25.08.2020

SpaceX’s second Starship hop imminent after Raptor static fire test

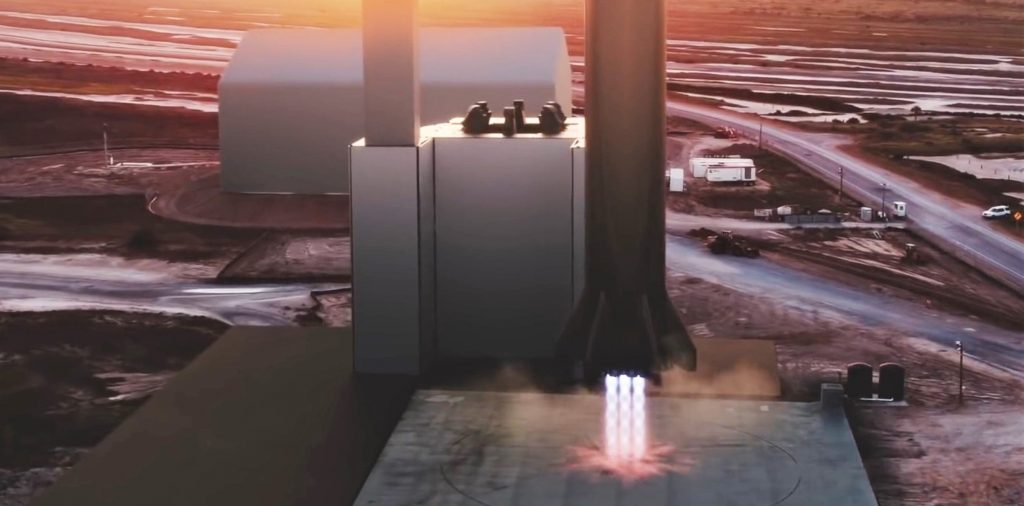

SpaceX has successfully fired up a new Starship prototype’s Raptor engine, putting the company on track for its second Starship hop test as soon as this week.

The milestone comes not long after SpaceX Starship serial number 6 (SN6) completed its first cryogenic proof, a pressure test with liquid nitrogen (LN2) used to safely verify the structural integrity of tanks (and rockets, in particular). Measuring 9m (30 ft) wide and some 30m (~100 ft) tall, SpaceX rolled Starship SN6from its Boca Chica, Texas factory to a nearby test and launch facility on August 11th and wrapped up its first acceptance test on August 16th.

Now, just seven days after its cryo proof, SpaceX has installed a new Raptor engine (SN29), prepared SN6 for a much riskier round of tests, and completed a static fire with said engine, leaving just one major step between the Starship and its hop debut. Of course, the process still had its fair share of hiccups.

SpaceX’s first SN6 static fire test window – published by Cameron County in the form of road closure notices – was set for 8 am to 8 pm CDT (UTC-5), August 23rd a few days after the Starship’s cryo proof. The first test attempt began around 9:30 am but was aborted soon after as SpaceX employees returned to the launch pad to (presumably) troubleshoot. The second attempt began around 2:30 pm, leaving a little less than half the test window available.

Attempt #2 very nearly managed to extract a static fire, aborting possibly a second or less before Raptor ignition around 3:41 pm. Once again, SpaceX teams returned to the pad after Starship was detanked and safed, briefly inspecting the general location of the rocket’s Raptor engine before once again clearing the pad around 6:30 pm. At long last, Starship SN6 began a smooth and fast flow that culminated in the ignition of Raptor SN29 around 7:45 pm, just 15 minutes before the end of SpaceX’s test window.

As with all SpaceX static fires, engineers must still analyze the data produced – and possibly inspect pad or rocket hardware – to verify vehicle health before proceeding into launch operations. Unlike all other SpaceX static fires, the company doesn’t announce the results of those tests – nor the solidified launch window – during prototype development programs. In the context of iterative aerospace development, while there may be such a thing as a “good” or “bad” test, all tests – as long as they’re performed safely and produce a large quantity of usable data – are essentially successful.

As such, it’s likely for the best that SpaceX doesn’t put the public focus on the “success” of any given test. Still, it means that unofficial educated guesses are typically the only way to determine the results of any given test and how those results impact the next steps. For SN6, the very broad-strokes conclusions one can draw from unofficial livestreams suggest that the Starship’s first Raptor static fire was a success. Assuming that the unknown cause(s) of the day’s two prior aborts were minor and easily rectified, SpaceX is likely exactly on schedule for Starship SN6’s first hop attempt.

SN6’s first flight is expected to be an almost identical copy of Starship SN5’s highly successful August 4th debut, following the same 150m (~500 ft) parabolic trajectory. Filed before SN6’s August 23rd static fire, SpaceX has penciled in Friday, August 28th for Starship SN6’s own hop debut. Thanks to the fact that SpaceX was able to complete both SN6’s cryo proof and static fire on the first day of their respective test windows, August 28th is likely well within reach. Stay tuned for updates as Starship SN6’s hop debut schedule solidifies.

Quelle: TESLARATI

----

Update: 28.08.2020

.

SpaceX kicks off orbital Starship launch pad construction in Texas

CEO Elon Musk has confirmed that SpaceX is already well into the process of building an orbital-class Starship launch pad in Boca Chica, Texas.

After much ado about nothing and a multi-day fan skirmish over whether a new SpaceX construct was meant for a water tower or launch pad, the debate can finally be brought to a close. As of almost two weeks ago, it was just shy of guaranteed that the concrete foundation SpaceX was working on would be wildly excessive for a water tower, turning it into a question of whether it would be a suborbital or orbital-class test stand for Starship.

Now, Musk has confirmed – somewhat surprisingly – that the foundation will ultimately support an “orbital launch mount” capable of hosting what will eventually be the largest and most powerful rocket ever built.

All the way back in September 2019, SpaceX actually broke ground on a separate orbital-class Starship launch pad at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A). Despite rapid progress over the next several months, work on Pad 39A’s Starship additions abruptly ground to a halt in Q1 2020 and has yet to restart.

The beginnings of the 39A Starship launch mount closely resembled a conceptual design published as part of an official 2019 SpaceX video. However, in a twist that isn’t actually much of a surprise for long-time followers of SpaceX, the company’s new orbital South Texas launch mount looks almost nothing like 2019 pad renders or the incomplete metalwork at Pad 39A.

In other words, SpaceX – probably lead by Musk himself – has substantially redesigned Starship’s orbital-class launch facilities and/or changed its approach to pad development for the next-generation rocket.

Hexagonal symmetry all the way down to the mount’s foundation pilings suggests that SpaceX’s new Starship pad design will begin with the bare minimum needed for a sturdy launch pad. SpaceX may change the design for Super Heavy but Starship’s thrust section is attached to a skirt with six strengthened sections that host landing legs and hold-down clamps. The sheer heft of ~2m (~6 ft) wide steel and rebar columns – soon to be filled with concrete – and pilings at least as wide and more than 30m (100 ft) deep certainly hints at a final structure capable of surviving the fury of Starship’s Super Heavy booster.

Barring additional changes, Super Heavy will be as tall as the entirety of a Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy rocket – first stage, second stage, and payload fairing included. Powered by up to 31 Raptor engines, the Super Heavy booster will produce upwards of 72,000 kN (16,000,000 lbf) of thrust at liftoff – nine times the thrust of Falcon 9, triple the thrust of Falcon Heavy, and double the thrust of Saturn V (the most powerful liquid-fuel rocket ever to reach orbit). Combined with Starship, the full stack will weigh roughly 5000 metric tons (11 million lbs) fully fueled. For the purpose of static fire testing and final vehicle checks after ignition but before liftoff, a Super Heavy-class launch mount will need to withstand more than 7200 tons (~16 million lbf) of force.

Meanwhile, SpaceX could be just a few days away from Starship SN6’s hop debut just beside SpaceX’s ongoing orbital launch mount construction, while an 80m (~260 ft) tall Super Heavy booster assembly building may have reached its full height earlier this week.

Quelle:TESLARATI

----

Update: 1.09.2020

.

Starship SN6 hop delayed by local weather – Super Heavy is coming

Starship SN6 was aiming to conduct a 150-meter hop test on Sunday, just a few weeks after SN5 completed the first Starship prototype launch. However, despite getting down to T-5 minutes on one of the attempts, aborts were called – highly likely to unacceptable weather conditions, specifically strong winds in the area. This was backed up by the cancellation of testing over the next few days, which are also forecast to be windy.

SN6’s test will be a near-mirror of SN5’s short flight, with both prototypes aiming to refine SpaceX’s launch and landing operations. Meanwhile, additional Starships continue to evolve, along with preparations for the Super Heavy booster, which – according to Chief Designer Elon Musk – could conduct an initial test hop by October.

SN5 and SN6:

In another sign of SpaceX Boca Chica’s production cadence, the allowance for SN6 to be ready to hop just weeks after SN5 was aided by having SN6 already assembled in the Mid Bay while SN5 was reaching 150 meters into the South Texas sky.

Both SN5 and SN6 are made from the 301 steel rings, making them near twins by way of manufacture. This was by design, allowing SN5 and SN6 to repeat the hop test multiple times to aid SpaceX’s information on the performance of the vehicle in its single Raptor configuration.

For now, the focus is on SN6’s hop, was targeting Sunday. The test was to take place within a 12-hour window that ranges from 8 am to 8 pm local time. As per usual, a police siren will sound around 10 minutes before the ignition of Raptor SN29. That occurred during the third attempt of the day before Starship’s double venting – which usually points to a detanking process – was observed.

SN5 appears to have completed post-hop processing in the Mid Bay, rolling out into the Production Facility yard to allow for a composite overwrapped pressure vessel (COPV) changeout in a clear sign SN5 will hop at least one more time.

SN8 and SN9:

The rollout of the Mid Bay was primarily to allow for the next Starship to complete stacking operations, with SN8 requiring both bays for the final stack with the aft/engine section.

SN8 will be a “full-scale” Starship, complete with a nose cone and aero surfaces, allowing it to reach the higher altitude milestone of up to 20 KM. The vehicle may initially launch to a lower altitude during its test regime.

This vehicle – made from steel rings built from a version of the 304L alloy, will host three Raptor engines to enable to achieve these higher altitudes. The aero surfaces will be employed for the landing sequence, which includes the controlled “bellyflop” approach before the Raptors push the aft towards the landing pad to touchdown on its landing legs.

Potentially akin to SN5 and SN6’s relationship, Starship SN9 is now into the business end of its construction. Also constructed from the 304L steel rings, SN9 is almost certain to receive a nose cone and aero surfaces.

However, there are clues SN9 may be another evolution on the Starship roadmap, with an increased amount of surface area shown to have attachment points for the installation of the Thermal Protection System (TPS) tiles.

Such an observation doesn’t mean this vehicle is going to be a suborbital rocket. Instead, it is likely SpaceX wants to evaluate the performance of TPS attach points during this test flight profile.

This would be prudent, not least based on the lessons learned during Shuttle, but also because a few tiles from a small patch near the aft of the vehicle have detached during Starship testing at the launch site.

SN7.1 Test Tank:

Also part of SpaceX’s test regime is another Test Tank. Designated as SN7.1, this tank is also made from the 304L steel and will be overpressurized to failure, on purpose, to allow for additional data points.

SN7.1 follows on from SN7, also a test tank, which was also pushed to failure – twice in fact. The first test resulted in what was more a leak than a failure before it was patched up and pressurized to destruction.

SN7.1 is likely to roll to the launch site, to a dedicated test stand next to the Starship launch mount. Once SN6 hops over to the landing pad, SN7.1 will be able to take the road trip for its test just days later.

Super Heavy:

The construction of these Starship prototype vehicles is ongoing, while significant construction work continues at both the Production Facility and the launch site. Both efforts are related to Super Heavy.

Work on the High Bay has reached its full height, with sections that will host the roof now being installed, while a large amount of work takes place on the lower levels to enclose the 81-meter tall facility.

This is where the sections – for what will become the world’s most powerful rocket – will be assembled.

Once assembled, the vehicle will be transported to the orbital launch site, next door to the current Starship launch area.

Construction on this launch mount is picking up the pace, with the sheathing of the rebar columns that will support the base of the mount for the Super Heavy.

While this work was seen as a major sign of progress toward the day a Super Heavy would be observed out in the open, it was widely expected that any on-site testing of such a vehicle would be next year. Elon Musk then blew that prediction out of the water on Twitter.

When noting the upcoming announcements for his numerous companies, Elon noted the next Starship update would be in October, adding: “We will have made a lot of progress by then. Might have a prototype booster hop done by then.”

While such a target is very ambitious, one of the critical paths to such a test hop of the huge Super Heavy was removed by Elon, adding the test would only require two Raptor engines.

He also added that “Raptor reached 230 mT-F (over half a million pounds of thrust) at peak pressure with some damage, so this version of the engine can probably sustain ~210 tons. Should have a 250+ ton engine in about 6 to 9 months. Target for booster is 7500 tons (16.5 million pounds) of thrust.”

With SN29 involved with the SN6 hop, earlier this month, Elon noted that testing was already up to engine SN40.

This should provide a stock of enough engines to cover SN8, SN9, and the test hop of the Super Heavy – with more engines likely to have passed Static Fire testing at SpaceX’s test facility in McGregor by the time those vehicles require them to arrive in Boca Chica.

Testing is also proceeding well with this impressive full-flow staged combustion Methalox engine, with Elon earlier adding that a “Raptor engine just reached 330 bar chamber pressure without exploding!” This is way above the usual benchmark of around 300 bar.

With an eye to orbital flight, Elon added that the version of Raptor – that will be doing a lot of the pushing once in space, the RaptorVac (RVac) – has already begun. “Testing with shorter RVac skirt went well. Full-length skirt test coming soon,” he recently tweeted.

This confirmed photos of the horizontal test stand at McGregor, showing both a standard Raptor under testing and another with a modified nozzle/skirt – highly likely to be the engine Elon was referencing.

Challenges will be ahead for Super Heavy’s development, with Elon citing the Thrust Structure – that will have to cope with hosting the power of 31 engines – being “the hardest part of the booster design.”

A job listing was also recently spotted, calling for “Starship welders in McGregor,” required to work to build the structural test stand for the Starship and Super Heavy vehicles. “The Starship welders will work with an elite team of other fabricators to rapidly build and weld the large assembly that will support vehicle structural testing at our launch site in South Texas.”

Elon also updated the landing leg set-up for Super Heavy, adding “the booster design has shifted to four legs with a wider stance (to avoid engine plume impingement in vacuum), rather than six.”

This came after a pointer to the future, where Elon confirmed most launches would eventually take place from a platform out at sea. “Will mostly launch from ocean spaceports long-term,” he noted on Twitter. These ocean spaceports would serve several purposes, not least cutting down on the issue of impacts from the firing of 31 Raptors on local communities.

With Super Heavy progressing toward testing, there remains the distinct possibility the vehicle could be conducting more ambitious test flights before the Space Launch System (SLS) conducts its maiden launch, which is currently expected to be late in 2021.

However, it unlikely to be a race between the two monster rockets.

While Elon has made no secret of his disdain for expendable rockets, such as SLS, SpaceX’s close working relationship with NASA negates a competitive edge.

It is more likely Elon’s primary motivation is related to the banner he has been flying since setting up SpaceX, the push for a reusable – thus viable – interplanetary cargo and crew transportation system that can be the enabler to make life multi-planetary.

Quelle: NS

----

Update: 3.09.2020

.

Musk emphasizes progress in Starship production over testing

WASHINGTON — SpaceX Chief Executive Elon Musk said the company is making “good progress” on its next-generation Starship launch vehicle despite delays in the schedule of test flights of the vehicle.

In an interview broadcast during the Humans to Mars Summit by the advocacy group Explore Mars Aug. 31, Musk emphasized the progress the company has made not on test flights of the vehicle but instead development of production facilities for Starship at Boca Chica, Texas.

“We’re making good progress. The thing that we’re really making progress on with Starship is the production system,” he said, referring to the growing campus at Boca Chica. “A year ago there was almost nothing there and now we’ve got quite a lot of production capability.”

Those facilities have cranked out a series of prototypes of Starship, which is intended to serve as the upper stage of the overall launch system. Musk said that construction will start this week on “booster prototype one,” a reference to the Super Heavy first stage of the system.

That production capability, he argued, is essential to the long-term development of the overall launch system. “Making a prototype of something is, I think, relatively easy,” he said. “But building the production system so that you can build ultimately hundreds or thousands of Starships, that’s the hard part.”

That focus on production belies the lack of progress on actual testing of the vehicle. At a September 2019 event at Boca Chica, Musk, with a Starship prototype standing behind him, said that the vehicle would fly to an altitude of 20 kilometers in one or two months. “I think we want to try to reach orbit in less than six months,” he said, a schedule he said at the time was accurate to “within a few months.”

Eleven months later, a Starship prototype has flown only once: an Aug. 4 “hop” test of a prototype known as SN5 that flew to an estimated altitude of 150 meters before landing on a nearby pad. Another prototype, SN6, was being prepared for a similar hop test Aug. 30 that was scrubbed for undisclosed reasons. Four other prototypes were destroyed in ground tests prior to the SN5 flight.

Musk, asked when Starship would make its first orbital flight, said, “Probably next year.” He didn’t specify if that would be the Starship vehicle alone or the full stack with the Super Heavy booster. “I hope we do a lot of flights. The first ones might not work. This is uncharted territory. Nobody’s ever made a fully reusable orbital rocket.”

He later said he expected the launch system, ultimately intended to transport people to Mars, will do “hundreds of missions with satellites before we put people on board.”

Musk quoted a cost estimate for developing Starship of $5 billion, a figure he has stated in the past. He played down the NASA Human Landing System award the company received in April, valued at $135 million, to study using the Starship system as a means for landing NASA astronauts on the moon for the Artemis program. “Definitely the NASA support is appreciated,” he said. “It’s helpful, but it’s not a gamechanger.”

The overall design of the system is still evolving. While SpaceX previously described Super Heavy as having 31 Raptor engines, Musk said the final number may be less. “We might have fewer than 31 engines on the booster, because we’re trying to simplify the configuration,” he said. “It might be 28 engines. It’s still a lot of engines.”

Musk spent a large chunk of the nearly half-hour interview going into technical details about the Raptor engines that will power Starship, discussing chamber pressures, thrust-to-weight ratios and specific impulse. But asked what he thought what sort of headline would accompany a successful human Mars landing, he was stumped. “I haven’t thought about that at all,” he said, settling on “humanity is on Mars.”

“We need a lot of people fired up to go to Mars,” he said. “It’s going to be kind of risky, but kind of a cool, fun adventure.”

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 25.09.2020

.

SpaceX Starship pop test opens the door for 60,000 foot hop [update]

SpaceX has successfully destroyed a Starship ‘test tank’ for the fourth time, opening the door for the first high-altitude prototype to roll to the launch pad as soon as tomorrow.

The culmination of three nights and more than 20 hours of concerted effort, SpaceX was finally able to fill Starship test tank SN7.1 with several hundred tons of liquid nitrogen before dawn on September 23rd. With just an hour left in the day’s test window, SpaceX closed the tank’s vents, allowing its cryogenic contents to boil into gas and expand with no outlet. At 4:57 am CDT, SN7.1 burst, bringing its lengthy test campaign to a decisive end.

A handful of hours later, new road closure notices revealed SpaceX’s plan to roll Starship SN8 – the first full-size prototype and first ship meant for high-altitude testing – from its Boca Chica factory to the launch site.

Update: All road closures planned for Starship SN8’s roll to the launch pad (Sept 24) and first test campaign (Sept 27-29) have been canceled. Stay tuned for updates on the high-altitude prototype’s test schedule.

Short of new information from SpaceX or CEO Elon Musk, little is known about the results of SN7.1’s lengthy test campaign, but the fact that it survived two nights of nondestructive testing – including the use of hydraulic rams to simulate Raptor thrust – effectively clears Starship SN8 for suborbital testing. Based on a speculative, amateur analysis of the aftermath of SN7.1’s burst test, it can also be tentatively concluded that the tank failed almost exactly where one would expect it to: the in-situ weld attaching the upper tank dome to SN7.1’s steel ring hull.

SN7.1’s forward dome appears to have cleanly sheared off around much of its circumferential weld joint – exactly what one would theoretically expect from a good, uniform weld. Assuming that SN7.1 reached pressures well above 8.5 bar (~125 psi) before it burst, the tank’s final test can likely be deemed a success.

The very same day SpaceX kicked off what would become Starship SN7.1’s last burst test attempt, teams worked to install functional flaps on a full-scale Starship prototype (SN8) for the first time ever. Effectively answering the question of whether SpaceX would fully outfit the ship with a nosecone and flaps before its first acceptance tests, SN7.1’s successful pop was followed by road closure notices for SN8’s transport to the launch pad around dawn on September 24th and cryptic “SN8 Testing” as early as September 27th.

As of September 23rd, SN8’s twin aft flaps – large aerodynamic control surfaces meant to stabilize free-falling Starships – have been fully installed alongside ‘aerocovers’ that will protect each flap’s control mechanisms. The only hardware Starship SN8 is missing is a ~20m (~60 ft) tall nosecone, two smaller forward flaps, and the plumbing needed to access a smaller liquid oxygen “header” tank located in the tip of said nose.

At the moment, SpaceX has installed one Starship nosecone prototype atop five unpressurized rings – creating a full nosecone stack. That particular prototype has no liquid oxygen header tank, however, meaning that SpaceX would likely need at least a day or two to weld one of the noses with a header tank atop one of several finished five-ring sections. In other words, to transport SN8 to the pad tomorrow, there’s almost no chance that SpaceX will have time to finish and install a proper nosecone on the prototype, meaning that the company has chosen to test the Starship before that milestone.

Doing so should reduce any inconvenience caused by vehicle failure in the event that Starship SN8’s acceptance test campaign doesn’t go as planned. In hindsight, the inclusion of Starship SN8’s aft flaps and aerocovers during the ship’s first major tests was likely a necessity, given that almost half of each flap and its support structure is installed directly to the skin of its liquid oxygen tank. Theoretically, when chilled to the temperature of liquid nitrogen or oxygen, the diameter of the stainless steel rings Starship SN8 is built out of could shrink by as much as 0.3% (~20 mm or ~0.8 in).

Only half of Starship SN8’s aft flaps will be directly subject to that tank contraction, resulting in a relatively complex environment for such a large, high-stress mechanical system. As such, testing flap actuation under cryogenic loads is likely a critical part of SN8’s cryogenic proof test, otherwise meant to demonstrate the structural integrity and functionality of Starship’s propellant tanks. If SN8 rolls to SpaceX’s launch facilities on schedule, the Starship’s first cryogenic proof test could begin as early as 9pm CDT (UTC-5) on Sunday, September 27th.

Quelle: TESLARATI