24.05.2022

NASA unveils Artemis 1 moon mission launch windows through mid-2023

NASA's first Space Launch System, the Artemis 1 moon rocket, stands atop Launch Pad 39B during sunrise in this photo taken March 23, 2022. (Image credit: NASA/Ben Smegelsky)

NASA's first Space Launch System, the Artemis 1 moon rocket, stands atop Launch Pad 39B during sunrise in this photo taken March 23, 2022. (Image credit: NASA/Ben Smegelsky)

While Artemis 1's rocket and spacecraft are back in the shop for a few more weeks, NASA has released all the launch opportunities the mission has in 2022.

The Artemis 1 moon rocket could lift off for a round-the-moon mission as soon as July 26, although the agency has plotted out dozens of launch possibilitiesbetween then and December 22, with even more launch options to the moon through June 2023.

These dates are assuming the Space Launch System passes its wet "dress rehearsal" that simulates fueling operations, and overcomes the problems that required a rollback from the launch pad to the Kennedy Space Center's Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on April 26.

Engineers are working to address the hydrogen leak in the umbilical lines and found a damaged O-ring seal that underwent replacement, NASA said in a blog post May 13.

Per NASA, below is the full list of opportunities under consideration on this pathfinder mission to get ready for crewed missions to the moon later in the 2020s. All dates following the July 26 to Aug. 10 window are based on preliminary analysis of the factors needed to get the launch moving to the moon and back, and are subject to change. You can also download NASA's full Artemis 1 launch window calendar as a PDF.

Here's a look at the launch windows remaining in 2022.

- July 26 – Aug. 10: 13 launch opportunities, excluding Aug. 1, 2, and 6;

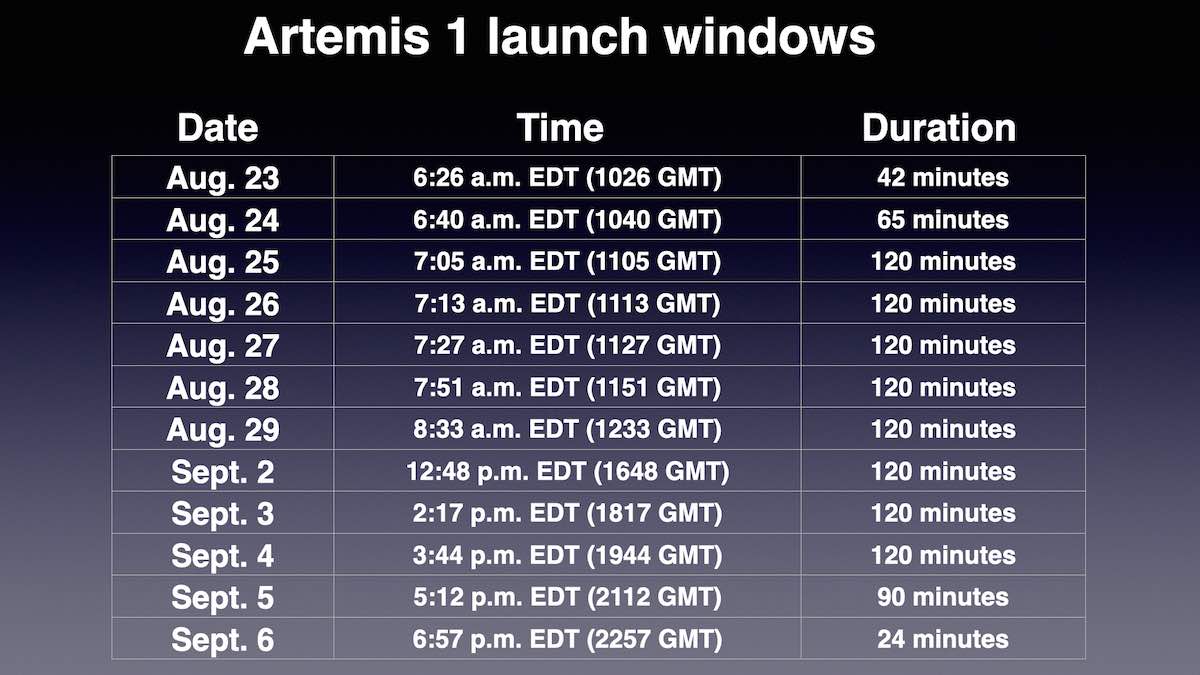

- Aug. 23 – Sept. 6: 12 launch opportunities, excluding Aug. 30, 31, and Sept. 1;

- Sept. 20 – Oct. 4: 14 launch opportunities, excluding Sept. 29;

- Oct. 17 – Oct. 31:11 launch opportunities, excluding Oct. 24, 25, 26, and 28;

- Nov. 12 – Nov. 27: 12 launch opportunities, excluding Nov. 20, 21, and 26;

- Dec. 9 – Dec. 23: 11 launch opportunities, excluding Dec. 10, 14, 18, and 23;

And here are the launch windows for Artemis flights in 2023.

- Jan. 7-20: 10 launch opportunities, excluding Jan. 10, 12, 13 and 14;

- Feb. 3-17: 14 launch opportunities, excluding Feb. 10;

- March: 19 launch opportunities between March 1-17 and March 29-31, excluding March 11 and March 18-28;

- April: 14 launch opportunities between April 1-13 and April 26-30, excluding April 2, 3, 7, 9 and 14-25;

- May: 14 launch opportunities between May 1-10 and May 26-31, excluding May 8 and May 11-25;

- June: 13 launch opportunities from June 1-6, on June 20 and from June 24-30, excluding June 5, 7-19 and 21-23;

NASA's Artemis 1 mission, stacked at the launch pad as seen from space by the Pléiades Neo satellite, operated by the European aerospace company Airbus. (Image credit: Airbus)

NASA's Artemis 1 mission, stacked at the launch pad as seen from space by the Pléiades Neo satellite, operated by the European aerospace company Airbus. (Image credit: Airbus)

"In addition to the launch opportunities based on orbital mechanics and performance requirements, there also is an operational constraint driven by infrastructure at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida," NASA noted of the launch dates when they were released on May 16.

"Because of their size, the sphere-shaped tanks used to store cryogenic propellant at the launch pad can only supply a limited number of launch attempts depending on the type of propellant," the agency added. Essentially, any week only has three maximum launch attempts available due to the core stage tanking process.

Because liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen are loaded into the core stage and upper stage on launch day, engineers must wait 48 hours to make a second launch attempt. A third attempt must wait an additional 72 hours, "due to the need to resupply the cryogenic storage sphere with more propellant from nearby sources," NASA said.

NASA outlined four main constraints when it comes to planning launch dates, aside from the fueling operations.

The first is to make sure that the moon is within reach of the massive SLS rocket's upper stage, which will perform a trans-lunar injection to move the Orion spacecraft towards the moon. Orion will then fly in a distant retrograde orbit. (Retrograde means that it will orbit the moon in the opposite direction to that in which the moon spins.)

The second constraint is making sure Orion's solar panels are not out of the sun for more than 90 minutes, so that the spacecraft has enough electricity to operate and to stay at a healthy temperature range. Orbital dynamicists must take into account the positions of the Earth, moon and sun (which pull upon the spacecraft with their gravity) as well as the "state of charge" on the battery to plot this out properly.  NASA is sending a manikin on its Artemis 1 mission to gather data about how astronauts will experience the flight around the moon. It is called "Commander Moonikin Campos" after Arturo Campos, who assisted with bringing Apollo 13 safely back to Earth in 1970. (Image credit: NASA) The third constraint is making sure Orion can perform a "skip entry" when returning to Earth, which is only allowable with certain launch dates. Orion will use the upper part of Earth's atmosphere, along with its inherent lift, to slow down a bit while skipping deliberately out of the atmosphere temporarily. Then it will re-enter for final descent and splashdown.

NASA is sending a manikin on its Artemis 1 mission to gather data about how astronauts will experience the flight around the moon. It is called "Commander Moonikin Campos" after Arturo Campos, who assisted with bringing Apollo 13 safely back to Earth in 1970. (Image credit: NASA) The third constraint is making sure Orion can perform a "skip entry" when returning to Earth, which is only allowable with certain launch dates. Orion will use the upper part of Earth's atmosphere, along with its inherent lift, to slow down a bit while skipping deliberately out of the atmosphere temporarily. Then it will re-enter for final descent and splashdown.

"The technique allows engineers to pinpoint Orion's splashdown location and on future missions, will help lower the [gravity] loads astronauts inside the spacecraft will experience, and maintain the spacecraft's structural loads within design limits," NASA stated.

Lastly, Orion must launch at a time to allow for daylight recovery conditions after splashdown to assist in recovery operations. This will be especially crucial when people are on board.

The launching date of the mission will also determine how long Orion is in space. The mission will either be between 26 and 28 days long, or between 38 and 42 days.

"The mission duration is varied by performing either a half lap or 1.5 laps around the Moon in the distant retrograde orbit, before returning to Earth," NASA said.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 31.05.2022

.

Next SLS countdown rehearsal scheduled for June 19

WASHINGTON — NASA has tentatively scheduled the next attempt to fuel the Space Launch System and go through a practice countdown for June 19, two weeks after the vehicle returns to the launch pad.

At a May 27 briefing, NASA officials said they were wrapping up work on the rocket in the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center. The rocket returned to the VAB a month ago after three attempts to complete a wet dress rehearsal (WDR) at Launch Complex 39B in the first half of April.

Cliff Lanham, senior vehicle operations manager for NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems program, said a “call to stations” for the rollout is scheduled for the evening of June 5. The rollout will start at around midnight Eastern June 6. That is about six hours later than the first rollout in March, which he said is intended to make it less likely thunderstorms will interfere with the rollout.

That would set NASA up to make its fourth WDR attempt no earlier than June 19, depending on weather and any potential range constraints, he said.

NASA hopes this fourth attempt will be successful, filling both the core stage and the upper stage with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants and going through a countdown that stops just before the core stage’s engines would ignite. However, Tom Whitmeyer, deputy associate administrator for common exploration systems development, said the agency will “add a little schedule this time around to make sure if we have to do more than one wet dress rehearsal attempt, we’re ready to support that.”

Whitmeyer and Lanham said they felt confident workers had fixed the problems experienced during the April WDR attempts, including replacing a helium check valve in the upper stage and tightening flange bolts on an umbilical believed to be the source of a hydrogen leak. “All the things we’ve seen so far have been very positive in terms of the actual performance of the hardware,” Whitmeyer said.

While the SLS was back in the VAB, Air Liquide, the contractor that runs the nitrogen gas distribution system at the center, completed an upgrade to increase the amount of gas available for SLS operations, an issue that cropped up during the earlier WDR attempts. That upgraded system completed a 34-hour test that exceeded the requirements for SLS, said John Blevins, NASA SLS chief engineer.

NASA also used the vehicle’s time to perform some work that was scheduled for after the WDR. That included opening up the Orion spacecraft and installing some of the payloads it will carry on the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission and removing instrumentation on the SLS used to measure the loads on it during the first rollout.

Thar work, Lanham said, “will really help us from the standpoint of the volume of work” that will need to be done after WDR to get the vehicle ready for launch. He didn’t give an estimate of how much time NASA saved by doing that work early, but noted doing it now avoided delays from “nonconformances” technicians encountered.

“It allows us to lessen the demand on our resources when we do get back in the VAB and, I feel, lessen the risk on our overall schedule for rolling back out for launch,” he said.

Agency officials have previously stated they will wait until after the WDR is complete to set a formal launch date for Artemis 1, but Whitmeyer reiterated recent statements by officials, including NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, that NASA hopes to launch the mission in August. NASA has published launch windows for the mission of July 26 through Aug. 10, excluding Aug. 1, 2 and 6, as well as Aug. 23 through Sept. 6, excluding Aug. 30, 31 and Sept. 1.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 7.06.2022

.

NASA’s SLS moon rocket returning to launch pad today for more testing

NASA’s first Space Launch System moon rocket rolled out to its launch pad early Monday at the Kennedy Space Center for another attempt later this month to fully load it with super-cold propellants, the culmination of a countdown rehearsal officials aim to complete before moving forward with launch later this summer.

The towering 322-foot-tall (98-meter) rocket began the journey at 12:15 a.m. EDT (0415 GMT) Monday with first motion out of High Bay 3 inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, the iconic hangar at Kennedy originally built to stack and service Saturn 5 moon rockets during the Apollo program.

The SLS moon rocket and its mobile launch platform rode to pad 39B on a diesel-powered crawler-transporter. The 4.2-mile (6.8-kilometer) journey took about 10-and-a-half hours to complete. The lowering of the moon rocket’s platform onto support posts at the launch pad marked the official conclusion of the journey at 10:47 a.m. EDT (1447 GMT), according to a NASA spokesperson.

The full stack weighed about 21.4 million pounds for rollout.

The huge rocket is the largest ever built by NASA, and is the centerpiece of the agency’s Artemis moon program, which aims to return astronauts to the lunar surface later this decade. NASA is preparing the first SLS moon rocket for the Artemis 1 test flight, a demo mission to send an unpiloted Orion crew capsule around the moon and back to Earth on a shakedown cruise before it flies with people.

In the run-up to the Artemis 1 launch, NASA teams at Kennedy have stacked the SLS moon rocket and rolled the launcher to pad 39B for the first time March 18 in advance of a “wet dress rehearsal” to test out countdown procedures and fully load the rocket with more than 750,000 gallons of super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants.

But a series of technical snags prevented NASA’s launch team from completing the countdown rehearsal in April.

A problem with ground equipment at the launch pad delayed the test a day from April 3, then encountered issues with the supply of nitrogen gas to the launch pad. The nitrogen is used to purge compartments inside the SLS moon rocket.

A fueling attempt April 4 was cut short by concerns about the temperature of liquid oxygen flowing into the rocket’s core stage, then engineers discovered problem with a helium valve on the SLS upper stage.

The helium valve issue prevented the launch team from pumping propellants into the upper stage on the next fueling attempt. But NASA tried again April 14 to load cryogenic propellants into the core stage, but ran into more problems with the nitrogen supply. After temporarily overcoming the nitrogen issue, the launch team detected indications of a hydrogen leak near an umbilical connection at the bottom of the core stage.

NASA officials then decided to return the rocket to the VAB for repairs.

The Artemis 1 launcher rolled back to the hangar April 26, and technicians inside the high bay tightened seals on the umbilical connection in hopes of fixing the hydrogen leak. Workers also swapped out the balky helium valve on the upper stage, which failed due to rubber debris stuck in the mechanism. NASA said teams inside the VAB also worked to ensure no more debris would pose a problem for the new valve.

Meanwhile, upgrades at an off-site nitrogen gas plant near the Kennedy Space Center were completed to expand the system’s capacity for the SLS moon rocket. The nitrogen facility is operated by Air Liquide.

With the troubleshooting behind them, NASA teams have returned the Artemis 1 moon rocket to pad 39B for another countdown dress rehearsal, or WDR, later this month. If all goes according to plan, the next attempt to fully load the SLS moon rocket with propellant is scheduled for June 19.

Before then, ground teams at the space center will ready the rocket for the practice countdown. Those tasks will include loading the steering, or gimbaling, mechanism on the rocket’s two solid-fueled boosters with hydrazine fuel, which feeds hydraulic power units in the booster thrust vector control system.

The countdown test will end with a cutoff just inside T-minus 10 seconds, before ignition of the rocket’s four core stage engines.

If the launch team is able to accomplish the WDR, NASA will roll the Space Launch System back to the assembly building for final closeouts and testing. NASA will haul the rocket to pad 39B again for the real launch campaign, currently scheduled for no earlier than August.

The agency is not setting an official target launch date until successfully completing the WDR.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 17.06.2022

.

WASHINGTON — NASA managers say they have completed testing of the Space Launch System after a recent countdown rehearsal and are ready to move into preparations for a launch as soon as late August.

In a briefing June 24, agency officials declared the test campaign for the SLS complete after a fourth wet dress rehearsal (WDR) of the vehicle at Launch Complex 39B four days earlier. That test stopped at T-29 seconds, about 20 seconds early, because of a leak in a hydrogen bleed line.

Phil Weber, senior technical integration manager for NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems program, said at the briefing that despite the early cutoff, only 13 of 128 planned “commanded functions” were not successfully completed during the terminal phase of the countdown. Most of those 13, he said, had previously been tested, such as retracting umbilicals.

Of the remainder, NASA plans to perform one additional test at the pad of hydraulic power units used to gimble the nozzles of the vehicle’s solid rocket boosters. “The component is extremely robust, but the function is extremely important, so we just want to spin that up,” said John Blevins, SLS chief engineer.

The other functions not tested involved de-energizing ground power supplies before disconnecting umbilicals, a step intended to avoid igniting any leaks of hydrogen. Weber said he was not worried about not testing that since the risk of ignition requires multiple failures. “That was really the only set we didn’t get validated,” he said.

The decision to conclude the WDR campaign has the concurrence of agency leadership, including Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development. Free said in a June 15 briefing that he believed NASA needed “to understand what every situation is and run it to ground before we would press to commit to launch.”

“We did go through that with Jim and he did give is the go-ahead to proceed,” said Tom Whitmeyer, deputy associate administrator for common exploration systems development.

NASA plans to roll the mobile launch platform carrying SLS back to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) early July 1, weather permitting. Once back in the VAB, crews will spend several weeks preparing the vehicle to return to the pad for the Artemis 1 launch.

That work includes inspecting and repairing a quick-disconnect fitting on the core stage that was the source of the hydrogen leak in the most recent WDR. Weber said they will likely replace a Teflon seal in that connector that has been there since the Green Run tests of the vehicle at the Stennis Space Center in 2020 and 2021. “It’s got some run time on it, as well as a couple trip to the pad, so we’re expecting we’re going to go in and change out those softgoods,” he said.

He acknowledged that might not correct the problem. If the hydrogen leak persists once the vehicle returns to the pad, the connection is in area that can be accessed while at the pad, enabling repairs without having to return the VAB.

Cliff Lanham, senior vehicle operations manager for NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems program, said he expected the vehicle to spend six to eight weeks in the VAB for the quick-disconnect repairs and other final work on SLS and Orion. That assumes the work doesn’t find any additional issues that require more work while in the building.

Once SLS returns to the pad, Lanham estimated it would take about 10 to 14 days to get ready for a launch, although it may be possible to condense that schedule somewhat based on the experience with the wet dress rehearsals.

That schedule, officials said, could still allow a launch in a window that runs from Aug. 23 through Sept. 6, although with no launch opportunities on Aug. 30, 31 or Sept. 1. The next window opens Sept. 19 and runs through Oct. 4.

“We think we’re really in good shape and we’re not working any major technical issues at this time. It’s strictly vehicle processing and getting ready to do a launch attempt,” said Whitmeyer.

He said it was too soon to set a window, citing upcoming reviews and assessment of work on the vehicle in the VAB. A launch in late August “is still on the table,” though, he added.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 4.07.2022

.

In a step closer to launch, NASA’s Artemis 1 moon rocket rolls back to hangar

NASA’s powerful new Space Launch System moon rocket was hauled from its launch pad back to the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center Saturday for final repairs, testing and closeouts, moving closer to liftoff later this summer after completing a fueling demonstration last month.

The 322-foot-tall (98-meter) moon rocket rolled off its posts at pad 39B at 4:12 a.m. (0812 GMT) Saturday, about five hours behind schedule to allow time for extra inspections. A diesel-powered crawler-transporter carried the Space Launch System rocket down the ramp and along the rock-covered crawlerway on the 4.2-mile (6.8-kilometer) journey back to the Vehicle Assembly Building.

The launcher rolled into High Bay 3 of the iconic assembly hangar around 2 p.m. EDT (1800 GMT), and was secured inside the VAB about a half-hour later.

The return of the SLS moon rocket to the Vehicle Assembly Building moves the Artemis 1 mission a step closer to launch on a test flight around the moon. After a decade in development costing more than $20 billion, the Artemis 1 mission will mark the first flight of the huge SLS moon rocket, sending an Orion crew capsule on a course to orbit the moon.

The test flight will not carry astronauts, but will be the first launch of a human-rated rocket and spacecraft to the moon since the Apollo program. If the Artemis 1 flight goes according to plan, NASA intends for the next SLS/Orion mission — Artemis 2 — to carry a crew of around on a loop around the far side of the moon and back to Earth in 2024, marking the first astronaut voyage to the moon since 1972.

Future Artemis missions will incorporate a commercial crew lander to ferry astronauts between the Orion spacecraft in lunar orbit and the surface of the moon.

NASA’s launch team fully loaded the moon rocket with cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants during a practice countdown June 20, accomplishing a major test objective managers wanted to complete before proceeding with final launch preps.

A series of practice countdown runs in April were plagued by technical problems that prevented the full fueling of the rocket.

The June 20 countdown rehearsal was not free of trouble. Engineers detected a hydrogen leak in a quick-disconnect fitting near the bottom of the rocket’s core stage, in a line that dumps excess hydrogen overboard from the system to thermally condition the four RS-25 main engines for ignition.

The launch team overcame the problem and continued the countdown to T-minus 29 seconds, about 20 seconds before the time engineers wanted to reach in the dress rehearsal. One of the final test objectives not accomplished June 20 was a hot-fire of hydraulic pumps powering the steering mechanisms on the rocket’s two solid-fueled boosters, which provide 80% of the steering control for the first two minutes of launch.

NASA ground teams successfully activated the hydraulic power units during a separate test June 25, paving the way for crews to prep the rocket for rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building.

The return to the rocket hangar was supposed to begin late Thursday, but NASA pushed back the move by a day to complete work on the slope of the crawler way leading to the launch pad. Teams completed grating, or sifting, the crawlerway using heavy equipment before going ahead with rollback Friday night.

The crawler reached a top speed of nearly 1 mph during the trip back to the VAB. The combined stack of the SLS moon rocket, its mobile launch platform, and the crawler vehicle weighs about 21.4 million pounds.

NASA’s ground team briefly stopped the crawler and the SLS moon rocket outside the VAB around midday Saturday, allowing time for the crew access arm on the mobile launcher tower to move into position next to the Orion crew capsule on top of the vehicle.

The access arm is retracted against the mobile launcher tower while it is in motion, and can’t be extended once the rocket is inside the assembly building.

With the arm extended, the crawler continued moving through the vertical door of High Bay 3. The transporter’s jacking and leveling system lowered the mobile launch platform onto pedestals inside the VAB to complete the journey from pad 39B.

The space agency has not formally set a target launch date for the first SLS moon rocket, but officials are aiming to have the launcher ready to blast off on the Artemis 1 test flight in late August or early September, when the alignment of the moon, the sun, and the Earth will enable the mission to meet all its objectives.

A launch period opens Aug. 23 and runs until Sept. 6. NASA has another launch period available beginning Sept. 19 and extending until Oct. 4, followed by three more two-week launch periods through the end of the year. Depending on when the Artemis 1 mission takes off, the Orion test flight could last roughly 26 days or as long as 42 day. The mission duration hinges on the location of the moon relative to Earth, allowing the Orion spacecraft to complete a half-orbit or one-and-a-half distant orbits around the moon.

The launch periods are constrained by a number of considerations, including the position of the moon in its orbit around Earth, limits on how long the Orion spacecraft can fly in shadow without direct sunlight on its solar arrays, and re-entry and splashdown rules, including a requirement for a daytime return to Earth to aid in recovery operations in the Pacific Ocean.

The launch windows for the Aug. 23-Sept. 6 window are posted below. Aug. 30, Aug. 31, and Sept. 1 not viable launch dates because not all of the launch window constraints are met for those days.

Once the rocket is back inside the assembly building, workers will extend 10 sets of access platforms to reach various levels of the launch vehicle, and erect an access stand to reach the leaky hydrogen line.

Aside from already-planned work to ready the rocket for launch, technicians will repair the leaky hydrogen connector discovered during the fueling demonstration last month. Workers will replace Teflon seals on quick-disconnect fittings in the tail service mast umbilical, the connection that routes cryogenic propellants between the mobile launch platform and the SLS core stage.

Officials believe one of those seals loosened in the 4-inch quick-disconnect that started leaking during the June 20 countdown rehearsal. Phil Weber, an integration manager on the Artemis ground operations team, said last week that workers will also likely change out a similar seal on a larger 8-inch propellant fill and drain line as a pre-emptive measure.

Other work inside the VAB will include changing out an avionics box on the SLS upper stage, and a software load on the upper stage computer. The ground crew will also stow final equipment inside the pressurized cabin on the Orion spacecraft, and install flight batteries on the core stage, boosters, and second stage, according to Cliff Lanham, the Artemis 1 flow director on NASA’s ground operations team at Kennedy.

“Then, ultimately, we want to do our flight termination system testing, and once that’s complete, we’ll be able to perform our final inspections on all the volumes of the vehicle and do our closeouts,” Lanham said in a June 24 press briefing.

The flight termination system consists of pyrotechnic charges on the rocket that would be fired to destroy the vehicle if it veered off course and threatened populated areas.

The ground crew inside the VAB will arm the flight termination system and perform an end-to-end test, demonstrating the ability of the Space Force’s range safety team to send a destruct command to the SLS moon rocket. The flight termination system is only certified for 20 days after completion of the test, and the rocket would need to be hauled back to the VAB to revalidate the destruct mechanisms.

According to Lanham, work on the SLS moon rocket inside the Vehicle Assembly Building will take about six to eight weeks.

Weber said the ground crew will be “hustling” to roll the rocket back to pad 39B after the flight termination system check. The rocket will need to spend 10 to 14 days on the pad before the first launch attempt, and the schedule currently shows the Artemis 1 team could fit in three launch attempts before the 20-day flight termination system certification clock expires.

NASA officials are expected to set a target launch date as soon as next week.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 21.07.2022

.

NASA to Discuss Status of Artemis I Moon Mission

NASA will hold a media teleconference at 11 a.m. EDT Wednesday, July 20, to discuss next steps for the Artemis I mission with the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Audio of the call will livestream on NASA’s website.

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy, technicians continue to prepare SLS and Orion for Artemis I. The first in a series of increasingly complex missions, Artemis I will be an uncrewed flight test that will provide a foundation for human exploration in deep space and demonstrate our commitment and capability to extend human existence to the Moon and eventually Mars.

Teleconference participants include:

- Jim Free, associate administrator, Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, NASA Headquarters in Washington

- Cliff Lanham, senior vehicle operations manager, Exploration Ground Systems Program, Kennedy

- Mike Sarafin, Artemis mission manager, NASA Headquarters

To participate by telephone, media must RSVP no later than two hours prior to the start of the event to: ksc-newsroom@mail.nasa.gov.

Through Artemis missions, NASA will land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon, paving the way for a long-term lunar presence and serving as a steppingstone to send astronauts to Mars.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 23.07.2022

.

NASA to Host Media Activities in Houston Ahead of Lunar Mission

Ahead of the Artemis I flight test, NASA is inviting media to its Johnson Space Center in Houston Friday, Aug. 5, for a detailed mission briefing and a behind-the-scenes look at facilities that will enable a long-term human presence at the Moon.

NASA is currently targeting no earlier than Monday, Aug. 29, for the launch of the Space Launch System rocket to send the Orion spacecraft around the Moon and back to Earth. The mission will take place over the course of about six weeks to check out systems before crew fly aboard on Artemis II.

The media day will feature mission support facilities, trainers, and hardware for future Artemis missions, as well as interview opportunities with program leaders, flight directors, astronauts, scientists, and engineers. It also will feature tours and activities in unique facilities at Johnson.

U.S. media interested in participating in person at Johnson must contact the Johnson newsroom no later than 5 p.m. Friday, July 29, by calling: 281-483-5111 or emailing: jsccommu@mail.nasa.gov. International media must contact the Johnson newsroom no later than 5 p.m. Tuesday, July 26.

Planned activities include:

- In-depth mission briefing – Discuss the Artemis I mission profile with flight directors and mission experts. The briefing also will air on NASA TV and media may ask questions by phone. NASA will share the briefing time and details to join by phone at a later date.

- Artemis mission control – Chat with flight directors, engineers and astronauts while in the control room that will be used throughout the Artemis I mission.

- Space Vehicle Mockup Facility – View a full scale version of the Orion crew module used for training and an Orion launch and entry suit that will be worn by astronauts on future Artemis missions.

- Systems Engineering Simulator – Preview the first Artemis lunar surface excursions in a new virtual reality trainer that is preparing future moonwalkers for extravehicular lunar surface operations.

- Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory – Learn about the latest hardware and ongoing testing in one of the world’s largest swimming pools to support Artemis missions.

- Gateway high-fidelity hardware mockup fabrication facility – Tour a high-fidelity mockup of Gateway’sHabitation and Logistics Outpost module where Artemis astronauts will live and work during future Artemis missions.

- Additional interview opportunities – Speak with experts from various programs at Johnson that support NASA’s Artemis missions, including the Extravehicular Activity and Human Surface Mobility Program and the Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative.

Artemis I is an uncrewed flight test, the first in a series of increasingly complex missions to the Moon in preparation for human missions to Mars. Through Artemis missions, NASA will land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon, paving the way for a long-term lunar presence and serving as a steppingstone to send astronauts to Mars.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 29.07.2022

.

NASA to Host Briefings to Preview Artemis I Moon Mission

A brilliant blue sky serves as a backdrop for the Artemis I Space Launch System (SLS) and Orion spacecraft atop the mobile launcher at Launch Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on June 30, 2022.

NASA will host a pair of briefings on Wednesday, Aug. 3, and Friday, Aug. 5, to preview the upcoming Artemis I lunar mission. The agency is currently targeting no earlier than Monday, Aug. 29, for the launch of the Space Launch System rocket to send the Orion spacecraft around the Moon and back to Earth. The mission will take place over the course of about six weeks to check out systems before crew fly aboard on Artemis II.

The first briefing will provide an overview of the Artemis I mission, and the second briefing will dive deeper into the Artemis I mission timeline and spacecraft operations. Both briefings will air live on NASA Television, the NASA app, the agency’s website.

Briefing participants include (all times Eastern):

Wednesday, Aug. 3

11 a.m. – Artemis I mission overview briefing with the following participants:

- NASA Administrator Bill Nelson

- Bhavya Lal, associate administrator for technology, policy, and strategy, NASA Headquarters

- Mike Sarafin, Artemis I mission manager, NASA Headquarters

- Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, Artemis I launch director, NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida

- John Honeycutt, Space Launch System program manager, NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama

- Howard Hu, Orion program manager, NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston

This event will air live on NASA TV and media may join by telephone to ask questions. To participate by phone, media must send their full name, media affiliation, email address, and phone number no later than two hours prior to the start of the event to: kathryn.hambleton@nasa.gov.

Friday, Aug. 5

11:30 a.m. – Artemis I detailed mission briefing with the following participants:

- Debbie Korth, Orion program deputy manager, NASA Johnson

- Rick LaBrode, lead Artemis I flight director, NASA Johnson

- Judd Frieling, Artemis I ascent/entry flight director, NASA Johnson

- Melissa Jones, Artemis I recovery director, NASA Kennedy

- Reid Wiseman, chief astronaut, NASA Johnson

- Philippe Deloo, Orion European Service Module program manager, ESA (European Space Agency)

This event will air live on NASA TV and media may participate in person at Johnson or by phone. To participate in the briefings by phone, media must contact the Johnson newsroom by 5 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 4. U.S. media interested in participating in person at Johnson must contact the Johnson newsroom no later than 5 p.m. Friday, July. 29, by calling: 281-483-5111 or emailing: jsccommu@mail.nasa.gov.

Along with the briefings, NASA will host an Artemis I media day at Johnson Friday, Aug. 5, to showcase Artemis I mission hardware and offer interviews. Media attending will get an in-person look at development mockups, design simulators, flight control operations, and hardware in development for lunar exploration.

Artemis I is an uncrewed flight test, the first in a series of increasingly complex missions to the Moon.

Through Artemis missions, NASA will land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon, paving the way for a long-term lunar presence and serving as a steppingstone to send astronauts to Mars.

Quelle: NASA