16.05.2019

Troubleshooting of Mars InSight instrument continues

WASHINGTON — Engineers are continuing to work to free an instrument on NASA’s InSight Mars lander that remains stuck just below the surface.

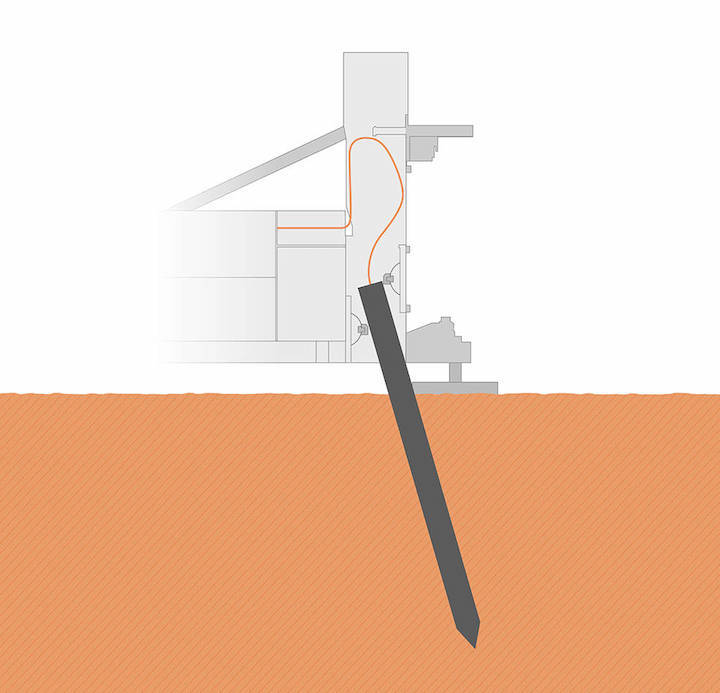

The Heat Flow and Physical Properties Probe (HP3), one of the two main instruments on the spacecraft, features a probe, or “mole,” designed to hammer its way into the surface to a depth of about five meters. Once in place, it will measure how much heat is flowing out of the planet’s interior.

The instrument, placed on the surface weeks after the spacecraft’s landing last November, started the hammering process in late February, but project scientists stopped that work days later when it appeared the mole was stuck about 30 centimeters below the surface. Engineers have since been trying to determine why the mole is stuck and how to get it moving again.

The instrument team identified three potential causes for the mole becoming stuck. The mole may have hit a rock that blocks its progress. The tether trailing behind the mole could be stuck in the instrument’s support structure. Another possibility is that the mole’s hull doesn’t have enough friction with the surrounding regolith to keep it from rebounding when fires its hammer.

That third explanation now appears to be the most likely one. “We’ve already moved one rock away,” noted Pascale Ehrenfreund, chair of the executive board of the German space agency DLR, during a panel discussion about the mission May 14 at the Humans to Mars Summit here. DLR developed the instrument for the InSight mission.

She said it also appeared unlikely that the tether was tangled within the instrument. “It looks like that it’s actually the hull friction that is limited.”

Tilman Spohn, the principal investigator for the instrument, wrote in a May 6 blog post that data collected by InSight’s other main instrument, a seismometer, showed that the mole’s response to the hammering was between that of one bouncing freely and one progressing normally into the surface.

He wrote previously that a lack of friction could be caused by a “duricrust” of regolith at the surface that has a higher cohesion than layers beneath. “If the mole is sitting in the duricrust, its hull may very well have lost friction and upon time, the mole may have widened the hole in the duricust,” he wrote.

Ehrenfreund said the instrument performed some “diagnostic hammering” in the last few days, but that the results of that latest effort was still being analyzed.

She remained optimistic that the mole would be able to get to its desired depth. “All the tests have shown that HP3 is really healthy and operative. We just have to optimize to hammer further down,” she said.

InSight’s seismometer has been free of technical issues, but has encountered a different problem: a lack of seismic activity. “It turns out that Mars indeed is, so far, extremely quiet,” said Robert Fogel, InSight program scientist at NASA Headquarters, on the same panel.

The instrument has detected six seismic events to date, he said, including one “just the other day.” One of them is a likely Marsquake, but a weak one: an estimated magnitude of 2.5 about 150 kilometers from the landing site.

A notable aspect of that quake, he said, is that the train of waves lasted 12 minutes, far longer than any terrestrial earthquake but similar to quakes detected by seismometers on the moon placed there by the Apollo missions. That can be explained if the Martian crust is very shattered, scattering waves and elongating the wave train, he explained. It also suggests that the crust is very dry, since water would “heal” shattered minerals.

Fogel said that despite the limited number of quakes, they still hope to detect stronger events, with magnitudes greater than four. “It’s what we need in order for us to help determine exactly how Mars is stratified: core, mantle and crust,” he said.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 7.06.2019

.

InSight's Team Tries New Strategy to Help the 'Mole'

Scientists and engineers have a new plan for getting NASA InSight's heat probe, also known as the "mole," digging again on Mars. Part of an instrument called the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3), the mole is a self-hammering spike designed to dig as much as 16 feet (5 meters) below the surface and record temperature.

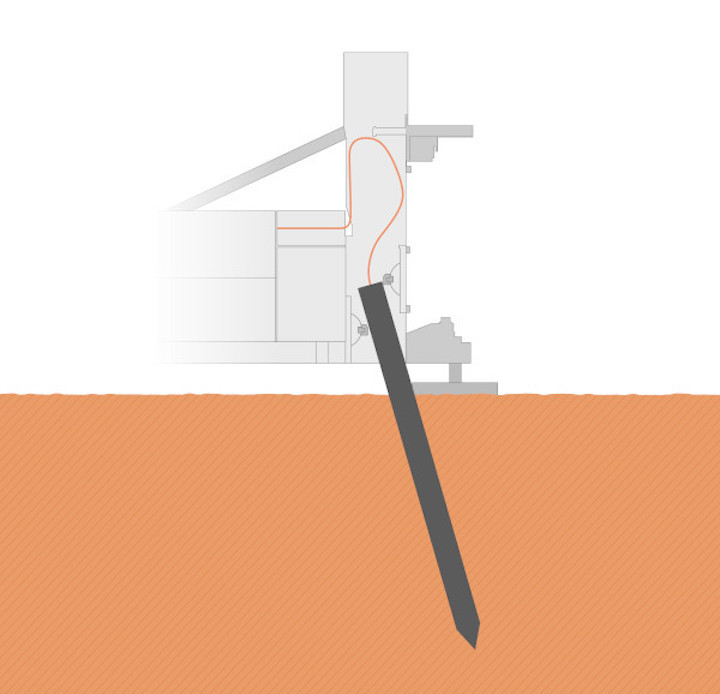

But the mole hasn't been able to dig deeper than about 12 inches (30 centimeters) below the Martian surface since Feb. 28, 2019. The device's support structure blocks the lander's cameras from viewing the mole, so the team plans to use InSight's robotic arm to lift the structure out of the way. Depending on what they see, the team might use InSight's robotic arm to help the mole further later this summer.

HP3 is one of InSight's several experiments, all of which are designed to give scientists their first look at the deep interior of the Red Planet. InSight also includes a seismometer that recently recorded its first marsquake on April 6, 2019, followed by its largest seismic signal to date at 7:23 p.m. PDT (10:23 EDT) on May 22, 2019 - what is believed to be a marsquake of magnitude 3.0.

For the last several months, testing and analysis have been conducted at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, which leads the InSight mission, and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), which provided HP3, to understand what is preventing the mole from digging. Team members now believe the most likely cause is an unexpected lack of friction in the soil around InSight - something very different from soil seen on other parts of Mars. The mole is designed so that loose soil flows around it, adding friction that works against its recoil, allowing it to dig. Without enough friction, it will bounce in place.

Scientists and engineers have a new plan for getting NASA InSight's heat probe, also known as the "mole," digging again on Mars. Part of an instrument called the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3), the mole is a self-hammering spike designed to dig as much as 16 feet (5 meters) below the surface and record temperature.

But the mole hasn't been able to dig deeper than about 12 inches (30 centimeters) below the Martian surface since Feb. 28, 2019. The device's support structure blocks the lander's cameras from viewing the mole, so the team plans to use InSight's robotic arm to lift the structure out of the way. Depending on what they see, the team might use InSight's robotic arm to help the mole further later this summer.

HP3 is one of InSight's several experiments, all of which are designed to give scientists their first look at the deep interior of the Red Planet. InSight also includes a seismometer that recently recorded its first marsquake on April 6, 2019, followed by its largest seismic signal to date at 7:23 p.m. PDT (10:23 EDT) on May 22, 2019 - what is believed to be a marsquake of magnitude 3.0.

For the last several months, testing and analysis have been conducted at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, which leads the InSight mission, and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), which provided HP3, to understand what is preventing the mole from digging. Team members now believe the most likely cause is an unexpected lack of friction in the soil around InSight - something very different from soil seen on other parts of Mars. The mole is designed so that loose soil flows around it, adding friction that works against its recoil, allowing it to dig. Without enough friction, it will bounce in place.

"Engineers at JPL and DLR have been working hard to assess the problem," said Lori Glaze, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division. "Moving the support structure will help them gather more information and try at least one possible solution."

The lifting sequence will begin in late June, with the arm grasping the support structure (InSight conducted some test movements recently). Over the course of a week, the arm will lift the structure in three steps, taking images and returning them so that engineers can make sure the mole isn't being pulled out of the ground while the structure is moved. If removed from the soil, the mole can't go back in.

The procedure is not without risk. However, mission managers have determined that these next steps are necessary to get the instrument working again.

"Engineers at JPL and DLR have been working hard to assess the problem," said Lori Glaze, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division. "Moving the support structure will help them gather more information and try at least one possible solution."

The lifting sequence will begin in late June, with the arm grasping the support structure (InSight conducted some test movements recently). Over the course of a week, the arm will lift the structure in three steps, taking images and returning them so that engineers can make sure the mole isn't being pulled out of the ground while the structure is moved. If removed from the soil, the mole can't go back in.

The procedure is not without risk. However, mission managers have determined that these next steps are necessary to get the instrument working again.

"Moving the support structure will give the team a better idea of what's happening. But it could also let us test a possible solution," said HP3 Principal Investigator Tilman Spohn of DLR. "We plan to use InSight's robotic arm to press on the ground. Our calculations have shown this should add friction to the soil near the mole."

A Q & A with team members about the mole and the effort to save it is at:

https://mars.nasa.gov/news/8444/common-questions-about-insights-mole/?site=insight

JPL manages InSight for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA's Discovery Program, managed by the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the mission.

A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument to NASA, with the principal investigator at IPGP (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris). Significant contributions for SEIS came from IPGP; the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany; the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) in Switzerland; Imperial College London and Oxford University in the United Kingdom; and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain's Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the temperature and wind sensors.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 9.06.2019

.

Robotischer Arm soll Gehäuse anheben und Maulwurf beim Hämmern helfen

- Mangelnde Reibung des umgebenden Marsbodens ist wahrscheinlich der Grund, warum der Marsmaulwurf bisher nicht tiefer vordringen konnte.

- Verdichtung des Marsbodens in der Nähe der Rammsonde mittels des robotischen Arms soll helfen.

- Schwerpunkte: Raumfahrt, Exploration

Es gibt einen neuen Plan, um den Marsmaulwurf des Deutschen Zentrums für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) auf der NASA-Mission InSight zu unterstützen. Der Maulwurf HP3 ist eine Art selbstschlagender Nagel, der bisher etwa 30 Zentimeter tief in den Marsboden vorgedrungen ist. Seit dem 28. Februar 2019 war es nicht mehr möglich, tiefer in den Boden zu gelangen. Tests mit dem Maulwurf auf dem Mars sowie Tests mit Nachbauten der Rammsonde beim DLR in Deutschland und am Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) der NASA in Pasadena/Kalifornien gaben Einblicke in die möglichen Ursachen der Situation. Wahrscheinlich ist der Halt des Maulwurfs im umgebenden Boden unter der geringeren Schwerkraft auf dem Mars nicht ausreichend, wobei sich auch kleine spaltförmige Hohlräume zwischen Maulwurf und Boden ausgebildet haben könnten. Nun planen die Wissenschaftler und Ingenieure der InSight-Mission, die auf dem Maulwurf sitzende Stützstruktur mit dem Roboterarm des Landers wegzuheben. Von dem Gehäuse befreit, kann die Situation genauer betrachtet werden und es wird möglich, die Rammsonde beim weiteren Hämmern direkt mit dem robotischen Arm zu unterstützen.

Der Hubvorgang wird im Juni schrittweise kommandiert. Zunächst wird die Stützstruktur gegriffen. Im Laufe einer Woche wird der Arm dann die Struktur in drei Schritten anheben und Bilder aufnehmen. Mit dem behutsamen Vorgehen wollen die Ingenieure sicherstellen, dass der Maulwurf, der bereits zu Dreivierteln im Boden ist, nicht herausgezogen wird.

"Wir wollen die Stützstruktur anheben, weil wir den Maulwurf unter der Hülle und im Boden bisher nicht sehen können und so auch nicht genau wissen in welcher Situation er sich befindet", sagt der wissenschaftliche Leiter des HP3-Experiments Prof. Tilman Spohn vom DLR-Institut für Planetenforschung. "Ziemlich sicher sind wir uns mittlerweile, dass dem Maulwurf der mangelnde Halt im Boden zu schaffen macht, weil die Reibung des umgebenden Regoliths unter der geringeren Schwerkraft des Mars deutlich schwächer ausfällt als erwartet." Am DLR-Institut für Raumfahrtsysteme in Bremen durchgeführte Tests haben bestätigt, dass dies unter unglücklichen Umständen geschehen kann. Seitlicher Halt und Reibung sind wichtig für den Maulwurf, da der bei jedem Schlag erzeugte Rückstoß durch Reibung am Boden aufgefangen werden muss.

Nach anheben des Gehäuses wollen die Forscher entscheiden, wie sie dem Maulwurf am besten helfen können. "Wir planen den Roboterarm zu nutzen, um nah am Maulwurf auf den Boden zu drücken. Durch die zusätzliche Last erhöht sich der Druck auf den Maulwurf und damit die Reibung an seiner Außenwand", erklärt Spohn. "Unsere Berechnungen am DLR zeigen, dass wir nahe an das Gerät heranmüssen. Unmittelbar über dem Maulwurf, der ja etwas schräg im Boden sitzt, und nahe dran ist die Wirkung am größten. Ohne die Stützstruktur wegzunehmen, hätten wir zu viel Abstand und die Wirkung wäre zu gering."

Behutsames Wegheben der Stützstruktur

Die Stützstruktur des HP3-Experiments wird schrittweise angehoben, da sich im Inneren des Gehäuses Federn befinden, die möglicherweise noch mit dem hinteren Ende des Marsmaulwurfs in Kontakt stehen. "Wenn das der Fall ist, sollten wir vorsichtig beim Anheben sein, damit wir nicht versehentlich die Rammsonde aus dem Boden ziehen", sagt NASA-Ingenieur Troy Hudson. "Falls das passiert, können wir sie nicht wieder zurück in ihr Loch setzen oder sie anderweitig direkt mit dem robotischem Arm anheben. Also heben wir die Stützstruktur nach und nach an und prüfen, dass der Maulwurf nicht mitkommt." Ein Umsetzen des Maulwurfs würde zudem nicht weiterhelfen, selbst wenn der Arm die Raumsonde greifen könnte. "Wir denken, dass die aktuellen Schwierigkeiten am wahrscheinlichsten einem Mangel an Reibung im Mars-Regolith geschuldet sind. Selbst wenn wir also den Marsmaulwurf umsetzen könnten, würde das vermutlich nicht helfen, denn wir hätten an einer anderen Stelle immer noch das gleiche Reibungsproblem", ergänzt Hudson.

Das HP3-Instrument auf der NASA-Mission InSight

Die Mission InSight wird vom Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Kalifornien, im Auftrag des Wissenschaftsdirektorats der NASA durchgeführt. InSight ist eine Mission des NASA-Discovery-Programms. Das DLR steuert zur Mission das Experiment HP3 (Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package) bei. Die wissenschaftliche Leitung liegt beim DLR-Institut für Planetenforschung, welches das Experiment federführend in Zusammenarbeit mit den DLR-Instituten für Raumfahrtsysteme, Optische Sensorsysteme, Raumflugbetrieb und Astronautentraining, Faserverbundleichtbau und Adaptronik, Systemdynamik und Regelungstechnik sowie Robotik und Mechatronik entwickelt und realisiert hat. Daneben sind beteiligte industrielle Partner: Astronika und CBK Space Research Centre, Magson und Sonaca, das Institut für Photonische Technologie (IPHT) sowie die Astro- und Feinwerktechnik Adlershof GmbH. Wissenschaftliche Partner sind das ÖAW Institut für Weltraumforschung und die Universität Kaiserslautern. Der Betrieb von HP3 erfolgt durch das Nutzerzentrum für Weltraumexperimente (MUSC) des DLR in Köln. Darüber hinaus hat das DLR Raumfahrtmanagement mit Mitteln des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Energie einen Beitrag des Max-Planck-Instituts für Sonnensystemforschung zum französischen Hauptinstrument SEIS (Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure) gefördert.

Ausführliche Informationen zur Mission InSight und zum Experiment HP3 finden Sie auf der DLR-Sonderseite zur Mission mit ausführlichen Hintergrundartikeln sowie in der Animation und der Broschüre zur Mission und über den Hashtag #MarsMaulwurf auf dem DLR-Twitterkanal. Aktuell berichtet Prof. Tilman Spohn, leitender Wissenschaftler des HP3-Experiments, in Blogposts über die Aktivitäten des 'Marsmaulwurfs‘.

Quelle: DLR

----

Update: 23.06.2019

.

A Robot Has Been Stuck on Mars for Months

Then, suddenly, it stopped. After traveling 300 million miles to Mars, the probe got stuck just inches below the surface. It has remained wedged there since, but NASA hopes a delicate rescue operation could soon free it.

“We’d hoped to be well into the ground by now,” Smrekar, the deputy principal investigator of the InSight mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told me.

NASA dispatched InSight to Mars to study the interior of the Red Planet, which, even after many decades of missions, scientists still know little about. The mission would help scientists determine what Mars is like on the inside, and whether its guts resemble another rocky planet—our own.

The probe, made up of a spike and a sensor-studded tether, is designed to burrow nearly 16 feet into the surface. That’s deeper than previous instruments have gone “on any other planet, moon, or asteroid,” according to NASA (excluding Earth, of course). The tether was supposed to follow the spike down and measure the heat coming from the planet’s interior. The machine only made it 12 inches. “It initially was making fabulous progress, and then just abruptly stopped moving forward,” Smrekar said.

The team was stunned. Maybe the instrument had hit a rock, they thought. The scientists and engineers of the InSight mission had prepared for such a scenario; during testing before launch, the heat probe, which they call “the mole,” had shown it could break some rocks and even maneuver around others. The team instructed the mole to keep hammering, in case the force shattered the obstacle, but that didn’t help.

Scientists now suspect another culprit: the Martian soil itself. As the probe hammered, loose dirt was supposed to swirl around it, providing friction for its back-and-forth movements. But the soil might have clumped together instead and moved away from the instrument. Eventually, a moat of empty space could have emerged between them. “Some friction is essential for the mechanism to work, as the recoil produced by the mechanism during hammering needs to be absorbed,” says Matthias Grott, a scientist at the German Aerospace Center’s Institute of Planetary Research, which built the instrument for NASA. Without that friction, the probe just bounces in place.

Spacecraft have never encountered such difficult soil on Mars before, and the probe wasn’t designed to handle it. Scientists have since recreated these conditions back on Earth, with a replica of the heat probe and stickier sand; the experiment, in an outcome that is both reassuring and disheartening,showed that the probe could indeed become stuck like this.

The circumstances are certainly unexpected, but not insurmountable. The team could generate some friction by using a scoop on the robotic arm to drop some soil into the space around the probe or apply pressure to the ground.

If only they could see anything.

InSight’s cameras can take pictures of its surroundings to send home, but they don’t have eyes on the problem. The probe arrived in a cylindrical case that holds it steady until it drills itself free, but only made it out so far before becoming stuck. The case now blocks InSight’s view of the probe and the surrounding regolith.

So the InSight team has devised a rather clever plan. They will use the robotic arm to lift the case, little by little, to get a better look at the probe beneath.

It’s a risky operation. If they end up pulling the probe out of the ground, they can’t stick it back in. InSight’s robotic arm was designed to clutch the case, not handle the probe. So they will command the spacecraft to move carefully, like a stop-motion animator adjusting clay after every take: Lift a little, back off, take a picture, beam it home. The spacecraft is scheduled to attempt this maneuver for the first time tomorrow, raising the case a mere five inches. More attempts are planned for next week. With a better view, the team can confirm the problem and determine a fix.

Here’s a look at the robotic hand unfurling in preparation for the procedure, seen in shadows across the Martian surface:

For now, mission staff are trying to look on the bright side. InSight’s other instruments are working fine; in April, the seismometer detected, for the first time in history, a Marsquake. It has even pitched in to provide data about the probe’s unlucky surroundings, recording the rumbling that resulted from its failed hammering attempts. And besides, it’s better to have a jammed probe now, when one end of it is still sticking out of the ground and within reach, than after it goes subterranean. “If the mole were in the ground and hit a rock, there’s nothing we could do to help,” says Troy Hudson, a scientist and engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “The arm isn’t powerful enough to excavate it.”

And the team has already learned something new about the Martian landscape. “If you asked somebody, ‘What’s the soil on Earth like?’ Well, it depends greatly on where you are. Is it beach sand on Hawaii or loamy soil in Arkansas?” Hudson says. “Mars is a lot more homogenous than Earth, but it’s still an entire planet and soil types are going to be different in different locations.”

InSight’s heat probe is not yet lost, but if the rescue mission goes south, it won’t be the first NASA spacecraft to succumb to Mars and its surprises. In 2009, the Spirit rover became trapped in a sandpit and was unable to reach a slope from which to charge its solar-powered panels. Last year, Opportunity, Spirit’s sister rover, met a similar fate when a dust storm of unprecedented size swept across the planet and blocked sunlight from reaching its panels.

Any time a mission doesn’t go exactly as planned, there are scientists and engineers worrying and troubleshooting and pacing back home, wishing they could be there to help. Before Opportunity was declared dead, Keri Bean, a science planner on the mission, told me she dreamt about saving it. “Sometimes I’ll have dreams in the middle of the night. I’m standing there on Mars next to her, and wiping the dust off her lenses,” she said.

The reality is far more frustrating. This week, at a meeting of InSight scientists in Paris, Smrekar listened to a colleague describe a recent test with a replica of the heat probe. It had rained, and a box of sand, playing the role of Martian soil, became damp and sticky. The instrument couldn’t move, so the scientist pressed a finger to the probe, applying a hint of pressure to get it going again. That’s all it took—on Earth. On Mars, NASA needs a breakthrough.

Quelle: The Atlantic