30.09.2020

"We are interested in technologies to support wide area search, narrow field tracking, and autonomous space domain awareness," says CHPS program manager Capt. David Buehler.

NASA’s planned Gateway station would operate in cislunar space.

CLARIFICATION: AFRL has clarified that the orbits under consideration are the Earth-Moon Lagrange points not the Earth-Sun Lagrange points.

WASHINGTON: The Air Force Research Lab (AFRL) has revealed first details about its groundbreaking effort to build an experimental satellite for monitoring lunar-faring spacecraft — including its possible Lagrange point orbit and plans for a kick off industry day this coming summer.

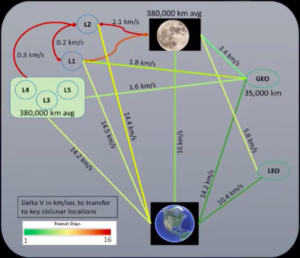

The Cislunar Highway Patrol Satellite (CHPS) would be the first space domain awareness (SDA) to focus on cislunar space, the vast region between the Earth’s outer orbit and the Moon’s. It could also be the US military’s first attempt to operate a satellite in the special orbital domains known as Lagrange Points, where a spacecraft can, in essence, ‘hover’ in a relatively fixed spot.

“We are evaluating multiple orbits for potential utility in conducting the space domain awareness mission. Most of the orbits of interest lie within the Lagrange 1 or 2 families,” program manager Capt. David Buehler, tells me in an email.

CLARIFICATION BEGINS. These orbital positions, where “the gravitational pull of two large masses precisely equals the centripetal force required for a small object to move with them,” are named after the Italian-French mathematician Josephy-Louis Lagrange who first wrote on this so-called ‘Three Body Problem’ in 1772, NASA’s website explains. There are five such points in any orbital three-body problem.

Buehler, in an email following original publication, explained that AFRL is looking at the Lagrange points between the Earth and the Moon, rather than the Earth-Sun points more commonly referenced in astronomy. The Earth-Moon L1 position lies on a straight line between the Earth and the Moon. The L2 point is on the far side of the Moon’s orbit, and is where China’s Queqiao communications satellite, launched in 2018, is orbiting to keep in contract with the lunar lander on the far side of the Moon. CLARIFICATION ENDS.

Because of its first-of-a-kind nature, the CHPS program is still in its infancy — figuring out the mission set and specific goals.

“We are in the early stages of design and are working to establish the science and technology required for domain awareness to support commercial and NASA activities beyond Geosynchronous Orbit,” Buehler said.

This includes deciding what launch vehicle would be suitable, and what sort of on-board propulsion the satellite would require to operate in L1 and L2 given that those orbits, called halo orbits, and the satellite would need to station-keep. We are evaluating multiple launch options including collaboration with NASA, procurement of commercial services, and on-board electric-propulsion-based orbit-raising,” Buehler said.

Likewise, the budget requirements for the mission, as well as a formal schedule, have yet to be nailed down. Nonetheless, if all goes well, AFRL envisions having the acquisition plan wrapped up over the next couple of weeks. The next step would be either an industry day or more formal request for information (RFI), likely in the summer, he explained.

That said, the goal is for CHPS to undertake a number of experiments to help define what will be needed to extend SDA to cislunar space on a sustainable basis.

“We are interested in technologies to support wide area search, narrow field tracking, and autonomous space domain awareness. Additionally, we are interested in communication and positioning, navigation, and timing solutions required to support the flight experiment beyond the GEO belt,” Buehler elaborated.

AFRL’s principle investigator on the project, Jaime Stearns, explained in a Sept. 3 press release announcing the new program: “We need to address really basic things that start to break down beyond GEO, like how do we even write down a trajectory. The current space catalog uses Two-Line Elements, or TLEs, which simply do not capture the complex orbital dynamics and have almost no meaning in cislunar space.”

As Breaking D readers know, military space leaders over the past year have been gradually turning up the volume on concerns about China’s long-term lunar exploration plans. China last January became the first country to land a rover on the far side of the Moon.

“The rise of China’s space program presents military, economic, and political challenges to the United States,” says a new study by Air University’s China Aerospace Studies Institute and CNA.

“This report concludes that the United States and China are in a long-term competition in space in which China is attempting to become a global power, in part, through the use of space. China’s primary motivation for developing space technologies is national security,” the study says. “However, as China’s space program advances, its commercial and scientific activities will become more prominent and will extend the competition to encompass economics and diplomacy, challenging U.S. leadership in space just as China challenges the United States across the full range of diplomatic, military and economic power.”

The Trump administration has been positioning the US for a race to open up space commerce, via NASA’s Artemis project to put US astronauts back on the Moon and eventually on Mars and a series of space policy directives aimed at promoting the space industry.

As I reported on Tuesday, this includes promoting mining of the Moon and asteroids for water, metals and rare earth minerals. “There very well could be trillions of dollars — 10s of trillions of dollars — in large deposits of platinum-group metals on the Moon. And if that’s the case, if somebody were to be able to capitalize on those discoveries, it could change the balance of power on Earth,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said.

Quelle: BREAKING DEFENSE