8.09.2021

Astronomer Michael Brown led the campaign that controversially demoted Pluto in 2006 from the ninth planet of our solar system into just one of its many dwarf planets. Now, he hopes to fill the gap he created with what he predicts will be the discovery of a “Planet Nine” — a planet many times the size of Earth that might orbit the sun far beyond Neptune.

“It was definitely not the intention,” said Brown, a professor of planetary astronomy at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and the author of the memoir “How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming.”

“If I were prescient enough to have had all these ideas ahead of time and then demoted Pluto and found a new Planet Nine, then that would be brilliant — but it really is just a coincidence,” he said.

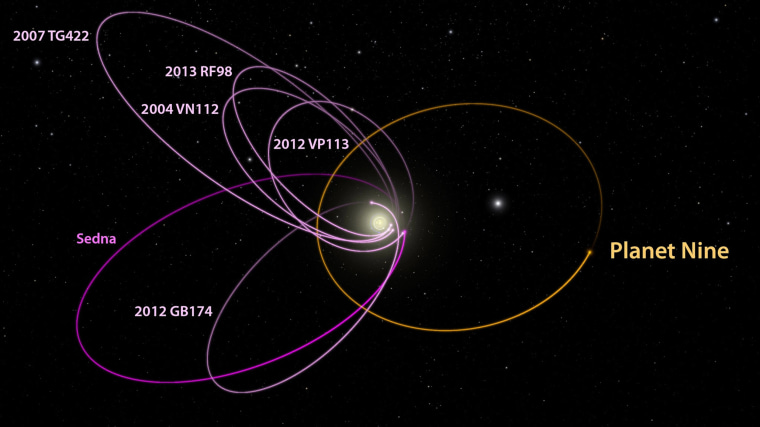

A study published online in August by Brown and his colleague at Caltech, astrophysicist Konstantin Batygin, re-examines the evidence for a proposal they first suggested in 2016: that the hypothetical Planet Nine could explain anomalies seen by astronomers in the outer solar system, especially the unusual clustering of icy asteroids and cometary cores called Kuiper belt objects. The study has been accepted for publication by the Astronomical Journal, according to National Geographic.

Despite years of looking, Planet Nine has never been seen. As a result, some astronomers have suggested it doesn’t exist and the clustering of objects noted by Brown and Batygin is the result of “observation bias” — since fewer than a dozen objects have been seen, their clustering might be a statistical fluke that wouldn’t be seen among the hundreds thought to exist.

For their latest study, however, Brown and Batygin have added several recent observations of objects, and they’ve calculated that the clustering is almost certainly real — in fact, they found there is only a 0.4 percent chance that it’s a fluke.

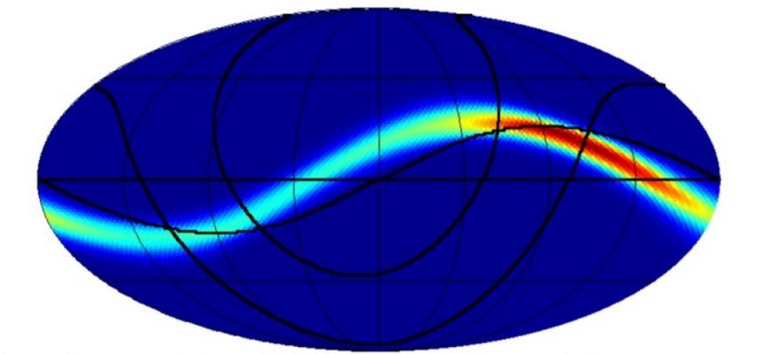

That would suggest Planet Nine is almost certainly there — and the new study includes a "treasure map" of its supposed orbit that tells astronomers the best places in the sky to look for it.

Brown is working with data from several astronomical surveys, hoping to catch the first glimpse of Planet Nine. If that search is not successful, he hopes it might be seen in survey data from a new large telescope at the Vera Rubin Observatory in the mountains of northern Chile, which is scheduled to start full operations in 2023.

One of the results of the new study is that the orbit of Planet Nine is closer to the sun than what the 2016 study proposed, with an elongated orbit only about 380 times the distance between Earth and the sun at its closest, instead of more than 400 times that distance.

The closer orbit would make Planet Nine much brighter and much easier to see, Brown said, although their recalculations suggest it’s also a bit smaller — about six times the mass of Earth, instead of up to 20 times as big.

“By virtue of being closer, even if it’s a little less massive, it’s a good bit brighter than we originally anticipated,” he said. “So I’m excited that this is going to help us find it much more quickly.”

If Planet Nine does exist, it’s probably a very cold gas giant like Neptune, rather than a rocky planet like Earth. It would be smaller, however: Neptune is more than 17 times the mass of Earth. But roughly six to 10 times Earth’s mass is the most common size of gas giants seen by astronomers elsewhere in our galaxy, although there are none — so far — in our solar system, Brown said.

While Planet Nine might have formed at such a great distance from the disk of gas around the early sun, it seems likely it formed about the same distance from the sun as Uranus and Neptune, but it was flung off into the outer reaches of the solar system by the strong gravity of Saturn, he said.

He dismissed the suggestion made by astronomers last year that Planet Nine might actually be a black hole orbiting the sun.

“It was almost a joke when they wrote that paper,” he said. “It’s funny and it’s cute — but there is really zero reason to speculate that it might be a black hole.”

As Brown and his colleagues renew their search for Planet Nine with a better idea of where to look, some other astronomers remain skeptical that it even exists.

Physicist Kevin Napier, a graduate student at the University of Michigan, led a study published earlier this year that suggested the clustering of objects in the Kuiper belt was a statistical illusion.

He said in an email that the extremely small number of orbits of objects used as evidence for the existence of Planet Nine — just 11 are known — is unconvincing.

“There is only just so much statistical power one can draw from a dozen data points,” he said.

That means the existence of Planet Nine can only be conjectured until more observations of the outer solar system are made.

“Maybe we will discover a new planet lurking in the darkness, or maybe our discoveries will cause any evidence for clustering to disappear altogether,” he said. “Until then, we will keep searching the sky for new and interesting rocks, and by doing so pull our understanding of our solar system into clearer focus.”

Quelle: NBC News