NASA will likely use another Starship for the Artemis 4 mission, taking advantage of the Option B in its HLS award to the company it announced earlier this year it would exercise to update the Starship lunar lander for later missions in the "sustainable" phase of Artemis. Credit: SpaceX

HUNTSVILLE, Ala. — NASA has restored plans to include a lunar landing on its Artemis 4 mission to the moon later this decade, months after saying that the mission would instead be devoted to assembly of the lunar Gateway.

In a presentation Oct. 28 at the American Astronautical Society’s Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium here, Mark Kirasich, deputy associate administrator for Artemis Campaign Development at NASA, outlined the series of Artemis missions on the books for NASA through the late 2020s. That included Artemis 4, which he described as the “second time people land on the moon” under Artemis after the Artemis 3 mission.

Kirasich confirmed after the panel that NASA had decided to include a landing on Artemis 4 again. The mission would likely use the “Option B” version of SpaceX’s Starship lander, he said.

NASA announced it would fund Option B at the same time it unveiled the Sustaining Lunar Development (SLD) effort to select a second lunar lander provider for those later missions. Kirasich said it would be unlikely that the lander selected in that program would be ready in time for Artemis 4, and instead would be demonstrated on Artemis 5.

That date, though, will depend on several factors. One is the readiness of the Option B version of the Starship lander. During another panel at the symposium, NASA and SpaceX officials said they were making good progress on the lander but provided few technical details or a schedule.

Rene Ortega, HLS chief engineer at NASA, praised SpaceX for giving the agency access to hardware and test data from the overall Starship launch vehicle development effort. “It’s a big deal,” he said. “It’s one of the practices that I’ve been impressed with.”

The Artemis 4 schedule will also depend on the readiness of the I-Hab module, being developed by Europe and Japan, and the SLS Block 1B itself. That version of SLS, which uses the more powerful Exploration Upper Stage, in turn requires a new mobile launch platform, the Mobile Launcher (ML) 2.

NASA officials, including Administrator Bill Nelson, have been unusually publicly critical of the ML-2 prime contractor, Bechtel, for major cost overruns and schedule delays. “Right now, Mobile Launcher 2 is the critical path to Artemis 4,” said Jeremy Parsons, deputy manager of NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems program, during another conference panel Oct. 27. “It’s something we’re working the schedule very intensively on.”

NASA is currently soliciting proposals for the SLD program, formally known as Appendix P of its Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships, or NextSTEP, effort. NASA issued the call for proposals Sept. 16 with an original deadline of Nov. 15. NASA pushed back the deadline Oct. 21 to Dec. 6 to provide more time for the agency to review requests by companies for use of government facilities.

During a conference panel session Oct. 28, NASA and several companies declined to discuss details about the SLD procurement because it was ongoing, including whether they would submit a proposal and, if so, with whom they were teaming. However, they did discuss work on a separate NextSTEP effort, Appendix N, to support work on sustainable lunar lander technologies. NASA selected five companies in September 2021 for $146 million in studies on key technologies for such landers.

Some of the companies have used the Appendix N awards to continue work on concepts they proposed in the original HLS competition. “Dynetics felt like we had a very sustainable lander approach even in the base period, so we really appreciated the opportunity to further mature that design during Appendix N,” said Andy Crocker, HLS program manager at Dynetics.

He said the company has been working on about 20 different tasks related to risk reduction on its lander design, including the lander’s engine, which uses liquid oxygen and methane propellants. The company performed a static-fire test of that engine a week earlier, he noted.

“I think it helped continue the momentum that we build up under the base period,” said Ben Cichy, senior director of lunar program engineering at Blue Origin, of its Appendix N activities. That included work on cryogenic fluid management for the hydrogen fuel used on its BE-7 engine, as well as precision landing technologies and dust mitigation.

Blue Origin competed for the Option A award ultimately won by SpaceX as part of the so-called “National Team” that included Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, two companies that won separate Appendix N awards. Those companies are examining different approaches to lunar landers.

“Under Appendix N we’ve been given a great opportunity to step back and take a look at everything that has been developed since the Apollo missions,” said John Marzano, Northrop’s HLS program director, “and essentially pick what we think is a series of the best potential characteristics of each of those different concepts.”

He said the company is looking at two parallel efforts for lunar lander engines. One is an internal project leveraging experience dating back to TRW, which developed an engine for the Apollo lunar lander. The other is an engine from Sierra Space. The lander, he said, would use storable propellants rather than cryogenic ones.

Kirk Shireman, vice president, lunar exploration campaign at Lockheed Martin, said his company is examining incorporating nuclear thermal propulsion in its lander architecture, seeing as key to future human exploration of Mars. “Having a high-thrust, high-Isp engine is really key to our future,” he said. Isp, or specific impulse, is a measure of an engine’s efficiency.

He said the company is working on technologies such as cryogenic fluid management, fuel testing and a turbopump design. He said later that the nuclear propulsion system would be used for transit between the Earth and moon.

“We’ve been able to continue our collaboration that we established under the base period of the HLS contract,” he said of the company’s work with NASA. “It’s continuing the great work, the great relationship, that we had through Appendix N so that we can continue it, hopefully, under Appendix P. whenever that comes about.”

"I do everything to make sure that our commitment will be met," European Space Agency chief Josef Aschbacher tells Space.com.

The European Space Agency is supplying the service module for the Orion spacecraft meant for Artemis moon missions. (Image credit: Lockheed Martin)

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — We now know when Europeans will land on the moon alongside NASA astronauts.

Both the Artemis 4 and Artemis 5 moon-landing missions, which are slated to launch in 2028 and 2029, respectively, will feature one European Space Agency astronaut, ESA Director Josef Aschbacher told Space.com. Another ESA astronaut is guaranteed to fly on a future Artemis moon mission, but which one is not decided yet.

"I'm very happy and very proud that NASA is relying on Europe as a partner in providing critical elements" for Artemis missions, Aschbacher said.

He was speaking on July 1 hours after the launch of Euclid, an ESA-led "dark universe" mission that also has NASA participation, and said the agencies seek to have a good dialogue about expectations for all missions. "I do everything to make sure that our commitment will be met," Aschbacher added.

Eight member states of ESA are signatories to the NASA-led Artemis Accords, which aim to set a path for moon exploration and to establish international peaceful norms for space exploration. The addition of India and Ecuador last month brings the number of Artemis Accord signatories to 27.

Europe is also contributing the service module, which supplies electricity and other resources, for NASA's Orion spacecraft, which will carry Artemis astronauts to the moon. And ESA is supplying (in partnership with Japan) a habitat module and a refueling module for NASA's moon-orbiting Gateway space station, a key piece of Artemis infrastructure.

ESA officials previously said that, in exchange, the agency will receive three flight opportunities for European astronauts to launch on Artemis missions, but did not name those flights.

A visualization of the crew segment of the lunar Gateway station. (Image credit: ESA/NASA/ATG Medialab)

ESA also continues to send astronauts to the International Space Station, including Denmark's Andreas Mogensen, who is set to launch on SpaceX's Crew-7 mission on Aug. 15. European astronauts, slated to launch on shorter ISS missions, are also in training with the private company Axiom Space, which uses SpaceX hardware for space missions. Marcus Wandt, from Sweden, will be the first of the group on Ax-3, set to launch in late 2023.

Additionally, discussions are ongoing as to how to bring John McFall — a former Paralympian trauma surgeon selected as an astronaut candidate last year — to the ISS, Aschbacher said. "We have to do a study ... (concerning) whether adaptations need to be made on the interface on the space station" to allow for the flight, he said.

Aschbacher added that the member states of ESA continue to discuss how to get its astronauts to space in the coming years. The agency is debating whether to develop its own spacecraft and infrastructure for missions; discussions will continue at its Space Summit on Nov. 6 and 7, he noted.

Artemis missions are already underway. In November 2022, NASA launched Artemis 1, an uncrewed round-the-moon trip that sent several mannequins and science experiments on a test of Orion and the Space Launch System rocket.

The first crewed mission of the program, Artemis 2, is expected to launch in November 2024 to go around the moon and back. Its quartet of astronauts, named in April 2023, will be the first people to head toward the moon in more than 50 years. Canadian Jeremy Hansen will fly with three NASA astronauts in exchange for Canadarm3, slated to launch to Gateway later in the decade.

NASA then plans to follow up the effort with the Artemis 3 surface mission no earlier than 2025 or 2026, pending readiness of SpaceX's Starship system, which will serve as the mission's lunar lander. The launch dates of Artemis 4 and 5 may therefore adjust depending on when Artemis 3 touches down.

Quelle: Space.com

+++

NASA's new Artemis 'astrovans' arrive for use by moon-bound crews

With the Vehicle Assembly Building in the background, the three specially designed, fully electric crew transportation vehicles for NASA's moon-bound Artemis missions arrived at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Tuesday, July 11, 2023. (NASA/Isaac Watson)

Attention Artemis astronauts, your new rides to the launch pad have arrived

Canoo Technologies on Tuesday (July 11) delivered three specially-designed, fully-electric crew transportation vehicles (CTV) to NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new trio of "astrovans" will enter service as soon as late-2024, when the four astronauts assigned to NASA's Artemis II mission launch on the first crewed mission to fly around the moon in more than 50 years.

"I have no doubt everyone who sees these new vehicles will feel the same sense of pride I have for this next endeavor of crewed Artemis missions," said Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, NASA's Artemis launch director, in a statement.

Canoo based the new NASA crew transports on its LV, or Lifestyle Vehicle, which the company describes as having a "multi-purpose platform to maximize cabin space, utility and productivity on a compact footprint." The three vehicles can carry four astronauts in their Orion crew survival system pressure suits and support personnel (including a suit technician), as well as have the room for specialized equipment for the trip from Kennedy's Neil A. Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building to Complex 39B, where the crew's Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft will be poised for liftoff.

Externally, the new Artemis vehicles appear to be somewhat of a cross between the livery of the Apollo astronaut transfer van with the sleek outline of the shuttle-era Airstream — only with a more modern look accentuated by their street-view windows and panoramic glass roofs.

Many of the design aspects, from the interior and exterior markings to the color of the vehicles to the wheel wells, were chosen by a team that included Blackwell-Thompson and members of NASA's Astronaut Office at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Canoo, which bills itself as an advanced mobility company, was awarded the contract to manufacture the three vehicles in April 2022.

"The collaboration between Canoo and our NASA representatives focused on the crews' safety and comfort on the way to the pad," Blackwell-Thompson said.

For its part, Canoo chairman and CEO Tony Aquila said his company was proud to be a partner with NASA in "one of the world's greatest endeavors."

"The selection of our innovative technologies by NASA to take a diverse team of astronauts to the moon showcases a great commitment to sustainable transportation. We are inspired by NASA's pioneering and trailblazing spirit," said Aquila in a statement.

The Canoo CTVs join a new generation of astrovans that include SpaceX's fleet of Tesla Model X electric cars used to transport Dragon crews and a customized Airstream that will take astronauts flying on Boeing's Starliner to the launch pad.

The Apollo and space shuttle-era vans are now on display at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, in the Apollo/Saturn V Center and Space Shuttle Atlantis exhibit, respectively.

Ahead of being used by Artemis II crew members Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover and Christina Koch of NASA and Jeremy Hansen of the Canadian Space Agency, the new CTV fleet will be used for astronaut training exercises at Kennedy Space Center. The three vehicles will then be used for future missions that will explore the moon's south pole or visit the Gateway in lunar orbit, beginning with Artemis III, which NASA, following the White House's direction, has said will land the first woman and next American on the moon.

Quelle: CS

----

Update: 4.09.2023

.

Lockheed Martin, NASA lining up next Orion spacecraft for Artemis III and IV

Left to right, the Orion crew modules for Artemis III, IV, and II are seen in their Florida production building on June 22. Credit: NASA/Marie Reed.

Orion prime contractor Lockheed Martin has the spacecraft for NASA’s Artemis III and IV lunar landing missions in production alongside the Artemis II vehicle that is going into final assembly at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Simultaneous assembly and test of three Orions is becoming the norm, as the Orion program works towards its goal of delivering one spacecraft every year for eventual, annual Artemis missions.

Following the Artemis II lunar flyby test flight, the Artemis III Orion will be the first to demonstrate full rendezvous and docking operations when it meets up with SpaceX’s Starship lunar lander in cislunar space during the mission. NASA still aspires to fly Artemis III as soon as December 2025, and the space agency continues to stress delivery dates for not just Artemis III, but also for the Artemis IV Orion to follow as close behind as possible.

Artemis III Orion first build under production and operations contract

Lockheed Martin builds the crew module (CM) and crew module adapter (CMA) elements of NASA’s Orion spacecraft in the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout (O&C) Building at KSC; the industrial operations zone (IOZ) in the building is also where final assembly of the CM and CMA with the European Service Module (ESM) occurs. While that final assembly, test, and checkout of the Orion for Artemis II is going on at one end of the IOZ floor, hardware for the next two spacecraft are also being assembled simultaneously.

The Orion program is aiming to have the spacecraft for Artemis III ready for delivery about a year after they turn the Artemis II Orion over to Exploration Ground Systems (EGS) next spring. “[For] Artemis III, there are several things driving [production],” Debbie Korth, Orion Deputy Program Manager for NASA, said during a Aug. 8 media event at KSC.

“The docking system is certainly one of them [and] we have some ECLSS (environmental control and life support system) components coming from one of our subs (subcontractors). A lot of hardware has to get integrated, and then the European Service Module for Artemis III is set to be delivered by the end of this year.”

At a very high level, assembly starts with the structure of the spacecraft. After the primary and secondary structure is assembled, then tubing is welded in a “clean room” area, connecting up plumbing for fluids and propellant. Then wiring harnesses are laid out and connected on the inside and outside of the vehicle, followed by installation of spaceflight equipment, and finally testing and checkout.

As seen on the floor of the IOZ during the early August media event, the CM and CMA for Artemis III have completed structural assembly and are progressing through tube welding as the parts for the tubing are delivered to KSC. Once all the tubing is welded into place, the welds will be proof tested.

“The ideal flow would be [to] have everything here, get it all installed, go in the clean room one time, [and then] do the proof and pressure [test], but it never works out that way,” Korth said. “What they end up doing is as they get components in, they install them, and then they’ll go in and out of the clean room.”

“We do not have all the components in the factory yet for Artemis III, there’s still several dozen that they’re waiting on. Those guys that run the production floor, they keep track of the thousands of components as they’re coming in and resequence things [and] if we’re waiting on something, go do something else.”

“They’re going to install things as they get them and they move the vehicle around between the stations, whether that’s clean room or the other areas,” she explained. “Once components get here, things can go really quickly, I think the Lockheed assembly team they’re very good about rescheduling and resequencing and keeping the vehicle moving.”

The CMA is in a similar situation, it is waiting for a few more tubes to come in for final standalone welding work. “They still have to put some components in it, they still have to build it out, but once the ESM arrives here it’s about three to four months after that when they put them together,” Douglas Lenhardt, NASA Supply Chain Lead for Orion at KSC, said.

The Orion spacecraft for the Artemis III lunar landing mission will be the first to have full rendezvous, proximity operations, and docking (RPOD) capabilities. The Artemis II crew will manually pilot their spacecraft during a proximity operations and handling qualities demonstration on the first day of the mission, but the Artemis III vehicle will have fully automated RPOD software and hardware to link up with SpaceX’s Starship HLS lunar lander in cislunar space.

Korth said that NASA is currently expecting the docking adapter to be delivered to KSC in January. The docking adapter will attach to the front of the crew module and will be jettisoned at the end of the mission. “It’s jettisoned before re-entry, so we don’t bring it back. It’s packed on top of the forward bay cover.”

Lockheed Martin and NASA are still evaluating where in the pre-launch production flow to install the docking adapter. “It is one of the last things that goes on and we’re looking right now at whether or not we can have that installed when we’re in the LASF (Launch Abort System Facility), so kind of playing with the installation sequence to see where that’s most advantageous, but that is one of the last items that goes on.”

After the spacecraft is delivered to EGS, it is moved to the Multi-Payload Processing Facility (MPPF) where commodities like propellant for the spacecraft engines and thrusters and oxygen and water for crew life support are loaded for flight; the spacecraft is then moved to LASF, where the Launch Abort System rocket-and-tower assembly is stacked on top of the crew module. The LASF is the last stop for the spacecraft before it is placed on top of its Space Launch System (SLS) launch vehicle in the Vehicle Assembly Building.

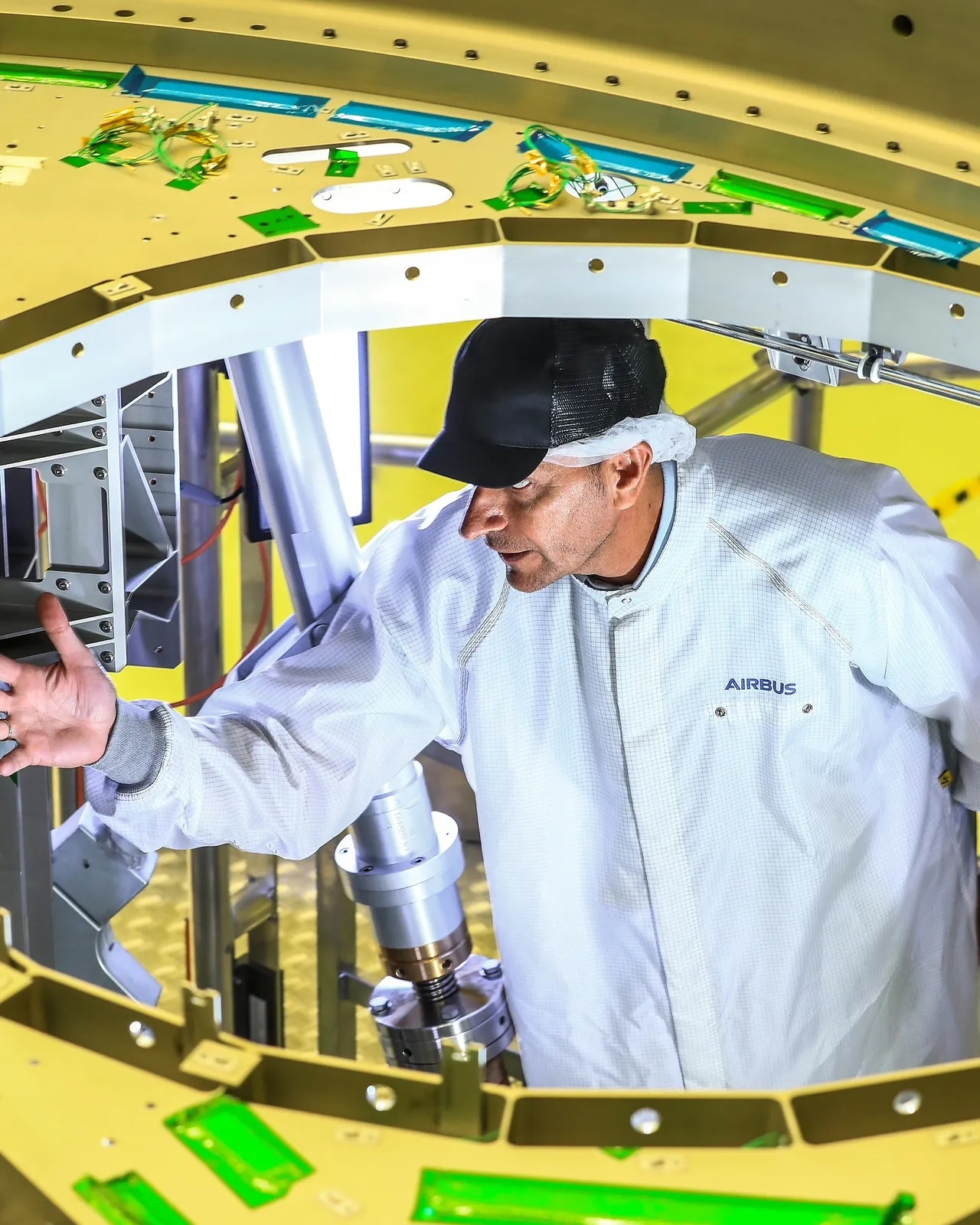

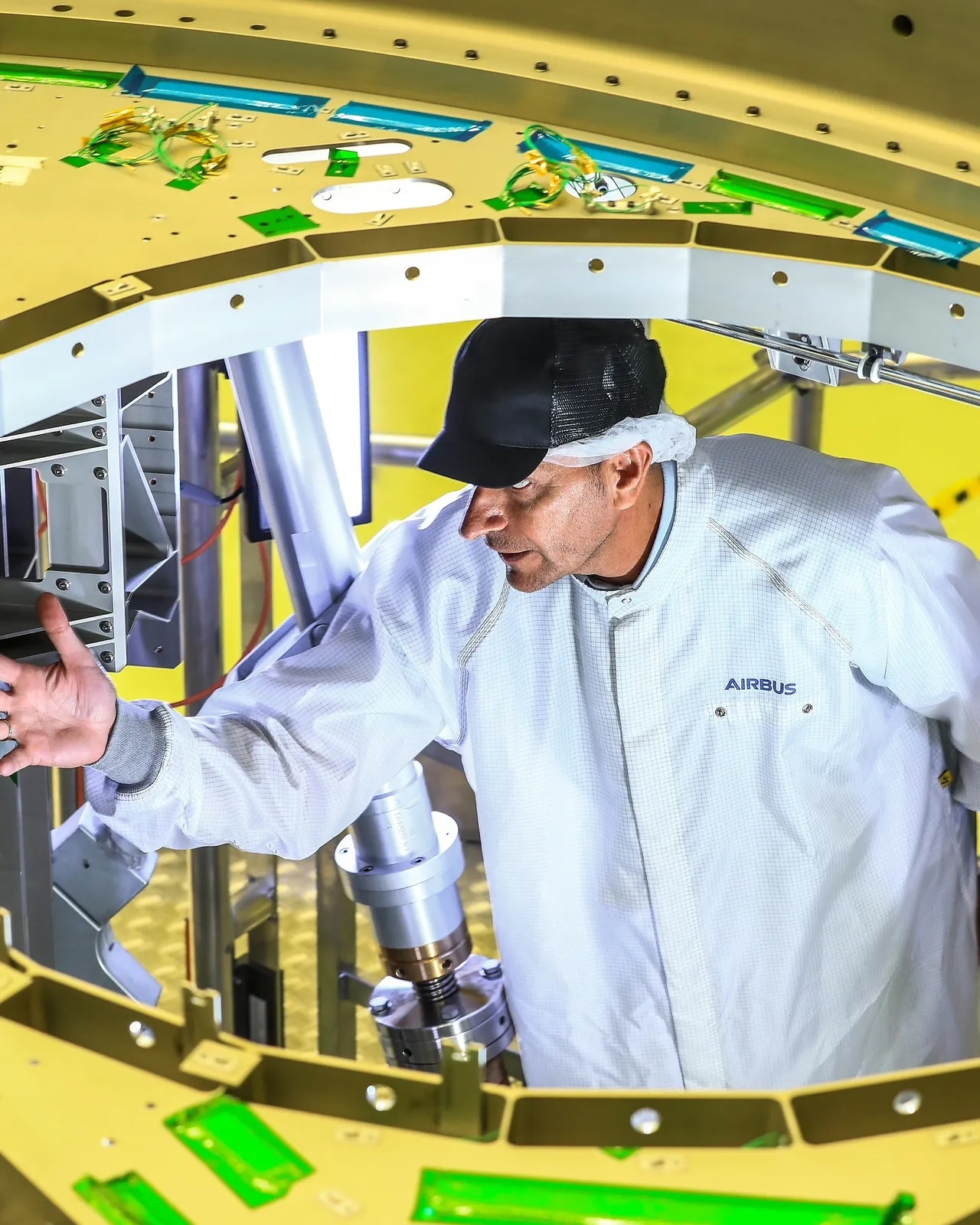

The ESM for Artemis III is a little farther along in its production in Germany. “ESM-3 is currently undergoing final integration steps at our integration facility at Airbus in Bremen, we are finishing the welding for the propulsion part, we are starting to do some testing; at this very moment we are doing the electrical checkouts,” Kai Bergemann, European Service Module Deputy Programme Manager for Airbus, said at the Aug. 8 media event. “We are still on-track for delivery at the end of the year.”

The ESM has the main storage tanks for the multi-week long Orion missions, storing the commodities that are loaded in the MPPF like propellant and oxygen and water. “Those [storage tanks] are all installed, we have all the equipment installed, we just need to finalize some welding on some of the tubes on the propulsion side, but other than that the hardware, the big items, are all integrated,” Bergemann noted.

“Even the large propellant tanks have been integrated some weeks ago, which is a major milestone for us in the progress of that integration, and so now it’s about testing, it’s really about optimizing the test sequence in order to meet the delivery date here.”

As noted, a few months after the ESM arrives in Florida, the CMA and ESM should be ready to mate together to form the service module (SM) for Artemis III. Right now, that would be in the spring 2024 timeframe around the same time that the Artemis II spacecraft is delivered for launch preparations.

Following the mating of the CMA and ESM, the next major milestone for the service module would be initial power-on or IPO, which is the start of the testing and checkout phase for the module. Right now, Orion projects both the crew module and the service module to be ready for their initial power-up in that spring 2024 timeframe.

Each module will go through a series of standalone thermal and acoustic tests; the nozzle for Orion’s main engine would also be installed on the ESM, along with the Spacecraft Adapter that helps join Orion with SLS.

Following standalone testing and checkout, the schedule has the crew and service modules ready to be mated beginning in the fall of 2024. Another round of integrated testing, including a vacuum test in the IOZ, would need to be completed before the solar array wings would be attached and the spacecraft delivered to EGS for Artemis III launch preparations.

Currently, the Orion program’s production goal is to deliver the Artemis III spacecraft to EGS in the spring of 2025, about a year after the Artemis II spacecraft delivery in late April 2024, which would support NASA’s aspirational December 2025 date of launching Orion on an SLS rocket to begin Artemis III and the first mission to land astronauts on the Moon in over 50 years.

Orion looks to block buy of parts to establish delivery cadence, close in on annual goal

The Artemis IV Orion crew module and crew module adapter are also taking shape in the IOZ next to spacecraft it will follow. Structural assembly is still in progress for both elements; the pressure vessel at the center of the crew module was delivered from the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans to KSC in February.

Kaileah Blazek, Mechanical Systems Integration & Test Engineer for Lockheed Martin, said at the Aug.8 media event that the crew module structure had just recently completed its proof pressure test. “We just finished last week,” she said.

“We have about a week worth of test setup and integration, where we actually connect 700 [strain gauge] sensors, and then about a week for the actual test, between performing the test and data review. We do a few runs; we do a max design pressure run and then do the actual full proof pressure run.”

Blazek noted that the maximum pressure test is short; the crew module structure is pressurized to one and a half times its maximum design pressure for less than a minute.

The remainder of the secondary structure will now be installed on the crew module, mostly brackets. “It’s just now getting secondary structure,” Korth said. “I think the guys on the floor call it ‘death by bracket’ because it’s just bracket after bracket after bracket after bracket, it’s somewhere pretty early in the flow.”

Structural assembly of the Artemis IV crew module adapter is also well underway down the IOZ hallway, with longerons and intermediate frames radially attached to the CMA inner ring.

Both Artemis IV structures will proceed into the clean room in 2024 to begin tube welding, and the Orion program team is hoping that the acquisition strategy under the Orion Production and Operations Contract (OPOC) will allow progress to be made towards the long-term production goal of delivering one spacecraft every year for eventual Artemis missions to the Moon every year. At the time the OPOC award was announced in late 2019, the Artemis III, IV, and V vehicles were ordered as a set, so the components for Artemis III that are trailing the production schedule should be delivered with the same parts for Artemis IV and V.

“Our components for Artemis III, IV, and V [are] ordered in lots,” Korth explained. “When Lockheed was put on contract for Artemis III, IV, and V, they [began] buying things in bulk, so while [Artemis] III may be a challenge as we’re waiting for components to come in and have to rework schedules, when we get III, we largely get IV and V as well, because they’re coming in as a set.”

“So, I think these schedule challenges get a little bit easier going forward because we’re getting ahead of getting that hardware into the factory, and once it’s there, there’s a lot more flexibility on the schedule. When you’re waiting on something, you’re at the mercy of the [component schedule].”

n terms of reaching the annual delivery goal in the future, Korth also noted that “there are things like ESMs that need to be delivered on once-a-year centers as well to make that happen,” since the European Service Module contracts are aligned along different builds.

The onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic shortly after the OPOC award and the subsequent supply chain disruption was an additional complication; although the industry and supplier base has recovered significantly, those COVID supply chain effects are still being felt. “I think the supply chain has drastically improved in the last few months, but it is still our biggest challenge,” Korth said.

“In a lot of cases [we are buying] very unique hardware and, you know, we talk about this ‘robust space economy’ that’s being energized and developed, [but] there’s only so many companies that can build environmental control and life systems hardware, or spacesuits or prop systems. Valves is a huge thing; you’re limited by the people who can actually build this kind of hardware and there’s a lot of demand on them right now.”

“It’s getting better, but it’s still a challenge,” she added.

Even with uncertainty about the schedule for Artemis III and other factors that will limit Artemis missions through the 2020s, NASA wants to keep its options open and officials within the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate (ESDMD) have stressed to their programs and contractors to continue working towards long-established “need” dates for deliveries. “The message that we’re trying to take forward is please work to your commitment or your contract dates…until we have to change that with a contract change,” ESDMD Associate Administrator Jim Free said in a briefing to the NASA Advisory Council in May.

“Missions are going to continue to move around and if all we do is move missions around everybody is going to get out of sync. We don’t want to do that anymore; we want to deliver.”

“If we have to put things in storage, we’ll put things in storage,” Free added in May.

“We have a lot of direct interaction with [subcontractors], which I think is really helpful, explaining [our schedules],” Korth noted in August. “Some people think ‘why do you need it so early, [for] Artemis III we don’t know when it’s going to fly?'”

“But we are on a cadence of delivering vehicles and we need to get them done because dragging our team along doesn’t help us if we’re waiting on hardware.”

Similarly, to NASA and Lockheed’s production goal, the European Space Agency and Airbus are working towards delivering ESMs on an annual cadence. “ESM-4 is pretty much one year after ESM-3, so [with ESM-4] we are in the middle of harness integration,” Bergemann said.

“Typically we start with the structure, when we receive the structure we do primary/secondary structure integration, bracket integration, which is followed by harness integration, and the integration of the first propellant tubes, so this is currently ongoing for ESM-4.”

Currently, the Orion program is targeting delivery of the Artemis IV spacecraft to EGS in early 2026. Right now NASA schedules put launch of Artemis IV no earlier than September 2028. In support of that early 2026 delivery date, initial power-on of the crew module would be in late 2024, with the service module IPO following in early 2025.

That would lead to mating of the crew module to the service module in the summer of 2025, followed by final testing through the end of 2025 ahead of delivery to EGS in early 2026.

Orion factoring Artemis I recovery data, experiences into evolving reusability plans

NASA and Lockheed Martin have plans to reuse returning crew modules and crew module hardware extensively beginning with the Artemis III spacecraft; as the program transitions from development into a production and operations phase, those plans are being refined. “Reuse is definitely a work in progress on how it’s going to play out,” Korth said.

“That plan is evolving and a lot of it has to do with [what] we learned off Artemis I when we got the spacecraft back, [such as] how long it takes to decontaminate and get that module itself to a point where you could actually install new components on it, so ripping everything off that you can’t reuse.”

She gave an example: “Things like you splashdown in the ocean and saltwater. We found on Artemis 1 when they took off the [backshell] panels you see salt crystals everywhere, so we’ve got to start talking about corrosion resistance and what kind of coatings are we going to put on things so we can reuse them.”

“You’re just learning as you go along, but [reuse is] definitely a priority for the program and I think it’s the right answer, it’s just doing the work to enable all that to happen.”

n addition to the electronics that were removed from the Artemis I spacecraft as soon as possible to be refurbished for installation on the Artemis II spacecraft early in 2023, Orion is looking at the condition of the spacecraft and the other equipment that came back from the program’s first mission to the Moon and back, and how long it will take to refurbish them and turn them around for a next flight.

“We learned more about the timeline to do that, and then we’ve learned more about when you do take a component out that requires a [subcontractor] to rework,” Korth explained. “Lockheed has started working those contracts with those subs and what we may have estimated it being six or eight weeks could be six or eight months.”

“And so you’re looking at maybe I can’t use that item from [Artemis] III to [Artemis] VI, I need to use it from III to VII, so then what do I do on [Artemis] VI? The reuse plan is definitely evolving as we learn more from our suppliers what they can do [and] learn more about what we can do in terms of processing the spacecraft here at Kennedy, [with] the biggest thing being cleaning out [propellant].”

“Prop is a big deal and there’s only a couple of facilities you can do that in, and one of them is not the O&C right now,” Korth added. “If we want to get back into the factory we’ve got to work that.”

The naming conventions for reuse are also evolving with the plans. “We got rid of the monikers of ‘light and heavy’ and we call [it] ‘component and module’ [reuse],” Korth noted.

Quelle: NSF

----

Update: 12.11.2025

.

Europe Readies Artemis IV’s Orion Module For U.S. Trip

Credit: Airbus

Airbus says it is shipping the fourth European Service Module (ESM-4) to the U.S. to support a future Artemis IV mission despite uncertainty over that endeavor.

ESM-4 has completed integration at Airbus’s facility in Bremen, Germany, and is now being prepared to be shipped to Kennedy Space Center, Florida, to be integrated with an Orion Crew Module, Airbus and Thales Alenia Space, a key partner on the program, said Nov. 10.

“ESM-4 will play a key role as the Artemis IV mission is due to deliver the International Habitation Module (Lunar I-Hab) of the Lunar Gateway space station,” Daniel Neuenschwander, ESA’s director of Human and Robotic Exploration, said in a statement.

But when the mission may take place, if at all, is unclear. The Trump administration’s 2026 budget request calls for the Artemis program and Orion to end after the Artemis III mission, due in 2027, that aims to return humans to the lunar surface. Congress could restore funding for missions beyond Artemis III, and both the House and Senate have suggested they would stick with the program through at least Artemis V.

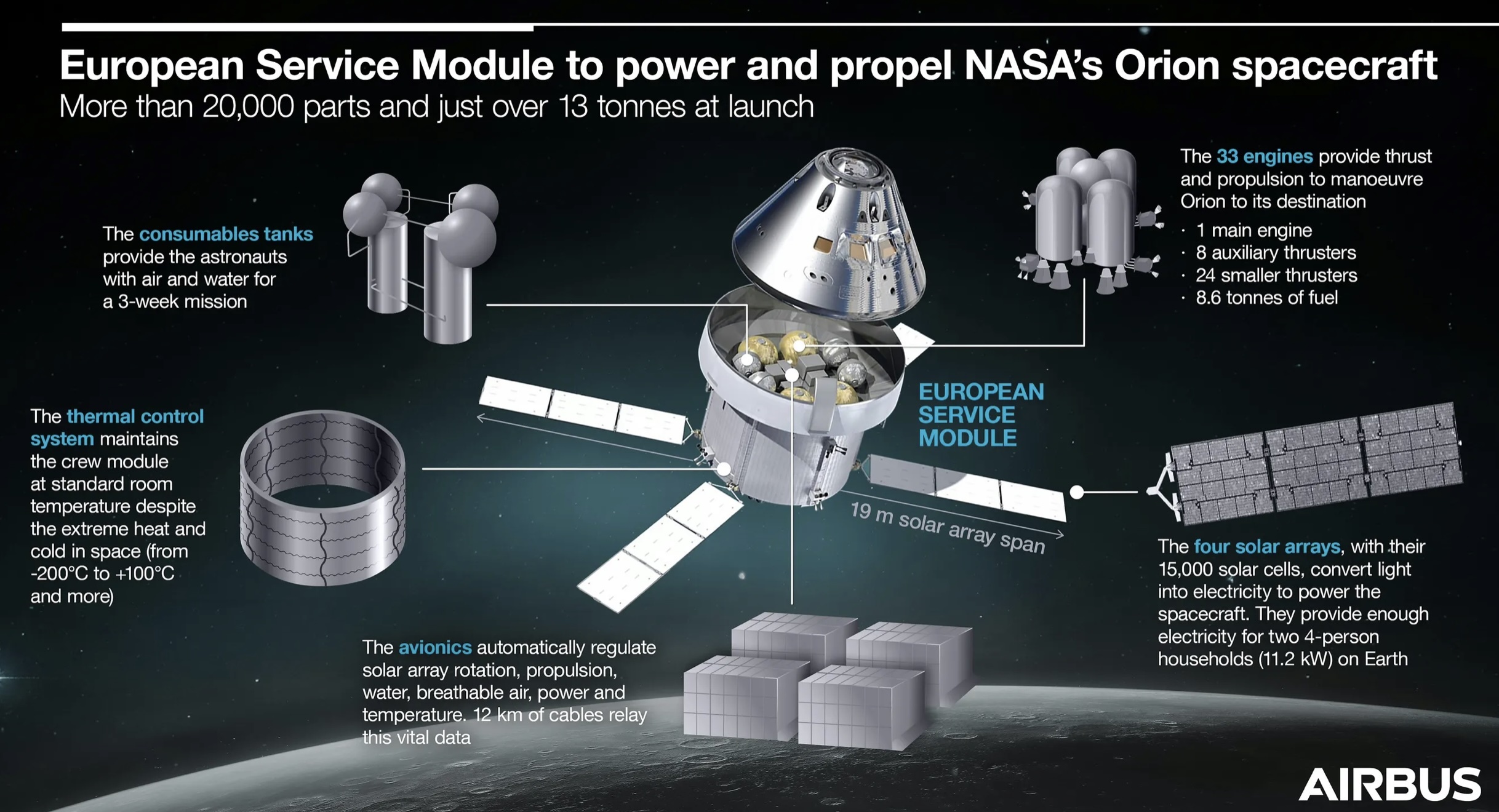

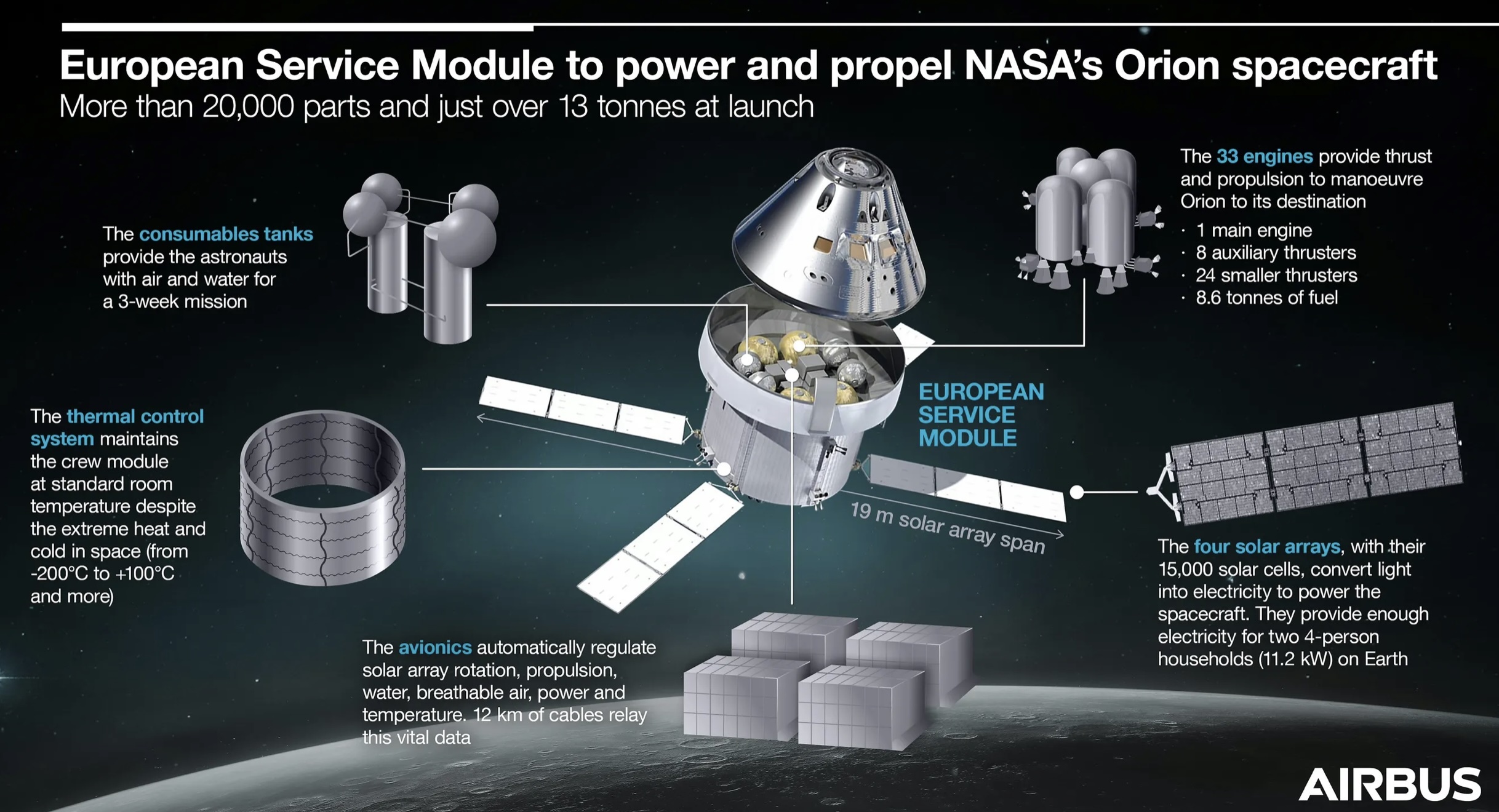

The ESM system provides key life-support elements for the Orion crew capsule. Thales Alenia Space provides the thermal control system.

Quelle: AVIATION WEEK

+++

Building of ESM-4 to ESM-6 at Airbus Bremen cleanroom

The fourth ESM will propel the Orion spacecraft of the Artemis IV mission into the correct orbit to dock with the Gateway space station and enable the astronauts to enter their new living space. This mission will also transport the main habitation module of the lunar space station.

At the Bremen site we have adjusted our cleanroom facilities with the ambition to deliver one ESM per year - a production rate unheard of for human-rated spacecraft in Europe.

Bremen, Germany, – The fourth European Service Module (ESM-4) is ready to leave Airbus’ facilities in Bremen, Germany, and be shipped to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, USA. On arrival it will be tested and integrated with the Orion Crew Module ready for the next stage of NASA’s Artemis programme.

Built by Airbus under contract to the European Space Agency (ESA), ESM-4 will be a vital part of the Artemis IV mission which envisages astronauts going to live and work in humanity’s first lunar space station, Gateway, which will enable new opportunities for science and preparation for human missions to Mars.

“Delivering the fourth ESM takes us one step closer to a new space era with a lunar space station and increased opportunities for deep space scientific research. Europe’s role, through ESA, is crucial in this pioneering NASA-led programme,” said Ralf Zimmermann, Head of Space Exploration at Airbus.

“ESM-4 will play a key role as the Artemis IV mission is due to deliver the International Habitation Module (Lunar I-Hab) of the Lunar Gateway space station. This state-of-the-art hardware, developed by Airbus Defence and Space and its subcontractors across Europe, demonstrates our ability to contribute to major international partnerships,” said Daniel Neuenschwander, Director of Human and Robotic Exploration at ESA.

The ESM modules provide engines, power, thermal control, and supply astronauts with water and oxygen. The ESM is installed underneath the crew module and together they form the Orion spacecraft. Thales Alenia Space Italia provides the thermal control system to keep the Orion crew modules between 18 and 24°C by radiating excess heat out of the ship but also keeping the cold at bay.

The four solar arrays on Orion generate 11.2 kW of electricity, enough to power two four-person households on Earth. Only about 10% of the power is needed for the ESM, with the remaining 90% going to the batteries and equipment in the crew module. The Artemis I mission showed the solar panels were able to produce a little more power than expected and this additional energy will be of use as the Artemis programme evolves.

The energy stored in the batteries of the Crew Module is key as it ensures that the Orion spacecraft has power even when the Sun is obscured. The batteries also provide power for a safe return when the ESM separates from the crew module at the end of the mission.

To enable astronauts to concentrate on the most important tasks, the electronics onboard the ESM, controlled by the Crew Module, provide a very high level of autonomy, such as temperature regulation and solar wing rotation to track the Sun.

Orion has 33 engines onboard the ESM to provide thrust and manoeuvring capabilities. The main engine, a repurposed Space Shuttle orbital manoeuvring system engine (OMS-E) provided by NASA, generates 26.5 kilonewtons of thrust. This provides enough force to escape Earth’s gravitational field and perform the translunar injection burn, and to get into the Moon’s orbit. Eight auxiliary thrusters act as back-ups to the OMS-E and for orbital corrections. There are also 24 smaller engines for attitude control in space, enabling the spacecraft to rotate or change its angle during docking manoeuvres.

Quelle: AIRBUS

----

Update: 7.12.2025

.

NASA Selects 2 Instruments for Artemis IV Lunar Surface Science

NASA has selected two science instruments designed for astronauts to deploy on the surface of the Moon during the Artemis IV mission to the lunar south polar region. The instruments will improve our knowledge of the lunar environment to support NASA’s further exploration of the Moon and beyond to Mars.

“The Apollo Era taught us that the further humanity is from Earth, the more dependent we are on science to protect and sustain human life on other planets,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator, Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “By deploying these two science instruments on the lunar surface, our proving ground, NASA is leading the world in the creation of humanity’s interplanetary survival guide to ensure the health and safety of our spacecraft and human explorers as we begin our epic journey back to the Moon and onward to Mars.”

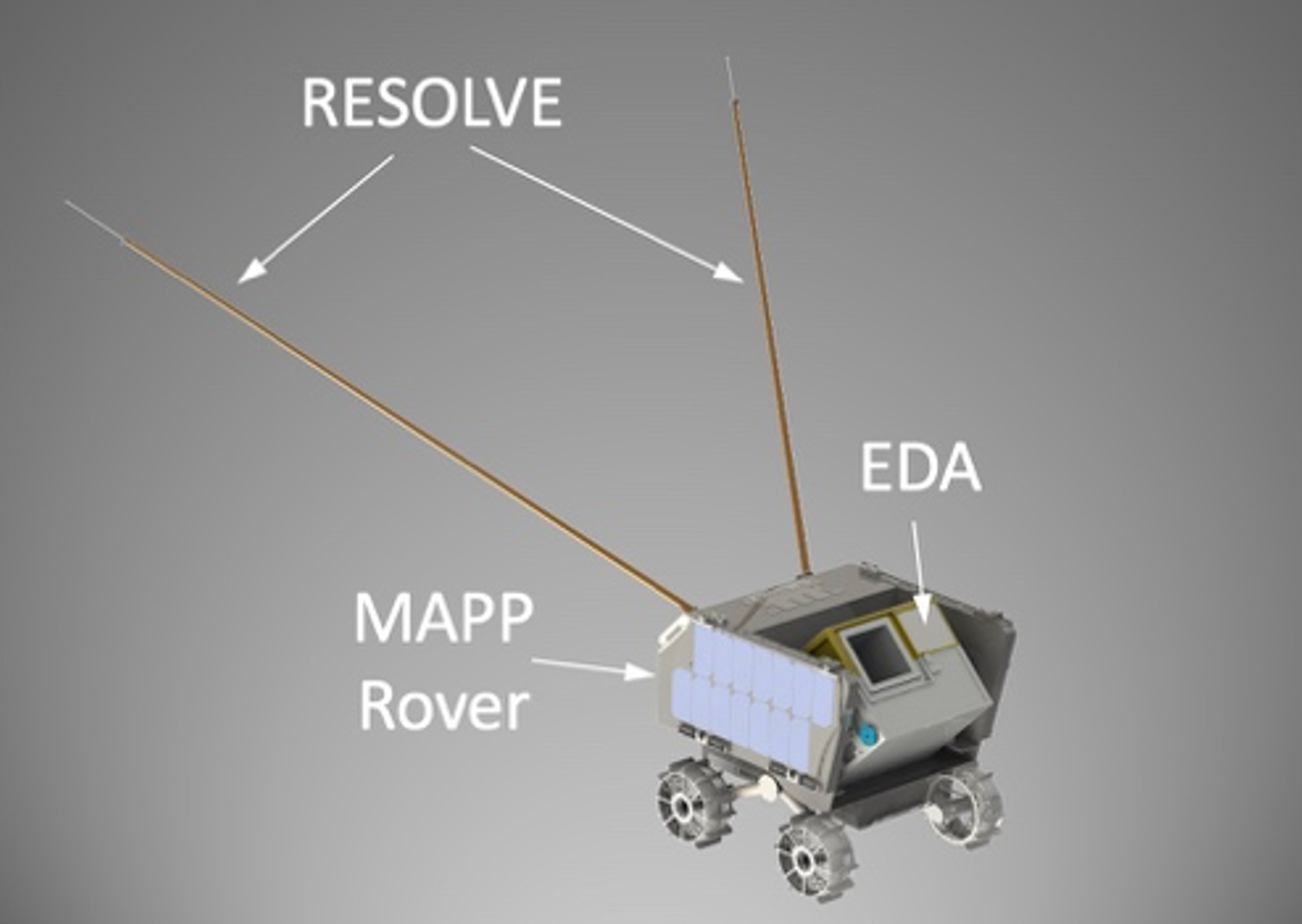

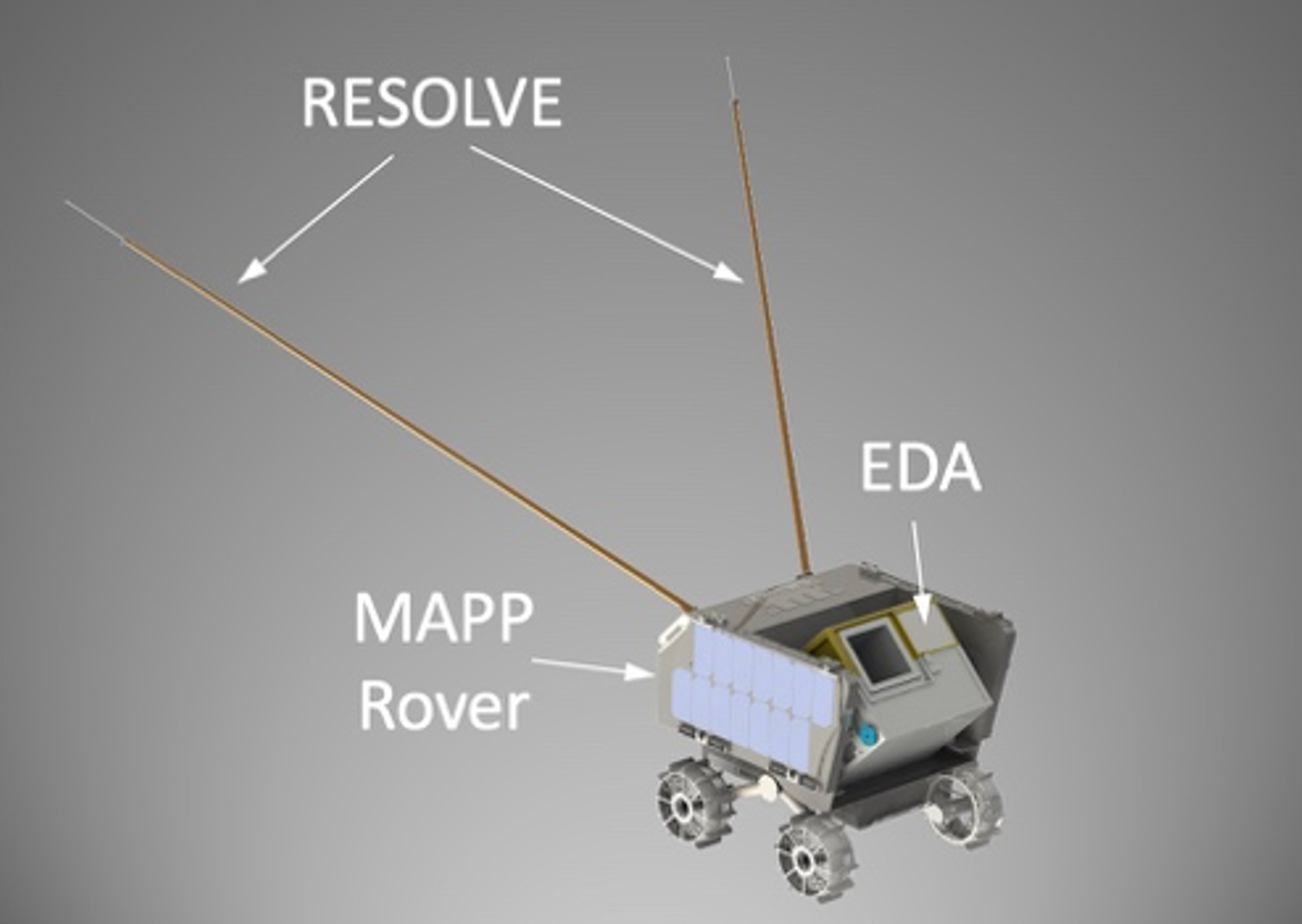

After his voyage to the Moon’s surface during Apollo 17, astronaut Gene Cernan acknowledged the challenge that lunar dust presents to long-term lunar exploration. Moon dust sticks to everything it touches and is very abrasive. The knowledge gained from the DUSTER (DUst and plaSma environmenT survEyoR) investigation will help mitigate hazards to human health and exploration. Consisting of a set of instruments mounted on a small autonomous rover, DUSTER will characterize dust and plasma around the landing site. These measurements will advance understanding of the Moon’s natural dust and plasma environment and how that environment responds to the human presence, including any disturbance during crew exploration activities and lander liftoff. The DUSTER instrument suite is led by Xu Wang of the University of Colorado Boulder. The contract is for $24.8 million over a period of three years.

A model of the DUSTER instrument suite consisting of the Electrostatic Dust Analyzer (EDA)—which will measure the charge, velocity, size, and flux of dust particles lofted from the lunar surface—and Relaxation SOunder and differentiaL VoltagE (RESOLVE)—which will characterize the average electron density above the lunar surface using plasma sounding. Both instruments will be housed on a Mobile Autonomous Prospecting Platform (MAPP) rover, which will be supplied by Lunar Outpost, a company based in Golden, Colorado, that develops and operates robotic systems for space exploration.

LASP/CU Boulder/Lunar Outpost

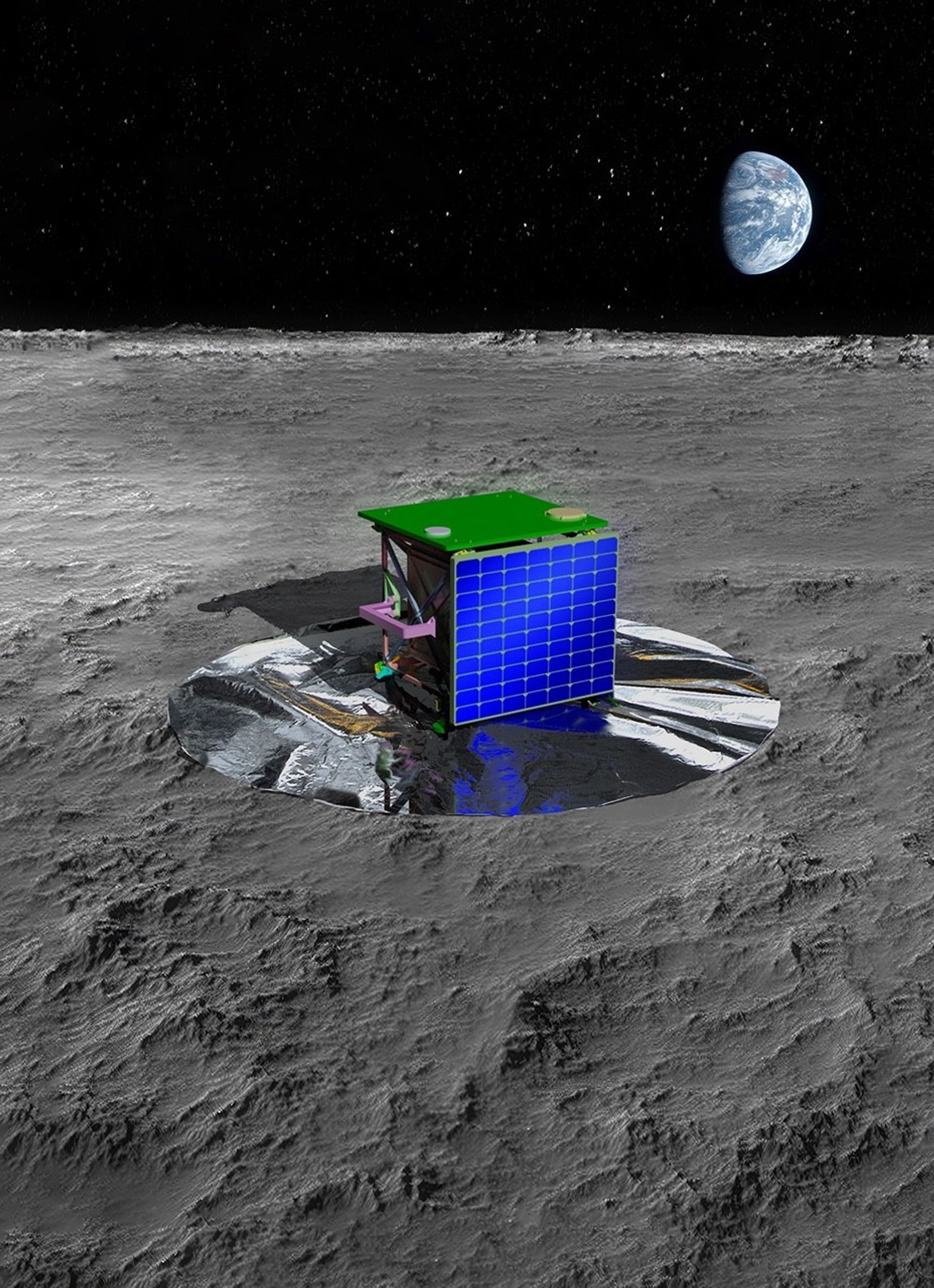

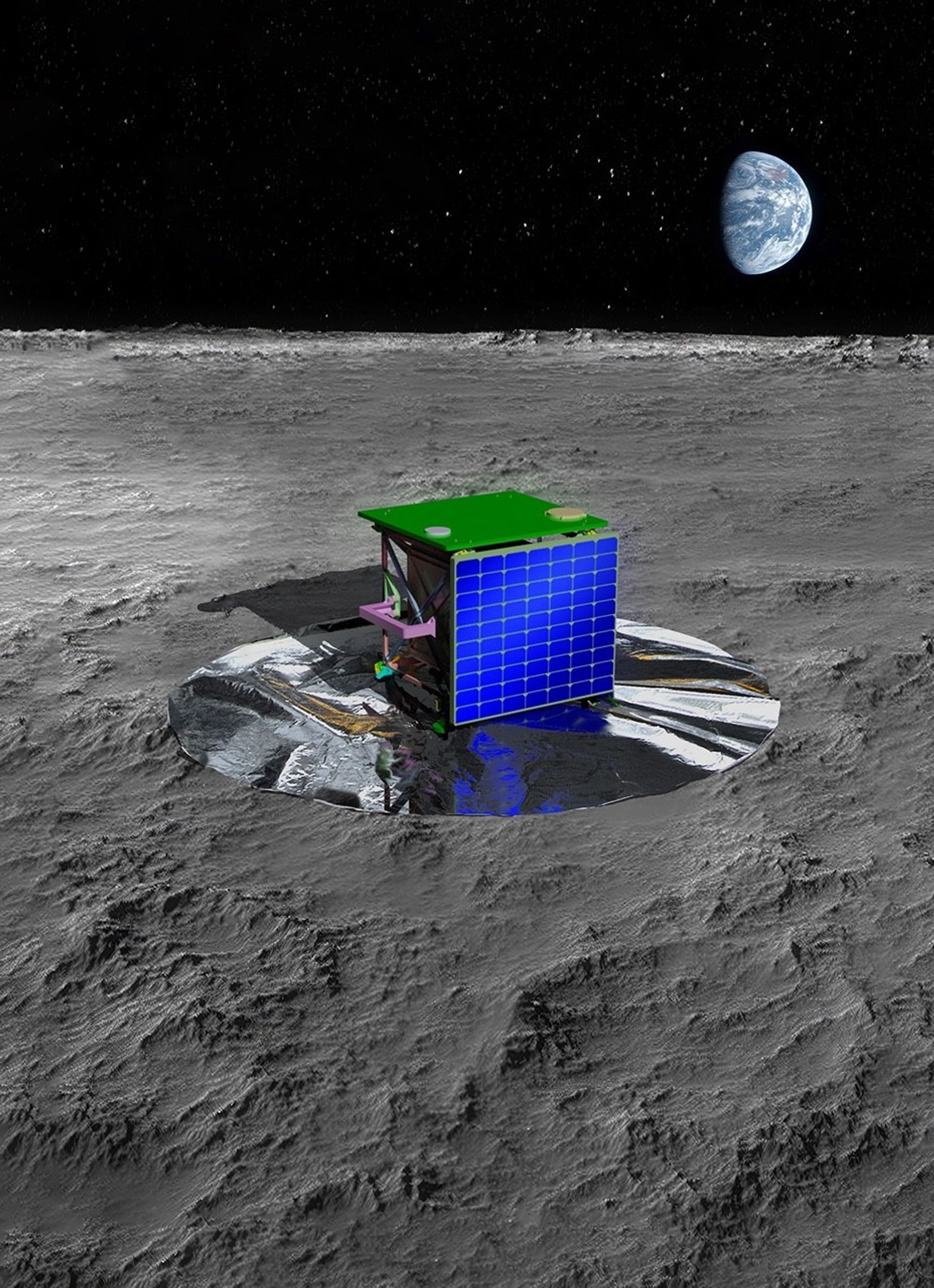

Data from the SPSS (South Pole Seismic Station) will enable scientists to characterize the lunar interior structure to better understand the geologic processes that affect planetary bodies. The seismometer will help determine the current rate at which the Moon is struck by meteorite impacts, monitor the real-time seismic environment and how it can affect operations for astronauts, and determine properties of the Moon’s deep interior. The crew will additionally perform an active-source experiment using a “thumper” that creates seismic energy to survey the shallow structure around the landing site. The SPSS instrument is led by Mark Panning of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. The award is for $25 million over a period of three years.

An artist’s concept of SPSS (South Pole Seismic Station) to be deployed by astronauts on the lunar surface.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

"These two scientific investigations will be emplaced by human explorers on the Moon to achieve science goals that have been identified as strategically important by both NASA and the larger scientific community", said Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration, Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters. “We are excited to integrate these instrument teams into the Artemis IV Science Team.”

The two payloads were selected for further development to fly on Artemis IV; however, final manifesting decisions about the mission will be determined at a later date.

Through Artemis, NASA will address high priority science questions, focusing on those that are best accomplished by on-site human explorers on and around the Moon and by using the unique attributes of the lunar environment, aided by robotic surface and orbiting systems. The Artemis missions will send astronauts to explore the Moon for scientific discovery, economic benefits, and build the foundation for the first crewed missions to Mars.

Quelle: NASA