28.02.2021

How did NASA’s Martian rover come to land in a crater named after a tiny Balkan village?

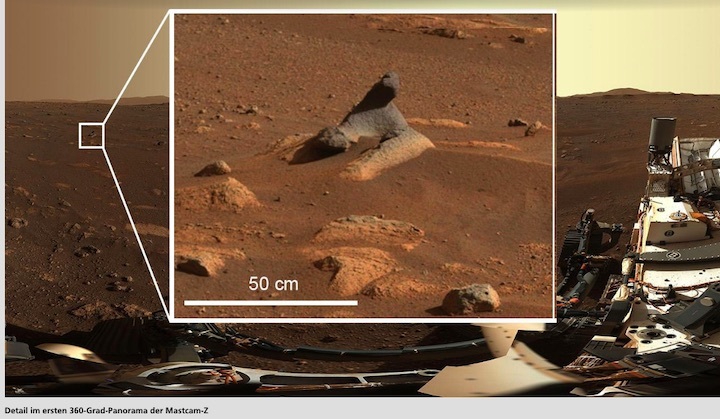

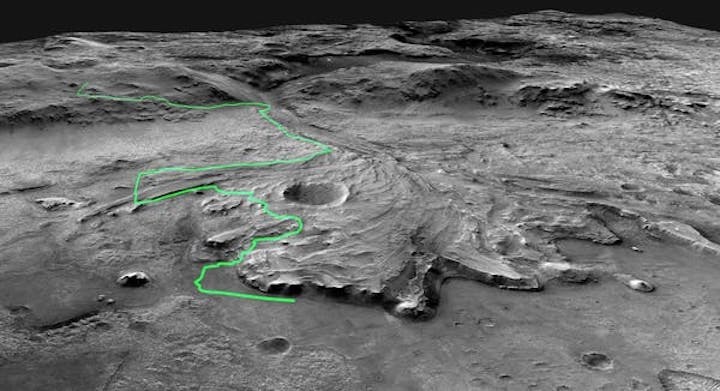

The world was excited by the news last week that NASA’s Perseverance rover had successfully landed in a Martian crater. The rover will now set about collecting samples from what scientists say was an ancient lake fed by a river. The name of this exotic Martian crater is Jezero.

As a South Slavic linguist, I immediately recognised the word. In several former Yugoslav countries, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia, “jezero” (pronounced “yeh-zeh-ro”, with the stress on the first syllable) means lake. Fair enough — but why a Balkan lake on Mars?

The task of providing names for places of interest on Mars falls to the International Astronomical Union (IAU). They apparently named the Martian crater Jezero in 2007, well before earthlings had paid any attention.

I later discovered the name was not, in fact, intended simply as a generic “lake”, but refers to a specific village called Jezero. With a population around 500, it is located in western Republika Srpska, the Serb-dominated part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is very near a river-fed lake called Veliko Plivsko Jezero, or Great Plivsko Lake.

Famous on Mars

According to the Balkan Insight news service, the mayor of Jezero first learned of NASA’s plans in a letter from the US ambassador in Bosnia and Herzegovina, informing her the village and its name were to be honoured by the spacecraft landing in the Jezero crater.

The villagers apparently first dismissed this as fake news. But, to their later amazement, people all over the world have now been learning to pronounce Jezero properly.

The landing was broadcast live at the village’s only school, with the Balkan Insight reporter describing the villagers as “star-struck” and justifiably proud of their connection to the mission.

There was also cautious optimism about the prosperity that might flow from tourists discovering their sleepy hamlet (at least after the pandemic). Famous on Mars, might Jezero be celebrated on Earth as well?

Earthly tensions

The alternative to be avoided, one hopes, is that a minor Balkan conflict breaks out over language and designated names. Every one of the former Yugoslav countries can claim the word “jezero” in their respective dictionaries. And any traveller to the Balkans knows the region is rich with lakes.

But only one village carries this generic word as its name. Was it politically advisable for one village in the Serb-dominated entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina to be singled out? For many, this part of the country is still associated with the nationalism and ethnic cleansing of the Bosnian war in the 1990s.

How would the members of other communities in the country — Bosniaks (the country’s Muslim population) and Croats — respond? Could they support the Serbs of Jezero receiving such positive media coverage?

As my book about the break-up of the Serbo-Croatian languageexplored, language rifts in the Balkans are endemic and have long been both a symptom of ethnic animosity and a cause for inflaming it.

Will people quibble over whether the crater is named for the village or for its nearby lake, or any lake within the region? Or should all who say “jezero” feel proud the word is now in the global lexicon?

Space and time

During the time of Tito’s rule in Yugoslavia, such matters would not have been as contentious, since many people believed the dominant common language of the country was Serbo-Croatian.

Ethno-nationalism was forbidden and people mostly got along. However, since the violent break-up of Yugoslavia, people in the newly independent states now speak separate languages: Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian.

Over the years, speakers of the four languages have slowly drifted apart, but they all agree a lake is called “jezero”. Further complications arise with peoples and governments even further afield. The Slovenes and Czechs also say “jezero”, and the Macedonian and Bulgarian form is the almost identical “ezero”.

Any similarity between the landscape around Jezero in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the crater with the same name on Mars may end with the name. And I doubt the scientists at NASA or the IAU ever considered the potential implications of using a common word shared by so many nations to name an important site on Mars.

But, as we know, words have power. It would be a shame if a distant, silent crater on another planet caused envy and resentment here on Earth. So far, however, the political situation in the Balkans remains almost as calm as that on Mars, and that is cause for hope.

Quelle: The Conversation

----

Update: 1.03.2021

.

Testing Proves Its Worth with Successful Mars Parachute Deployment

Test. Test again. Test again.

Testing spacecraft components prior to flight is vital for a successful mission.

Rarely do you get a do-over with a spacecraft after it launches especially those bound for another planet. You need to do everything possible to get it right the first time.

Three successful sounding rocket missions from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia in 2017 and 2018 to test a supersonic parachute proved their worth with the successful landing of the Perseverance mission on the red plant.

After a 203-day journey traversing 293 million miles, the supersonic parachutes, designed to slow the rover’s descent to the planet’s surface, successfully deployed and inflated leading to the smooth touchdown of Perseverance.

Perseverance Landing: Video from Mars

“This mission required us to design and build a 72-ft parachute that could survive inflating in a Mach 2 wind in about half a second. This is an extraordinary engineering challenge, but one that was absolutely necessary for the mission,” said Ian Clark, the test’s technical lead from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “To ensure they worked at Mars under those harsh conditions, we had to test our parachute designs here at Earth first. Replicating the Martian environment meant that we needed to get our payload half way to the edge of space and going twice the speed of sound. Sounding rockets were critical to our testing and ultimately our landing on Mars.”

The NASA team tested the parachute three times in Mars-relevant conditions, using Black Brant IX sounding rockets. The final test flight exposed the chute to a 67,000-pound (300,000- Newton) load — the highest ever survived by a supersonic parachute and about 85% higher than what the mission's chute was expected to encounter during deployment in Mars' atmosphere.

Testing a Parachute for Mars video

“When the spacecraft successfully touched down last week it was a great feeling of accomplishment for the parachute testing team,” said Giovanni Rosanova, chief of the NASA Sounding Rockets Program Office at Wallops. “Placing the test component in the right conditions with a sounding rocket was challenging and the importance of the tests to the success of the Mars landing was an exciting motivating factor for the team. We are proud to have been a part of this mission.”

Suborbital vehicles – sounding rockets, scientific balloons, and aircraft - are great platforms for developing and testing spacecraft instruments and components. Spacecraft including Terra, Aqua, COBE, CGRO, SPITZER, SWIFT, HST, SOHO, and STEREO, have heritage connected with suborbital vehicle missions.

Rosanova said, “One of the beauties of suborbital vehicles is that an instrument or its components can be flown, improved, and then re-flown. This can be done within a few years, providing the opportunity for scientists to work out the bugs before flying on a spacecraft.”

In the case of the Mars 2020 parachutes, the first flight was a test to see if the right conditions can be achieved during the flight to simulate what the parachutes will encounter descending through the Mars’ atmosphere. The second flight, 6 months later in March 2018, was the first full test of the parachute. The final successful test conducted in September 2018 provided the results needed for the Perseverance parachute team to be confident that the design was ready for the Mars 2020 mission.

NASA is currently developing plans for a Mars Sample Return mission to retrieve the rocks and soil samples collected by Perseverance and return them to Earth. Teams are preparing to test concepts for the Mars Ascent Vehicle that will carry the collected samples from the planet’s surface.

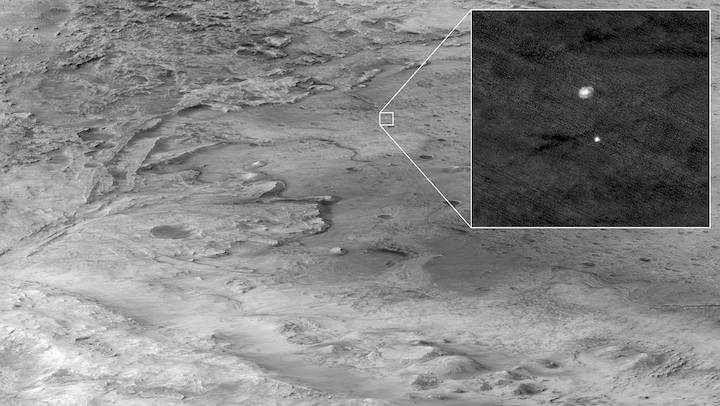

Suborbital vehicles, either a sounding rocket or a scientific balloon, are being examined for testing the ascent vehicle. Wallops personnel are excited to be a part of this next step of exploring the red planet as we go the Moon, Mars, and beyond.Header Image: The descent stage holding NASA’s Perseverance rover can be seen falling through the Martian atmosphere, its parachute trailing behind, in this image taken on Feb. 18, 2021, by the High Resolution Imaging Experiment (HiRISE) camera aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Credit NASA/JPL Cal-Tech

Quelle: NASA

+++

Punktgenaue Marslandung mit Bildern und Tönen am 18. Februar