The Bion M1 mission is managed by Roscosmos, the Russian Federal Space Agency, but scientists from the United States, Germany, Canada, Poland, the Netherlands and other countries are participating in the experiments.

NASA selected nine U.S. scientists to collaborate with Russian researchers in cooperative experiments.

"We are participating in a biospecimen sharing program and utilizing hardware developed by our Russian partners that has flown successfully for many missions over the last 30 years," said Nicole Rayl, manager of the space biology division at NASA's Ames Research Center. "This way we can leverage off existing capabilities while still meeting NASA's scientific goals."

The NASA-sponsored research is focused on Bion M1's rodents, Rayl wrote in an email to Spaceflight Now.

"They will study the effects of space travel on multiple tissues, such as blood vessels, spine, knee and elbow joints and the gravity-sensing structures of the inner ear," Rayl said.

Bion M1 is Russia's first Bion mission since 1997, and it is the longest flight in the history of Russia's animal-in-space research program. Scientists are hopeful the 30-day flight duration will yield more useful data on how organisms respond to spaceflight.

.

The returnable capsule of a biological research satellite has landed in the Russian Orenburg Region near the border with Kazakhstan, bringing mice, Mongolian gerbils, geckos and various microorganisms and plants back to Earth after their month-long flight, Mission Control said on Sunday.

“The descent vehicle separated from the equipment module of the Bion-M spacecraft at 6:32 a.m. Moscow time [02:32 GMT]. After successfully passing through the dense layers of the Earth’s atmosphere, the capsule landed at 07:12 Moscow time at the designated area, about 100 km [62 miles] northeast of Orenburg,” Mission Control said.

Specialists of the Progress Space Research and Production Space Center and the Institute of Medical and Biological Studies arrived at the site of the capsule landing and started to open the hatches to bring the animals out of the capsule, one of the specialists told RIA Novosti.

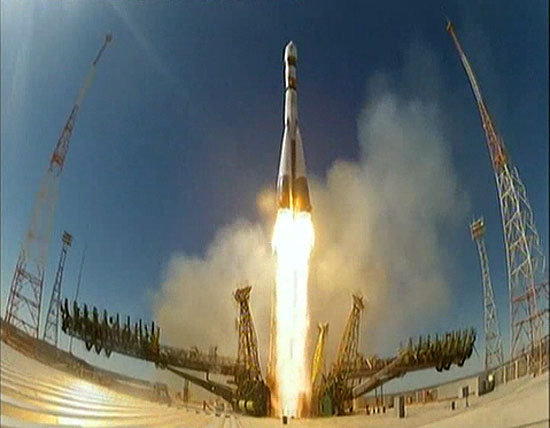

Russia launched the Bion-1M satellite, its first biological research satellite since 2007, on April 19 to conduct fundamental and applied research in space biology, physiology and biotechnology while in orbit and help pave the way for future interplanetary flights, according to the Federal Space Agency Roscosmos.

Bion-M1 carried eight Mongolian gerbils, 45 mice, 15 geckos, snails and containers with various microorganisms and plants.

During its 30-day flight, more than 70 physiological, morphological, genetic and molecular-biological experiments were conducted in support of long-duration interplanetary flights including Mars missions.

The research program included experiments with rodents to study the organism’s systemic reactions to microgravitation, as well as the impact of radiation and microgravitation on the organism.

Quelle: RIANOVOSTI

.

Update: 20.05.2013

.

MOSCOW: A number of mice and eight gerbils sent into space in a Russian capsule destined to find out how well organisms can withstand extended flights perished during their journey, scientists said as the month-long mission touched back down on Earth.

Most of the 45 mice sent into orbit – along with the gerbils and 15 newts – died on the mission, which nevertheless returned with data that scientists hope will pave the way for a manned flight to Mars.

The animals on board the Bion-M craft died because of equipment failure or due to the stresses of space, scientists said.

The craft itself landed softly early on Sunday with the help of a special parachute system in the Orenburg region about 1,200 kilometres (750 miles) southeast of Moscow. It was also carrying snails, some plants and microflora.

“This is the first time that animals have been put in space on their own for so long,” Vladimir Sychov of the Russian Academy of Sciences announced upon the peculiar crew’s return to Earth.

But at the end of the experiment, “less than half of the mice made it – but that was to be expected,” Sychov told Russian news agencies. “Unfortunately, because of equipment failure, we lost all the gerbils.”

The TsSKB-Progress space research centre’s department head, Valery Abrashkin, said on the day the mission took off in April that the study was aimed at determining how bodies adapt to weightlessness “so that our organisms survive extended flights”.

The space adventure has been widely praised by Russian state media as a unique experiment that no other country has yet pulled off. Russia last sent mice into space in 2007 for a much shorter duration of 12 days.

France’s Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) space centre said 15 of the 45 mice came from a French research lab that is cooperating with the study.

CNES life science department head Guillemette Gauquelin-Koch said the project took “a further decisive step in human adaptation to weightlessness”.

Scientists from both countries said the animals were used as it was impossible to conduct the experiment on the humans who are currently operating the International Space Station (ISS).

They added that the mice would have posed a health risk if simply placed on board the ISS for a month.

The experiment’s designers said the tests primarily focused on how microgravity impacts the skeletal and nervous systems as well as organisms’ muscles and hearts.

The animals were stored inside five special containers that automatically opened after reaching orbit and closed once it was time to return.

Also on board were over two dozen measuring devices and other scientific objects that measured everything from heart rates and blood pressure to radiation levels.

The capsule spun 575 kilometres (357 miles) above Earth.

Officials at France’s CNES said a new mission with microorganisms may be launched by Russia next year.

Russia has long set its sights on Mars and is now targeting 2030 as the year in which it could begin creating a base on the Moon for flights to the Red Planet.

But recent problems with its once-vaunted space programme – including the embarrassing failure of a research satellite that Moscow tried sending up to one of Mars’s moons last year – have threatened Russia’s future exploration efforts.

Russia’s trials and tribulations are watched closely by other space-faring nations because the Soyuz rocket on which the animals went up represents the world’s only manned link to the constantly staffed ISS.

Quelle: COSMOS

.

Update: 21.05.2013

A crew of Mongolian gerbils may have gone where no Mongolian gerbil has gone before, but they did not come back alive. A Russian spacecraft filled with mice, lizards and other animals has returned to Earth -- but with the majority of its furred passengers apparently dead.

The Bion-M experiment, launched from Baikonur, Kazakhstan, on April 19, carried 45 mice, 15 geckos, 18 Mongolian gerbils, 20 snails and a number of different plants, seeds and microorganisms, according to a Russian state news site.

About half of the mice died, but the lizards reportedly survived. The Mongolian gerbils all expired, apparently due to an equipment failure, said Vladimir Sychev of the Russian Academy of Sciences, according to AFP.

The satellite was sent into a near-Earth orbit some 357 miles above Earth, far higher than the International Space station. Lasting 30 days, the mission represented the longest time that Russian animal astronauts had been sent into space. A previous mission in 2007 lasted 12 days and only went up to about 174 miles in altitude.

Perhaps ironically, the ill-fated Mongolian gerbils were thought to have an advantage in space, since the rodents live in harsh environments and can survive without water for relatively long periods, according to an agency release weeks before the launch. Half the mice were expected to die during the journey, according to Sychev.

Although many of the animals died, they will still provide the researchers with valuable science: Each animal was numbered and implanted with a tiny microchip that would contain the "entire biography of the animal," according to an agency Web page.

Quelle: Los Angeles Times

.

Update: 23.05.2013

Omegahab: Mini-Ökosystem wieder zurück auf der Erde

.

Nach 30 Tagen im All ist am 19. Mai 2013 um 9:12 Uhr Ortszeit (12:12 Uhr MESZ) die unbemannte russische BION-M1-Rückkehrkapsel mitten in einem Sonnenblumenfeld in Südrussland gelandet. Damit ging für die deutschen Wissenschaftler das vom Deutschen Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) geförderte Mini-Ökosystem-Projekt "Omegahab" mit einem lachenden und einem weinenden Auge zu Ende: Noch nie haben Tiere eine längere Zeitspanne alleine in einem höheren Orbit verbracht. Doch in 575 Kilometern Höhe gab es allerdings auch Verluste: Einige Bewohner des Mini-Aquariums haben die Weltraum-Reise leider nicht überlebt.

Lichtausfall im Mini-Aquarium

Nicht größer und schwerer als ein Getränkekasten: Im Mini-Ökosystem des "Omegahab"-Projekts wurden einzellige Algen Euglena gracilis, auch Augentierchen genannt, die Wasserpflanze Hornblatt (Ceratophyllum demersum), 55 Buntbarsch-Larven (Oreochromis mossambicus), mexikanische Bachflohkrebse (Hyalella azteca) und einige Posthornschnecken (Biomphalaria glabrata) auf ihre Reise ins All geschickt. Biologen und Zoologen der Universitäten Erlangen und Hohenheim haben das aus zwei Kammern bestehende, künstliche Mini-Ökosystem mit eigenem Nährstoff- und Gasaustausch entwickelt. In Schwerelosigkeit sollte dies als bioregeneratives Lebenserhaltungssystem funktionieren. Die Algen und das Hornblatt produzierten dabei den Sauerstoff für die Fische, Krebse und Schnecken. Das von den Tieren freigesetzte Kohlendioxid wiederum haben die Pflanzen in ihrer Photosynthese verwertet - ein geschlossener Kreislauf des Lebens in 575 Kilometern über der Erde. "Damit dieser Kreislauf funktioniert, brauchen die Pflanzen Licht. Das gesamte System scheint bis zum zehnten Tag gut funktioniert zu haben. Dann fiel allerdings die LED-Beleuchtung aus. Dadurch gab es kein Licht im Aquarium mehr und somit auch keinen Sauerstoff für die Buntbarsche, Krebse und Schnecken", erklärt Markus Braun, Omegahab-Projektleiter im DLR Raumfahrtmanagement.

Leben und Sterben im natürlichen Kreislauf

Vom Tod der tierischen "Omegahab"-Bewohner haben die Algen im Mini-Ökosystem profitiert. Nach dem Ausfall der tierischen Lebensformen haben sich die Euglenen stark vermehrt und ihre Lebensweise umgestellt. Sie haben von photoautotroph auf heterotroph umgeschaltet: Als das Ökosystem noch gut funktioniert hat, haben sich die Algen selbst ernährt. Sie haben ihre Biomasse unter Ausnutzung des Lichtes ausschließlich aus anorganischen Stoffen aufgebaut. Nach dem Ausfall der Beleuchtung dienten dann die von den verendeten Fischlarven freigesetzten Nährstoffe den Algen als Nahrungsgrundlage. "Das sind spannende Ergebnisse für die deutschen Forscher. Außerdem stehen uns Videos von den Fischen und Algen zur Auswertung der Bewegungsmuster in Schwerelosigkeit zur Verfügung. Deswegen werten wir Omegahab nicht als Misserfolg. 30 Tage Weltraumaufenthalt für ein solch komplexes Mini-Ökosystem ist nun einmal eine sportliche Herausforderung. Immerhin haben wir für mindestens zehn Tage eine sehr gute Leistung der Anlage dokumentiert. Dass danach eine LED-Platine ausfällt, ist einfach Pech", berichtet Markus Braun.

Probenentnahme erstmals am Landeort möglich

Die Forscher haben direkt nach der Landung der Raumkapsel ihre Proben für die physiologischen und molekularen Auswertungen entnommen. Das für die BION-Missionen zuständige Institut für Biomedizinische Probleme (IBMP) der Russischen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Moskau hat zum ersten Mal bei einer solchen Mission ein Zelt am Landeort aufgebaut, in dem die Wissenschaftler die Proben vor Ort entnehmen konnten. Bereits um 10.35 Uhr Ortszeit hatten die deutschen Forscher "Omegahab" wieder zurück. Insgesamt verlief die BION-M1-Mission durchaus positiv: Die überwiegende Mehrzahl der Experimente ist erfolgreich verlaufen. Wegen seiner Sonnensegel, die die internen Batterien wieder aufluden, kann der auf biologische Experimente in Schwerelosigkeit spezialisierte Satellit länger und in einer größeren Höhe im Orbit bleiben als seine BION-Vorgänger, die zwischen 1973 und 1996 als Forschungsplattformen im All dienten.

.

.

.

.