17.01.2019

New Movie Shows Ultima Thule from an Approaching New Horizons

NASA Spacecraft Begins Returning New Images, Other Data from Historic New Year's Flyby

This movie shows the propeller-like rotation of Ultima Thule in the seven hours between 20:00 UT (3 p.m. ET) on Dec. 31, 2018, and 05:01 UT (12:01 a.m.) on Jan. 1, 2019, as seen by the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) aboard NASA's New Horizons as the spacecraft sped toward its close encounter with the Kuiper Belt object at 05:33 UT (12:33 a.m. ET) on Jan. 1.

During this deep-space photo shoot – part of the farthest planetary flyby in history – New Horizons' range to Ultima Thule decreased from 310,000 miles (500,000 kilometers, farther than the distance from the Earth to the Moon) to just 17,100 miles (28,000 kilometers), during which the images became steadily larger and more detailed. The team processed two different image sequences; the bottom sequence shows the images at their original relative sizes, while the top corrects for the changing distance, so that Ultima Thule (officially named 2014 MU69) appears at constant size but becomes more detailed as the approach progresses.

All the images have been sharpened using scientific techniques that enhance detail. The original image scale is 1.5 miles (2.5 kilometers) per pixel in the first frame, and 0.08 miles (0.14 kilometers) per pixel in the last frame. The rotation period of Ultima Thule is about 16 hours, so the movie covers a little under half a rotation. Among other things, the New Horizons science team will use these images to help determine the three-dimensional shape of Ultima Thule, in order to better understand its nature and origin.

The raw images included in the movie are available on the New Horizons LORRI website. New Horizons downlinked the two highest-resolution images in this movie immediately after the Jan. 1 flyby, but the more distant images were sent home on Jan. 12-14, after a week when New Horizons was too close to the Sun (from Earth's point of view) for reliable communications. New Horizons will continue to transmit images – including its closest views of Ultima Thule – and data for the next many months.

Image credits: NASA/Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/National Optical Astronomy Observatory

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 20.01.2019

.

The PI's Perspective: We Did It — The Bullseye Flyby of Ultima Thule!

Ultima Thule as seen in color by New Horizons during its close approach. Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Roman Tkachenko

As I suspect everyone who follows this blog knows, on New Year's Day, the New Horizons team successfully completed the flyby exploration of an ancient Kuiper Belt object we nicknamed Ultima Thule (officially called 2014 MU69).

As a result — and for the first time — a primordial Kuiper Belt object (KBO) has been explored, and now the data have begun to rain down to Earth. A handful of images were sent back during flyby week; then we had to pause Jan. 4-9 because New Horizons, as seen from Earth, slipped into the solar corona (as it does every January), hampering communications. But on Jan. 10 the data began to flow again, and over the next several months, hundreds of images and spectra and other precious Ultima Thule datasets, now stored in New Horizons' solid-state memory, will be sent home.

There are many places to read about the results we've already obtained, but I want to summarize just a few. For a detailed overview of the first science results, see the abstract for my invited talk at the 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, to be held in Houston this March. That report elaborates on several key results, including that Ultima Thule (UT)...

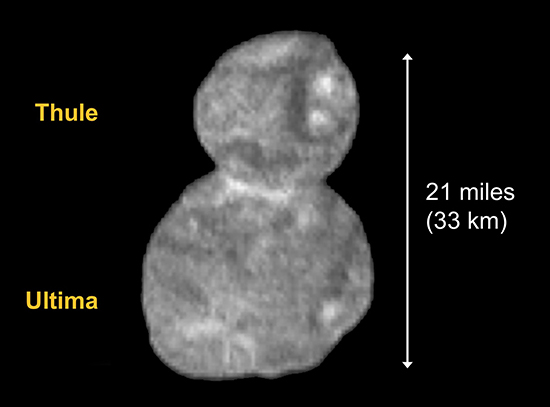

- is clearly a contact binary of two roughly spheroidal worldlets that gently merged billions of years ago, with much to teach us about the formation era of the planets.

- has no satellites or rings or atmosphere (at least in the early data returns).

- is clearly red, but shows little color difference between its two lobes.

- shows a variety of distinct and fascinating surface reflectivity markings, including a remarkably bright "neck" between the two lobes.

And, by the way, my report is just one of 40 abstracts that our team submitted for the conference, containing many, many more findings.

We've nicknamed the two lobes "Ultima" and "Thule," with the larger lobe being called "Ultima" (of course!). Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

So far New Horizons has returned just 1% of all the data it gathered on Ultima Thule. It will send the rest over the next 20 months; but even by late February we'll have far more detailed geologic, color and stereo images than we have now. We'll also have more information on UT's shape and composition, and better constraints on (or maybe even detections of) moons, rings and an atmosphere.

And if that wasn't enough, New Horizons had already resumed observing distant KBOs as well as the radiation, gas and dust environment as it pushes farther into the Kuiper Belt. Notably, in March, we'll look at a KBO called 2014 PN70 — which was one of our alternate flyby targets to Ultima Thule. Don't expect PN70 to be more than a dot in those images, but they should yield valuable information on the object's rotation period, surface properties, shape and any satellites — which we'll compare to Ultima Thule.

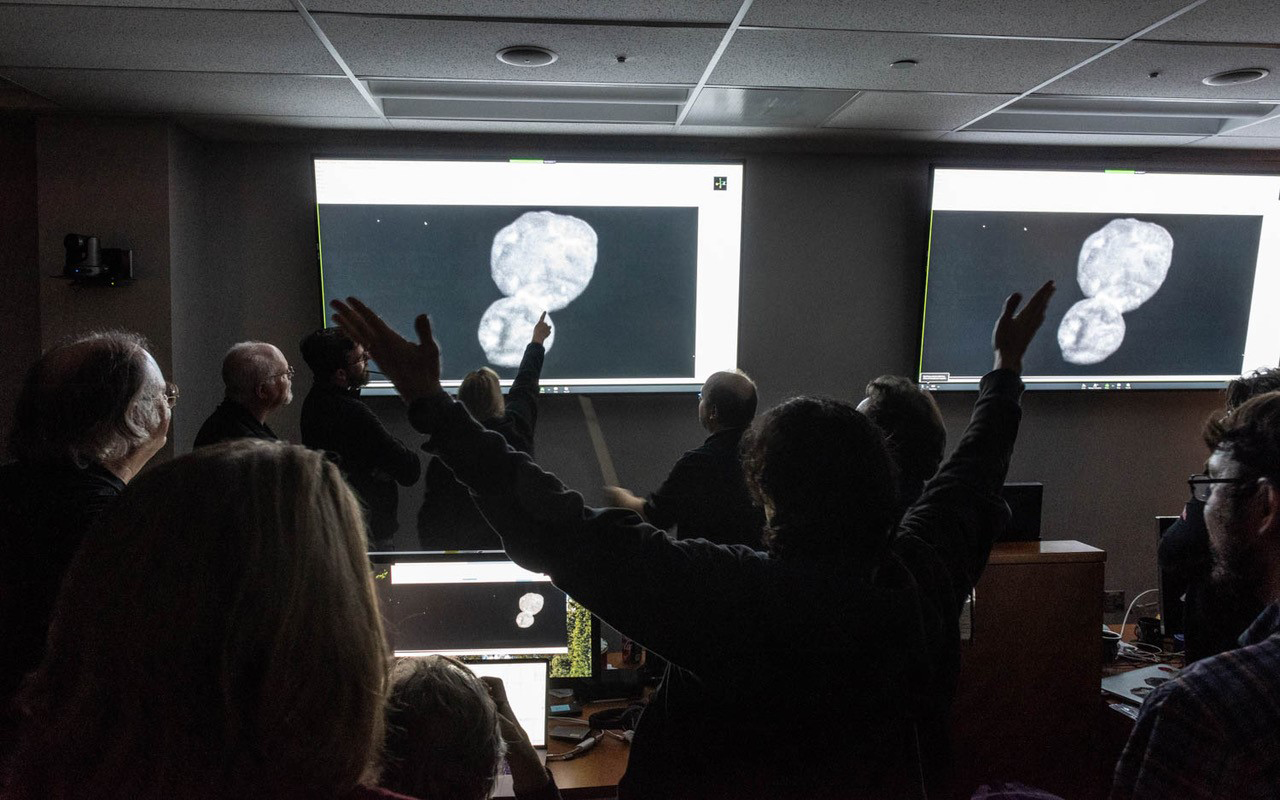

The flyby of Ultima Thule was much more difficult for our spacecraft and mission team than the flight past Pluto. But both team and spacecraft rose to the challenge and conducted a flawless flyby, with record-accurate navigation and spectacularly successful scientific results. There were a lot of dramatic and emotional scenes around the flyby at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, which built New Horizons and manages spacecraft operations. Images of a just few of those moments are shown below.

A few of the many scenes of mission team joy and accomplishment at NASA's New Horizons flyby of the primordial KBO nicknamed Ultima Thule. Images by Henry Throop and Ed Whitman.

And in other news that portends especially well for our hoped-for future extended mission (beginning in late 2021) to explore still farther into the Kuiper Belt: post-flyby engineering results show that we even managed to pocket some extra fuel for future missions that we had reserved for Ultima Thule, but didn't need!

Well, that's my initial post-Ultima Thule flyby report. I plan to write again in the spring. Meanwhile, I hope you'll always keep exploring — just as we do!

Quelle: NASA

+++

PSI Scientist Anticipated "Snowman" Asteroid Appearance

Hartmann visualization of "contact binary" asteroids formed in low-velocity collisions 1978 painting (upper left), 1980 painting (upper right), 1996 painting (lower left) – compared to an image of Ultima Thule by the NASA New Horizons mission (lower right, credit NASA/APL/SWRI).

Tucson, Ariz. -- On Jan. 2, the New Horizons spacecraft made the most distant flyby ever attempted, successfully returning images of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule. While the world is agog at the so-called “snowman” shape of this icy asteroid, the concept is nothing new to PSI scientist and artist, Bill Hartmann. The figure shows paintings that Hartmann made from 1978 to 1996, to illustrate the possible outcome of very low-velocity collisions of distant asteroids. These are compared with the first released color image of Ultima Thule. The story goes back 50 years.

In 1969, University of Arizona astronomers at the Lunar and Planetary Lab (“LPL”), Larry Dunlap and Tom Gehrels, noticed that as the asteroid 624 Hektor, far beyond the main asteroid belt in the region of Jupiter showed extreme changes in brightness as it rotated. In the late 1970s, Hartmann (having recently founded PSI) and Dale Cruikshank (then at the University of Hawaii), observing at 14,000-foot Mauna Kea Observatory, proved that the brightness change was not caused by one side having brighter materials, but rather by a very unusual elongated shape.

Hartmann became intrigued with how such bodies might have formed in the primordial solar system by low-velocity collisions of asteroidal bodies, from which the planets were growing. These still-theoretical bodies were called “contact binary” asteroids – “binary” meaning two bodies, and “contact” indicating that they were touching each other, instead orbiting around each other. PSI’s Stu Weidenschilling published a paper on how the shapes of the two halves of the contact binary might have their shapes distorted, depending on their bulk strengths and the rotation rate of the object.

Hartmann’s 1978 painting showed the contact binary concept with grey colors as found on the Moon. No such bodies had been seen at close range, but Hartmann wanted to depict them. “My astronomical paintings are not just flights of fancy, but a serious attempt to make something both beautiful and realistic out of what we humans have learned about other worlds,” Hartmann said. By 1980, Cruikshank and Hartmann had shown that many bodies in the outermost solar system had a dark, reddish brown color, and his 1980 and 1996 paintings added Hartmann’s estimate of how this color might look.

Ultima Thule was not only the first obvious example of a contact binary structure, but also looked strikingly like Hartmann’s 1996 visualization from 22 years ago. Hartmann happily notes that his 1978 and 1996 paintings show bright material in the “contact zone” where the two bodies collided, and sure enough, the New Horizon spacecraft photo also show bright material there. “We live in an era where scientific findings are being criticized, but if we can predict phenomena we see on other worlds, we must know something about what we are doing,” Hartmann said.

Quelle: PSI

----

Update: 25.01.2019

.

New Horizons' Newest and Best-Yet View of Ultima Thule

The wonders – and mysteries – of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69 continue to multiply as NASA's New Horizons spacecraft beams home new images of its New Year's Day 2019 flyby target.

This image, taken during the historic Jan. 1 flyby of what's informally known as Ultima Thule, is the clearest view yet of this remarkable, ancient object in the far reaches of the solar system – and the first small "KBO" ever explored by a spacecraft.

Obtained with the wide-angle Multicolor Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC) component of New Horizons' Ralph instrument, this image was taken when the KBO was 4,200 miles (6,700 kilometers) from the spacecraft, at 05:26 UT (12:26 a.m. EST) on Jan. 1 – just seven minutes before closest approach. With an original resolution of 440 feet (135 meters) per pixel, the image was stored in the spacecraft's data memory and transmitted to Earth on Jan. 18-19. Scientists then sharpened the image to enhance fine detail. (This process – known as deconvolution – also amplifies the graininess of the image when viewed at high contrast.)

The oblique lighting of this image reveals new topographic details along the day/night boundary, or terminator, near the top. These details include numerous small pits up to about 0.4 miles (0.7 kilometers) in diameter. The large circular feature, about 4 miles (7 kilometers) across, on the smaller of the two lobes, also appears to be a deep depression. Not clear is whether these pits are impact craters or features resulting from other processes, such as "collapse pits" or the ancient venting of volatile materials.

Both lobes also show many intriguing light and dark patterns of unknown origin, which may reveal clues about how this body was assembled during the formation of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago. One of the most striking of these is the bright "collar" separating the two lobes.

"This new image is starting to reveal differences in the geologic character of the two lobes of Ultima Thule, and is presenting us with new mysteries as well," said Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. "Over the next month there will be better color and better resolution images that we hope will help unravel the many mysteries of Ultima Thule."

New Horizons is approximately 4.13 billion miles (6.64 billion kilometers) from Earth, operating normally and speeding away from the Sun (and Ultima Thule) at more than 31,500 miles (50,700 kilometers) per hour. At that distance, a radio signal reaches Earth six hours and nine minutes after leaving the spacecraft.

Image credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

Quelle. NASA

----

Update: 9.02.2019

.

New Horizons' Evocative Farewell Glance at Ultima Thule

Images Confirm the Kuiper Belt Object's Highly Unusual, Flatter Shape

New Horizons took this image of the Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69 (nicknamed Ultima Thule) on Jan. 1, 2019, when the NASA spacecraft was 5,494 miles (8,862 kilometers) beyond it. The image to the left is an "average" of ten images taken by the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI); the crescent is blurred in the raw frames because a relatively long exposure time was used during this rapid scan to boost the camera’s si'gnal level. Mission scientists have been able to process the image, removing the motion blur to produce a sharper, brighter view of Ultima Thule's thin crescent.

An evocative new image sequence from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft offers a departing view of the Kuiper Belt object (KBO) nicknamed Ultima Thule – the target of its New Year's 2019 flyby and the most distant world ever explored.

These aren't the last Ultima Thule images New Horizons will send back to Earth – in fact, many more are to come -- but they are the final views New Horizons captured of the KBO (officially named 2014 MU69) as it raced away at over 31,000 miles per hour (50,000 kilometers per hour) on Jan. 1. The images were taken nearly 10 minutes after New Horizons crossed its closest approach point.

"This really is an incredible image sequence, taken by a spacecraft exploring a small world four billion miles away from Earth," said mission Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of Southwest Research Institute. "Nothing quite like this has ever been captured in imagery."

The newly released images also contain important scientific information about the shape of Ultima Thule, which is turning out to be one of the major discoveries from the flyby.

The first close-up images of Ultima Thule – with its two distinct and, apparently, spherical segments – had observers calling it a "snowman." However, more analysis of approach images and these new departure images have changed that view, in part by revealing an outline of the portion of the KBO that was not illuminated by the Sun, but could be "traced out" as it blocked the view to background stars.

Stringing 14 of these images into a short departure movie, New Horizons scientists can confirm that the two sections (or "lobes") of Ultima Thule are not spherical. The larger lobe, nicknamed "Ultima," more closely resembles a giant pancake and the smaller lobe, nicknamed "Thule," is shaped like a dented walnut.

"We had an impression of Ultima Thule based on the limited number of images returned in the days around the flyby, but seeing more data has significantly changed our view," Stern said. "It would be closer to reality to say Ultima Thule's shape is flatter, like a pancake. But more importantly, the new images are creating scientific puzzles about how such an object could even be formed. We've never seen something like this orbiting the Sun."

The departure images were taken from a different angle than the approach photos and reveal complementary information on Ultima Thule's shape. The central frame of the sequence was taken on Jan. 1 at 05:42:42 UT (12:42 a.m. EST), when New Horizons was 5,494 miles (8,862 kilometers) beyond Ultima Thule, and 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion kilometers) from Earth. The object's illuminated crescent is blurred in the individual frames because a relatively long exposure time was used during this rapid scan to boost the camera's signal level – but the science team combined and processed the images to remove the blurring and sharpen the thin crescent.

Many background stars are also seen in the individual images; watching which stars "blinked out" as the object passed in front them allowed scientists to outline the shape of both lobes, which could then be compared to a model assembled from analyzing pre-flyby images and ground-based telescope observations. "The shape model we have derived from all of the existing Ultima Thule imagery is remarkably consistent with what we have learned from the new crescent images," says Simon Porter, a New Horizons co-investigator from the Southwest Research Institute, who leads the shape-modeling effort.

"While the very nature of a fast flyby in some ways limits how well we can determine the true shape of Ultima Thule, the new results clearly show that Ultima and Thule are much flatter than originally believed, and much flatter than expected," added Hal Weaver, New Horizons project scientist from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. "This will undoubtedly motivate new theories of planetesimal formation in the early solar system."

The images in this sequence will be available on the New Horizons LORRI website this week. Raw images from the camera are posted to the site each Friday.

But as more data were analyzed, including several highly evocative crescent images taken nearly 10 minutes after closest approach, a "new view" of the object's shape emerged. Ultima more closely resembles a "pancake," and Thule a "dented walnut."

The bottom view is the team's current best shape model for Ultima Thule, but still carries some uncertainty as an entire region was essentially hidden from view, and not illuminated by the Sun, during the New Horizons flyby. The dashed blue lines span the uncertainty in that hemisphere, which shows that Ultima Thule could be either flatter than, or not as flat as, depicted in this figure.

The movie then rotates to a side-view that illustrates what New Horizons might have seen had its cameras been pointing toward Ultima Thule only a few minutes after closest approach. While that wasn’t the case, mission scientists have been able to piece together a model of this side-view, which has been at least partially confirmed by a set of crescent images of Ultima Thule (link). There is still considerable uncertainty in the sizes of “Ultima” (the larger section, or lobe) and “Thule” (the smaller) in the vertical dimension, but it’s now clear that Ultima looks more like a pancake than a sphere, and that Thule is also very non-spherical.

The rotation in this animation is not the object’s actual rotation, but is used purely to illustrate its shape.

Ultima Thule latest: less Star Wars, more Star Trek

Images from New Horizons reveal unexpected aspects of the Kuiper Belt object. Richard A Lovett reports.

When NASA’s New Horizons Spacecraft got its first good views of Ultima Thule, the 32-kilometre-long Kuiper Belt object it zoomed by on 1 January 2019, science fiction fans thought it looked remarkably like BB-8, the rolling droid of Star Wars fame.

Closer views made it look more like a frowning snowman.

But now, as images come back from a third angle, it looks more like a spaceship from the Star Trek franchise.

Initially, the object – at 6.6 billion kilometres away, the most distant thing ever visited by humanity – looked like two spheres joined by a narrow “neck”.

But the new images, released in early February, reveal a different profile, considerably more flattened.

It’s possible to see a great many shapes in them, ranging from the Starship Enterprise at the start of a saucer separation manoeuvre to what the project’s official release more conservatively describes as a pancake merged to a dented walnut.

The images were taken nearly 10 minutes after New Horizons’ closest approach, when the fast-moving spacecraft was already looking back from a range of almost 9000 kilometres.

From that angle, all that was visible was a thin crescent, somewhat like the new moon seen from Earth – except this new moon is wing-shaped due to Ultima Thule’s two lobes.

The curvature of the wings was itself enough to prove that Ultima Thule’s lobes are flattened, not spherical. But this was confirmed by watching how the dark parts of the object blocked out background stars during a sequence of 14 such images. That allowed the scientists to trace out the rest of its silhouette, even though most of its surface was too dark to be seen.

“We had an impression of Ultima Thule based on the limited number of images returned in the days around the flyby,” says Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator, “but [this] has significantly changed our view.”

Diagram showing the "old" and "new" approximations of the shape of Ultima Thule.

It also poses a puzzle for scientists trying to unravel the mysteries of the early Solar System. “The new images are creating scientific puzzles about how such an object could even be formed,” Stern says. “We’ve never seen something like this orbiting the sun.”

Hal Weaver, a New Horizons project scientist from Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, US, adds that Ultima Thule’s bizarre shape is almost certainly a relic from its formation 4.5 billion years ago.

“We think Ultima Thule has changed very little since it formed,” he says.

Its shape, he adds, may reflect the way in which each of the two lobes formed before they merged, possibly revealing information about asymmetries in the processes that formed them. But, he adds, “the details will take months to sort out”.

The elongated shapes also mean that the two lobes had less angular (or rotational) momentum when they merged than they would have had if they were spherical.

That, Weaver says, makes it easier to figure out how the merger happened in concert with a law of physics known as conservation of angular momentum, which requires that the rotational momentum the two objects had before they merged had to have gone somewhere, rather than being lost entirely.

(One theory is that any excess was carried away by one or more tiny moons, yet to be found.)

Meanwhile there are still some uncertainties about Ultima Thule’s true shape, which might be either flatter or not as flat as the current estimate.

“The number of look angles are limited for such a fast flyby,” Weaver says, “but we’re squeezing out as much as we can, using all the available evidence.”

And, he adds: “We’re still waiting for more images, which should allow us to further refine the shape. But the limited range of viewing directions and the fact that one hemisphere of Ultima Thule was never illuminated by the Sun will constrain how well we can do.”

Ultima Thule, filmed by New Horizons from 9000 kilometres away.

Quelle: COSMOS

-----

Update: 24.02.2019

.

Ultimate Ultima: New Horizons team shares sharpest view of space snowman

The scientists behind NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft have released the sharpest possible view of the mission’s latest target, a smooshed-in cosmic snowman known as 2014 MU69 or Ultima Thule.

New Horizons captured gigabytes’ worth of imagery and data as it flew past the icy object, more than 4 billion miles from Earth in the Kuiper Belt, a ring of primordial material on the edge of our solar system. It’s taken weeks to send back detailed data for processing, but now the team says they’ve gotten the best close-up view of Ultima that they’ll ever get.

The best pictures were taken from a distance of 4,109 miles, just six and a half minutes before the time of closest approach at 12:33 a.m. ET Jan. 1 (9:33 p.m. PT Dec. 31). By processing multiple images, the team was able to sharpen image resolution to about 110 feet per pixel.

Principal investigator Alan Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, said the imaging campaign hit the “bull’s-eye.”

“Getting these images required us to know precisely where both tiny Ultima and New Horizons were — moment by moment – as they passed one another at over 32,000 miles per hour in the dim light of the Kuiper Belt, a billion miles beyond Pluto,” Stern said today in a news release. “This was a much tougher observation than anything we had attempted in our 2015 Pluto flyby.”

The processing brings out surface details that weren’t readily apparent in earlier images. Among them are several bright, enigmatic, roughly circular patches of terrain. The picture also provides a better look at dark pits near the boundary between Ultima’s sunlit and shadowed sides.

“Whether these features are craters produced by impactors, sublimation pits, collapse pits, or something entirely different, is being debated in our science team,” John Spencer, deputy project scientist from SwRI, said in the news release.

Stern said some of the surface features suggest that Ultima is “unlike any object ever explored before.”

Ultima is thought to represent a contact binary object consisting of material that’s been little changed since the early days of the solar system. From a head-on perspective, Ultima looks like two snowballs that have been stuck together to create a 19-mile-tall snowman (or the BB-8 droid from “Star Wars”). But an analysis of image data captured from the side reveals that the two lobes of the object are actually shaped more like a pancake stuck onto the side of a walnut.

Since the New Year’s encounter, New Horizons has traveled tens of millions of miles beyond Ultima. Mission operations manager Alice Bowman of Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory reports that the spacecraft is continuing to operate flawlessly.

It’s expected to take another year and a half to send back all the data that New Horizons collected during the flyby, and by that time the mission team may well have selected another target for the probe to survey in the Kuiper Belt.

Ultima Thule in 3D

Cross your eyes and break out the 3D glasses! NASA’s New Horizons team has created new stereo views of the Kuiper Belt object nicknamed Ultima Thule – the target of the New Horizons spacecraft’s historic New Year’s 2019 flyby, four billion miles from Earth – and the images are as cool and captivating as they are scientifically valuable.

The 3D effects come from pairing or combining images taken at slightly different viewing angles, creating a “binocular” effect, just as the slight separation of our eyes allows us to see three-dimensionally. For the images on this page, the New Horizons team paired sets of processed images taken by the spacecraft’s Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) at 5:01 and 5:26 Universal Time on Jan. 1, from respective distances of 17,400 miles (28,000 kilometers) and 4,100 miles (6,600 kilometers), offering respective original scales of about 430 feet (130 meters) and 110 feet (33 meters) per pixel.

The viewing direction for the earlier sequence was slightly different than the later set, which consists of the highest-resolution images obtained with LORRI. The closer view offers about four times higher resolution per pixel but, because of shorter exposure time, lower image quality. The combination, however, creates a stereo view of the object (officially named 2014 MU69) better than the team could previously create.

“These views provide a clearer picture of Ultima Thule’s overall shape,” said mission Principal Investigator Alan Stern, from Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, “including the flattened shape of the large lobe, as well as the shape of individual topographic features such as the "neck" connecting the two lobes, the large depression on the smaller lobe, and hills and valleys on the larger lobe.”

"We have been looking forward to this high-quality stereo view since long before the flyby,” added John Spencer, New Horizons deputy project scientist from SwRI. “Now we can use this rich, three-dimensional view to help us understand how Ultima Thule came to have its extraordinary shape."

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, designed, built and operates the New Horizons spacecraft, and manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. The MSFC Planetary Management Office provides the NASA oversight for the New Horizons. Southwest Research Institute, based in San Antonio, directs the mission via Principal Investigator Stern, and leads the science team, payload operations and encounter science planning. New Horizons is part of the New Frontiers Program managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.