18.11.2022

Ready to chase comets? We look at two fuzzy solar system travelers that will keep you on your toes all fall and winter long.

On October 30, 2022, Comet ZTF E3 displayed a blue-green coma, compact nuclear region and two tails — a curved, yellow dust tail and a very faint ion tail pointing straight up from the comet's head.

Eduard Demencik

Every comet bright enough to see in one of my too-many telescopes is like a child I have the privilege of watching grow up. Some start their apparitions at a crawl, barely budging from night to night. A month later, they're clipping along at 5° or more a day. While astronomers are good at predicting cometary behavior, surprises happen. Comets crumble, undergo explosive outbursts, fail to brighten, and occasionally "birth" baby comets. Constant change combined with a bent toward capriciousness make these fuzzy solar system-trotters irresistible targets for amateurs.

That's why I try to follow them from start to finish through stasis and upheaval. Like watching a pair of birds build a nest and raise a family, the raw experience of natural behavior is positively exhilarating. "Look deep into nature," Einstein said, "and you will understand everything better."

ZTF2

There are two 10th-magnitude comets now visible in the evening sky, both discovered by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) and bear its name — Comet ZTF (C/2020 V2) and Comet ZTF (C/2022 E3). The survey scans the entire northern sky every two nights using an exceptionally wide-field CCD camera on the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory. Among its quarry are near-Earth asteroids, thousands of supernovae (6,600 classified to date), and numerous comets including our two featured objects. Both are slowly brightening and will grace the skies for months, making them ideal subjects to watch evolve.

Dan Bartlett

I've been tracking the ZTF pair for some time now. Before clouds and moonlight temporarily stole them away I observed C/2020 V2 on October 25th at magnitude 10.8 near the Bowl of the Big Dipper through my 15-inch Dob. Its well-condensed coma measured 1′ across with a smear of tail pointing east detected with averted vision. Photographically, it resembled a tadpole.

LONG-TERM VISITOR

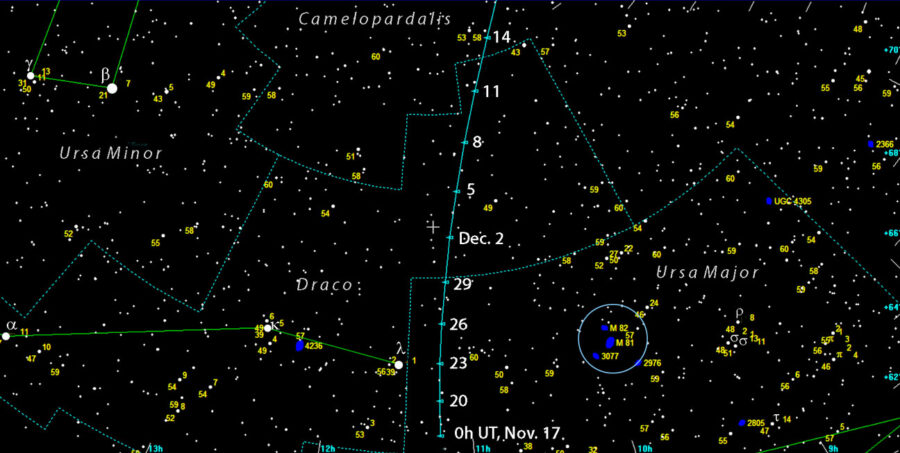

Comet ZTF V2 still hovers around magnitude 10.5 as it inches north in the direction of Polaris at a current rate of about ½° per day. In mid-November the comet stands about 20° high at nightfall for observers at mid-northern latitudes and is circumpolar for much of the U.S. and Europe. Maximum altitude occurs just before dawn. An 8-inch or larger telescope under moonless skies should provide a good view of this compact cotton wad.

MegaStar courtesy of Emil Bonnano

C/2020 V2 pole-vaults from Ursa Major to Sculptor between now and next October, slowly brightening to a peak magnitude of about 9.0–9.5 in late January and again in late August–early September during its closest approach to Earth on September 17, 2023. Along the way it gives the North Star a nod, passing 3.7° to its southeast on December 22nd and 0.8° west of the bright open cluster M103 in Cassiopeia on January 25th and 26th. I'm as eager to see these encounters and others as well as watch for changes in the comet's tail length and nuclear region during its lengthy apparition.

Dan Bartlett

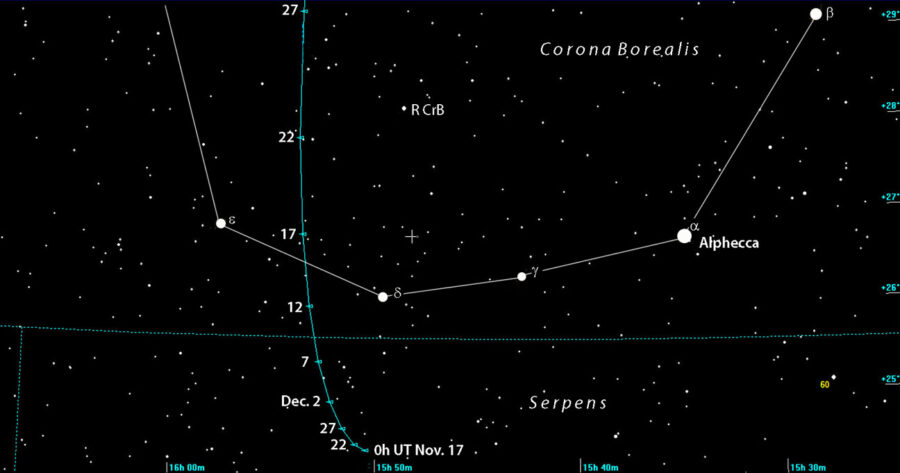

Comet ZTF (C/2022 E3) should become an order of magnitude more spectacular than its doppelgänger namesake. Staying put for now in northern Serpens near the Corona Borealis border, this small, strongly condensed comet glows around magnitude 9.8. I first mined it from the Milky Way back in June not far from Albireo at magnitude 13.8 with a coma only about 30″ across. Even then it bore the signature appearance of a comet with a bright nucleus (relatively speaking) and tiny, fan-shaped tail. I made my most recent observation on November 1st in first-quarter moonlight with Comet ZTF E3 low in the northwestern sky. More vibrant now at magnitude 10, the coma had grown to about 1.5′, and I could tease out a 3′ tail pointing east.

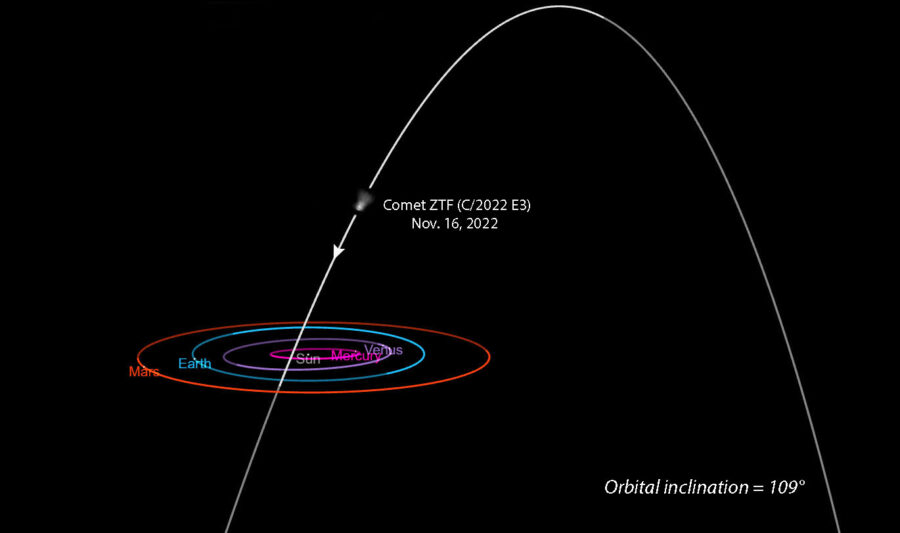

NASA HORIZONS

Due to orbital geometry, the comet waddles northward at a tortoise's pace while simultaneously sinking lower and lower in the northwestern sky. You still have time to spot it the end of evening twilight, but not for long. Before you bite your nails, here's the good news. At the same time E3 departs the evening sky at month's end, it turns up in the northeastern sky before dawn — a rare instance of near-perfect astronomical timing. By Thanksgiving on November 24th the comet is situated a lusty 20° high at the start of morning twilight.

NAKED-EYE THIS JANUARY?

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

Come January 1st, Comet ZTF E3 quickly accelerates, crossing from Corona Borealis into Boötes, Draco, and Ursa Minor while brightening from magnitude 8 to 5–5.5 by month's end. During the third week of January it becomes circumpolar for mid-northern latitude observers and passes about 10° southeast of Polaris on January 29th. On the night of February 10–11 it pays a visit to Mars. Their separation tightens from about 1.5° during the early evening hours (comet northeast of Mars) to just under 1° before the planet sets. Before this cosmic snowball exits Taurus it buzzes past the Hyades from February 13–15.

MegaStar courtesy of Emil Bonnano

Perihelion occurs on January 12th at 1.1 astronomical units, and closest approach to the Earth on February 1st at 0.29 a.u. Peaking at around magnitude 5 in late January and early February, it should be a fine binocular object and likely visible with the unaided eye from dark, moonless skies — just the motivation we need for getting outside on frigid nights.

BLAZAR BLAST!

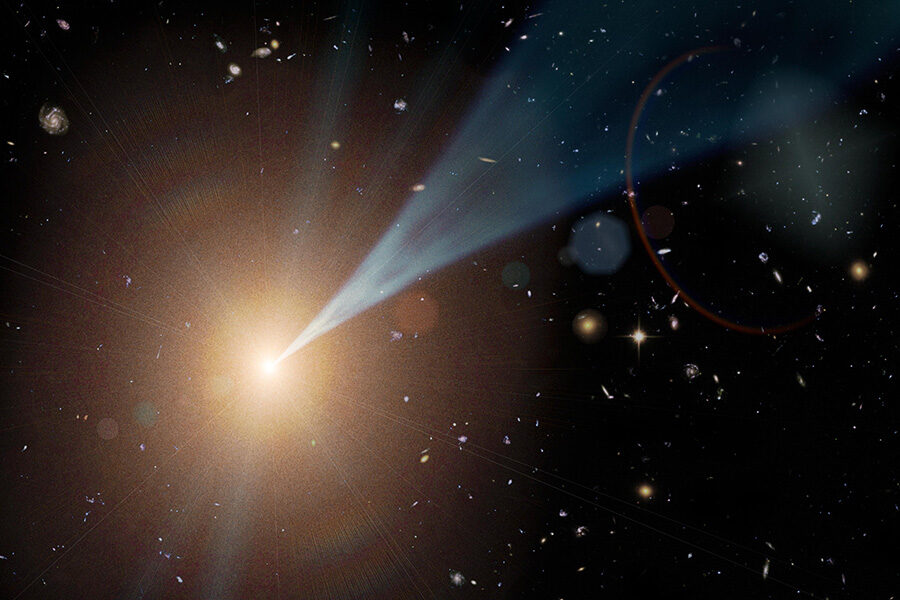

NASA / JPL-Caltech

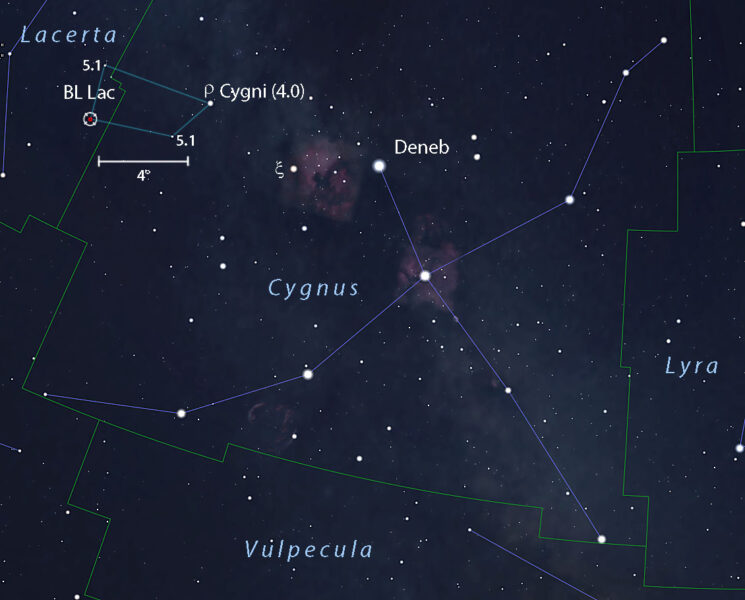

Although this has absolutely nothing to do with comets, the blazar BL Lacertae (BL Lac), first classified as a variable star, is currently undergoing a major flare. Typically around magnitude 14, it shot up to 12.5 in mid-October and rose further to 12.0 later that month. I estimated its magnitude at 12.3 on November 12.2 UT, making it bright enough to spot in apertures as small as six inches from a dark sky. This dramatic outburst is even brighter than its previous flare in August 2020. (Update November 16th: BL Lac has faded to about 12.8, so an 8-inch telescope might be required.)

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

A blazar is basically a quasar — a supermassive black hole that gobbles up gas in the center of a galaxy. As the material goes down the chute, it heats up and radiates an ungodly amount of energy, much of it beamed as jets of particles and radiation at near-light speed from its poles. Viewed from the side, it's a quasar. But when a jet faces the Earth and we stare directly down the barrel of the gun, it's a blazar. American astronomer Edward Spiegel coined the term in 1978 by combining the "bl" from BL Lac, the first discovered and prototype, with quasar. At 900 million light-years away it might just be one of the farthest things you'll ever see.

Keep watch on BL Lac, and I guarantee you'll see its brightness fluctuate with the help of the comparison stars on the accompanying AAVSO wide-field and narrow-field finder charts. Thank your lucky stars it's too far away to give our planet a serious sunburn!