1.10.2022

NASA’s Juno Shares First Image From Flyby of Jupiter’s Moon Europa

Observations from the spacecraft’s pass of the moon provided the first close-up in over two decades of this ocean world, resulting in remarkable imagery and unique science.

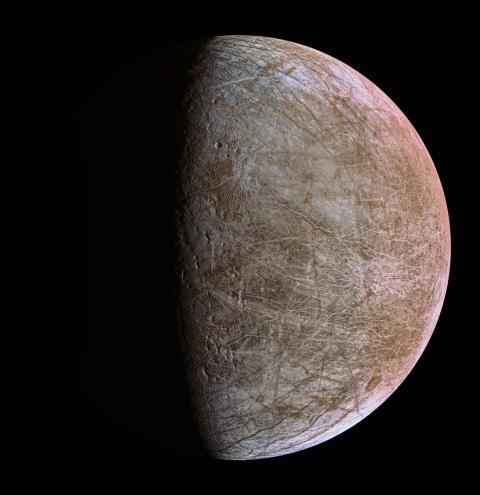

The complex, ice-covered surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa was captured by NASA’s Juno spacecraft during a flyby on Sept. 29, 2022. At closest approach, the spacecraft came within a distance of about 219 miles (352 kilometers).

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SWRI/MSSS

The first picture NASA’s Juno spacecraft took as it flew by Jupiter’s ice-encrusted moon Europa has arrived on Earth. Revealing surface features in a region near the moon’s equator called Annwn Regio, the image was captured during the solar-powered spacecraft’s closest approach, on Thursday, Sept. 29, at 2:36 a.m. PDT (5:36 a.m. EDT), at a distance of about 219 miles (352 kilometers).

This is only the third close pass in history below 310 miles (500 kilometers) altitude and the closest look any spacecraft has provided at Europa since Jan. 3, 2000, when NASA’s Galileocame within 218 miles (351 kilometers) of the surface.

Europa is the sixth-largest moon in the solar system, slightly smaller than Earth’s moon. Scientists think a salty ocean lies below a miles-thick ice shell, sparking questions about potential conditions capable of supporting life underneath Europa’s surface.

This segment of the first image of Europa taken during this flyby by the spacecraft’s JunoCam (a public-engagement camera) zooms in on a swath of Europa’s surface north of the equator. Due to the enhanced contrast between light and shadow seen along the terminator (the nightside boundary), rugged terrain features are easily seen, including tall shadow-casting blocks, while bright and dark ridges and troughs curve across the surface. The oblong pit near the terminator might be a degraded impact crater.

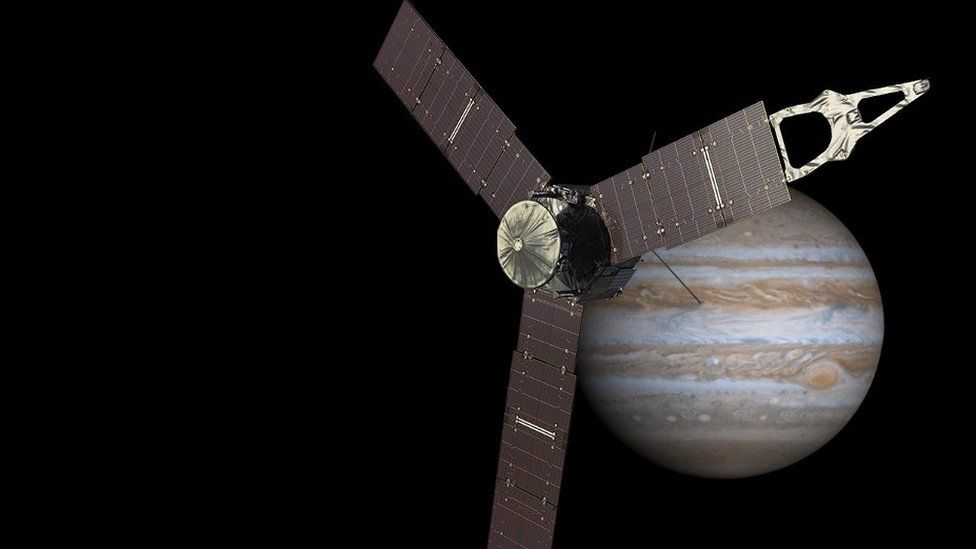

Find out where Juno is right now with NASA’s interactive Eyes on the Solar System. With its blades stretching out some 66 feet (20 meters), the spacecraft is a dynamic engineering marvel, spinning to keep itself stable as it orbits Jupiter and flies by some of the planet’s moons. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

With this additional data about Europa’s geology, Juno’s observations will benefit future missions to the Jovian moon, including the agency’s Europa Clipper. Set to launch in 2024, Europa Clipper will study the moon’s atmosphere, surface, and interior, with its main science goal being to determine whether there are places below Europa’s surface that could support life.

As exciting as Juno’s data will be, the spacecraft had only a two-hour window to collect it, racing past the moon with a relative velocity of about 14.7 miles per second (23.6 kilometers per second).

“It’s very early in the process, but by all indications Juno’s flyby of Europa was a great success,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “This first picture is just a glimpse of the remarkable new science to come from Juno’s entire suite of instruments and sensors that acquired data as we skimmed over the moon’s icy crust.”

During the flyby, the mission collected what will be some of the highest-resolution images of the moon (0.6 miles, or 1 kilometer, per pixel) and obtained valuable data on Europa’s ice shell structure, interior, surface composition, and ionosphere, in addition to the moon’s interaction with Jupiter’s magnetosphere.

“The science team will be comparing the full set of images obtained by Juno with images from previous missions, looking to see if Europa’s surface features have changed over the past two decades,” said Candy Hansen, a Juno co-investigator who leads planning for the camera at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona. “The JunoCam images will fill in the current geologic map, replacing existing low-resolution coverage of the area.”

Juno’s close-up views and data from its Microwave Radiometer (MWR) instrument will provide new details on how the structure of Europa’s ice varies beneath its crust. Scientists can use all this information to generate new insights into the moon, including data in the search for regions where liquid water may exist in shallow subsurface pockets.

Building on Juno’s observations and previous missions such as Voyager 2 and Galileo, NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, slated to arrive at Europa in 2030, will study the moon’s atmosphere, surface, and interior – with a goal to investigate habitability and better understand its global subsurface ocean, the thickness of its ice crust, and search for possible plumes that may be venting subsurface water into space.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 7.10.2022

.

NASA’s Juno Gets Highest-Resolution Close-Up of Jupiter’s Moon Europa

Surface features of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa are revealed in an image obtained by Juno’s Stellar Reference Unit (SRU) during the spacecraft’s Sept. 29, 2022, flyby.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI

Observations from the spacecraft’s pass of the moon provided the first close-up in over two decades of this ocean world, resulting in remarkable imagery and unique science.

The highest-resolution photo NASA’s Juno mission has ever taken of a specific portion of Jupiter’s moon Europa reveals a detailed view of a puzzling region of the moon’s heavily fractured icy crust.

The image covers about 93 miles (150 kilometers) by 125 miles (200 kilometers) of Europa’s surface, revealing a region crisscrossed with a network of fine grooves and double ridges (pairs of long parallel lines indicating elevated features in the ice). Near the upper right of the image, as well as just to the right and below center, are dark stains possibly linked to something from below erupting onto the surface. Below center and to the right is a surface feature that recalls a musical quarter note, measuring 42 miles (67 kilometers) north-south by 23 miles (37 kilometers) east-west. The white dots in the image are signatures of penetrating high-energy particles from the severe radiation environment around the moon.

Juno’s Stellar Reference Unit (SRU) – a star camera used to orient the spacecraft – obtained the black-and-white image during the spacecraft’s flybyof Europa on Sept. 29, 2022, at a distance of about 256 miles (412 kilometers). With a resolution that ranges from 840 to 1,115 feet (256 to 340 meters) per pixel, the image was captured as Juno raced past at about 15 miles per second (24 kilometers per second) over a part of the surface that was in nighttime, dimly lit by “Jupiter shine” – sunlight reflecting off Jupiter’s cloud tops.

Designed for low-light conditions, the SRU has also proven itself a valuable science tool, discovering shallow lightning in Jupiter’s atmosphere, imaging Jupiter’s enigmatic ring system, and now providing a glimpse of some of Europa’s most fascinating geologic formations.

“This image is unlocking an incredible level of detail in a region not previously imaged at such resolution and under such revealing illumination conditions,” said Heidi Becker, the lead co-investigator for the SRU. “The team’s use of a star-tracker camera for science is a great example of Juno’s groundbreaking capabilities. These features are so intriguing. Understanding how they formed – and how they connect to Europa’s history – informs us about internal and external processes shaping the icy crust.”

It won’t just be Juno’s SRU scientists who will be busy analyzing data in the coming weeks. During Juno’s 45th orbit around Jupiter, all of the spacecraft’s science instruments were collecting data both during the Europa flyby and then again as Juno flew over Jupiter’s poles a short 7 ½ hours later.

“Juno started out completely focused on Jupiter. The team is really excited that during our extended mission, we expanded our investigation to include three of the four Galilean satellites and Jupiter’s rings,” said Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “With this flyby of Europa, Juno has now seen close-ups of two of the most interesting moons of Jupiter, and their ice shell crusts look very different from each other. In 2023, Io, the most volcanic body in the solar system, will join the club.” Juno sailed by Jupiter’s moon Ganymede – the solar system’s largest moon – in June 2021.

Europa is the solar system’s sixth-largest moon with about 90% the equatorial diameter of Earth’s moon. Scientists are confident a salty ocean lies below a miles-thick ice shell, sparking questions about the potential habitability of the ocean. In the early 2030s, the NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft will arrive and strive to answer these questions about Europa’s habitability. The data from the Juno flyby provides a preview of what that mission will reveal.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 8.10.2022

.

Citizen Scientists Enhance New Europa Images From NASA’s Juno

Science enthusiasts have processed the new JunoCam images of Jupiter’s icy moon, with results that are out of this world.

This view of Jovian moon Europa was created by processing an image JunoCam captured during Juno’s close flyby on Sept. 29.

Citizen scientists have provided unique perspectives of the recent close flyby of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa by NASA’s Juno spacecraft. By processing raw images from JunoCam, the spacecraft’s public-engagement camera, members of the general public have created deep-space portraits of the Jovian moon that are not only awe-inspiring, but also worthy of further scientific scrutiny.

Citizen scientists have provided unique perspectives of the recent close flyby of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa by NASA’s Juno spacecraft. By processing raw images from JunoCam, the spacecraft’s public-engagement camera, members of the general public have created deep-space portraits of the Jovian moon that are not only awe-inspiring, but also worthy of further scientific scrutiny.

“Starting with our flyby of Earth back in 2013, Juno citizen scientists have been invaluable in processing the numerous images we get with Juno,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Center in San Antonio. “During each flyby of Jupiter, and now its moons, their work provides a perspective that draws upon both science and art. They are a crucial part of our team, leading the way by using our images for new discoveries. These latest images from Europa do just that, pointing us to surface features that reveal details on how Europa works and what might be lurking both on top of the ice and below.”

JunoCam snapped four photos during its Sept. 29 flyby of Europa. Here’s a detailed look:

Europa Up Close

JunoCam took its closest image (above) at an altitude of 945 miles (1,521 kilometers) over a region of the moon called Annwn Regio. In the image, terrain beside the day-night boundary is revealed to be rugged, with pits and troughs. Numerous bright and dark ridges and bands stretch across a fractured surface, revealing the tectonic stresses that the moon has endured over millennia. The circular dark feature in the lower right is Callanish Crater.

Such JunoCam images help fill in gaps in the maps from images obtained by NASA’s Voyager and Galileo missions. Citizen scientist Björn Jónsson processed the image to enhance the color and contrast. The resolution is about 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) per pixel.

Science Meets Art

This pair of images shows the same portion of Europa as captured by the Juno spacecraft’s JunoCam during the mission’s Sept. 29 close flyby. The image at left was minimally processed. A citizen scientist processed the image at right, and enhanced color contrast causes larger surface features to stand out.

JunoCam images processed by citizen scientists often straddle the worlds of science and art. In the image at right, processed by Navaneeth Krishnan, the enhanced color contrast causes larger surface features to stand out more than in the lightly processed version of the image (left). An example of the results can be seen in the lower right of the enhanced image, where the pits and a small block cast notable shadows. Small-scale texturing of the surface in the image needs to be carefully studied to distinguish between features and artifacts from processing, but the image draws us deeper into Europa’s alien landscape.

“Juno’s citizen scientists are part of a global united effort, which leads to both fresh perspectives and new insights,” said Candy Hansen, lead co-investigator for the JunoCam camera at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona. “Many times, citizen scientists will skip over the potential scientific applications of an image entirely, and focus on how Juno inspires their imagination or artistic sense, and we welcome their creativity.”

Fall Colors

This highly stylized view of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa was created by reprocessing an image captured by JunoCam during the mission’s close flyby on Sept. 29.

Citizen scientist Fernando Garcia Navarro applied his artistic talents to create this image. He downloaded and processed an image that fellow citizen scientist Kevin M. Gill had previously worked on, producing a psychedelic rendering he has titled “Fall Colors of Europa.”

The processed image calls to mind NASA’s poster celebrating Juno’s 2021 five-year anniversary of its orbital insertion at Jupiter.

NASA’s groovy celebration of Juno’s five-year anniversary of its orbital insertion at Jupiter.

More Groovy Details About the Flyby

With a relative velocity of about 14.7 miles per second (23.6 kilometers per second), the Juno spacecraft only had a few minutes to collect data and images during its close flyby of Europa. As planned, the gravitational pull of the moon modified Juno’s trajectory, reducing the time it takes to orbit Jupiter from 43 to 38 days. The close approach also marks the second encounter with a Galilean moon during Juno’s extended mission. The mission explored Ganymede in June 2021 and is scheduled to make close flybys of Io, the most volcanic body in the solar system, in 2023 and 2024.

Juno’s observations of Europa’s geology will not only contribute to our understanding of Europa, but also complement future missions to the Jovian moon. NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, set to launch in 2024, will study the moon’s atmosphere, surface, and interior, with a primary science goal to determine whether there are places below Europa’s surface that could support life.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 16.12.2022

.

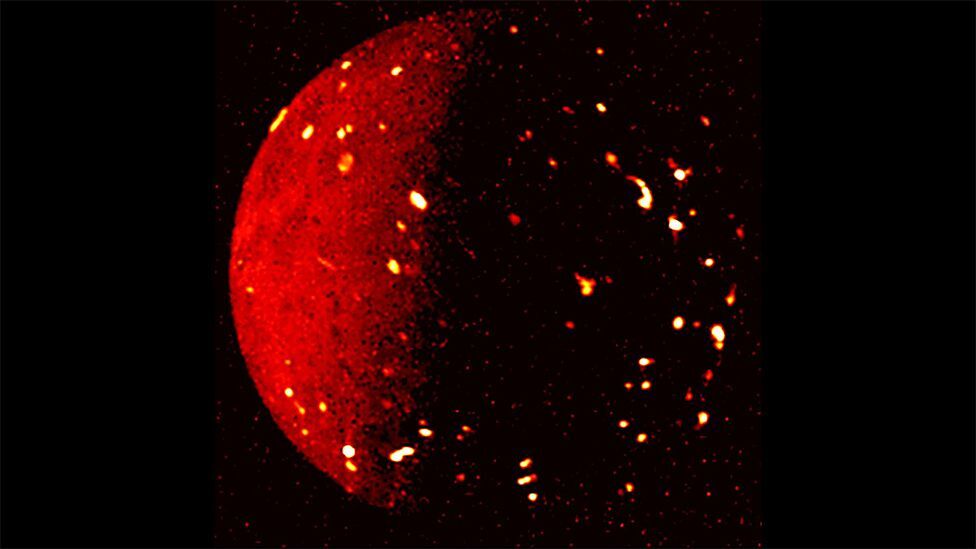

Io volcano world comes into view of Juno probe

This infrared image of Io from 80,000km reveals hotspots: Volcanoes, lava flows and lava lakes

-

Nasa's Juno probe is bearing down on Io, the most volcanically active world in the Solar System.

It's in the process of making a series of ever closer flybys.

Already, the spacecraft has passed by the Jupiter moon at a distance of 80,000km, to reveal details of its hellish, lava-strewn landscape.

But Juno will get much, much nearer to Io over the course of the next year, eventually sweeping over the surface at an altitude of just 1,500km.

It's more than 20 years since we've had such an encounter with the 3,650km-wide object.

"We have a number of objectives besides trying to understand the volcanoes and lava flows, and to map them," said Juno's principal investigator, Dr Scott Bolton from the Southwest Research Institute.

"We're also going to be looking at the gravity field, trying to understand the interior structure of Io, to see if we can constrain whether the magma that's creating all these volcanoes forms a global ocean, or whether it's spotty," he told BBC News.

Io's volcanism is driven by its proximity to Jupiter. It means the moon is subject to immense tidal forces and heating.

Scott Bolton: "Passing Ganymede squeezed and tightened our orbit around Jupiter"

It's a fun time for the Juno mission right now.

Sent primarily to investigate the origin and evolution of Jupiter, Juno has been able to take in bonus observations of the planet's four major moons - Callisto, Ganymede, Europa and now Io.

The spacecraft is picking them off one by one as its orbit around Jupiter narrows.

Fly over Jupiter's northern polar region. Animation produced from Juno imagery by Gerald Eichstädt

It performed its close flyby of Ganymede in 2021, and of Europa earlier this year.

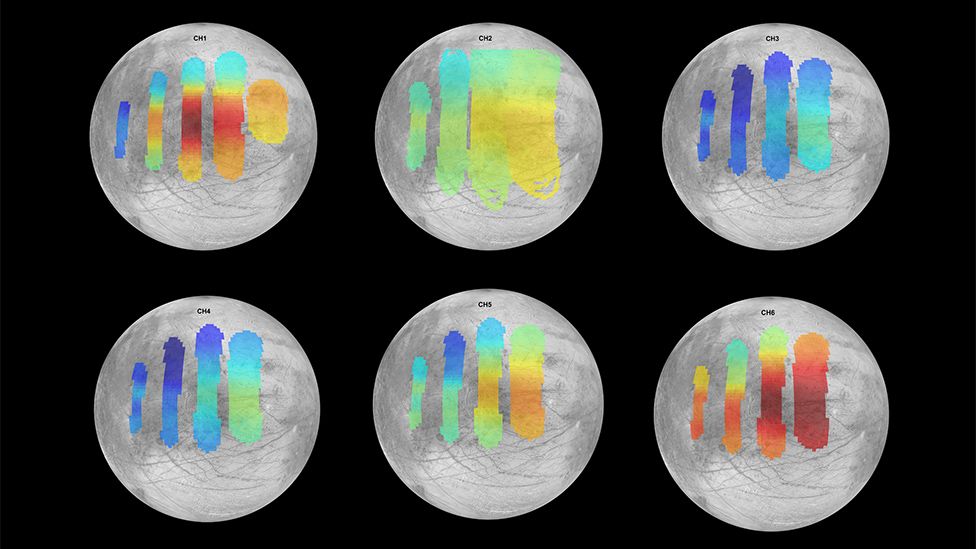

These passes produced some novel insights from Juno's microwave radiometer.

Intended to look deep into the clouds of Jupiter, this instrument has also been able to see down through the ice layers of Ganymede and Europa for tens of kilometres.

These two moons are of particular interest because they're both thought to hide a global ocean of liquid water at depth. The speculation is they might both therefore host some form of life.

Visible images - that's pictures taken at wavelengths of light our eyes would detect - show Ganymede's surface to be a mixture of darker and brighter patches. The brighter areas are younger and colder. Juno's radiometer reveals these zonal differences are not just surface phenomena but are related to structures that have deep roots.

At Europa, the temperatures are lower but vary less from place to place. And interestingly, they become very uniform at depth.

"That may be a hint that you're getting near the liquid," said Dr Bolton. "Because when I get to the liquid, it's going to be completely uniform, because it's going to be like a mirror. It's not crazy to think the water might be just a few kilometres down - six, eight, something like that. I'm not ready to say that's the ocean, but it's conceivable that water is playing a role there."

Watch as Galileo's moons - Callisto, Ganymede, Europa and Io - orbit Jupiter

Lori Glaze, the director of planetary science at Nasa, said she was looking forward to the dedicated missions planned for Jupiter's moons. The European Space Agency's Juice probe will leave Earth next year and will focus its attention on Ganymede. Nasa's Clipper satellite will launch in 2024 and will orbit Europa.

They were very worthy targets, Dr Glaze said.

"Galileo Galilei's discovery of these moons in 1610 marked the birth of modern astronomy," she recalled.

"Up to that point, of course, it was assumed that Earth was the centre of the Universe and everything revolved around us. But when he pointed his telescope at Jupiter, what he saw there didn't fit the paradigm."

Dr Glaze and Dr Bolton were discussing the Juno mission at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in Chicago.

NASA’s Juno Exploring Jovian Moons During Extended Mission

NASA’s Juno mission captured this infrared view of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io on July 5, 2022, when the spacecraft was about 50,000 miles (80,000 kilometers) away. This infrared image was derived from data collected by the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument aboard Juno. In this image, the brighter the color the higher the temperature recorded by JIRAM. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM

After revealing a trove of details about the moons Ganymede and Europa, the mission to Jupiter is setting its sights on sister moon Io.

NASA’s Juno mission is scheduled to obtain images of the Jovian moon Io on Dec. 15 as part of its continuing exploration of Jupiter’s inner moons. Now in the second year of its extended mission to investigate the interior of Jupiter, the solar-powered spacecraft performed a close flyby of Ganymede in 2021 and of Europa earlier this year.

“The team is really excited to have Juno’s extended mission include the study of Jupiter’s moons. With each close flyby, we have been able to obtain a wealth of new information,” said Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “Juno sensors are designed to study Jupiter, but we’ve been thrilled at how well they can perform double duty by observing Jupiter’s moons.”

This animation illustrates how the magnetic field surrounding Jupiter’s moon Ganymede (represented by the blue lines) interacts with and disrupts the magnetic field surrounding Jupiter (represented by the orange lines).

Several papers based on the June 7, 2021, Ganymede flyby were recently published in the Journal of Geophysical Research and Geophysical Research Letters. They include findings on the moon’s interior, surface composition, and ionosphere, along with its interaction with Jupiter’s magnetosphere, from data obtained during the flyby. Preliminary results from Juno’s Sept. 9 flyby of Europa include the first 3D observations of Europa’s ice shell.

Below the Ice

During the flybys, Juno’s Microwave Radiometer (MWR) added a third dimension to the mission’s Jovian moon exploration: It provided a groundbreaking look beneath the water-ice crust of Ganymede and Europa to obtain data on its structure, purity, and temperature down to as deep as about 15 miles (24 kilometers) below the surface.

Visible-light imagery obtained by the spacecraft’s JunoCam, as well as by previous missions to Jupiter, indicates Ganymede’s surface is characterized by a mixture of older dark terrain, younger bright terrain, and bright craters, as well as linear features that are potentially associated with tectonic activity.

“When we combined the MWR data with the surface images, we found the differences between these various terrain types are not just skin deep,” said Bolton. “Young, bright terrain appears colder than dark terrain, with the coldest region sampled being the city-sized impact crater Tros. Initial analysis by the science team suggests Ganymede’s conductive ice shell may have an average thickness of approximately 30 miles or more, with the possibility that the ice may be significantly thicker in certain regions.”

Magnetospheric Fireworks

During the spacecraft’s June 2021 close approach to Ganymede, Juno’s Magnetic Field (MAG) and Jovian Auroral Distributions Experiment (JADE) instruments recorded data showing evidence of the breaking and reforming of magnetic field connections between Jupiter and Ganymede. Juno’s ultraviolet spectrograph (UVS) has been observing similar events with the moon’s ultraviolet auroral emissions, organized into two ovals that wrap around Ganymede.

Credit: Image data: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSSImage processing by Navaneeth Krishnan S CC BY 3.0

“Nothing is easy – or small – when you have the biggest planet in the solar system as your neighbor,” said Thomas Greathouse, a Juno scientist from SwRI. “This was the first measurement of this complicated interaction at Ganymede. This gives us a very early tantalizing taste of the information we expect to learn from the JUICE” – the ESA (European Space Agency) JUpiter ICy moons Explorer – “and NASA’s Europa Clipper missions.”

Volcanic Future

Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanic place in the solar system, will remain an object of the Juno team’s attention for the next year and a half. Their Dec. 15 exploration of the moon will be the first of nine flybys – two of them from just 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) away. Juno scientists will use those flybys to perform the first high-resolution monitoring campaign on the magma-encrusted moon, studying Io’s volcanoes and how volcanic eruptions interact with Jupiter’s powerful magnetosphere and aurora.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 23.12.2022

.

Juno Spacecraft Recovering Memory After 47th Flyby of Jupiter

The science data from the solar-powered spacecraft’s most recent flyby of Jupiter and its moon Io appears to be intact.

NASA’s Juno spacecraft completed its 47th close pass of Jupiter on Dec. 14. Afterward, as the solar-powered orbiter was sending its science data to mission controllers from its onboard computer, the downlink was disrupted.

The issue – an inability to directly access the spacecraft memory storing the science data collected during the flyby – was most likely caused by a radiation spike as Juno flew through a radiation-intensive portion of Jupiter’s magnetosphere. Mission controllers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and its mission partners successfully rebooted the computer and, on Dec. 17, put the spacecraft into safe mode, a precautionary status in which only essential systems operate.

As of Dec. 22, steps to recover the flyby data yielded positive results, and the team is now downlinking the science data. There is no indication that the science data through the time of closest approach to Jupiter, or from the spacecraft’s flyby of Jupiter’s moon Io, was adversely affected. The remainder of the science data collected during the flyby is expected to be sent down to Earth over the next week, and the health of the data will be verified at that time. The spacecraft is expected to exit safe mode in about a week’s time. Juno’s next flyby of Jupiter will be on Jan. 22, 2023.

Juno spacecraft recovering its memory after mind-blowing Jupiter flyby, NASA says