15.08.2019

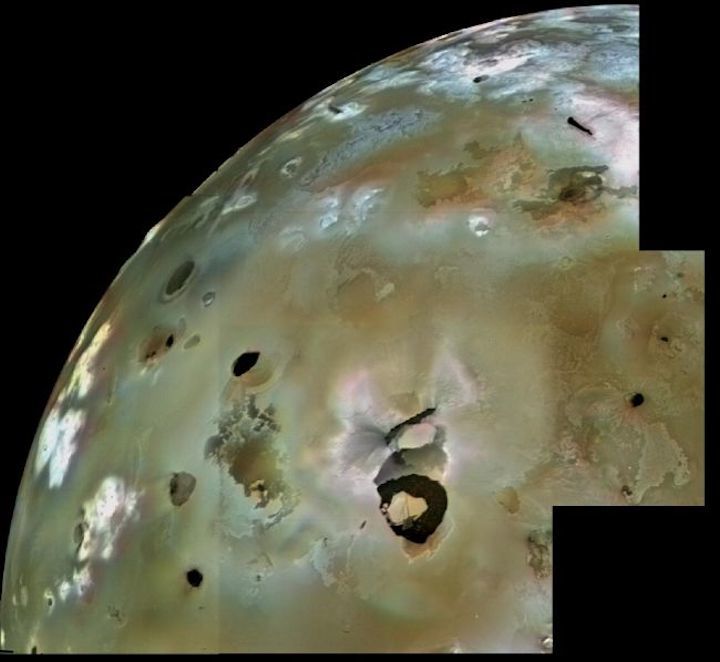

t's stressful to hang out near the king of the solar system, and Jupiter's moon Iobears the scars of that close relationship on its surface, which is pockmarked by a host of volcanoes.

Those volcanoes form because the planet's massive gravity stretches the interior of Io in a process called tidal heating that melts rock into liquid magma, which eventually builds up enough pressure to burst to the surface. A new study examines three decades of observations of the ebb and flow of the largest of those volcanoes, which scientists call Loki Patera, looking for patterns that might tie the volcano's schedule of activity to Io's orbit around Jupiter.

"Some people are expecting Io's volcanoes to do something like this and it's not too surprising," lead author Katherine de Kleer, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology, told Space.com. "But then there are other people who think that volcanoes are so complicated that they wouldn't necessarily follow these orbital trends."

De Kleer and her colleagues started by pinning down the details of Io's orbit, which takes about 1.77 Earth days. That's too fast for scientists to develop a nuanced understanding of the orbit's impacts using Earth-based telescopes, which can only observe when Io is in their line of sight.

But there are other, much slower cycles — on the scale of hundreds of days — that are embedded within that orbit, as other moons pull at Io. Those cycles could also influence the tidal heating that the moon experiences.

"It's been this interesting search for patterns in the volcanic activity; tidal heating should produce volcanism that follows specific patterns," de Kleer said. "So you should have volcanoes that are occurring at specific places on the surface and not at other places, and you might expect them to show specific patterns in time also."

To try to make sense of the volcano, the study authors gathered all the observations they could find of Loki over the past three decades. For much of that timeline, scientists' data was sporadic at best, but in 2013, de Kleer and her colleagues made a concerted effort to maximize observations of Loki.

The result is the most detailed look scientists have ever had of the volcano's activity. "It's the dataset which is the most impressive thing," Julie Rathbun, a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute who wasn't involved in the new research but who also studies Loki, told Space.com. "It's really hard to get all the data we want from the ground."

The other factor that de Kleer and her colleagues focused on, the details of Io's orbit around Jupiter, was less challenging to study. But it's not the sort of factor volcanologists might turn to first if they've been inspired primarily by volcanoes closer to home, which aren't strongly affected by any tidal heating.

"A lot of the geology is based on terrestrial geology and there's not a lot of things on Earth that are driven by tides, so it's not something I think people, especially when studying volcanoes, are used to looking for," Rathbun said. "When studying planets and moons, tides and periodicity are among the most obvious things to measure, they're the easiest things to measure."

A Voyager 1 image shows a plume rising from Loki Patera.

De Kleer and her colleagues were inspired by cycles scientists have noticed in plumes streaming off one of Saturn’s moons, Enceladus, which seem to brighten and dim in conjunction with that moon's orbit.

They found two cycles in Loki's activity that might be influenced by tidal heating: one lasting 454 days and the other 480 days. Both of those numbers are close to cycles in which Io's orbit is tweaked by the influences of its neighbors.

And realistically, that sort of cycle might make more sense in a volcano than a cycle tied directly to an orbital period as fast as Io's. "Those are the timescales that a volcano can actually evolve on," de Kleer said. She and her colleagues think one potential explanation for what's happening at Loki is that the plumbing of the volcano can't respond to tidal heating at the speed of the 1.77-day orbital cycle, leaving only slower cycles to affect the volcano.

Understanding how Loki works isn't just about understanding one massive planet's one weirdo moon. Earth and Io are the only worlds in our solar system where it's easy to study volcanoes, and Earth's aren't strongly influenced by tidal heating, but scientists believe that phenomenon is a vitally important one in the bigger picture of planetary science, in our solar system and beyond.

"This kind of global-scale tidally driven geophysics is just not something that you have on Earth," de Kleer said. "[Io] is kind of this alien world where we have these processes that you're not able to study on Earth, and if we can study them on Io we can broaden our idea of geophysics more generally so that it's less Earth-centric and encompasses more worlds."

De Kleer and her colleagues are hoping to continue regularly checking on Loki in order to sort out how Io's orbital cycles are governing its activity. They calculated out when the volcano could rumble based on each timeline, and within a few years, they're hoping to gather enough data to pin down a better understanding of Loki's dynamics.

"It's going to be a lot of fun when we get close to the predicted times that the brightenings should occur," de Kleer said. "We can watch and we notice right away in the images when Loki starts to brighten, and that's always fun."

The research is described in a paper published May 8 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Quelle: SC