverse thermal environments and trajectory options in the complex cislunar orbit, aiding in optimal launch and landing planning.

Communications integrity is vital as Peregrine ventures further from Earth. Astrobotic implemented Ansys HFSS for designing the antenna radiation patterns, ensuring robust signal strength for communications and orbit trajectory tracking.

Sharad Bhaskaran, mission director at Astrobotic, highlighted the crucial role of Ansys solutions, stating, "Ansys solutions helped us design and validate an innovative lander within a strict mission timeline that a manual approach would not have met." Bhaskaran emphasized the rigorous testing to ensure Peregrine's durability, crediting expert engineering guidance from SimuTech and Space Exploration Engineering for their confidence in the lander's readiness.

Supporting Astrobotic's mission planning, Space Exploration Engineering (SEE) leveraged Ansys' DME capabilities. SEE experts, as part of the Astrobotic Flight Dynamics team, used Ansys Systems Tool Kit (STK) and Orbit Determination Tool Kit (ODTK) for mission trajectory planning and tracking. SEE's contribution, particularly through the AstroFDS flight dynamics system, provided crucial automation and configuration control, enhancing mission capabilities.

John Carrico Jr., owner and chief technology officer of Astrogator and technical advisor at SEE, underscored the complexity of lunar missions, noting, "Our collaboration with Ansys helps customers like Astrobotic account for cislunar environments through predictively accurate, reliable simulations and real-time guidance from experts with a track record of success."

Shane Emswiler, senior vice president of products at Ansys, lauded the Peregrine lander as a pathfinder for the CLPS missions. He stressed the indispensability of Ansys' simulation solutions in ensuring predictable performance in the hostile lunar environment, a task unachievable with Earth-based physical testing alone. Ansys' history of providing reliable simulation solutions across various sectors, including civil, defense, and commercial space programs, has been a cornerstone in managing uncertainties in space missions.

Quelle: SD

----

Update: 5.01.2024

.

NASA instruments set to fly on Peregrine commercial lunar lander

Astrobotic’s Peregrine lunar lander is scheduled to launch Jan. 8 on the first Vulcan Cenatur. Credit: ULA

WASHINGTON — As NASA prepares for the first launch of a commercial lunar lander carrying agency-sponsored payloads, it is trying to balance the science it can achieve with the challenges of landing on the moon and other emerging concerns.

United Launch Alliance said Jan. 4 that it has completed the launch readiness review for the inaugural flight of its Vulcan Centaur rocket, a mission designated Cert-1. That review confirmed a planned launch at 2:18 a.m. Eastern Jan. 8, with an 85% chance of acceptable weather.

The primary payload of Cert-1 is Peregrine, a commercial lunar lander developed by Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic. The launder is carrying 20 payloads, including five instruments from NASA under a Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) award made in 2019.

Three of the instruments — the Near-Infrared Volatile Spectrometer System (NIRVSS), Neutron Spectrometer System (NSS) and Peregrine Ion-Trap Mass Spectrometer (PITMS) — will work together to study volatiles like water on the surface and the moon’s exosphere.

“We don’t expect natural water at this Peregrine landing location,” said Richard Elphic, principal investigator for NSS at NASA’s Ames Research Center, in a Jan. 4 media teleconference. The landing location, near the Gruithuisen Domes, is outside of the polar regions thought to harbor water and other ices. “But, the lander will spray-paint the surface with its rocket exhaust during its descent,” which he said includes water that NSS and the other two instruments could detect.

The three instruments working together, he said, “may help us better understand how water molecules migrate and possibly end up at the cold lunar poles.”

Other volatiles that the instruments could detect include carbon dioxide, ammonia and methane, said Tony Colaprete, principal investigator for NIRVSS at NASA Ames. It could also detect sulfur-bearing compounds that can survive higher temperatures. “It will be interesting to see if there is any sulfur at this landing site,” he said, citing the detection of sulfur by India’s Chandrayaan-3 mission last year at a latitude of about 70 degrees south.

“We’re very interested in understanding the decay of the hydrazine plume from the descent engines,” said Barbara Cohen, principal investigator for PITMS at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. That instrument can also detect a range of volatiles as well as noble gases in the exosphere.

A fourth instrument, the Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer, will take radiation measurements during the lander’s cruise to the moon and in orbit around it as well as after landing. A fifth instrument, the Laser Retroreflector Array, is a passive instrument designed to support ranging measurements of the lander and is similar to retroreflectors flown on other landers, including those from other space agencies.

NASA had planned to fly up to 10 instruments on Peregrine, but last year NASA removed five of them. Agency officials said at a Nov. 29 briefing that it removed those experiments because of issues with the performance of the lander and the descent engines available for it.

At this briefing, Chris Culbert, NASA CLPS program manager, said the agency was balancing the science it wants to do with early lander missions with demonstrating that the landers can safely make it to the surface.

“These early missions have some clear science opportunities, but we weren’t being driven by specific science strategies until we were reasonably confident that the marketplace could actually deliver and land on the moon softly,” he said. Later CLPS missions will have more complex science objectives, he added.

There is also uncertainty about the business case for commercial lunar landers. “I don’t think it’s all that clear, certainly to us at NASA,” what markets will drive demand for such landers, he said. “I think you’ll see that evolve quite a bit over time, but the first step is a successful landing.”

Navajo Nation concerns

Besides the five NASA instruments, Peregrine is carrying payloads from a wide range of companies and organizations, including national space agencies. Among them are items from Celestis and Elysium Space, two companies that offer to take samples of cremated remains to space as a memorial.

Those payloads have prompted sharp criticism from the Navajo Nation, which views placing human remains on the moon an act of desecration. The president of Navajo Nation, Buu Nygren, said last month he asked NASA to delay the launch because of those payloads, citing an agreement after the Lunar Prospector mission in 1998, which carried the ashes of planetary science Eugene Shoemaker. NASA, responding to criticism from Navajo Nation then, said it would consult with them before any future missions.

At the Jan. 4 briefing, Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said the agency did receive a letter from Navajo Nation requesting a “tribal consultation” about those payloads. The letter also went to the Department of Transportation, which includes the Federal Aviation Administration, the agency that licenses commercial launches.

“An intergovernmental team is currently looking into this in more detail,” he said, including setting up a meeting with Navajo Nation officials. He said the agency could not provide more details about that effort, including when that meeting may take place.

It is unclear that NASA could do anything about those payloads, though, since they are flying on a commercial lander rather than a NASA-led mission. “These are commercial missions. We don’t have the framework for telling them what they can and can’t fly,” Culbert said. Any such approval would likely come from the FAA though the payload review that is part of the launch licensing process, he said.

Commercial lunar landers “is a totally new industry, and it is an industry where everyone is learning as we have set this up over the last few years,” Kearns added. “We take concerns like the ones expressed by the Navajo Nation very, very seriously, and we think we’re going to be continuing this conversation.”

Quelle: SN