19.03.2021

© Roland Bacon, David Mary, ESO et NASA

Although the filaments of gas in which galaxies are born have long been predicted by cosmological models, we have so far had no real images of such objects. Now for the first time, several filaments of the ‘cosmic web’ have been directly observed using the MUSE1 instrument installed on ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. These observations of the early Universe, 1 to 2 billion years after the Big Bang, point to the existence of a multitude of hitherto unsuspected dwarf galaxies. Carried out by an international collaboration led by the Centre de Recherche Astrophysique de Lyon (CNRS/Université Lyon 1/ENS de Lyon), also involving the Lagrange laboratory (CNRS/Université Côte d’Azur/Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur)2, the study is published on 18 March 2021 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The filamentary structure of hydrogen gas in which galaxies form, known as the cosmic web, is one of the major predictions of the model of the Big Bang and of galaxy formation [figure 1]. Until now, all that was known about the web was limited to a few specific regions, particularly in the direction of quasars, whose powerful radiation acts like car headlights, revealing gas clouds along the line of sight. However, these regions are poorly representative of the whole network of filaments where most galaxies, including our own, were born. Direct observation of the faint light emitted by the gas making up the filaments was a holy grail which has now been attained by an international team headed by Roland Bacon, CNRS researcher at the Centre de Recherche Astrophysique de Lyon (CNRS/Université Lyon 1/ENS de Lyon).

© Jeremy Blaizot / projet SPHINX

The team took the bold step of pointing ESO’s Very Large Telescope, equipped with the MUSE instrument coupled to the telescope’s adaptive optics system, at a single region of the sky for over 140 hours. Together, the two instruments form one of the most powerful systems in the world3. The region selected forms part of the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field, which was until now the deepest image of the cosmos ever obtained. However, Hubble has now been surpassed, since 40% of the galaxies discovered by MUSE have no counterpart in the Hubble images.

© Roland Bacon / David Mary

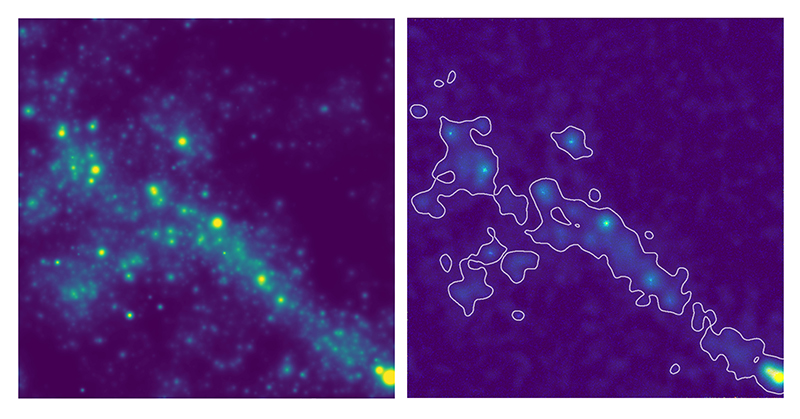

After meticulous planning, it took eight months to carry out this exceptional observing campaign. This was followed by a year of data processing and analysis, which for the first time revealed light from the hydrogen filaments, as well as images of several filaments as they were one to two billion years after the Big Bang, a key period for understanding how galaxies formed from the gas in the cosmic web [figures 2 et 3]. However, the biggest surprise for the team was when simulations showed that the light from the gas came from a hitherto invisible population of billions of dwarf galaxies spawning a host of stars4 [figure 4]. Although these galaxies are too faint to be detected individually with current instruments, their existence will have major consequences for galaxy formation models, with implications that scientists are only just beginning to explore.

© Roland Bacon, David Mary, ESO and NASA

© Thibault Garel and Roland Bacon