29.06.2020

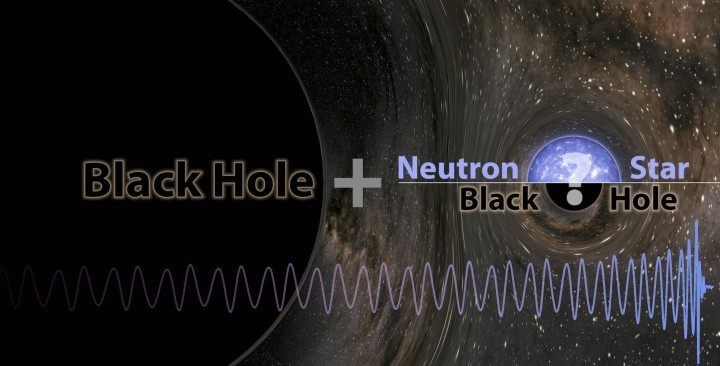

For decades astronomers have been puzzled by a gap that lies between neutron stars and black holes, but a major new discovery has found a mystery object in this so-called ‘mass gap’.

The gravitational wave group from the University of Portsmouth’s Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation played a key role in the study, which will change how scientists look at neutron stars and black holes.

When the most massive stars die, they collapse under their own gravity and leave behind black holes. When stars that are a bit less massive die, they explode in a supernova and leave behind dense, dead remnants of stars called neutron stars.

Gravitational waves are emitted whenever an asymmetric object accelerates, with the strongest sources of detectable gravitational waves being from the collision of neutron stars and black holes. Both of these objects are created at the end of a massive star’s life.

The heaviest known neutron star is no more than two and a half times the mass of our sun, or 2.5 solar masses, and the lightest known black hole is about five solar masses.

The reason these findings are so exciting is because we’ve never detected an object with a mass that is firmly inside the theoretical mass gap between neutron stars and black holes before.

The new study from the National Science Foundation's Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the Virgo detector in Europe, has announced the discovery of an object of 2.6 solar masses, placing it firmly in the mass gap.

LIGO consists of two gravitational-wave detectors which are 3,000 kilometres apart in the USA - one in Livingston, Louisiana, and one in Hanford, Washington. The Virgo detector is in Cascina, Italy.

Dr Laura Nuttall, a gravitational wave expert from the University’s Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation, said: “The reason these findings are so exciting is because we’ve never detected an object with a mass that is firmly inside the theoretical mass gap between neutron stars and black holes before. Is it the lightest black hole or the heaviest neutron star we’ve ever seen?”

Portsmouth PhD student Connor McIsaac ran one of the analyses that computed the significance of this event.

Dr Nuttall added: "Connor's analysis makes us certain that this is a real astrophysical phenomenon and not some strange instrumental behaviour.”

The object was found on August 14, 2019, as it merged with a black hole of 23 solar masses, generating a splash of gravitational waves detected back on Earth by LIGO and Virgo.

The cosmic merger described in the study, an event dubbed GW190814, resulted in a final black hole about 25 times the mass of the sun (some of the merged mass was converted to a blast of energy in the form of gravitational waves). The newly formed black hole lies about 800 million light-years away from Earth.

Before the two objects merged, their masses differed by a factor of 9, making this the most extreme mass ratio known for a gravitational-wave event. Another recently reported LIGO-Virgo event, called GW190412, occurred between two black holes with a mass ratio of 3:1.

Vicky Kalogera, a professor at Northwestern University in the United States, said: "It's a challenge for current theoretical models to form merging pairs of compact objects with such a large mass ratio in which the low-mass partner resides in the mass gap. This discovery implies these events occur much more often than we predicted, making this a really intriguing low-mass object.

"The mystery object may be a neutron star merging with a black hole, an exciting possibility expected theoretically but not yet confirmed observationally. However, at 2.6 times the mass of our sun, it exceeds modern predictions for the maximum mass of neutron stars, and may instead be the lightest black hole ever detected."

I think of Pac-Man eating a little dot, when the masses are highly asymmetric, the smaller neutron star can be eaten in one bite.

According to the LIGO and Virgo scientists, the August 2019 event was not seen by light-based telescopes for a few possible reasons. First, this event was six times farther away than the merger observed in 2017, making it harder to pick up any light signals. Secondly, if the collision involved two black holes, it likely would have not shone with any light. Thirdly, if the object was in fact a neutron star, its 9-fold more massive black-hole partner might have swallowed it whole; a neutron star consumed whole by a black hole would not give off any light.

"I think of Pac-Man eating a little dot," said Kalogera. "When the masses are highly asymmetric, the smaller neutron star can be eaten in one bite."

Future observations with LIGO, Virgo, and possibly other telescopes may catch similar events that would help reveal whether the mystery object was a neutron star or a black hole, or whether additional objects exist in the mass gap.

The paper about the detection has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Quelle: UNIVERSITY OF PORTSMOUTH

+++

Gravitational wave scientists grapple with the cosmic mystery of GW190814

A highly unusual gravitational wave signal, detected by the LIGO and Virgo observatories in the US and Italy, was generated by a new class of binary systems (two astronomical objects orbiting around each other), an international team of astrophysicists has confirmed.

Scientists from the LIGO and Virgo Collaboration, which includes researchers from the Institute for Gravitational Wave Astronomy at the University of Birmingham, detected the signal, named GW190814, in August 2019.

In a new paper, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the team has announced that the signal was generated by a compact object - a neutron star or a black hole - 2.6 times the mass of our sun (2.6 solar masses), merging with a black hole of 23 solar masses.

The new observation is important because it challenges astrophysicists' understanding both of how stars die and how they pair up into binary systems. Although the precise nature of the lighter member of the binary that generated GW190814 is unknown, scientists have confirmed that it is a record breaker: it is more massive than any neutron star and lighter than any black hole yet observed.

“This merger event is one of the most unusual ones observed in gravitational waves to date”, says Dr Patricia Schmidt, Lecturer at the Institute for Gravitational Wave Astronomy and member of the LIGO team. “It pushes our understanding of the nature of the lighter companion and how it is formed to the limits. This will keep astrophysicists occupied for a while.”

Scientists have so far believed that dying stars do not leave remnants, whatever their nature, with a mass between 2.5 and 5 times the mass of the Sun. Now this desert has been populated by one of the objects that produced GW190814.

“From the very outset it was clear that this was a special event,” says Dr Geraint Pratten, a researcher at the Institute for Gravitational Wave Astronomy, who was involved in producing the initial sky-maps for optical telescopes’ follow-ups. “It highlights the need for ever better theoretical models of the emitted gravitational-wave signal, such as those produced here in Birmingham, to mine as much information as possible from the data and understand how such high mass-ratio binaries are formed.“

An additional aspect requires further investigation. The disparity in masses between the two objects, with the black hole nine times more massive than its companion object, challenges existing theories about how binary systems of black holes and neutron stars are formed. What is certain, according to the research team, is that GW190814 was produced by a binary system that is quite different from other systems detected so far by LIGO and Virgo.

“We have been itching with excitement since this candidate showed up on our screens,” says co-author Professor Alberto Vecchio, director of the Institute for Gravitational Wave Astronomy. “We thought the Universe would be kind of lazy in producing binaries of objects with such different masses, if it did so at all. And guess what, we were wrong! We now know there are cosmic factories hiding somewhere that are actually rather efficient at generating these systems. The journey to figure out what they are and how they work is going to keep us busy for quite some time, but more and better data from LIGO and Virgo are just about a year away, and we are bound to have new surprises”.

A further mystery surrounding GW190814 has been its elusiveness for astronomers looking for light from the event. When new gravitational waves are detected, an alert is sent to astronomers world-wide, triggering dozens of ground- and space-based telescopes to start searching for a fireball ignited by the collision. For GW190814, no such glow has yet been detected.

Dr Matt Nicholl is a Lecturer at the Institute for Gravitational Wave Astronomy, and followed up the event as part of the European ENGRAVE team using the ESO Very Large Telescope, and the US-led team using the Magellan telescopes. He says: “Observatories around the world carried out an intensive search for any light-show produced by the merger. We were able to show that if any light was released, it must have been extremely faint to avoid detection. This means that if the lighter companion was a neutron star, its more massive black hole partner may have simply swallowed it whole! On the other hand, if the collision involved two black holes, it’s not likely that it would have shone with any light.”

LIGO research activities at the University of Birmingham are supported by the U.K. Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC). Additional funding was received from the Royal Astronomical Society, the NWO (Dutch Research Council), and the Royal Society and Wolfson Foundation.

Quelle: University of Birmingham

+++

LIGO-Virgo finds mystery astronomical object in ‘mass gap’

Object lies between heaviest known neutron star and lightest known black hole

An international research collaboration, including Northwestern University astronomers, has detected a mystery object inside the puzzling area known as the “mass gap” -- the range that lies between the heaviest known neutron star and the lightest known black hole. The finding has important implications for astrophysics and the understanding of low-mass compact objects.

When the most massive stars die, they collapse under their own gravity and leave behind black holes; when stars that are a bit less massive than this die, they explode in a supernova and leave behind dense, dead remnants of stars called neutron stars. The heaviest known neutron star is no more than 2.5 times the mass of our sun, or 2.5 solar masses, and the lightest known black hole is about 5 solar masses. For decades, astronomers have wondered: Are there any objects in this mass gap?

Now, in a new study from the National Science Foundation’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the European Virgo observatory, scientists have announced the discovery of an object of 2.6 solar masses, placing it firmly in the mass gap.

The intriguing object was found on Aug. 14, 2019, as it merged with a black hole of 23 solar masses, generating a splash of gravitational waves detected back on Earth by LIGO and Virgo. A paper about the detection was published today (June 23) by The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“Mergers of a mixed nature -- black holes and neutron stars -- have been predicted for decades, but this compact object in the mass gap is a complete surprise,” said Northwestern’s Vicky Kalogera, who coordinated writing of the paper. “We are really pushing our knowledge of low-mass compact objects. Even though we can’t classify the object with conviction, we have seen either the heaviest known neutron star or the lightest known black hole. Either way, it breaks a record.”

Kalogera, a leading astrophysicist in the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC), is an expert in the astrophysics of compact object binaries and analysis of gravitational-wave data. She is the Daniel I. Linzer Distinguished University Professor of Physics and Astronomy and director of CIERA (Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics) in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences.

“Whereas we are not sure about the nature of the low-mass compact object, we have obtained a very robust measure of its mass, which falls right into the so-called mass gap,” said Mario Spera, a co-author of the paper who studies the formation of merging binaries. He is a Virgo collaboration member and a European Union Marie Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at CIERA and the University of Padova.

“This exciting and unprecedented finding, combined with the unique mass ratio of the merger event, challenges all the astrophysical models that try to shed light on the origins of this event,” Spera said. “However, we are quite sure that the universe is telling us, for the umpteenth time, that our ideas on how compact objects form, evolve and merge are still very fuzzy.”

The cosmic merger described in the study, an event dubbed GW190814, resulted in a final black hole about 25 times the mass of the sun. (Some of the merged mass was converted to a blast of energy in the form of gravitational waves). The newly formed black hole lies about 800 million light-years away from Earth.

Before the two objects merged, their masses differed by a factor of nine, making this the most extreme mass ratio known for a gravitational-wave event. Another recently reported LIGO-Virgo event, called GW190412, occurred between two black holes with a mass ratio of about 4:1.

In addition to Kalogera and Spera, the other Northwestern researchers involved in the study are Chase Kimball, Christopher Berry and Mike Zevin. The three are authors of the paper and members of CIERA.

Kimball, an astronomy Ph.D. student and LSC member, assessed how often mergers such as GW190814 occur in the universe. Berry, the CIERA Board of Visitors Research Professor, is a member of the LSC Editorial Board for all LSC publications and served as the lead representative for this study. Zevin, an astronomy Ph.D. student and LSC member, contributed to the astrophysical interpretation and also to writing the GW190412 discovery paper.

“It’s a challenge for current theoretical models to form merging pairs of compact objects with such an extreme mass ratio in which the low-mass partner resides in the mass gap,” Kalogera said. “This discovery implies these events occur much more often than we predicted, making this a really intriguing low-mass object.

“The mystery object may be a neutron star merging with a black hole -- an exciting possibility expected theoretically but not yet confirmed observationally,” she said. “However, at 2.6 times the mass of our sun, it exceeds modern predictions for the maximum mass of neutron stars and may instead be the lightest black hole ever detected.”

“Whether or not the object is a heavy neutron star or a light black hole, the discovery is the first in a new class of binary mergers,” Kimball added. “Models of binary populations will have to account for how often we now can infer that these sort of events occur.”

When the LIGO and Virgo scientists spotted this merger, they immediately sent out an alert to the astronomical community. Dozens of ground- and space-based telescopes followed up in search of light waves generated in the event, but none picked up any signals.

So far, such light counterparts to gravitational-wave signals have been seen only once, in an event called GW170817. The event, discovered by the LIGO-Virgo network in August of 2017, involved a fiery collision between two neutron stars that was subsequently witnessed by dozens of telescopes on Earth and in space. Neutron star collisions are messy affairs with matter flung outward in all directions and are thus expected to shine with light. Conversely, black hole mergers, in most circumstances, are thought not to produce light.

According to the LIGO and Virgo scientists, the August 2019 event was not seen in light for a few possible reasons. First, this event was six times farther away than the merger observed in 2017, making it harder to pick up any light signals. Secondly, if the collision involved two black holes, it likely would have not shone with any light. Thirdly, if the object was in fact a neutron star, its nine-fold more massive black-hole partner might have swallowed it whole; a neutron star consumed whole by a black hole would not give off any light.

“I think of Pac-Man eating a little dot,” says Kalogera. “When the masses are highly asymmetric, the smaller compact object can be eaten by the black hole in one bite.”

How will researchers ever know if the mystery object was a neutron star or black hole? Future observations with LIGO and possibly other telescopes may catch similar events that would help reveal whether additional objects exist in the mass gap.

“The mass gap has been an interesting puzzle for decades, and now we’ve detected an object that fits just inside it,” said Pedro Marronetti, program director for gravitational physics at the National Science Foundation (NSF). “That cannot be explained without defying our understanding of extremely dense matter or what we know about the evolution of stars. This observation is yet another example of the transformative potential of the field of gravitational-wave astronomy, which brings novel insights to light with every new detection.”

The Astrophysical Journal Letters paper is titled “GW190814: Gravitational Waves from the Coalescence of a 23 M Black Hole with a 2.6 M Compact Object.”

Additional information about the gravitational-wave observatories:

LIGO is funded by the NSF and operated by Caltech and MIT, which conceived of LIGO and lead the project. Financial support for the Advanced LIGO project was led by the NSF with Germany (Max Planck Society), the U.K. (Science and Technology Facilities Council) and Australia (Australian Research Council-OzGrav) making significant commitments and contributions to the project. Approximately 1,300 scientists from around the world participate in the effort through the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, which includes the GEO Collaboration. A list of additional partners is available.

The Virgo Collaboration is currently composed of approximately 520 members from 99 institutes in 11 different countries including Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. The European Gravitational Observatory (EGO) hosts the Virgo detector near Pisa in Italy and is funded by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France, the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) in Italy and Nikhef in the Netherlands. A list of the Virgo Collaboration groups is available.

Quelle: Northwestern University