31.10.2020

Records are there to be broken, it is often said, and generally astronauts who set records—whether for age, number of flights, cumulative time spent in space or Extravehicular Activity (EVA)—desire them to be broken quickly. “If we don’t keep breaking records,” wrote seven-time flyer Jerry Ross in his memoir, Spacewalker, “we’re not progressing.” Yet one record was set over two decades ago and still stands to this day.

John Glenn, hero of Project Mercury and the first American to orbit the Earth, returned from a decades-long career in the U.S. Senate and on 29 October 1998 flew again aboard shuttle Discovery. In doing so, Glenn launched into space at the grand age of 77. Even today, almost four years after Glenn’s death, he retains the accolade for the oldest human ever launched into the heavens.

When Glenn launched aboard STS-95, a nine-day scientific research flight, he was more than a decade older than the next-oldest astronaut on the list and the ostensible reason for flying a septuagenarian was to assess the effect of spaceflight upon the aging process. However, the lack of “repeatability” of the feat and the singular data-point afforded by Glenn’s mission led many critics to regard it as little more than a publicity stunt.

But the astronaut himself, in his autobiography, John Glenn: A Memoir, wrote that it demonstrated to elderly people worldwide that life experiences were by no means off-limits on the basis of age. He recalled bumping into an elderly couple at an airport, who told him that STS-95 had inspired them to pursue their own dream to summit Mount Kilimanjaro.

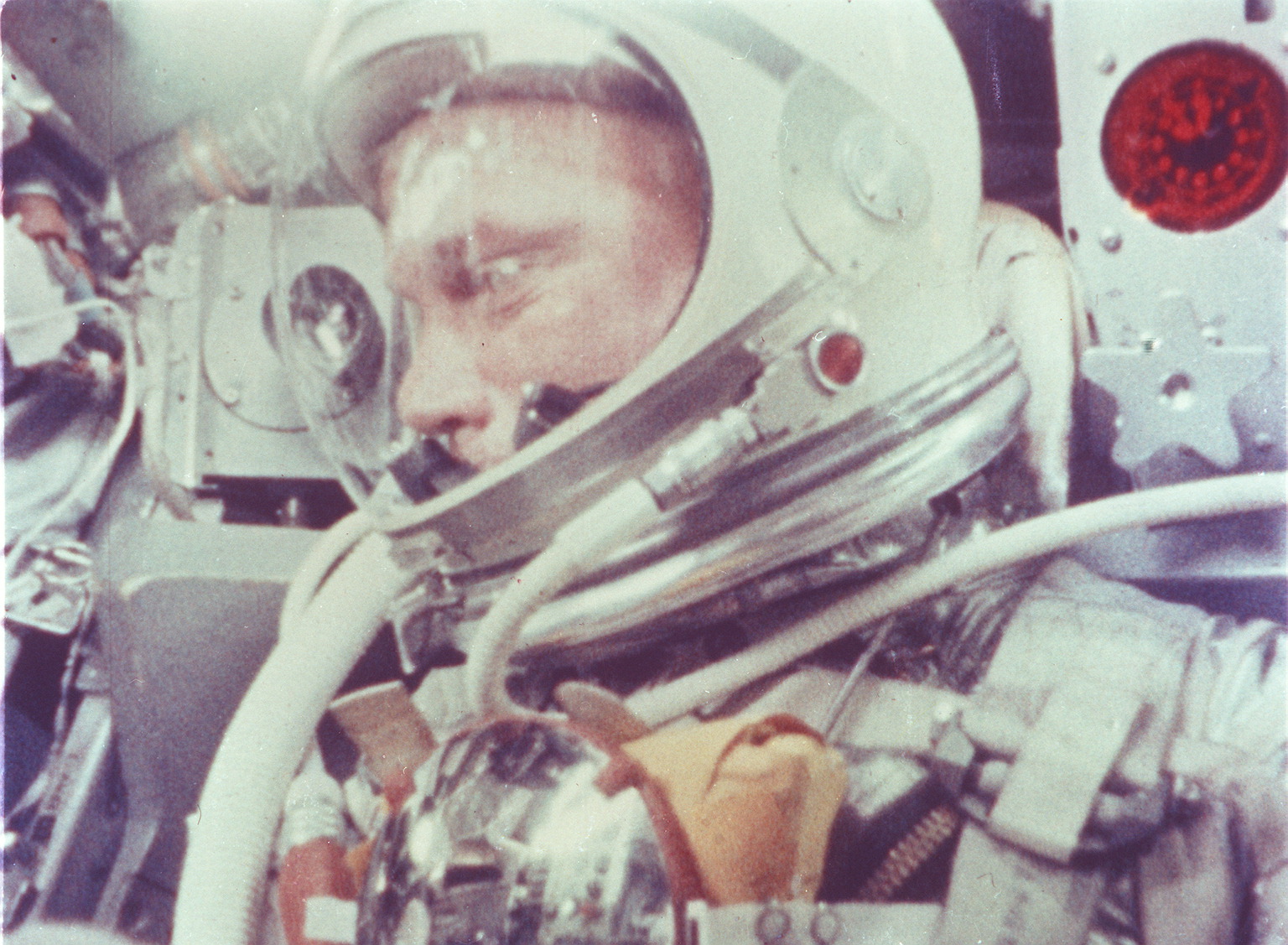

The rumor mill had been rife since summer 1997 that Glenn, then the long-time senior Democratic senator for Ohio, was in the pipeline a Shuttle launch, more than three decades after his Friendship 7 orbital mission.

“In early 1995,” he wrote, “I prepared for debate on [NASA’s] budget by reviewing the latest NASA materials, including Space Physiology and Medicine, a book written by three NASA doctors. As I read, a chart jumped out at me.” The chart described the physical effects upon astronauts in space, including muscular changes, osteoporosis, disturbed sleep patterns, balance disorders, a less responsive immune system, cardiovascular changes, loss of co-ordination, a decline in drug and nutrient absorption and differences in blood distribution patterns.

After several years working on the Special Committee on Aging, Glenn pondered the possibility of an older person venturing into space to evaluate these effects. In his mind, such research carried potentially great implications for future International Space Station (ISS) crews, who would spend many months in orbit.

Late in 1995, he approached NASA Administrator Dan Goldin for the first time with the possibility and was received with warm enthusiasm, but it would appear that Glenn’s support for President Bill Clinton in his effort to secure re-election in 1996 aided his campaign immeasurably.

After discussing the idea with the president, Glenn described a flight with Clinton in Ohio, whilst on the campaign trail. “We were returning to the airport,” Glenn wrote, “when [Clinton] brought the subject up again. He grinned, leaned over and slapped me on the knee. ‘I hope that flight works out for you,’ he said.”

Of course, it was not enough to have the backing of the president. To convince the nation and the world that this was not simply an old senator and U.S. hero getting a joy ride into space required Glenn to ensure that his mission pulled its own weight in terms of its scientific gain. And that “gain” has been repeatedly questioned over the years, with critics and supporters on both sides of the fence.

“My campaign for a shuttle flight had taken me to Dr. John Eisold, the U.S. Navy admiral who was the attending physician for Congress,” wrote Glenn, “and had an office in the Capitol.” At the Bethesda Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Md., he was put through heart exams, liver, kidney and pancreatic scans, a whole-body MRI scan, and a head scan. At the end of the grueling tests, Eisold told Glenn that he saw no physical problem which prevented the former astronaut from flying again.

At a follow-up meeting with Dan Goldin—and carrying his medical results in hand—Glenn reiterated his interest. This time, Goldin took serious notice of his words and gave Glenn two conditions: first, that his mission should be scientifically valuable, and second, that he should be able to pass all of the exams required by active-duty astronauts, many of whom were half his age. In John Glenn: A Memoir, Glenn stressed that his wife, Annie, and grown children were unhappy with the notion of him flying again. (Annie’s initial response was “Over my dead body!”)

However, it was turning inexorably from a dream into a reality. “Back in Washington, on 15 January 1998,” Glenn wrote, “an aide interrupted a meeting with the word that I had a phone call.” It was Goldin. “You’re the most persistent man I’ve ever met,” he said. “You’ve passed all your physicals, the science is good and we’ve called a news conference tomorrow to announce that John Glenn’s going back into space!”

Three weeks after Glenn was announced to join the STS-95 mission, in February 1998 the remainder of the crew was announced. All but one were veterans, and yet all were starstruck by their crewmate. Commander Curt Brown was six years old when Glenn flew his Mercury mission and remembered Friendship 7 as “a big, significant event in my life”.

Pilot Steve Lindsey was surprised to even meet one of the Original Seven Mercury astronauts, much less fly into space with one of them. Mission Specialist Steve Robinson considered his chances of flying with Glenn as “impossible, squared”, whilst Scott Parazynski likened it to climbing Mount Everest with Sir Edmund Hillary or playing baseball with Babe Ruth. “This, for an astronaut,” said Parazynski, “is about as exciting as it gets.”

Joined by Spain’s first national spacefarer, Pedro Duque, and veteran Japanese astronaut Chiaki Mukai, the seven-strong crew of STS-95 would support more than 80 experiments in the pressurized confines of both the Spacehab and shuttle Discovery’s middeck. Moreover, they would deploy the SPARTAN satellite for two days of solar physics observations, before retrieving it and supporting a range of other external payloads.

When Discovery launched at 2:19 p.m. EDT on 29 October 1998, no fewer than a quarter-million wellwishers lined the roads and beaches of Cape Canaveral. Seconds after liftoff, a small aluminum panel, located under the shuttle’s vertical stabilizer and meant to cover the drag chute, somehow became detached and fell away.

Although its absence was not expected to impact the mission, managers could not be sure if the drag chute had been damaged or destroyed during ascent. Consequently, they elected not to deploy the chute during landing on 7 November, although Lindsey was instructed to quickly press the ARM, DEPLOY, and JETTISON switches to release it on the runway if problems cropped up.

In the meantime, three hours after launch—and using his “Payload Specialist-2” callsign—Glenn sent his first message to Mission Control, as Discovery flew over Hawaii. “Hello, Houston, this is PS2 and they got me sprung out of the middeck for a little while,” he said. “We are just going by Hawaii and that is absolutely gorgeous.”

In Mission Control, Capcom Bob Curbeam replied that he was glad that Glenn was enjoying the show.

“Enjoying the show is right,” continued the world’s first (and so far only) septuagenarian astronaut. Then, quoting a famous line from his Friendship 7 mission, he said: “The best part is…a trite old statement, Zero-G and I feel fine!” Less than two hours later, as Glenn exceeded the four hours and 55 minutes he had spent in flight aboard Friendship 7, Curt Brown noted that STS-95 had helped the senator to double his spaceflight endurance log time.

“Let the record show,” Brown reported, “that John has a smile on his face that goes from one ear to the other and we haven’t been able to remove it yet!” And that smile remained on Glenn’s face for the next nine days.

Quelle: AS