.

Lunar Orbiter image of the 93-mile-wide Copernicus Crater with this bright central peaks.

.

Strange minerals detected at the centers of impact craters on the moon may be the shattered remains of the space rocks that made the craters and not exhumed bits of the moon's interior, as had been previously thought.

The foreign matter in the craters is probably asteroid debris and some could even be from Earth, which has thrown off its share of material as it's been battered by asteroids and comets over the eons.

The discovery comes not from finding anything new in the craters themselves, but by planetary scientists who were looking at models of how meteorite impacts affect the moon. Specifically, the researchers simulated some high-angle, exceptionally slow impacts -- at least slow compared to possible impact speeds -- and they were surprised at what they found.

"Nobody has done it at such high resolution," said planetary scientist Jay Melosh of Purdue University. Melosh and his colleagues published a paper on the discovery in the May 26 online issue of the journal Nature Geoscience.

They found that when a slow enough impact happened, at speeds of less than 27,000 miles per hour (43,000 kph), the rock that struck doesn't necessarily vaporize. Instead, it gets shattered into a rain of debris that is then swept back down the crater sides and piles up in the crater's central peak.

In the case of craters like Copernicus (pictured top), the foreign material stands out because it contains minerals called spinels. These only form under great pressure -- in the Earth's mantle, for instance, and perhaps in the mantle of the moon. But spinels are also common in some asteroids, said Melosh, which are fragments of broken or failed planets from earlier days in the formation of our solar system.

The team has concluded, therefore, that the unusual minerals observed in the central peaks of many lunar impact craters are not lunar natives, but imports.

That conclusion could also explain why the same minerals, if they were instead from the interior of the moon, are not found in the largest impact basins -- as would be expected if the impact event was larger and penetrated deeper into the moon.

"An origin from within the Moon does not readily explain why the observed spinel deposits are associated with craters like Tycho and Copernicus instead of the largest impact basins," writes Arizona State University researcher Erik Asphaug in a commentary on the paper. "Excavation of deep-seated materials should favor the largest cratering events."

The new impact modeling also implies that pockets of early Earth material might be in cold storage on the moon, says Asphaug. The young Earth was bombarded with asteroids that sent terrestrial debris into space at speeds that were pretty slow and within the range of this model.

“Even more provocative,” explains Asphaug, “is the suggestion that we might someday find Earth’s protobiological materials, no longer available on our geologically active and repeatedly recycled planet, in dry storage up in the lunar ‘attic’.”

.

Quelle: Discovery-News

.

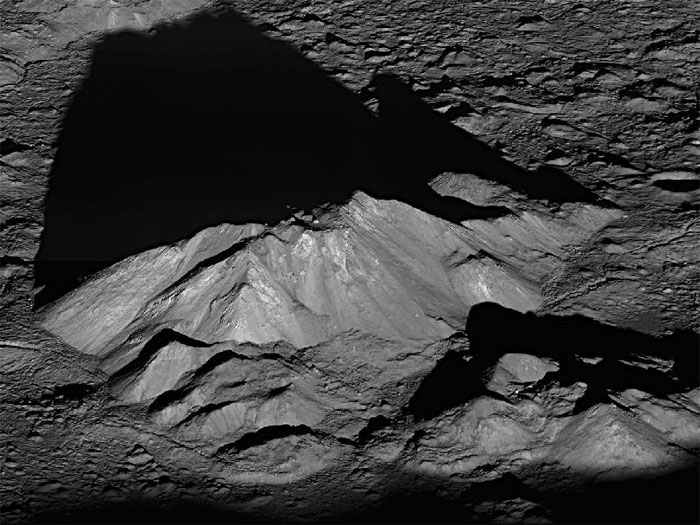

Sunrise shadows on the moon's Tycho crater, as seen by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter on June 10, 2011. NASA released the photo on June 30.

CREDIT: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/Arizona State University

5152 Views