25.02.2022

Russia's invasion of Ukraine late Wednesday has yet again raised concerns about the country's relationship with the United States in space, where it has historically remained stable.

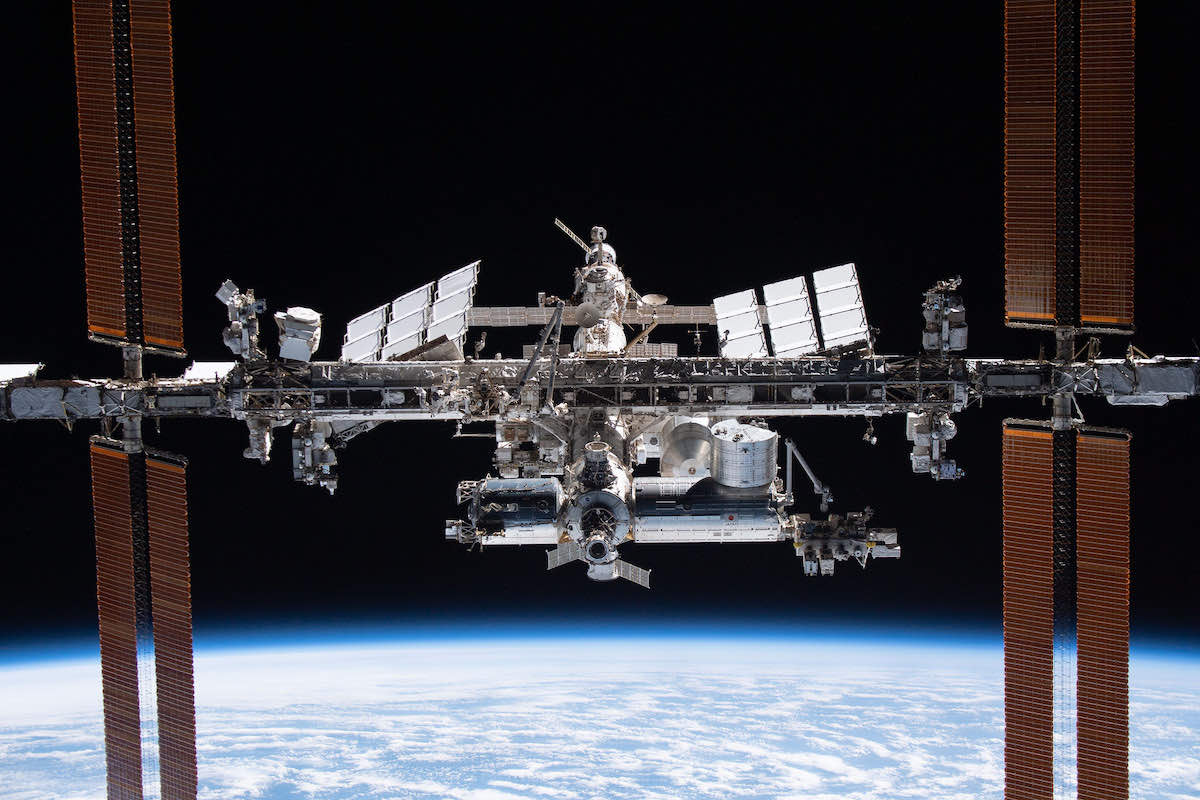

Four NASA astronauts, two Russian cosmonauts, and one European Space Agency astronaut are stationed aboard the International Space Station, their home away from home whizzing by at 17,500 mph as Russian forces continue moving into Ukraine. The U.S. and Russia's decades-long partnership in space has historically been one of the more stable elements of the two superpowers' relations, regardless of what happens on the ground.

In a statement to FLORIDA TODAY, NASA's Jackie McGuinness on Thursday said the agency "continues working with Roscosmos and our other international partners in Canada, Europe, and Japan to maintain safe and continuous International Space Station operations."

Stationed aboard the ISS right now are NASA astronauts Kayla Barron, Raja Chari Thomas Marshburn, and Mark Vande Hei; European Space Agency astronaut Matthias Maurer; and Russian cosmonauts Anton Shkaplerov and Pyotr Dubrov.

The chief of Roscosmos, the state corporation responsible for spaceflight, issued a statement Wednesday and said he values the NASA relationship but feels conflicted about other areas of U.S. policy.

"We greatly value our professional relationship with NASA, but as a Russian and a citizen of Russia, I am completely unhappy with the sometimes openly hostile U.S. policy towards my country," Dmitry Rogozin said just before the invasion.

In his first speech since the invasion, meanwhile, President Biden on Thursday said new sanctions levied against Russia will target "the aerospace industry, including their space program."

The ISS has been continually occupied since 2000. Hundreds of people from several countries have conducted scientific research onboard, and the station's hardware is just as diverse – neither the Russian nor American segments are self-sufficient and rely on each other for everything from power to communications.

For the time being, the U.S. side has an advantage compared to just a few years ago: SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule. It stands as NASA's only access to the ISS without reliance on the Russians, giving the agency some leverage.

For nearly 10 years after the end of the shuttle program in 2011, NASA paid Russia to ferry U.S. astronauts to the space station. For some missions, it still does.

Before the invasion, the two countries were discussing flying cosmonauts on Crew Dragon in the future, but the status of those talks is unclear.

Officials for decades have been prepared for political turmoil to rattle operations in space, where the cost of entry has led to partnerships like the ISS. Russia's invasion of Ukraine isn't the first time tensions have led to questions.

Just three months ago, the Russian military fired an anti-satellite weapon that destroyed an old spacecraft, sending a massive debris field too close to the ISS for comfort. The crew had to take shelter in capsules as the field passed by. In 2014, astronauts and cosmonauts were put in a similar situation when Russian invaded and subsequently annexed Crimea from Ukraine.

Going back to the height of the Cold War, both partnered on Apollo-Soyuz, the first international space mission that saw two capsules from different countries dock in 1975. Millions watched the orbital meeting that potentially signified a more peaceful relationship in space for the two superpowers.

Looking ahead, however, the ISS partnership could see a changing dynamic. NASA ultimately hopes to transfer the aging outpost into the hands of private industry sometime in the next decade while it focuses resources toward missions beyond Earth orbit.

Quelle: Florida Today

+++

Biden: Sanctions will “degrade” Russian space program

This is a developing story. Follow @SpaceNews_Inc for the latest and check back for updates.

WASHINGTON — Russia’s space program won’t be shielded from U.S. sanctions in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, U.S. President Joe Biden said Thursday afternoon.

“We estimate that we will cut off more than half of Russia’s high-tech imports, and it will strike a blow to their ability to continue to modernize their military. It will degrade their aerospace industry, including their space program,” Biden said in a White House address outlining new sanctions.

A White House fact sheet released Feb. 24 did not elaborate on specific sanctions or restrictions for Russia’s space program. The administration said it is imposing “Russia-wide denial of exports of sensitive technology, primarily targeting the Russian defense, aviation, and maritime sectors to cut off Russia’s access to cutting-edge technology.” Examples of such technologies include semiconductors, telecommunication, encryption security, lasers, sensors, navigation, avionics and maritime technologies. “These severe and sustained controls will cut off Russia’s access to cutting edge technology,” the fact sheet stated.

In a brief statement late Feb. 24, NASA said the new export restrictions would not affect its work with its Russian counterpart, Roscosmos, of operations of the International Space Station. “The new export control measures will continue to allow U.S.-Russia civil space cooperation,” the agency stated. “No changes are planned to the agency’s support for ongoing in orbit and ground station operations.”

In London, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said civil space cooperation with Russia could be impacted. “We will have to see what further downstream effects there are on collaboration of all kinds. I must say that hitherto I have been broadly in favor of continuing artistic and scientific collaboration. But in the current circumstances, it’s hard to see how even those can continue as normal.”

Johnson was responding to a question asked in Parliament about the implications of Russia’s invasion for cooperation involving the International Space Station.

Biden’s statement prompted a sharp rebuke from Dmitry Rogozin, director general of Roscosmos and former deputy prime minister of Russia. In a series Russian language tweets, he noted that the U.S. had already blocked imports of radiation-hardened electronics and made it difficult for Western nations to procure commercial launches on Russian rockets. “We are ready to act here, too,” he said regarding launch restrictions.

Rogozin also raised questions about the future of the International Space Station. “Do you want to destroy our cooperation on the ISS?” he asked, noting that the station’s orbit is maintained by thruster firings on the Russian segment of the station, primarily by Progress cargo spacecraft. “If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit and fall into the United States or Europe?”

While the station depends on the Russian segment for propulsion, the U.S. segment provides key capabilities, like power, that the Russian segment lacks. Moreover, a Cygnus cargo spacecraft that arrived at the station Feb. 21 will conduct a test in April of reboosting the station as an alternative to Progress spacecraft.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has affected the operations of one U.S.-based launch vehicle developer. Launcher said Feb. 24 that it relocated 10 engineers in a Ukraine-based office, along with their immediate families, to Sofia, Bulgaria. It is also supporting six employees who elected to remain in Ukraine. Those engineers have been working on the design of the engine Launcher is developing for its Launcher Light small launch vehicle. Launcher added that it has no investment ties to either Russia or Ukraine.

Computer translation of Dmitry Rogozin’s Feb. 24 tweet thread:

“Biden said the new sanctions would affect the Russian space program. OK. It remains to find out the details: 1. Do you want to block our access to radiation-resistant space microelectronics? So you already did it quite officially in 2014.As you noticed, we, nevertheless, continue to make our own spacecraft. And we will do them by expanding the production of the necessary components and devices at home.

“2. Do you want to ban all countries from launching their spacecraft on the most reliable Russian rockets in the world? This is how you are already doing it and are planning to finally destroy the world market of space competition from January 1, 2023 by imposing sanctions on our launch vehicles. We are aware. This is also not news. We are ready to act here too.

“Do you want to destroy our cooperation on the ISS? This is how you already do it by limiting exchanges between our cosmonaut and astronaut training centers. Or do you want to manage the ISS yourself? Maybe President Biden is off topic, so explain to him that the correction of the station’s orbit, its avoidance of dangerous rendezvous with space ..garbage, with which your talented businessmen have polluted the near-Earth orbit, is produced exclusively by the engines of the Russian Progress MS cargo ships. If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit and fall into the United States or…Europe? There is also the option of dropping a 500-ton structure to India and China. Do you want to threaten them with such a prospect? The ISS does not fly over Russia, so all the risks are yours. Are you ready for them?

“Gentlemen, when planning sanctions, check those who generate them for illness Alzheimer’s. Just in case. To prevent your sanctions from falling on your head. And not only in a figurative sense. Therefore, for the time being, as a partner, I suggest that you do not behave like an irresponsible gamer, disavow the statement about “Alzheimer’s sanctions”. Friendly advice”

Quelle: SN

+++

Biden announces sanctions targeting Russia’s space program

President Biden said Thursday the United States is imposing new sanctions against Russia, including measures that will “degrade” the country’s space program, in response to Russian military attacks on Ukraine.

So far, operations and training for future missions on the International Space Station are proceeding without interruption, according to NASA. The space station, an investment of more than $100 billion in U.S. taxpayer funding, has been continuously staffed by U.S. and Russian crew members since 2000.

NASA said in a statement that the new export control measures against Russia announced Thursday “will continue to allow U.S.-Russia civil space cooperation.”

“No changes are planned to the agency’s support for ongoing in orbit and ground station operations,” NASA said.

Relations between the United States and Russia have frayed since the dawn of the space station program. But the space station remains one of the most significant geopolitical partnerships left between the two countries.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine Thursday could threaten the long-term future of the partnership.

Biden himself singled out Russia’s space program in a speech Thursday, alongside other sectors of the Russian economy targeted by new sanctions. Biden said the measures will have “severe costs” on the Russian economy and are “purposely designed” to maximize long-term impacts on Russia.

“Between our actions and those of our allies and partners, we estimate that we’ll cut off more than half of Russia’s high tech imports and will strike a blow to their ability to continue to modernize their military,” Biden said. “It’ll degrade their aerospace industry, including their space program.”

Biden said the sanctions also targeted Russia’s military, maritime industry, financial institutions and Russian citizens close to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The sanctions, in sum, will be a “major hit to Putin’s long term strategic ambitions, and we’re preparing to do more,” Biden said.

A White House fact sheet on the new sanctions does not explicitly mention Russia’s space program, but discusses a ban on exports on “sensitive technology” to Russia’s defense, aviation, and maritime sectors.

“This includes Russia-wide restrictions on semiconductors, telecommunication, encryption security, lasers, sensors, navigation, avionics and maritime technologies,” the White House said.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who also announced his country was introducing new sanctions against Russia, was asked about the International Space Station program Thursday in the House of Commons.

He said he has been in favor of continuing “artistic and scientific collaboration” with Russia. “But in the current circumstances, it’s hard to see how even those can continue as normal,” Johnson said.

Dmitry Rogozin, head of Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, tweeted a series of messages Thursday shortly after Biden’s remarks, but before NASA’s clarification that the new sanctions won’t impact civilian cooperation in space.

“Biden said the new sanctions would affect the Russian space program,” Rogozin tweeted, according to an online translator. “OK. It remains to find out the details: 1. Do you want to block our access to radiation-resistant space microelectronics? So you already did it quite officially in 2014.”

Rogozin was apparently referring to sanctions introduced by the Obama administration after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

“As you noticed, we, nevertheless, continue to make our own spacecraft,” Rogozin added. “And we will do them by expanding the production of the necessary components and devices at home.

“2. Do you want to ban all countries from launching their spacecraft on the most reliable Russian rockets in the world? This is how you are already doing it and are planning to finally destroy the world market of space competition from January 1, 2023, by imposing sanctions on our launch vehicles. We are aware. This is also not news. We are ready to act here, too.

“3. Do you want to destroy our cooperation on the ISS? This is how you already do it by limiting exchanges between our cosmonaut and astronaut training centers. Or do you want to manage the ISS yourself? Maybe President Biden is off topic, so explain to him that the correction of the station’s orbit, its avoidance of dangerous rendezvous with space garbage, with which your talented businessmen have polluted the near-Earth orbit, is produced exclusively by the engines of the Russian Progress MS cargo ships.”

In this tweet, Rogozin’s reference to “space garbage” seems to be aimed at SpaceX’s Starlink internet network. More than 2,100 Starlink satellites have launched to date for the global internet network run by Elon Musk’s space company, making Starlink the largest fleet of spacecraft ever put into orbit.

SpaceX’s Starlink network, along with other commercial satellite “mega-constellations” have been criticized before. Rogozin didn’t mention a Russian anti-satellite missile test last year that added thousands of pieces of space junk to busy orbital traffic lanes a few hundred miles above Earth.

NASA and Roscosmos are the two largest partners on the International Space Station, which could not easily operate without critical contributions from U.S. and Russian modules. The U.S. segment of the station generates the bulk of the lab’s electrical power and maintains the pointing of the complex in orbit.

Russia’s modules and Progress supply ships are the primary source of propulsion, maintaining the lab’s altitude and occasionally steering the space station out of the way of space debris. Russia is also planning to oversee the de-orbiting and disposal of the huge station — the largest spacecraft ever put into orbit — into the unpopulated ocean at the end of its service life, currently expected around 2030.

A Northrop Grumman Cygnus cargo freighter that arrived at the space station Monday will debut a new U.S. capability to reboost the orbit of the complex. But the Cygnus spacecraft is not intended to maneuver the space station away from space junk, or make major orbit adjustments.

“If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit and fall into the United States or Europe? There is also the option of dropping a 500-ton structure to India and China. Do you want to threaten them with such a prospect? The ISS does not fly over Russia, so all the risks are yours,” Rogozon tweeted Thursday. “Are you ready for them? Gentlemen, when planning sanctions, check those who generate them for illness Alzheimer’s. Just in case. To prevent your sanctions from falling on your head. And not only in a figurative sense.”

“Therefore, for the time being, as a partner, I suggest that you do not behave like an irresponsible gamer, disavow the statement about ‘Alzheimer’s sanctions.’ Friendly advice.”

Early Friday, after NASA signaled its intention to continue with Russia on the space station program, Rogozin tweeted: “As diplomats say, ‘our concerns have been heard.’”

“NASA confirmed its willingness to continue to cooperate with Roscosmos through ISS,” Rogozin tweeted. “In the meantime, we continue to analyze the new U.S. sanctions to detail our response.”

Rogozin’s aggressive and sarcastic tone is nothing new.

In 2014, in the wake of sanctions levied following Russia’s earlier incursion into Ukraine, Rogozin ridiculed claims that he personally profited from Russia’s space industry. Rogozin was placed on the U.S. sanctions list at the time, when was a Russian deputy prime minister overseeing the country’s defense and aerospace industries.

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 helped trigger a review of the the U.S. space industry’s use of Russian components.

The crisis hastened a move away from the U.S. military’s use of United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rockets, which are powered by Russian RD-180 main engines. ULA is retiring the Atlas 5 and is developing a replacement rocket, Vulcan Centaur, with U.S.-made engines produced by Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’s space company.

NASA was already working with SpaceX and Boeing on new human-rated crew ferry capsules.

“After analyzing the sanctions against our space industry, I suggest the U.S. delivers its astronauts to the ISS with a trampoline,” Rogozin tweeted in 2014.

Rogozin was referring to NASA’s use of Russian Soyuz spacecraft to ferry U.S. and allied astronauts to and from the International Space Station. During a gap on U.S. human spaceflight capability following the retirement of the space shuttle, NASA purchased seats on Soyuz crew capsules to transport astronauts until SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spaceship began launching crews to the station in 2020.

“The trampoline is working!” Musk joked after SpaceX’s first crew launch.

With SpaceX’s crew transportation capability now operational, and a Boeing crew capsule in testing, NASA is less reliant on Russia’s space program than it was in 2014, but is not entirely free of Russian influence.

NASA said in a statement Thursday that it continues working with international partners, including Russia, “to maintain safe and continuous International Space Station operations.”

A crew of seven is currently living and working on the station — four U.S. astronauts, two Russian cosmonauts, and a European Space Agency flight engineer.

A team of three Russian cosmonauts is scheduled to launch to the space station March 18 on a Soyuz rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. They will replace NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei, current station commander Anton Shkaplerov, and cosmonaut Pyotr Dubrov scheduled to return to Earth on a different Russian Soyuz spacecraft March 30.

Vande Hei and Dubrov will close out a 355-day mission on the space station, a record for a single spaceflight by a U.S. astronaut.

Training continues for future space station expeditions, NASA said.

“Two NASA astronauts completed training in Russia earlier in February prior to returning home,” the agency said in a statement. “As scheduled, there are three cosmonauts currently training at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston for space station missions.”

David Burbach, a professor of national security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College, said near-term ISS operations are not likely to be impacted by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“The station is so interconnected, the two countries so interdependent, there’s not much middle ground between cooperating or irreversibly abandoning ISS (and as Roscosmos head Dmitiry Rogozin tweeted today, then the 500 ton station reentering uncontrolled),” Burbach wrote in an email to Spaceflight Now.

“I’m sure the U.S. doesn’t want that, and I don’t think Putin wants it,” Burbach wrote, noting he was commenting on a personal basis, and not on behalf of the Navy. “That said, Putin is not much worried about international prestige, and Russia’s human spaceflight program does not pay off in prestige or in cash the way it used to. I suspect ISS is less important to Russia today than Americans are used to thinking, but still somewhat important.”

But the deterioration in U.S.-Russia relations could drive the countries’ space programs apart over time, and make the start of future cooperative projects unlikely, he said.

“Longer term, this change in relations makes it somewhat more likely that ISS is terminated sooner than 2030, and I’m sure will raise interest in the U.S. in encouraging the development of commercial stations,” Burbach wrote.

“Sanctions and the break in relations are likely to impact commercial and scientific engagement with Russia,” he wrote. “I can’t imagine ESA or NASA agreeing to new joint projects with Roscosmos anytime soon. Russia was already a declining presence in the commercial launch market, and whether due to sanctions or avoiding political risk, it’s unlikely they’ll get new business from Western companies.”

Quelle: SN

+++

Launcher relocates its Ukraine-based staff to Sofia, Bulgaria.

I’m distraught by the unprovoked Russian aggression in Ukraine. We are providing all of the necessary support we can think of to our team, partners, and their families and communities in Ukraine.

Launcher has a subsidiary office in Dnipro, Ukraine consisting of eleven engineers and five support team members. This amazing engineering team has been contributing to our E-2 liquid rocket engine design with permission via U.S. State Department Technical Assistance Agreement.

In the last 12 months, Launcher has also grown to 50 team members at our HQ in Hawthorne (Los Angeles, CA).

As a precaution given the escalating political situation, during the last few weeks, we successfully relocated our Ukraine staff to Sofia, Bulgaria, where we opened a new Launcher Europe office. We also invited their immediate family to join them in this move and funded their relocation expenses. We continue to encourage and support five of the support staff and one engineer who decided to remain in Ukraine.

Our Launcher Ukraine team, now based at our European office in Sofia, Bulgaria (2/2/22)

I have personally had the chance to work with Ukrainian engineers since 2005, first for my companies Livestream and Mevo where we built software engineering teams in Ukraine. In 2014, we experienced the first threat to our team members and relocated them to Montenegro as a precaution. I wrote this blog post at the time: https://medium.com/@maxhaot/a-wish-for-ukraine-in-2015-5635b21ff305

When I started Launcher in 2017, with my understanding of the historical aerospace and propulsion talent of Ukraine, combined with experiencing firsthand the quality of their character and engineering skill in the Mevo and Livestream teams, it was clear that creating partnerships in Ukraine to import their design and skill to the U.S., in compliance with U.S. export control (ITAR) requirements, would be a key differentiator in Launcher’s strategy to achieve unmatched high-performance propulsion standards. It is also beneficial to the United States propulsion technology base to increase our nation’s capability in oxidizer-rich staged combustion liquid rocket engines by importing key engineering talent and designs.

As part of this strategy, we also hired our Chief Engineer in Ukraine, Igor Nikishchenko (Blog post announcement). Igor has 30+ years in oxidizer-rich staged combustion engines development and has been US-based since 2018 with a Permanent Resident Status.

For the world’s highest performance closed-cycle rocket engine turbopump designs, we licensed Soviet heritage designs from Yuzhnoye in Ukraine (RD-8 Engine). Our development program no longer has dependencies on deliverables from Yuzhnoye in Ukraine since the royalty-free designs have all been received and the pump is now 3D printed at our HQ in the U.S. and has been successfully tested at NASA Stennis Space Center.

Launcher is currently and has been majority U.S.-owned, with no investment ties to Ukraine or Russia.

Our Orbiter and Light product development continue to meet the schedule expectations of our customers and suppliers.

Quelle: LAUNCHER

+++

BIDEN IMPOSES MORE SANCTIONS ON RUSSIA, BUT NO APPARENT IMPACT ON ISS

President Biden and U.S. allies announced new sanctions today against Russia following its invasion of Ukraine. Among them are further export controls, but NASA says they will not affect U.S.-Russian civil space cooperation. That includes operations of the International Space Station.

In a televised address to the nation this afternoon, Biden laid out “strong sanctions” that will impose “severe costs on the Russian economy” in concert with allies around the world.

Without getting into specifics, he said the sanctions will “strike a blow to their ability to continue to modernize their military. It’ll degrade their aerospace industry, including their space program.”

An associated fact sheet issued by the Department of Commerce said the sanctions include a stringent licensing review policy that will require case-by-case reviews for export applications related to government space cooperation.

Under the stringent licensing review policy being implemented, applications for the export, reexport, or transfer (in-country) of items that require a license for Russia will be reviewed, with certain limited exceptions, under a policy of denial. The categories reviewed on a case-by-case basis are applications related to safety of flight, maritime safety, humanitarian needs, government space cooperation, civil telecommunications infrastructure, government-to-government activities, and to support limited operations of partner country companies in Russia.

“Only certain sections” of seven license exceptions are available for exports to Russia, one of which is “AVS (Aircraft, Vessels, Spacecraft), for aircraft flying into and out of Russia.”

NASA said in a statement this evening that the sanctions will still allow U.S.-Russian civil space cooperation to continue.

NASA continues working with all our international partners, including the State Space Corporation Roscosmos, for the ongoing safe operations of the International Space Station. The new export control measures will continue to allow U.S.-Russia civil space cooperation. No changes are planned to the agency’s support for ongoing in orbit and ground station operations. — NASA

Nonetheless, Biden’s speech triggered a Twitter tirade by Dmitry Rogozin (@Rogozin), Director General of Roscosmos, Russia’s equivalent of NASA. Among other things, he caustically asked if the United States wants to operate the International Space Station by itself and then who will save it from reentering uncontrollably over the United States, Europe, India or China, claiming its orbit does not take it over Russia “so all the risks are yours, are you ready for them?” Except for the final tweet, they are in Russian and translated here by Google Translate.

“SANCTIONS OF ALZ-GEIMER [Alzheimer]

Biden said the new sanctions would affect the Russian space program. OK. It remains to find out the details:

1. Do you want to block our access to radiation-resistant space microelectronics? So you already did it quite officially in 2014.”

“As you noticed, we, nevertheless, continue to make our own spacecraft. And we will do them by expanding the production of the necessary components and devices at home.

2. Do you want to ban all countries from launching their spacecraft on the most reliable Russian rockets in the world?’

“This is how you already do it by limiting exchanges between our cosmonaut and astronaut training centers. Or do you want to manage the ISS yourself? Maybe President Biden is off topic, so explain to him that the correction of the station’s orbit, its avoidance of dangerous rendezvous with space ..”

“garbage, with which your talented businessmen have polluted the near-Earth orbit, is produced exclusively by the engines of the Russian Progress MS cargo ships. If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit and fall into the United States or…’

“Europe? There is also the option of dropping a 500-ton structure to India and China. Do you want to threaten them with such a prospect? The ISS does not fly over Russia, so all the risks are yours. Are you ready for them?

Gentlemen, when planning sanctions, check those who generate them for illness”

“Alzheimer’s. Just in case. To prevent your sanctions from falling on your head. And not only in a figurative sense.

Therefore, for the time being, as a partner, I suggest that you do not behave like an irresponsible gamer, disavow the statement about “Alzheimer’s sanctions”. Friendly advice”

Rogozin was Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister in charge of defense and aerospace in 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea and is under U.S. and European sanctions himself because of it. He is known for his vituperative personality, sometimes expressed on Twitter, but NASA Administrators including Bill Nelson have found a way to work with him constructively.

His comments about the possibilty of ISS reentering over the United States, Europe, India or China refers to the fact that Russia’s space station module Zvezda and its Progress MS cargo spacecraft are used to correct the space station’s altitude, which must be raised periodically to compensate for atmospheric drag, and Progress spacecraft will be used to deorbit the ISS over an uninhabited region of the Pacific Ocean at the end of its life. The other ISS partners — the United States, Canada, Japan, and 11 European countries — currently do not have spacecraft that can perform that function, although the recently launched Northrop Grumman Cygnus NG-17 spacecraft will perform an orbit-correction maneuver for the first time operationally.

The ISS orbit takes it over all parts of the Earth between 51.6 degrees North and 51.6 degrees South latitude. Most, but not all, of Russia is above that latitude.

The complaint about needing to maneuver ISS to avoid “garbage with which your talented businessmen have polluted the near-Earth orbit” appears to be a reference to SpaceX’s hundreds of Starlink communications satellites that are part of the population of objects in low Earth orbit that other space objects, like ISS, must avoid.

The most recent need to maneuver ISS out of harm’s way was in November 2021 when debris from a Russian antisatellite test threatened the facility and the seven crew members had to shelter in place. The crew is composed of two Russians, four Americans, and one German representing the European Space Agency.

The ISS is composed of a Russian segment and a U.S. segment that includes modules and hardware from Europe, Canada, and Japan. The segments are co-dependent and it is difficult to imagine how it could function as a research facility if the partnership ended.

During a George Washington University seminar yesterday, the Director of the U.S. State Department’s Office of Space Policy, Valda Vikmanis-Keller, also conveyed that ISS cooperation is continuing uninterrupted despite Russia’s hostile actions towards Ukraine. Her colleague, Eric Desautels, who heads the Office of Emerging Security Challenges & Defense Policy, added however that the United States is focused on using sanctions and export controls to slow and delay Russian military space systems by ensuring they do not get parts from the U.S. or its allies.

Quelle: SpacePolicyOnline

----

Update: 26.02.2022

.

Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Strains International Space Station Partnership

Life onboard the ISS goes on in the wake of Russia’s attack against Ukraine, even as the space project faces an uncertain future

When Russia launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine on Thursday, the whole world was watching. But another, much smaller audience was watching, too: the seven crew members onboard the International Space Station (ISS), orbiting hundreds of kilometers above the chaos below.

Across more than two decades of continuous operations, the ISS has been a steady beacon of hope for peaceful international collaboration. The massive space habitat is the product of a remarkable partnership among five space agencies (including NASA and Russia’s national space agency Roscosmos) representing 15 participating countries. Over the years, scientific study and international friendships have flourished onboard the ISS, prompting some to petition for the project to receive a Nobel Peace Prize.

But some fear Russia’s latest attack could throw that cooperation into jeopardy. In times of geopolitical upheaval on Earth, what happens to the ISS?

According to former ISS astronauts, nationality usually takes a back seat to the more practical matters of living and working in space. “During training, you spend a lot of time together, and so you form these deep friendships,” says Leroy Chiao, who flew on the 10th expedition to the ISS in 2004.

Rick Mastracchio, a retired NASA engineer who flew on the 38th and 39th expeditions to the ISS, echoes that sentiment. “You’re there to do a very specific job, and you’re well trained,” he says. Regardless of one’s homeland or political views, “you need to get along because you’re [part of] a team.”

Chiao says that the time he spent with his cosmonaut colleagues gave him a measure of insight into the Russian perspective on geopolitics. From Russia’s viewpoint, the prospect of Ukraine joining NATO could seems like a serious threat to national security. How would the U.S. have reacted, he wonders, if Mexico and Canada had signed the Warsaw Pact before the fall of the Soviet Union? “That would make us pretty edgy, too. So, I understand where Russia’s coming from,” he says, even though he firmly disagrees with the nation’s invasion of Ukraine.

Tensions between Russia and the U.S. also ran unexpectedly high when Mastracchio was onboard the ISS. In March 2014, not long into his orbital sojourn, Russia annexed Crimea in a political move that the U.S. condemned as a “violation of international law.”

“I won’t say it affected the atmosphere, but there was some discussion,” Mastracchio says. He mentions what he recalls as the distress of one of his Russian crewmates in particular, who was purportedly fearful for his family in a nearby region of Ukraine. For Mastracchio, the memory serves as a reminder that no culture is a political monolith. “You’re representing your country from the terms of the space agencies, but you’re not representing the political aspect of it,” he says. “It’s somewhat uncomfortable when your homeland does something that maybe you’re not proud of.”

So far, the U.S. and its NATO allies have pursued a policy of retaliatory sanctions targeting Russia’s economy and political leadership. Outlining the policy during a White House address, President Joe Biden noted that the sanctions will “degrade [Russia’s] aerospace industry, including their space program.”

How exactly this may affect life on the ISS remains unclear. The seven crew members currently onboard the habitat are four NASA astronauts, one German astronaut from the European Space Agency (ESA) and two Russian cosmonauts. Whatever their personal feelings, presumably the crew will continue normal operations in a “business as usual” approach. At least, that is the plan according to NASA.

“NASA continues working with all our international partners, including the State Space Corporation Roscosmos, for the ongoing safe operations of the International Space Station,” the agency wrote in an e-mailed statement. “The new export control measures will continue to allow U.S.-Russia civil space cooperation.”

Roscosmos did not respond to a request for comment. But in a series of tweets on Thursday afternoon, Roscosmos’s director general Dmitry Rogozin mocked the sanctions as foolhardy, adding that “if [the U.S.] blocks cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled descent out of orbit and a fall on the United States or Europe?” Despite its threatening implications, Rogozin’s statement is, in some respects, reflective of simple facts: Russia’s Progress resupply spacecraft are currently responsible for periodically boosting the space station’s altitude, which decreases over time because of atmospheric drag. (A U.S.-built Cygnus cargo spacecraft presently docked at the station is scheduled to perform a test boost in April to demonstrate an independent capability to maintain the ISS’s altitude.)

Such comments are not terribly out of character for Rogozin, a Putin appointee. “He’s a bit of, you know, a personality,” says Asif Siddiqi, a historian at Fordham University, who specializes in Russian space activities.

When the U.S. enacted earlier rounds of sanctions after the Crimean annexation, Rogozin notoriously responded by suggesting that American astronauts could find their way to the ISS “with a trampoline.” (At the time, the U.S. was wholly dependent on sending crews to the ISS via launches of the Russian Soyuz spacecraft. Now SpaceX rockets and modules serve as U.S. crew transports, and Boeing is set to soon provide an additional domestic launch option.) Rogozin again raised hackles last year with statements implying that in 2018 NASA astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor drilled a tiny hole in a Soyuz vessel for purposes of sabotage. In an article by the Russian state-owned news agency TASS last year, a Russian space official again raised hackles with accusations that NASA astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor drilled a tiny hole in a Soyuz vessel so that she could return to Earth early. NASA has said it does not consider these allegations credible and that it stands by Auñón-Chancellor.

Although these periods of tension have strained administrative relations between Roscosmos and NASA in the past, they have never truly disrupted life on the ISS. During the height of the Crimean conflict, for example, a leaked internal memo instructed NASA employees to cease communications with their Russian colleagues. “However, there’s a little clause in that thing that says actual ISS operations will continue just as before,” Siddiqi says. He suspects a similar memo may be making the rounds now.

Even if a major ISS partner does decide to withdraw from the project, the transition may take months or even years to fully disentangle. “It’s not a simple off switch,” Siddiqi says. But unless the current political situation changes course, he does not see a future for U.S. and Russian collaboration in space beyond the ISS’s decommissioning, currently planned for 2031. NASA is already looking ahead to its ambitious Artemis program, which will partner with ESA, Japan’s space agency and the Canadian Space Agency to build an orbiting lunar outpost to support astronauts’ long-term return to the moon’s surface. Meanwhile Roscosmos has pledged to join forces with China in order to build a moon base of their own. The international schism in spaceflight seems set to grow—with the cooperation epitomized by the ISS only diminishing.

“It’s clear that this is a relationship that will not continue past a certain point,” Siddiqi says. “I can’t see it recovering from this.”

Quelle: SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN