23.11.2018

ESA’s Mars Express has imaged an intriguing part of the Red Planet’s surface: a rocky, fragmented, furrowed escarpment lying at the boundary of the northern and southern hemisphere.

This region is an impressive example of past activity on the planet and shows signs of where flowing wind, water and ice once moved material from place to place, carving out distinctive patterns and landforms as it did so.

Mars is a planet of two halves. In places, the northern hemisphere of the planet sits a full few kilometres lower than the southern; this clear topographic split is known as the martian dichotomy, and is an especially distinctive feature on the Red Planet’s surface.

Northern Mars also displays large areas of smooth land, whereas the planet’s southern regions are heavily pockmarked and scattered with craters. This is thought to be the result of past volcanic activity, which has resurfaced parts of Mars to create smooth plains in the north – and left other regions ancient and untouched.

The star of this Mars Express image, a furrowed, rock-filled escarpment known as Nili Fossae, sits at the boundary of this north-south divide. This region is filled with rocky valleys, small hills, and clusters of flat-topped landforms (known as mesas in geological terms), with some chunks of crustal rock appearing to be depressed down into the surface creating a number of ditch-like features known as graben.

Mars Express view of Nili Fossae

As with much of the surrounding environment, and despite Mars’ reputation as a dry, arid world today, water is believed to have played a key role in sculpting Nili Fossae via ongoing erosion. In addition to visual cues, signs of past interaction with water have been spotted in the western (upper) part of this image – instruments such as Mars Express’ OMEGA spectrometer have spotted clay minerals here, which are key indicators that water was once present.

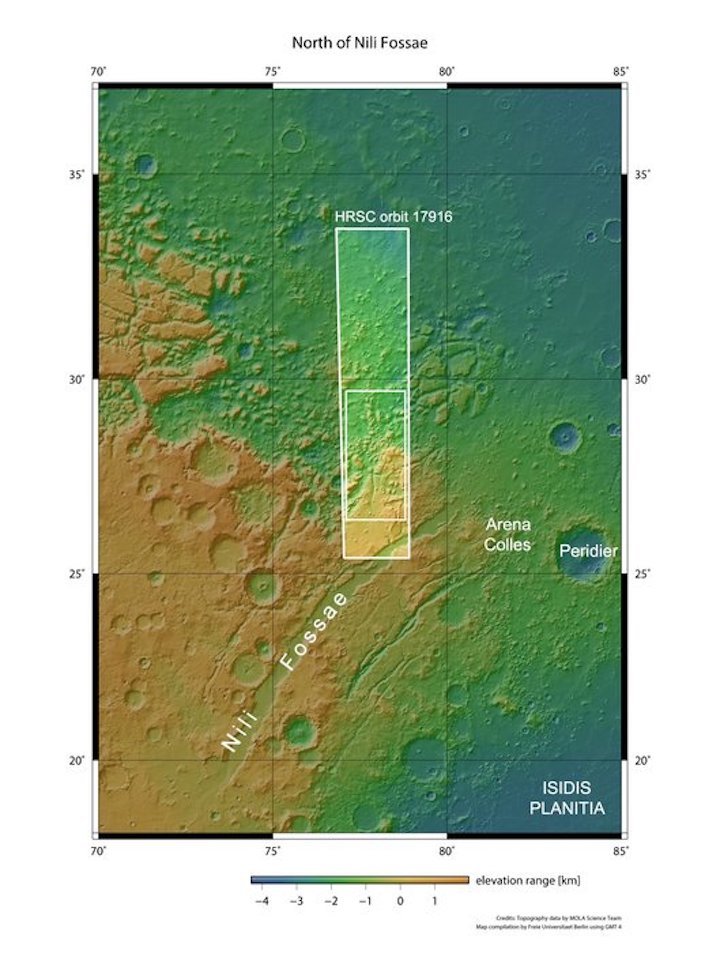

Topography of Nili Fossae

The elevation of Nili Fossae and surroundings, shown in the topographic view above, is somewhat varied; regions to the left and lower left (south) sit higher than those to the other side of the frame (north), illustrating the aforementioned dichotomy. This higher-altitude terrain appears to consist mostly of rocky plateaus, while lower terrain comprises smaller rocks, mesas, hills, and more, with the two sections roughly separated by erosion channels and valleys.

This split is thought to be the result of material moving around on Mars hundreds of millions of years ago. Similar to glaciers on Earth, flows of water and ice cut through the martian terrain and slowly sculpted and eroded it over time, also carrying material along with them. In the case of Nili Fossae, this was carried from higher areas to lower ones, with chunks of resistant rock and hardy material remaining largely intact but shifting downslope to form the mesas and landforms seen today.

Nili Fossae in 3D

The shapes and structures scattered throughout this image are thought to have been shaped over time by flows of not only water and ice, but also wind. Examples can be seen in this image in patches of the surface that appear to be notably dark against the ochre background, as if smudged with charcoal or ink. These are areas of darker volcanic sand, which have been transported and deposited by present-day martian winds. Wind moves sand and dust around often on Mars’ surface, creating rippling dune fields across the planet and forming multi-coloured, patchy terrain like Nili Fossae.

The data comprising this image were gathered by Mars Express’ High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) on 26 February 2018.

ESA’s Mars Express was launched in 2003. As well as producing striking views of the martian surface such as this, the mission has shed light on many of the planet’s biggest mysteries – and helped to build the picture of Mars as a planet that was once warmer, wetter and potentially habitable. Read more about the past 15 years of Mars Express, and what the mission has discovered so far, here.

+++

FROM HORIZON TO HORIZON: CELEBRATING 15 YEARS OF MARS EXPRESS

Fifteen years ago, ESA’s Mars Express was launched to investigate the Red Planet. To mark this milestone comes a striking view of Mars from horizon to horizon, showcasing one of the most intriguing parts of the martian surface.

On 2 June 2003, the Mars Express spacecraft lifted off from Baikonur, Kazakhstan, on a journey to explore our red-hued neighbouring planet. In the 15 years since, it has become one of the most successful missions ever sent to Mars, as demonstrated by this image of the region known as the Tharsis province, shown here in its full glory.

Mammoth volcanoes, sweeping canyons, fractured ground: Tharsis is one of the most geologically interesting and oft-explored parts of the planet’s surface. Once an incredibly active region, displaying both volcanism and the shifting crustal plates of tectonics, it hosts most of the planet’s colossal volcanoes – the largest in the Solar System.

This view, taken by the High Resolution Stereo Camera aboard Mars Express in October 2017, shows Tharsis in all its glory.

It sweeps from the planet’s upper horizon — marked by the faint blue haze at the top of the frame — down across a web of pale fissures named Noctis Labyrinthus (a part of Valles Marineris stretching to the upper left corner of the image), Ascraeus and Pavonis Mons (two of Tharsis’ four great volcanoes at more than 20 km high), and finishes at the planet’s northern polar ice cap (in this perspective, North is to the lower left).

Sitting near Mars’ equator, Tharsis covers roughly a quarter of the martian surface and is thought to have a played an important role in the planet’s history. It straddles the boundary between Mars’ southern highlands and northern lowlands.

Elevation on Mars is defined relative to where the gravity is the same as the average at the martian equator. This serves as a type of ‘sea-level’, even though are no seas.

Most of Tharsis is higher than average, at between 2 and 10 km high. The province likely formed as mushroom-shaped plumes of molten rock (magma) swelled up beneath the viscous surface over time, creating seeping flows, magma chambers, and large, rocky provinces – like Tharsis – and feeding ongoing volcanism from below.

Tharsis is also connected to the formation of the famous Valles Marineris, which is some four times longer and deeper than the Great Canyon in Arizona, USA, and the most extensive canyon system discovered in the Solar System. This is partly visible as the dark tendrils to the upper left of the image.

As magma swelled up beneath the crust to create the Tharsis province, the tension caused some areas to rupture and fracture. Molten rock then flooded these fractures and destabilised and separated regions of the crust yet further, resulting in both the wide, substantial troughs and fissures that comprise modern-day Valles Marineris, and the web-like Noctis Labyrinthus that sits at the canyon system’s western end.

Captured in the new view are volcanoes Pavonis Mons (top right), Ascraeus Mons (just below), Alba Mons (to the bottom left), and a small sliver of Olympus Mons (to the lower right, continuing out of frame) in caramel hues; a view of the region with labels is provided here. The location of this slice of Mars’ surface is also shown in a context map of the planet and in a topographic context.

This latter view shows higher areas of the surface in red and lower ones in blue-green, illustrating the difference in altitude between the northern and southern regions of Mars.

Mars Express has been revealing the beauty and variety of Mars for 15 years, and is still going strong.

Alongside myriad striking views such as this, the spacecraft has produced global maps tracing the planet’s geologic activity, water, volcanism, and minerals, and provided enough data to construct thousands of 3D images of the surface. It has studied immense volcanoes, canyons, polar ice caps, and ancient impact craters; probed the sub-surface with radar; and explored the martian atmosphere, finding signs of ozone and methane, fleeting cloud layers, and mighty dust storms. The spacecraft has witnessed charged particles escaping to space, and examined Mars’ moons Phobos and Deimos. It has successfully identified dried-up river valleys, traces of catastrophic floods, and buried glaciers.

The past 15 years of observations from Mars Express have significantly contributed to the newly emerging picture of Mars as a once-habitable planet, with warmer and wetter epochs that may have once acted as oases for ancient martian life. These findings have paved the way for missions dedicated to hunting for signs of life on the planet, such as ESA and Roscosmos’s two-mission ExoMars programme.

Meanwhile, on board Mars Express, an innovative software patch has recently rejuvenated the spacecraft.

After the successful activation of new software loaded on the spacecraft on 16 April, followed by a series of in-flight tests, Mars Express resumed science operations on 27 April. The new software, developed by ESA, was needed to compensate for the potential old-age run-down of the satellite's six gyroscopes, which measure how much Mars Express rotates about any of its three axes. Since 16 May, the spacecraft has been operating with its gyros mostly switched off. Fine-tuning of the new software will take place over the coming months.

This implementation is a major operational milestone for the mission, as it gives Mars Express an extended lifeline, possibly through the mid-2020s.

Quelle: ESA