17.12.2021

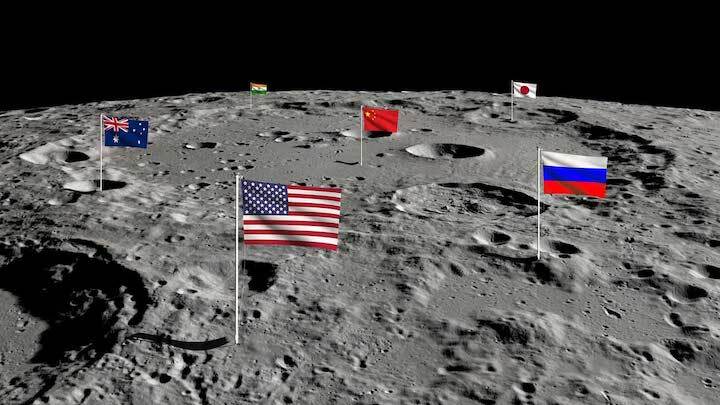

Australia is sending mining robots to the Moon – but they may have to navigate a legal and diplomatic minefield once they get there. While international agreements state that space should be the common heritage of humankind, in practice countries and corporations are jockeying to control lunar resources.

Back in October, the Australian Space Agency (ASA) announced plans to build a rover which will search for and collect samples of water and regolith for NASA – it should be on the lunar surface in 2026. A separate commercial project involving Australian businesses and universities hopes to start searching for water there in mid-2024.

These projects barely raise a blip in the scramble to return to the Moon’s surface. But they will fly straight into a potential diplomatic storm. Where will they land? Where will they go? What happens if someone else is already there?

“Under international law, nobody can go up there and claim territory on the Moon,” says space law expert Professor Melissa de Zwart.

But international law does allow for scientific endeavours that benefit “all humankind”.

“What does that really mean?” Professor de Zwart asks.

With the scramble to exploit lunar resources to build bases for slingshot missions to Mars, we’re about to find that out.

In June, Beijing and Moscow announced plans to start a survey of the lunar surface for the most promising locations for their joint International Lunar Research Station. That site will be chosen in 2025. Construction is scheduled to begin a year later, in 2026.

NASA hopes to have already put its line in the Moon sand (otherwise known as regolith). The Artemis Plan, an international project led by the United States, hopes to put astronauts back on the Lunar surface by 2025.

And Australia’s tiny mining rovers will be rolling about amid it all.

Regolith rumble

The Moon is rapidly becoming humanity’s interplanetary roadhouse. It has water – which is immensely useful. Not only will astronauts be able to drink it, but spacefarers can also use it in various industrial processes, including being broken down into hydrogen and oxygen for fuel.

It’s also heavy, making it both difficult and expensive to boost off the surface of the Earth.

There also are rare-earth minerals scattered amongst the regolith, such as neodymium and lanthanum, both used in modern electronics. There’s also helium-3, a potential source of “clean” nuclear energy (it produces no radioactive waste). So any serious space program will want a piece of the Moon.

And that’s the problem.

Any serious space program will want a piece of the Moon.

The UN General Assembly established the Outer Space Treaty in 1967. Space activities, it states, must be “carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries”. Space should not be weaponised, so the treaty banned nuclear weapons and off-planet military installations. And space should not belong to anyone – all claims of sovereignty are invalid.

Those activities should also benefit all humanity. So it required signatories to take “appropriate” consultations before engaging in acts that could “cause potentially harmful interference” with other space projects and to act with “due regard” for other users.

Australia was one of its 109 signatories. Those provisions sought to map out a common future in space. But the detail was scanty. And what there is will soon be put to the test.

Lunar loopholes

The United States, China and the former Soviet Union refused to ratify the Moon Agreement of 1979, which sought to prevent commercial exploitation of space resources.

Australia, however, was one of 18 nations that did.

Canberra has justified the participation of the ASA in NASA’s regolith mining project under the Space Treaty’s “scientific purposes” exemption.

“Australia’s official position is that we are not in breach of the Moon Agreement and that we can be a member of the Artemis Accords as they are an agency-to-agency agreement,” says Melissa de Zwart. “And under the scope of the agreement, countries can participate to the extent that their domestic laws will enable them to do so.”

But there are potential hurdles.

The Moon Agreement reiterates that the Moon is part of the “common heritage of mankind”. That implies an equal distribution of knowledge and economic returns across the planet. But NASA is not permitted to share any of its knowledge with China.

Now, several nations have taken the first tentative steps towards defining outer space “territory”.

Another clause declares that, when natural resource exploitation is “about to become feasible”, an appropriate international authority must be established to manage such activities.

Australia is about to prove that mining the Moon is feasible, but no significant effort has been made to establish such an overseeing authority.

And then there’s the question: who do bits of the Moon belong to?

The US leads a group of nations that argues that there can be ownership over lunar resources – once they’ve been dug up.

“The analogy is that it’s like taking fish from the sea,” says Professor de Zwart. “Doing so doesn’t mean that you’re asserting sovereignty over the open waters.”

Now, several nations have taken the first tentative steps towards defining outer space “territory”.

The Artemis Accords, which Australia signed up to last year, is contemplating the establishment of “safety zones” in space.

“So again, not asserting sovereignty,” says de Zwart. “But basically, it would say we may be doing an activity here that could be dangerous to you or that could be put at risk by your presence. So it’s starting to look like an Exclusion Zone, the no-fly areas we have here on Earth.”

Staking a claim

The Moon may seem big, but its resources are patchy. The most easily accessible deposits of water ice are believed to exist in Moon craters that provide permanent shade. There aren’t all that many of these. And the best candidates are mostly grouped on the lunar poles – especially in the south.

And that makes them a desirable asset to secure.

So what happens if Chinese, Russian, Indian, Japanese and Israeli rovers all end up in the same crater as the Australian one? Or if SpaceX or Blue Origin stage a corporate takeover?

“You can’t do anything about it,” Professor de Zwart says. “The Moon is an international commons. Everyone can go there. The only thing that you can do is complain that this is potentially unsafe.”

The ASA’s Moon mining rover project will demonstrate its ability to dig into the regolith and assemble it into piles. It’s a proof-of-concept mission. The mounds of material will stay there.

Does it still belong to NASA, or Australia? Or is the extracted soil free for others to claim?

“The Moon is an international commons.”

Melissa de Zwart, Flinders University

“As soon as you start putting up flags or flares or flashing lights, it starts looking like a demarcation or a border or a boundary – whatever we want to call it,” says Professor de Zwart.

And that’s not allowed under the Outer Space Treaty.

It may be eminently practical. But what such lunar “keep out” signs actually mean is yet to be determined.

The idea wouldn’t only apply to the surface of the Moon. It would also establish “buffers” around commercially and strategically sensitive satellites and space stations.

And while the “safety zone” concept reiterates the importance of freedom of navigation, it emphasises the need for openness, communication and respectful distances.

That’s the problem. The United States has largely been transparent about its lunar intentions and is building an international coalition as part of the process.

“But China and Russia are setting up a base on the Moon as well,” de Zwart notes. “And they’re not telling us anything about what they’re going to do or how they’re going to go about it.”

Keep off the H30?

The second Australian-involved lunar project is a private operation. The University of Technology Sydney is teaming with companies in Australia and Canada to build a water-hunting rover to be launched in 2024 by the Japanese ispace Hakuto lander.

And then there are the big corporate Moon projects, such as those of Blue Origin and SpaceX.

But some privately operated Moon missions have been controversial.

“You will get a private operator who will just go to the Moon and do whatever they want,” warns Professor de Zwart.

Israel’s privately funded SpaceIL spilled tiny but hardy tardigrades over the lunar surface after its landing went wrong in 2019.

Will lunar resource exploitation become a matter of “winner takes all”?

“That guy basically said, ‘What’s international space law anyway? You can’t tell me what to do’.”

Will lunar resource exploitation become a matter of “winner takes all”?

“Under space law, all activities are attributable to the nation-state,” says de Zwart. “If an Australian company does something in space, the Australian government is liable under international law for that activity. That’s why we have strict licensing schemes.”

Soon all these treaties, agreements and principles could end up in an international court of arbitration. And even its rulings – as the Philippines recently found out when China’s claim to the Spratly Islands was rejected – aren’t enforceable.

“I think people want to avoid those mistakes of the past,” says de Zwart. “But how to balance those principles with the practicalities is going to be a real challenge, especially if we really want space to be the common heritage of humankind.”

Quelle: COSMOS