24.09.2021

NASA completes swing arm test on SLS launch platform

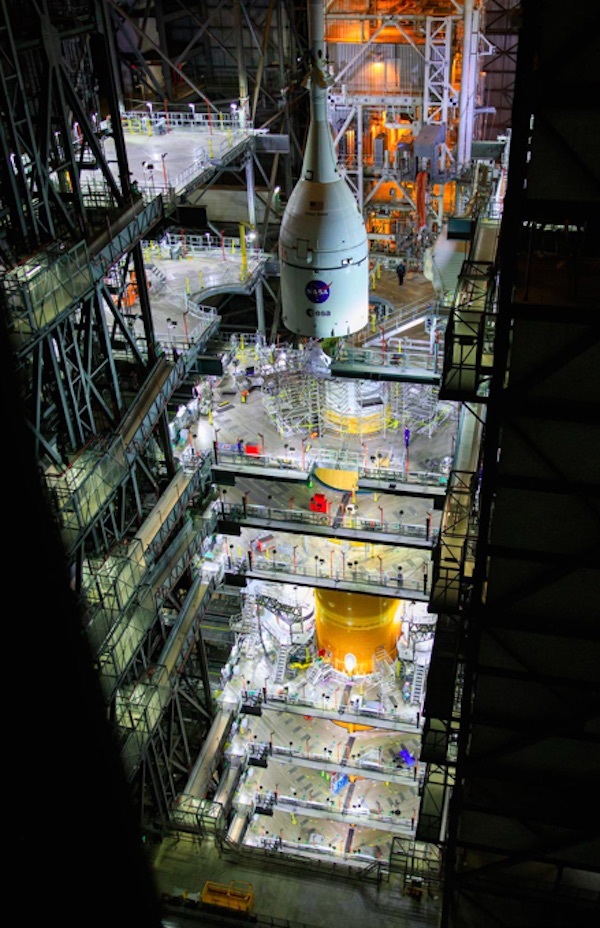

The swing arms on the mobile launch tower for NASA’s Space Launch System released and retracted Sunday night inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center, another key test on the march toward liftoff of the Artemis 1 moon mission.

The Umbilical Release and Retract Test, or URRT, validated the way connections between the Space Launch System and its mobile launch tower will rotate or drop away at ignition and liftoff.

The swing arms and umbilicals provide power, communications, coolant, and propellant to the Space Launch System and the Orion spacecraft on the launch pad, according to NASA.

The umbilicals detached simultaneously from the nearly fully-assembled Space Launch System moon rocket in the VAB high bay, just as they will during liftoff from pad 39B at Kennedy to begin the Artemis 1 mission.

Artemis 1 is the first test flight of NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to return astronauts to the moon in the 2020s. The first test flight of NASA’s new Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket will send an unpiloted Orion crew capsule into lunar orbit for a demonstration mission lasting several weeks. The Orion spacecraft will return to Earth for a splashdown and recovery in the Pacific Ocean.

Future Artemis missions using the SLS will launch four-person teams of astronauts to the moon aboard Orion spaceships.

The Umbilical Release and Retract Test over the weekend verified previous testing that involved detachment of individual umbilicals from simulated SLS interfaces.

“Previous testing at the Launch Equipment Test Facility and in the VAB refined our designs and processes and validated the subsystems individually, and for Artemis 1, we wanted to prove our new systems would work together to support launch,” said Jerry Daun, arms and umbilical systems operations manager at Jabobs, NASA’s ground systems contractor at Kennedy.

“This test is important because the next time these ground umbilical systems are used will be the day of the Artemis 1 launch,” said Scott Cieslak, umbilical operations and testing technical lead, in a NASA statement.

Unlike the moving launch tables used by the space shuttle, the SLS mobile launcher includes a gigantic skyscraper-like structure on the platform itself. The 380-foot-tall (115-meter) Mobile Launcher features a metal tower atop a two-story base with six swing arms that will retract away from the rocket before launch.

In the shuttle era, pads 39A and 39B had fixed umbilical towers to provide astronauts, ground crews and swing arms access to the vehicle. The Apollo program’s Saturn 5 moon rocket used a similar pad setup as the SLS, but the Saturn 5’s mobile tower had nine swing arms.

The SLS tower and platform contain nearly 1,000 pieces of ground support equipment, routing power, data, water, propellants, air conditioning and other commodities to the launch vehicle and Orion crew capsule.

During the retract test Sunday, six swing arms and umbilicals simultaneously released from the Space Launch System.

At the top of the rocket, the Orion Service Module Umbilical detached from a mass simulator stacked on top of the rocket to mimic the weight of the Orion spacecraft, which will be stacked later.

Below the Orion mass simulator, the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage Umbilical released and swung away from the rocket. Near the top of the SLS first stage, the Core Stage Forward Skirt Umbilical and the Vehicle Stabilizer System arms detached as they will during launch.

The Core Stage Inter-Tank Umbilical, located between the first stage’s liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen tanks, and the Tail Service Mast Umbilical at the base off the rocket.

Other swing arms, such as the Crew Access Arm to be used by astronauts boarding the Orion capsule, were not part of the retract test. The crew arm moves away from the launcher in the final minutes of the countdown, not at the moment of liftoff.

“It was a great team effort to build, and now test, these critical systems,” said Peter Chitko, arms and umbilicals integration manager. “This test marked an important milestone because each umbilical must release from its connection point at T-0 to ensure the rocket and spacecraft can lift off safely.”

Unlike the moving launch tables used by the space shuttle, the SLS mobile launcher includes a gigantic skyscraper-like structure on the platform itself. The 380-foot-tall (115-meter) Mobile Launcher features a metal tower atop a two-story base with six swing arms that will retract away from the rocket before or during launch.

In the shuttle era, pads 39A and 39B had fixed umbilical towers to provide astronauts, ground crews and swing arms access to the vehicle. The Apollo program’s Saturn 5 moon rocket used a similar pad setup as the SLS, but the Saturn 5’s mobile tower had nine swing arms.

The SLS tower and platform contain nearly 1,000 pieces of ground support equipment, routing power, data, water, propellants, air conditioning and other commodities to the launch vehicle and Orion crew capsule.

The next milestone in Artemis 1 launch preparations will be the Integrated Modal Test, according to Tiffany Fairley, a NASA spokesperson.

Stingers, or shakers, will introduce vibrations to the rocket as it stands on its support posts at the base of the mobile launch platform. Sensors across the rocket and along the mobile launch tower, will measure the resonant response to the vibrations.

The rocket’s twin side-mounted solid-fueled boosters each stand on four vehicle support posts, with the vehicle’s weight holding it on the mobile platform — without the support of hold-down bolts — during stacking, rollout, and the countdown before liftoff.

That will be followed by removal of the Orion mass simulator and the Orion Stage Adapter test article. Those will be replaced by the flight-ready stage adapter and the real Orion spacecraft, which has been fueled with in-space maneuvering propellant and mated with its launch abort system at Kennedy.

Technicians recently completed installation of ogive fairings over the top of the Orion spacecraft, providing the aerodynamic shield that will cover the capsule during launch.

After additional tests to verify the mechanical and electrical connections between the Orion spacecraft and the SLS rocket, NASA will be ready to roll the fully-assembled launcher to pad 39B atop one of the agency’s Apollo-era crawler transporters.

The rocket will spend about a week on the pad before NASA’s launch team runs through a simulated countdown, culminating in the loading of super-hold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen aboard the launch vehicle.

Assuming that test, known as a wet dress rehearsal, is a success, teams will drain the propellant, safe the rocket, and return the Space Launch System to the Vehicle Assembly Building for final closeouts.

The time-sensitive work inside the VAB after the wet dress rehearsal will include the installation of pyrotechnic ordnance for the rocket’s separation systems and range safety destruct mechanism, which would terminate the flight if the rocket flew off course after liftoff.

Then the rocket will roll back out to pad 39B for another week of preparations ahead of the first launch attempt.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said Tuesday that the Artemis 1 mission could launch at the end of this year or early next year. But NASA officials privately say there is little chance of launch Artemis 1 by the end of December.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 3.10.2021

.

First SLS launch likely to slip to 2022

WASHINGTON — A top NASA official says the agency will soon set a target launch date for the first Space Launch System mission, but that it’s “more than likely” it will slip into early 2022.

Speaking at a Maryland Space Business Roundtable webinar Sept. 30, NASA Associate Administrator Bob Cabana said a firm date for the launch of the Artemis 1 mission hadn’t been set, but suggested it was unlikely to take place before the end of this year.

“I’ll get you a firm date on that hopefully after next week. We’ll set an initial date after the team comes and briefs us on where we are,” he said. “We’ll be flying this Artemis 1 mission hopefully, more than likely, early next year.”

NASA officials have been holding out hope that Artemis 1 could still launch before the end of the year, although they were increasingly hedging their bets. “Artemis 1 will be at the end of this year or the first part of next year,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a call with reporters Sept. 21.

Cabana said workers just completed the night before “modal testing” of the SLS, where the vehicle is subjected to vibrations to determine its natural frequencies. The next milestone is the installation of the Orion spacecraft, taking the place of a mass simulator currently on top of the rocket. He said the Orion spacecraft will be moved to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at the Kennedy Space Center Oct. 13 to be integrated onto the SLS.

Once in place, the entire stack will be rolled out to Launch Complex 39B for a wet dress rehearsal, where the core stage is filled with liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen in a practice countdown that stops just before ignition of the stage’s four RS-25 engines. After that, the rocket will roll back to the VAB for any final work and reviews before going back to the pad for launch.

Asked later in the presentation to give his best guess for both the Artemis 1 launch date as well as future Artemis missions, he declined, citing the upcoming briefing. “Next week, Jim Free and Kathy [Lueders] are coming to brief me and the rest of the team up here on all of the work they were doing at Kennedy this week,” he said. “Hopefully, we’ll have some realistic dates for where we’re going to hit these missions as we go forward. So stand by.”

NASA named Free its new associate administrator for exploration systems development Sept. 21, part of a restructuring that split the former Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate (HEOMD) into two organizations. Lueders, who previously was in charge of HEOMD, is now associate administrator for space operations, responsible for the International Space Station and related programs.

Cabana endorsed the reorganization because it offered a “more focused look” on exploration programs in particular. “He’s just a great engineer and an outstanding program manager,” he said of Free, who returned to the agency from the private sector to lead the new exploration directorate. “It’s going to be his focus to deliver the systems we need to execute Artemis and a sustainable return to the moon, and then to continue to move us on to Mars.”

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 8.10.2021

.

NASA's SLS passes key review for Artemis I ,ission

NASA has completed the design certification review (DCR) for the Space Launch System Program (SLS) rocket ahead of the Artemis I mission to send the Orion spacecraft to the Moon.

NASA has completed the design certification review (DCR) for the Space Launch System Program (SLS) rocket ahead of the Artemis I mission to send the Orion spacecraft to the Moon. The review examined all the SLS systems, all test data, inspection reports, and analyses that support verification, to ensure every aspect of the rocket is technically mature and meets the requirements for SLS's first flight on Artemis I.

"With this review, the NASA has given its final stamp of approval to the entire, integrated rocket design and completed the final formal milestone to pass before we move forward to the SLS and Artemis I flight readiness reviews," said John Honeycutt, the SLS Program Manager who chaired the DCR board held at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

In addition to the rocket's design, the review certified all reliability and safety analyses, production quality and configuration management systems, and operations manuals across all parts of the rocket including, interfaces with the Orion spacecraft and Exploration Ground Systems (EGS) hardware. With the completion of the SLS DCR, NASA has now certified the SLS and Orion spacecraft designs, as well as the new Launch Control Center at the agency's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, for the mission.

The DCR is part of the formal review system NASA employs as a systematic method for manufacturing, testing, and certifying space hardware for flight. The process starts with defining what the rocket needs to do to achieve missions, such as its performance; these are called systems requirements.

Throughout this process the design of the hardware is refined and validated by many processes: inspection, analysis, modeling, and testing that ranges from single components to major integrated systems.

As the design matures, the team evaluates it during a preliminary design review, then a critical design review, and finally after the hardware is built and tested, the design certification review. The review process culminates with the Artemis I Flight Readiness Review when NASA gives a "go" to proceed with launch.

"We have certified the first NASA super heavy-lift rocket built for human spaceflight in 50 years for missions to the Moon and beyond," said David Beaman, the manager for SLS Systems Engineering and Integration who led the review team. "NASA's mature processes and testing philosophy help us ask the right questions, so we can design and build a rocket that is powerful, safe, and makes the boldest missions possible."

Artemis I will be the first integrated flight test of the SLS and Orion spacecraft. In later Artemis missions, NASA will land the first woman and the first person of color on the surface of the Moon, paving the way for a long-term lunar presence and serving as a steppingstone on the way to Mars.

Quelle: SD

----

Update: 21.10.2021

.

NASA moves Orion spacecraft to the Vehicle Assembly Building

Teams at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center moved the Orion spacecraft for the Artemis 1 moon mission into the Vehicle Assembly Building Tuesday for stacking on top of the Space Launch System.

The 67-foot-tall (20-meter) spacecraft, with its launch abort system tower attached, rolled into the iconic assembly building around 5 a.m. EDT (0900 GMT) Tuesday.

The Orion spacecraft rode a special transporter from the Launch Abort System Facility to the VAB. The 6-mile (10-kilometer) journey from the Kennedy Space Center’s industrial area took more than four hours.

Now inside the VAB, the spacecraft will be lifted by crane atop the SLS heavy-lift rocket later this week, capping off the stacking of the 322-foot-tall (98-meter) launch vehicle for the Artemis 1 mission scheduled to blast off early next year.

A crane will lift the Orion spacecraft out of High Bay 4, where it arrived early Tuesday, and across the width of the cavernous assembly building into High Bay 3, where the SLS is mounted on its mobile launch platform.

Artemis 1 is the first full-up unpiloted test flight of the SLS and Orion vehicles, paving the way for future crew missions to the moon.

The Orion spacecraft for the Artemis 1 mission arrived in the Launch Abort System Facility on July 10 after moving from the nearby Multi-Payload Processing Facility, where technicians filled the ship with hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants.

The highly toxic, but storable, propellants will feed the spacecraft’s main engine, a former orbital maneuvering system engine from the space shuttle program. The engine is mounted on the bottom of the spacecraft’s European-built service module, which itself is fixed under the pressurized Orion crew compartment.

With the spacecraft fueled for flight, teams at Kennedy installed Orion’s launch abort system over the summer. The final closeout work in recent weeks involved the installation of ogive panels around the circumference of the 16.5-foot (5-meter) diameter spacecraft.

The four ogive panels serve as an aerodynamic shield over the Orion crew capsule during the first few minutes of flight on top of the Space Launch System rocket.

The fully fueled Orion spacecraft weighs about 74,000 pounds (33,500 kilograms), including the launch abort system, which was mounted on the capsule with its pre-packed solid propellant already loaded. The abort motor will not be active for the Artemis 1 mission, but the escape tower’s jettison motor will fire to propel the structure away from the Orion spacecraft after liftoff.

The Orion crew module was built by Lockheed Martin in a clean room facility at Kennedy Space Center, and the service module was manufactured by Airbus in Bremen, Germany. Northrop Grumman is prime contractor for the launch abort system.

Although no astronauts will fly on the Artemis 1 mission, NASA will fly an instrumented mannequin in the commander’s seat of the Orion spacecraft. The mannequin will be fitted with two radiation detectors, and will wear a spacesuit similar to the ones astronauts will use on future Artemis missions.

The seat will be equipped with sensors to measure vibration and acceleration throughout the flight.

The Artemis 1 mission will mark the second flight in space of an Orion capsule, following a test mission in 2014 in Earth orbit. The mission, called Exploration Flight Test 1, did not include an active service module. NASA and Lockheed Martin began developing the Orion spacecraft in 2006 under the Constellation moon program, which was canceled in 2010.

The Orion spacecraft survived the cancellation of the Constellation program. Artemis 1 will be the first flight of NASA’s Space Launch System, a heavy-lift rocket a decade in the making.

The Obama administration and Congress agreed to redirect NASA’s deep space exploration program in 2011 toward an eventual mission to Mars. The change saw the birth of the SLS program.

Under the Trump administration, the exploration program was re-focused on the moon and was renamed Artemis, the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology.

The Artemis 1 mission will send the Orion spacecraft on a voyage to orbit the moon. The flight will last at least three weeks — and possibly as long as six weeks — before the capsule returns to Earth for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

If the mission goes well, NASA plans to launch the next Artemis mission — Artemis 2 — as soon as late 2023 with three NASA astronauts and one Canadian astronaut on-board. That flight will carry the crew around the far side of the moon and back to Earth.

During the swing behind the far side of the moon, the astronauts will reach distances farther than anyone has traveled from Earth, beating a record set on the Apollo 13 mission in 1970.

A third Artemis mission will link up with a SpaceX lunar lander near the moon. Astronauts will ride the SpaceX craft, based on the company’s Starship rocket system, to a landing near the moon’s south pole.

Future Artemis flights will conduct more moon landings, and visit a mini-space station named the Gateway that NASA intends to construct with international partners in lunar orbit.

Orion: Nasa's Moon ship ready to be attached to rocket

Nasa's next-generation spaceship is ready to be attached to a rocket that should send it to the Moon this year or in early 2022.

On Monday, the Orion spacecraft was moved between buildings at Florida's Kennedy Space Center ahead of being lifted on to the powerful Space Launch System (SLS) rocket.

For its upcoming flight, Orion will fly around the Moon without astronauts.

It's part of a US plan to return people to the lunar surface this decade.

This programme is called Artemis - after the sister of Apollo - and could help establish a long-term human presence on Earth's only natural satellite.

The Orion vehicle that will be used on the Artemis-1 mission was transferred to the famous cuboid Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at Kennedy.

It was being housed at another facility on the same site, where engineers had attached the spacecraft's launch abort system, designed to propel Orion and its astronauts away from the rocket if an emergency occurs during a crewed launch.

Orion is the last key element to be lifted on to the 98m (322ft) -tall SLS launcher, which engineers have been assembling in the VAB since December 2020.

The three-week Artemis-1 mission will test the SLS and Orion before astronauts are allowed aboard for Artemis-2, which will loop around the Moon in late 2023.

Artemis-3 will see astronauts land on the lunar surface for the first time since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. Nasa has selected Elon Musk's Starship as the vehicle that will carry humans down from lunar orbit to the surface.

The landing mission is currently scheduled for 2024, though many observers expect that date to slip.

The metal frame for the Orion spacecraft that will be used for that mission also arrived at Kennedy Space Center earlier this month.

The Artemis-3 mission will carry the first woman to walk on the surface, along with the next man. The Artemis programme will also see the first person of colour travel to the Moon.

Quelle: BBC

----

Update: 24.10.2021

.

NASA's SLS mega moon rocket stacked for the first time, launch slips to 2022

Everything is finally coming together for the first launch of NASA's mega moon rocket, now slated for the first half of next year.

Teams at Kennedy Space Center this week put the finishing touches on the Space Launch System rocket with the completion of "stacking," a process that mates hardware from bottom-to-top in the Vehicle Assembly Building. The Orion capsule now secured atop the upper stage pushes SLS' height to 322 feet.

"It's a heck of a sight and it's really nice to see," Mike Bolger, manager of KSC's Exploration Ground Systems, told reporters Friday. "I'm really, really looking forward to the first day when we roll out of the VAB to the launch pad and see it in all its magnificence because it's a heck of a rocket and Orion's a heck of a spacecraft."

SLS and its Orion capsule are the vehicles chosen to take NASA astronauts back to the moon no earlier than 2024, a program known as Artemis. It begins with Artemis I, an uncrewed mission that will see Orion fly around the moon before returning to Earth for splashdown.

The successful stacking sets SLS on track to launch that mission no earlier than Feb. 12, the opening of a roughly two-week window at pad 39B. If teams are ready that day, a 21-minute window opens at 5:56 p.m. ET.

Before launch, however, Bolger cautioned there's still work to be done. Operations include:

- This weekend: Power up the Orion spacecraft

- November: Power up first and second stages separately, then together

- December: End-to-end communications test with the hardware

- December or later: Full countdown sequence test

After those operations comes the most significant test ahead of launch: the stacked rocket will roll out to pad 39B atop a historic crawler-transporter, then undergo a full "wet dress rehearsal." That includes fueling and communicating with the rocket's systems as if it were launch day itself, then draining the tanks and moving back into the VAB.

If all goes well, Artemis I's launch window will open during the evening of Feb. 12. A delay to March would see another window available from the 12th to 27th; in April, launch opportunities would begin on the 8th and close the 23rd.

"If we don't make the February launch period, we're going to be prepared and have the trajectory data and mission plans in place," Bolger said. "The pattern we've got is we're on for roughly two weeks, then we're off for about two weeks."

The on-and-off pattern has to do with the complicated three-body orbits of Earth, the moon, and sun. Artemis I's Orion capsule will fly for at least 26 days during its trek, about a week of which will be in lunar orbit.

If successful, Artemis II will fly a similar configuration, but this time with astronauts in orbit around the moon. Artemis III will finally be the mission with two astronauts – the first woman and a person of color – destined for the lunar surface.

The process is similar to the early Apollo missions, which gradually increased experience and pushed boundaries until Apollo 11's landing in July 1969. Just like plans for Artemis, several Apollo missions flew before NASA gave the all-clear for astronauts to approach the surface.

Though NASA is targeting 2024 for the touchdown, experts and the agency's own inspector general have cautioned delays are likely.

The Artemis program is no stranger to scheduling issues. The SLS rocket is years behind schedule and billions of dollars over budget. Boeing is the prime contractor, but others like Lockheed Martin and Aerojet Rocketdyne (now part of Lockheed) are responsible for the Orion spacecraft and engines, respectively.

Nailing down a precise age for SLS is complicated – its RS-25 main engines, for example, are holdovers from the space shuttle era and the four launching Artemis I are actually previously flown. SLS' side-mounted solid rocket boosters, though upgraded, are sourced from the shuttle program, too.