20.03.2022

Nature proves truth is still stranger than fiction: A pulsar has shot energetic particles in a thin, straight line that extends for light-years into space. The discovery might explain how antimatter makes its way to Earth.

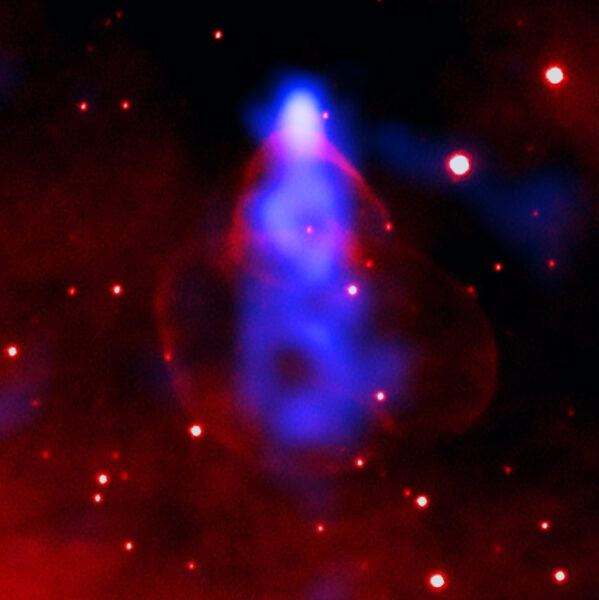

This image, 2.7 light-years across, shows part of a pulsar's "phaser blast," a beam of particles extending to the lower right. Additional observations revealed its true extent to be 7 light-years long. The pulsar, its particle wind, and its jet all glow in X-rays (blue). The pulsar's environment and bow shock are also imaged in visible light (red). (The white box shows the area covered by the close-up image of the pulsar below.)

X-ray: NASA / CXC / Stanford Univ. / M. de Vries; Optical: NSF / AURA / Gemini Consortium

Star Trek can keep its ray guns — pulsars make far more powerful beams of radiation.

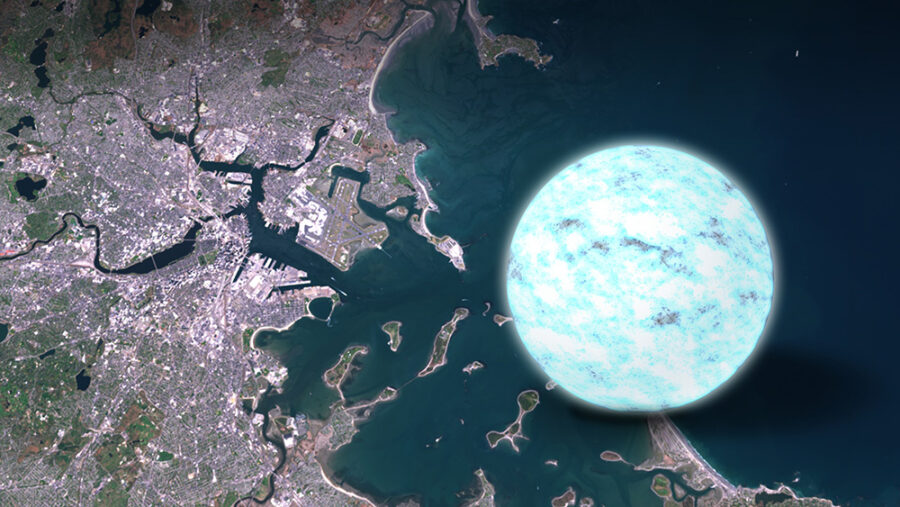

Crushed stellar cores, left behind when a massive star goes supernova, are among nature’s own particle accelerators. Though pulsars are only the size of Manhattan, their dizzying spins and powerful magnetic fields can energize particles to a significant fraction of the speed of light. In addition, pulsars glow with high-energy radiation, which can itself convert into pairs of electrons and their antimatter counterpart, positrons.

That’s why astronomers often point to pulsars as a primary source of the antimatter detected at Earth. For example, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer aboard the International Space Station has detected a surprising amount of positrons. But the same magnetic fields responsible for accelerating particles also act to cage them, so some have suggested the excess AMS found may be a signal not from pulsars but from dark matter.

However, one pulsar shows a possible means for particles to escape their confines.

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

PSR J2030+4415 is a city-size core that whirls around three times every second, 1,630 light-years away in Cygnus, the Swan. In 2020, Martijn de Vries and Roger Romani (both at Stanford University) observed this pulsar using the Chandra X-ray Observatory. In addition to the pulsar itself and the glowing particles around it, they saw a thin, straight line of X-ray emission connected to the pulsar.

X-ray: NASA / CXC / Stanford Univ. / M. de Vries; Optical: NSF / AURA / Gemini Consortium

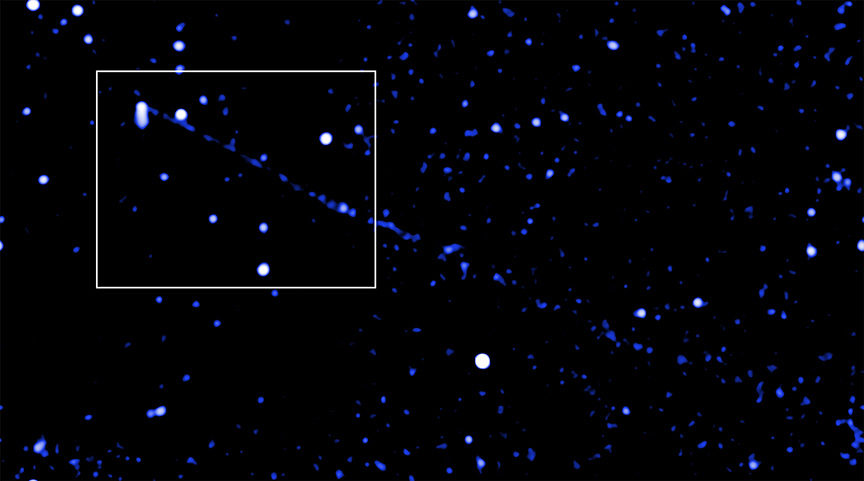

The beam trails off the edge of the discovery image in a celestial version of Harold’s purple crayon. So De Vries and Romani asked Chandra to return for additional observations to determine the beam’s true extent (more pages for Harold), and found that it stretches 15 arcminutes across the sky, or 7 light-years long.

“It's amazing that a pulsar that's only 10 miles across can create a structure so big that we can see it from thousands of light-years away,” says de Vries. “With the same relative size, if the filament stretched from New York to Los Angeles the pulsar would be about 100 times smaller than the tiniest object visible to the naked eye.”

X-ray: NASA / CXC / Stanford Univ. / M. de Vries

The team also obtained visible-light images using the Gemini telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawai'i. The images show hydrogen-alpha light emitted from hydrogen atoms ionized by the pulsar's energy.

Together, the visible-light and X-ray emissions from the gas and particles around the pulsar tell the story of the beam's creation. The stellar core was hurtling along through space, preceded by a bow shock (like the bow wave that crests ahead of a motorboat), until some 20 to 30 years ago. That was when something, perhaps a denser medium, slowed the bow shock.

“The pulsar itself is like a bullet that weighs about 1.5 times the Sun’s mass,” Romani explains, “so it didn’t feel the density increase at all. It caught up to and punched through the stalled bow shock and kept going.”

The breakthrough briefly aligned the pulsar’s own magnetic field lines with those of the larger galaxy, allowing a thin thread of particles to escape the pulsar’s clutches. Because the breakthrough took place in an astronomical blink of the eye (about 12 years, the researchers estimate), the particles are essentially lighting up one of the galaxy’s magnetic field lines.

“This discovery also has broader implications on how electrons and positrons can escape from their parent pulsars,” says astrophysicist Kaya Mori (Columbia University), who was not involved in the study. “The enigmatic origin of the positron excess observed at Earth could be associated with PSR J2030+4415 and other pulsar filaments yet to be discovered.”

Events such as this one might help explain how antimatter can escape and spread through the galaxy. “We can already see that the filaments spread with distance from the pulsar,” Romani says. “Certainly, pulsars are a more prosaic explanation for the AMS positrons than dark matter annihilation.”

Granted, observations of such breakthrough events are rare — this is only the fourth pulsar known to have produced a long, narrow filament — but that may be because these events are so brief. They may have occurred throughout our galaxy’s history.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope