16.12.2019

Scientists are scouring the remote Antarctic ice cap for rare meteorites chock-full of iron and holding secrets to the history of our solar system going back some 4.5 billion years.

During a six-week British expedition, the team hopes to find up to five iron meteorites in the five square mile (15 square kilometers) survey area — enough for scientists to examine for key chemical and physical clues to conditions in the early solar system.

Most of the 500 or so meteorites that reach the surface of Earth from space every year are rocks from shattered asteroids, according to NASA — usually ranging from the size of a pebble to the size of a fist.

But roughly 5% of all meteorites that fall to Earth consist of an iron-nickel alloy, known as meteoric iron, and they are thought to come from the cores of planetesimals — small planet-like objects in the early solar system that often smashed together to make larger planets.

"This group of meteorites have an intrinsic scientific interest in that they tell us how small bodies formed and evolved in the early part of solar system history — around 4.5 billion years ago," said meteoriticist Katherine Joy from the University of Manchester, one of the leaders of the Lost Meteorites of Antarcticaexpedition.

On the ice

In theory, Antarctica is a great place to look for meteorites, Joy told Live Science in an email from Rothera Station, a British Antarctic Survey (BAS) base on the Antarctic Peninsula.

"Meteorites are well preserved on the ice and have not been too altered by frequent rainfall, which can partially contaminate them elsewhere," she said. "Being dark in color, they are also easy to spot against the white ice surface."

Meteorites are also often concentrated by ice movements over several years into areas of exposed blue ice — known meteorite stranding zones for that reason. "So we can often collect many samples in quite a small area," she said.

But there is a problem: Iron meteorites have been found in Antarctica far less often than normal — less than 1%of the time.

The British scientists think they now know why:Iron-rich meteorites often heat up during their entry into the atmosphere more so than rocky meteorites, causing them to burrow farther below the ice surface.

"We have hypothesized that these iron meteorites are lying just underneath the surface of the ice out of sight," University of Manchester mathematician Geoff Evatt, one of the leaders of the expedition, told Live Science in an email from Halley Station on the Brunt Ice Shelf. "Hopefully, we can find some this season by using a metal-detector based approach."

Hunting meteorites

A team of five people, including Joy and Evatt, will start looking for iron meteorites near the Shackleton Range of mountains, southeast of the Weddell Sea and about 465 miles (750 km) south of Halley Station, the nearest base.

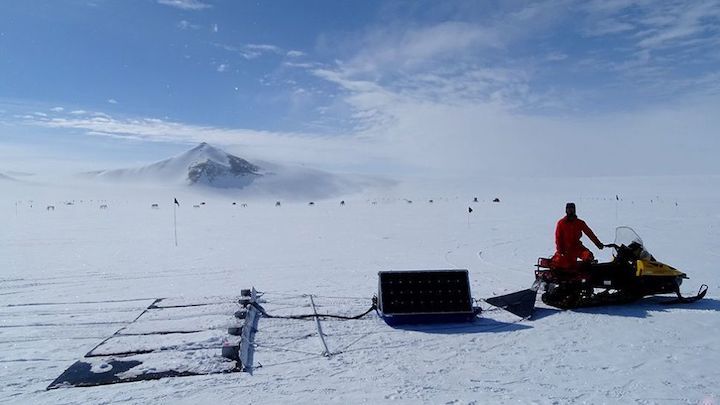

Evatt said the team would take turns using two specially designed wide-array metal detectors, towed by snowmobiles.

Each metal-detecting array features five detectors about 40 inches (1 meter) wide — so the team can search a 32-foot-wide (10 m) swath of the ice as they travel, he said.

The area chosen for the survey is within air-support range of Halley Station, and there are very few surface rocks to slow any towing operations.

Mathematical modeling of the meteorite stranding zones, carried out by University of Manchester mathematician Andrew Smedley, also suggests that the survey area could have a lot of iron meteorites just below the ice surface, he said.

Now, they are ready for a big haul, they said.

Quelle: SC