8.04.2020

One year on from publishing the first ever image of a black hole, the team behind that historic breakthrough is back with a new picture.

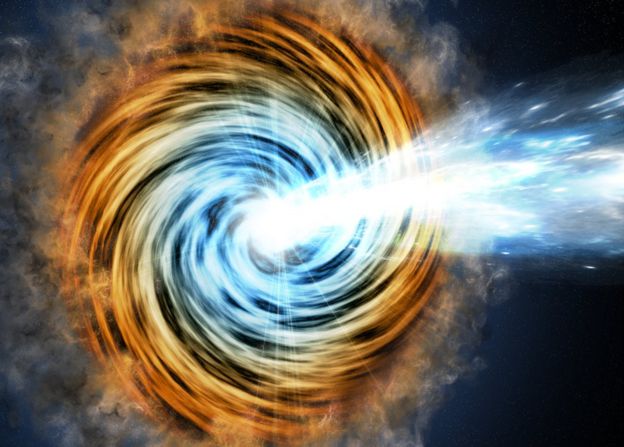

This time we're being shown the base of a colossal jet of excited gas, or plasma, screaming away from another black hole at near light-speed.

The scene was actually in the "background" of the original target.

The scientists who operate the Event Horizon Telescope describe the jet in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

They say their studies of the region of space known as 3C 279 will help them better understand the physics that drives behaviour in the vicinity of black holes.

3C 279 is what astronomers term a quasar - the extremely bright core of a very distant galaxy. This one is about 5.5 billion light-years from Earth.

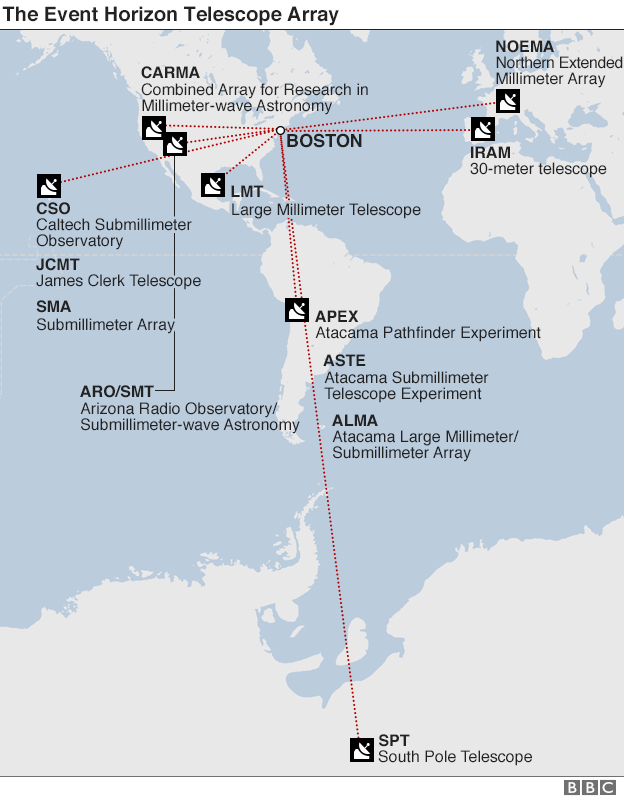

It is well known, and was used as the calibration target to align the performance of the EHT's eight individual radio telescopes when they simultaneously made their astonishing map of the supermassive black hole at the centre of Galaxy M87.

The remarkable resolution achieved by the EHT - put to such great effect with M87 - pays dividends again with 3C 279, because we see previously unrecognised features.

Image copyrightEHT COLLABORATION

Image copyrightEHT COLLABORATION

3C 279 also has a supermassive black hole at its heart. It's about one billion times the mass of our Sun and its gravity is pulling in and shredding any stars or gas that get too close. This material is likely being accreted on to a disc that winds around the hole, but some of it is being shot back out into space along two jets moving in opposite directions.

In previous images of 3C 279, we've been able to detect the outline of the jet coming that moves towards us (the one moving in the opposite direction is not detected). But in the new EHT picture, we can resolve detail close to the point where this jet leaves the black hole. What's more, this base area seems twisted and somewhat offset from the main axis of the jet.

"It's curious," said EHT Collaboration member Dr Ziri Younsi. "We're seeing a region that's actually pretty close to the black hole. It could be an interaction layer where the jet couples to the accretion disc and extracts all of its energy from the black hole.

"We don't really understand how jets are powered by black holes. Black holes, when they rotate rapidly, are the most efficient liberators of energy in the Universe, but the mechanism by which the jet can extract that energy is unknown. There are a few ideas, but we're not sure yet which one is the right one," the University College London, UK, researcher told BBC News.

The data in the images of M87 and 3C 279 was collected by the ENT's widely dispersed array of radio telescopes in 2017. The project has gone on to collect data on the supermassive black hole that exists at the centre of our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

"We have that data - of a region we call Sagittarius A*," said Dr Younsi. "We are working on it right now and although we have some preliminary results, these can't be shared just yet. We hope to have something perhaps before the end of this year." The team finds itself in a position to concentrate on this analysis because the observational time it had booked on the EHT array for this year got cancelled in the coronavirus outbreak.

A PDF of the A&A paper describing 3C 279 is available here. Its lead author is Dr Jae-Young Kim from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany.

The Event Horizon Telescope is a "virtual telescope" that links a large array of radio receivers - from the South Pole, to Hawaii, to the Americas and Europe. It uses a technique called very long baseline array interferometry (VLBI). This combines the observations from the dispersed network to mimic a telescope aperture that can produce the resolution necessary to perceive a pinprick on the sky. For the EHT, this pinprick is measured in microarcseconds.

To convey such performance to the general public, EHT team-members talk about the sharpness of vision as being the equivalent of seeing from Earth something the size of a grapefruit on the surface of the Moon.

Image copyrightM.WEISS/CFA

Image copyrightM.WEISS/CFA

Quelle: BBC