18.03.2022

As Saturn returns to the morning sky, will this otherwise serene-looking planet experience another bout of severe weather? Keep your eyes peeled for white spots!

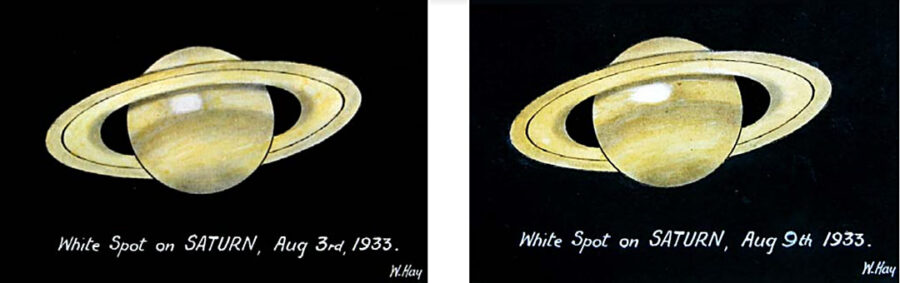

Will Hay, a beloved British comedian and entertainer, was also an ardent amateur astronomer. Hay independently discovered a white spot outbreak on Saturn with his 6-inch Cooke refractor from London on August 3, 1933. Observers should keep their eyes peeled for the return of similar activity during the current apparition.

Will Hay, courtesy of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) and Martin Mobberley

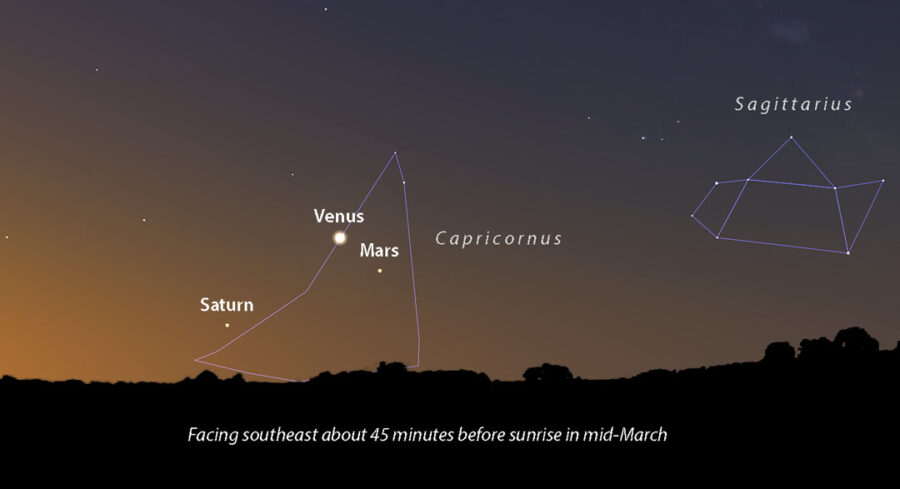

Bright planets have deserted dusk this season and instead flocked like robins to the dawn sky. Venus and Mars have been steady companions for weeks, with Saturn just now entering the scene. I got my first look at the ring king on March 3rd paired with Mercury 45 minutes before sunup. Through my scope, Saturn was a quivering blob. But I held out until the planet rose high enough for the rings to steady and sharpen, marking (for me) the official start of the 2022 apparition.

Bob King

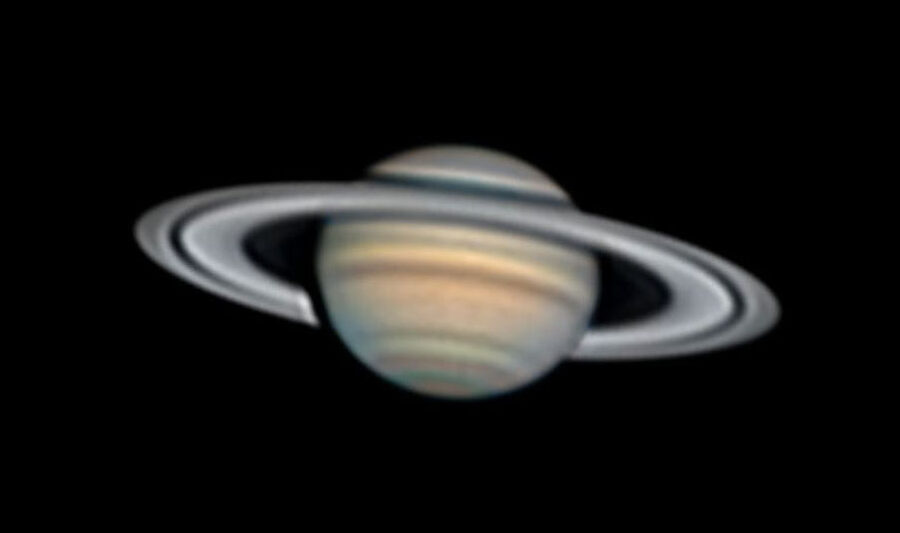

Every planetary apparition is a chance to make a start fresh and set new observing goals. With Mars, this might be the year to spot both polar caps or identify a dark albedo feature you've never seen before. While Saturn's rings are undeniably captivating, let me suggest diverting some of your attention this apparition to its globe in anticipation of the next Great White Spot outbreak.

Lucca Schwingel Viola

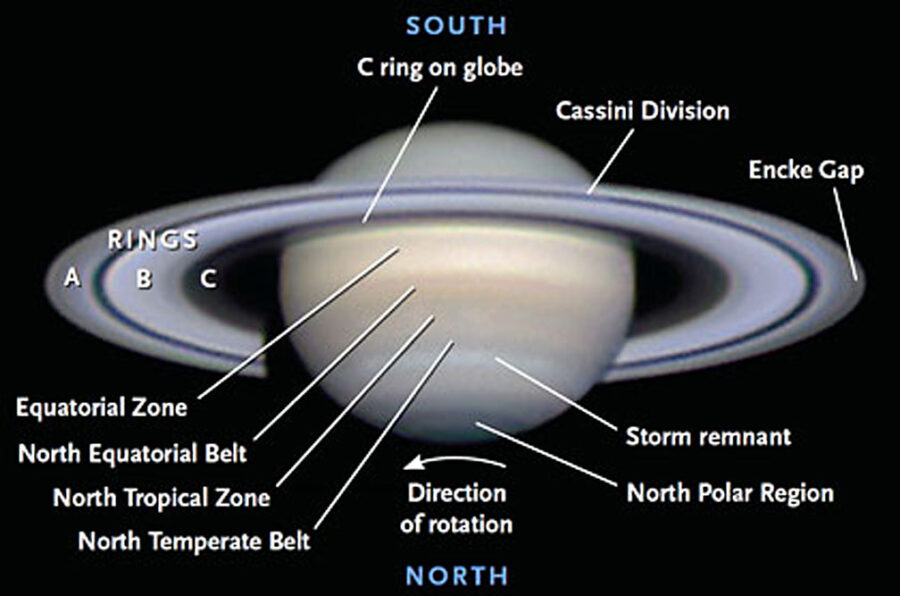

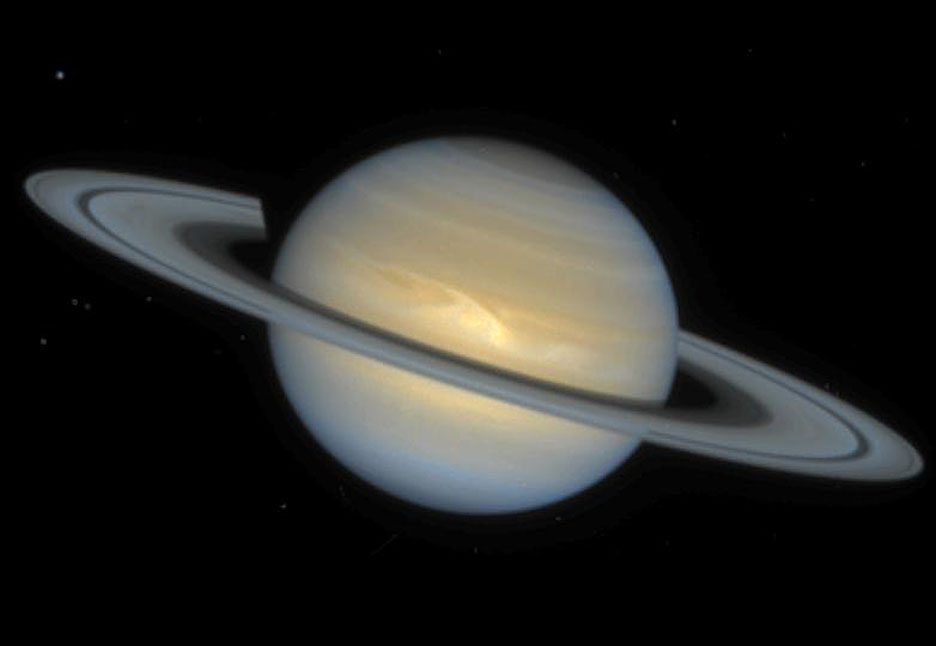

Saturn looks pretty bland when compared to its bigger brother, Jupiter. Being more massive, Jupiter compresses its atmosphere into a layer about 75 kilometers thick, so ammonia-ice clouds form closer to the top of its airy envelope, where they're fair game for visual observers. Due to Saturn's lower gravity, its atmosphere is thicker — clouds form at a deeper level beneath a layer of photochemical haze, making them more difficult to see. Enhanced images clearly show numerous dark belts, bright zones, and occasional spots resembling Jovian features — but they're so muted, Saturn's globe appears barren in contrast.

Like many amateurs my view of Saturn resembles Will Hay's sketch (above) — a bland, pale yellow globe encircled by a grayish-brown equatorial belt, a brighter equatorial zone, and topped by a gray hood. On rare occasions of excellent seeing I've glimpsed the north and south components of the North Equatorial Belt and suspected one or two additional bands and zones.

Courtesy of Martin Mobberley

But every 20 to 30 years, Saturn awakens from its visual dormancy and unleashes a powerful storm that lofts water and other molecules high into the atmosphere where they freeze out to form a large, white cloud. These Great White Spots have appeared at somewhat regular intervals since the first recorded observation by American astronomer Asaph Hall on December 7, 1876. Hall, best known as the discoverer of Martian moon Deimos and Phobos, observed a very bright, round spot 2–3″ in diameter in Saturn's Equatorial Zone that remained visible for nearly a month.

Will Hay, courtesy of the RAS and Martin Mobberley

Additional major eruptions occurred in 1903, 1933, 1960, 1990, and 2010, with a number of smaller spots recorded photographically (on the ground and from space) in recent years including a moderate-size storm in 1994. British entertainer and passionate amateur Will Hay made one of the most celebrated sightings in 1933. He noticed a large, bright elliptical spot in the planet's Equatorial Zone through his 6-inch refractor on the night of August 3rd. He immediately rang up his friend and fellow amateur W. H. Steavenson, who confirmed the observation. Hay used successive transits of the spot to measure Saturn's equatorial rotation period at approximately 10 hours 17 minutes. The modern value is closer to 10 hours 14 minutes.

NASA / JPL / STScl

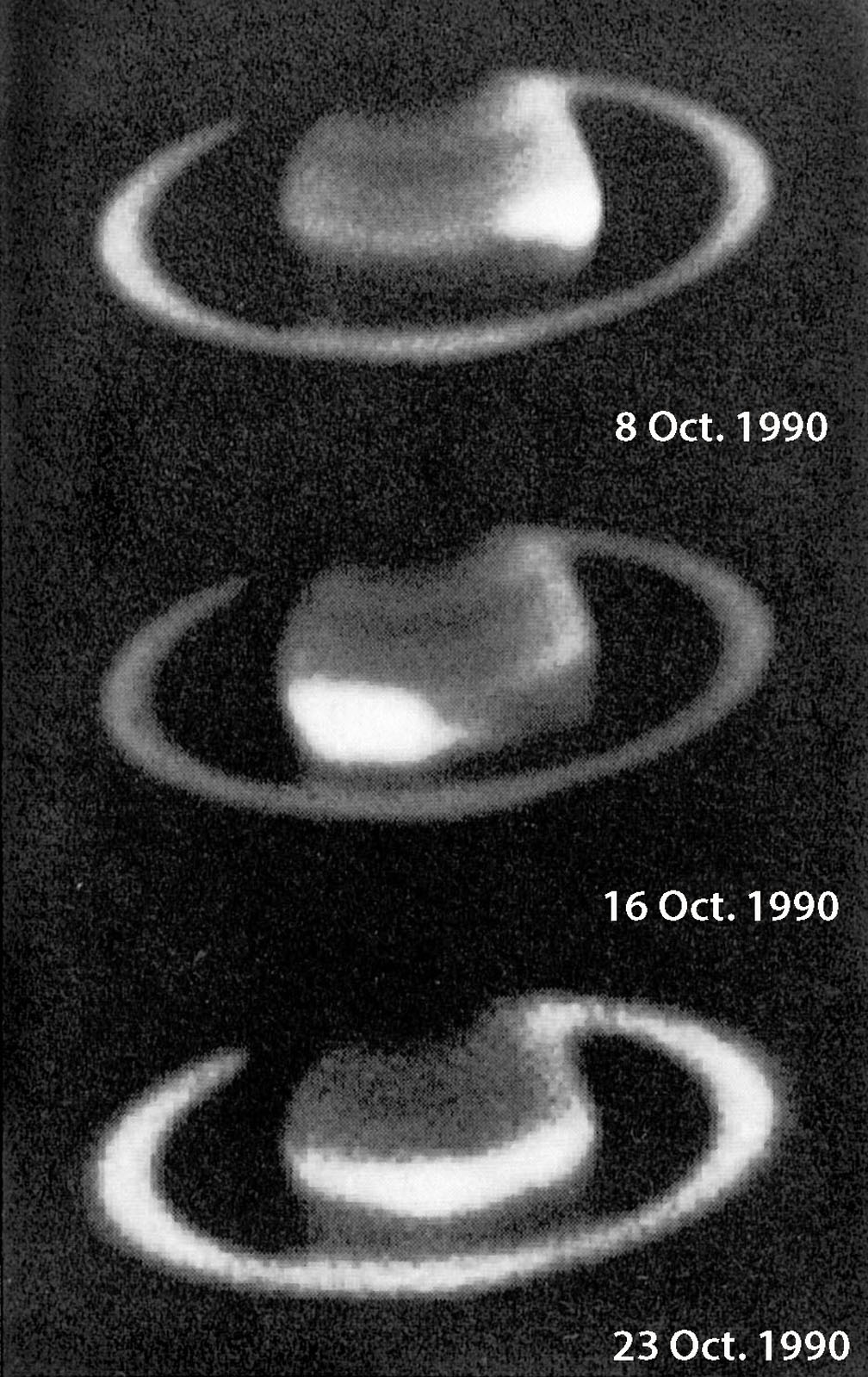

Great White Spot appearances have alternated between the equatorial region and mid-northern latitudes and may be connected to seasonal changes Saturn experiences during its 29.5-year orbital period . . . or not. The recent 1994 and 2010 eruptions break that pattern, making it all that more important to keep a close eye on the planet during this and other off-year apparitions.

European Southern Observatory

The Great White Spot of 1990 was widely observed by amateurs, including myself. On October 12th of that year, using an 8-inch f/6 Dob, "the white spot was the brightest feature on Saturn, as bright or perhaps brighter than the outer B-ring," according to my observing notes. I remember being glued to the eyepiece as the core of the storm crossed the planet's central meridian, making it "the first time I'd ever watched anything on Saturn (its globe) move!" We often take Jupiter's east-to-west parade of meteorological curiosities for granted. Saturn requires the patience of Yoda, but the reward is great.

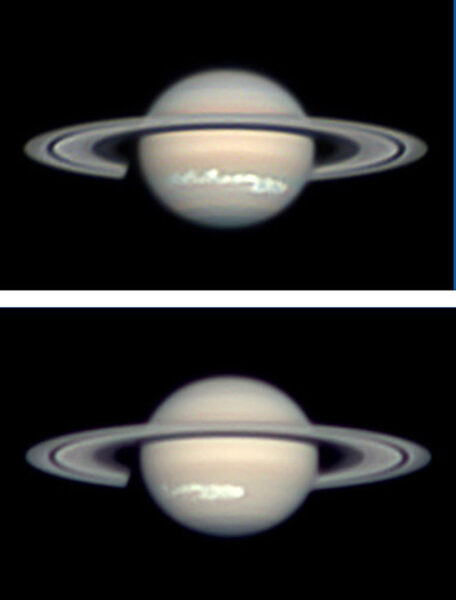

Amateurs have been instrumental in discovering and alerting professionals to the appearance these huge storms. Starting in 1933, they were the first to spot and report all major outbreaks. That includes the monster storm of 2010, discovered by amateurs Sadegh Ghomizadeh and Teruaki Kumamori on December 8th and 9th in Saturn's North Tropical Zone (NTrZ). By January 5, 2011, it had spread across more than 100° of longitude and resembled a thick plume of smoke billowing from a steam locomotive.

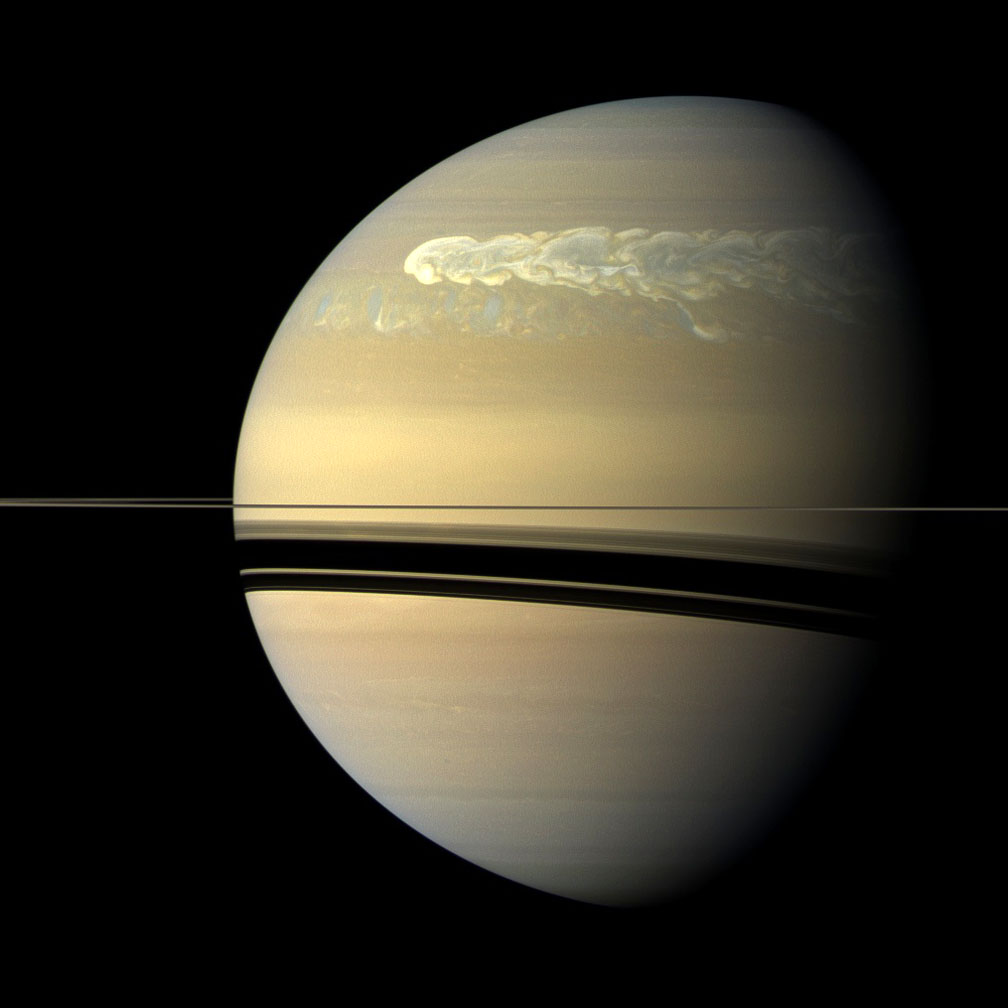

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SSI

Good thing it appeared 10 years early. As it happened, NASA's Cassini probe had a front-row seat at the planet and sent back spectacular, close-up images of roiling clouds and the storm "chasing its tail" around the globe. With its radio and plasma wave science instrument the probe detected 10 lightning strikes per second at the height of the storm that were 10,000 times more powerful than those on Earth.

What's at the bottom of these atmospheric hiccups? Saturn's air column is comprised of layers, with the outer atmosphere resting on top of denser air made of hydrogen, helium and water molecules. The outer layer acts like a lid that prevents the warmer air underneath from rising, cooling and condensing into turbulent storm clouds. Over time, that layer radiates its heat into space until it finally becomes cold and dense enough to sink, allowing the warm, water-rich air sequestered below to punch through to the top and blow up into a titanic thunderstorm.

Stellarium

The heavier water molecules eventually rain back down, the storm calms and quiescence returns until the balance shifts again. There's no knowing if and when the next Great White Spot might appear, but if you subscribe to the ~30-year periodicity hypothesis, it should have occurred in 2020 or will again in 2040. No matter when it happens I'll put my money on amateurs like you spotting it first.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope