24.02.2020

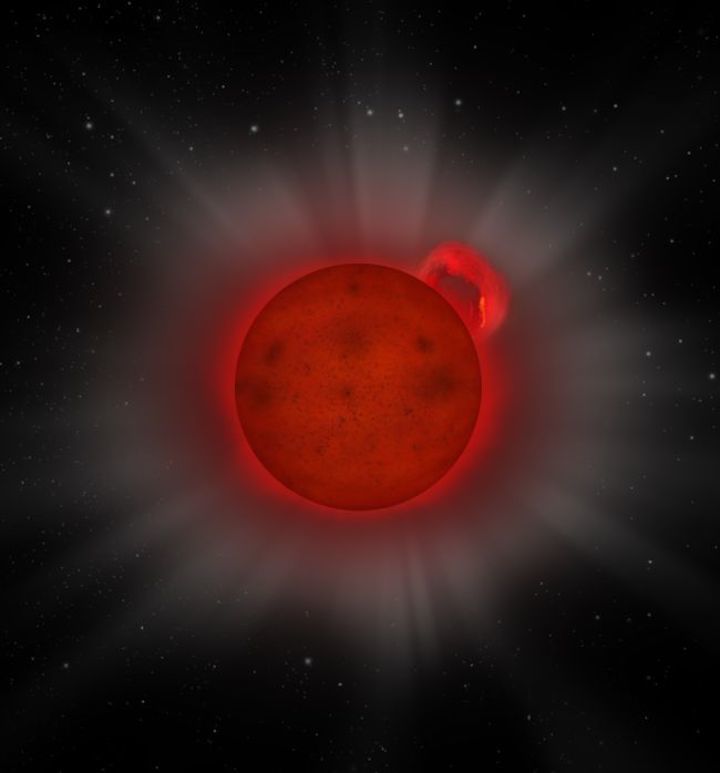

Just like any small child, a tiny star had a huge yet unexpected temper tantrum.

The little star, which is only about 8% of the sun's mass, belched a huge "superflare" of X-rays. It's a strange thing to observe for astronomers, who thought a star that small couldn't create such a large emission in that wavelength of light.

This star is very diminutive by cosmic standards. Known as J0331-27, the star is an L dwarf, the category of star so small that each star's mass is just barely enough to allow for nuclear fusion. ("Failed stars" that don't meet the mass threshold are called brown dwarfs.)

The strange flare also went unnoticed for more than a decade after it happened on July 5, 2008. It was caught by the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton X-ray observatory, but lay in an archive until a search turned up the event. It was quite the event, too, since the little star sent out more than 10 times the energy of the most intense flare sent out by our own sun.

"This is the most interesting scientific part of the discovery, because we did not expect L-dwarf stars to store enough energy in their magnetic fields to give rise to such outbursts," Beate Stelzer, a co-author on a new paper describing the event and an astrophysicist at Germany's Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics and at Italy's Astronomical Observatory of Palermo, said in an ESA statement.

Scientists don't really understand how this flare could have arisen. L dwarfs only have a surface temperature of about 3,320 degrees Fahrenheit (1,830 degrees Celsius). That's about a third of the sun's surface temperature of 10,340 F (5,730 C). At the lower temperatures of an L dwarf, astronomers' models suggested that there isn't enough energy to fuel a star's magnetic field, which would govern the flare. "We just don't know — nobody knows," Stelzer said of why the event happened.

But the astronomers did point out that XMM-Newton observed the star for 40 days and only saw the one flare, which suggests that an L dwarf takes a longer time to build up energy than the sun does — perhaps contributing to the size of the flare.

"A number of similar stars had been seen to emit super flares in the optical part of the spectrum, but this is the first unambiguous detection of such an eruption at X-ray wavelengths," ESA added in the same statement. "The wavelength is significant because it signals which part of the atmosphere the super flare is coming from: optical light comes from deeper in the star's atmosphere, near its visible surface, whereas X-rays come from higher up in the atmosphere."

A paper based on the research was published Feb. 12 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Quelle: SC