17.11.2018

Today, most of the water on Mars is locked away in frozen ice caps. But billions of years ago it flowed freely across the surface, forming rushing rivers that emptied into craters, forming lakes and seas. New research led by The University of Texas at Austin has found evidence that sometimes the lakes would take on so much water that they overflowed and burst from the sides of their basins, creating catastrophic floods that carved canyons very rapidly, perhaps in a matter of weeks.

The findings suggest that catastrophic geologic processes may have had a major role in shaping the landscape of Mars and other worlds without plate tectonics, said lead author Tim Goudge, a postdoctoral researcher at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences who will be starting as an assistant professor at the school in 2019.

“These breached lakes are fairly common and some of them are quite large, some as large as the Caspian Sea,” said Goudge. “So we think this style of catastrophic overflow flooding and rapid incision of outlet canyons was probably quite important on early Mars’ surface.”

The research was published Nov. 16 in the journal Geology. Co-authors include NASA scientist Caleb Fassett and Jackson School Professor and Associate Dean of Research David Mohrig.

From studying rock formations from satellite images, scientists know that hundreds of craters across the surface of Mars were once filled with water. More than 200 of these “paleolakes” have outlet canyons tens to hundreds of kilometers long and several kilometers wide carved by water flowing from the ancient lakes.

However, until this study, it was unknown whether the canyons were gradually carved over millions of years or carved rapidly by single floods.

Using high-resolution photos taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter satellite, the researchers examined the topography of the outlets and the crater rims and found a correlation between the size of the outlet and the volume of water expected to be released during a large flooding event. If the outlet had instead been gradually whittled away over time, the relationship between water volume and outlet size likely wouldn’t hold, Goudge said.

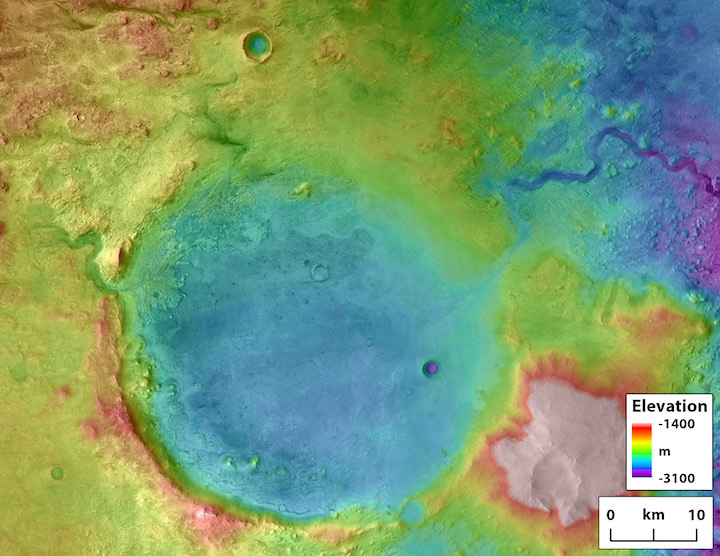

In total, the researchers examined 24 paleolakes and their outlet canyons across the Red Planet. One of the paleolakes examined in the study, Jezero Crater, is a potential landing site for NASA’s Mars 2020 rover mission to look for signs of past life. Goudge and Fassett proposed the crater as a landing site based on prior studies that found it held water for long periods in Mars’ past.

While massive floods flowing from Martian craters might sound like a scene in a science fiction novel, a similar process occurs on Earth when lakes dammed by glaciers break through their icy barriers. The researchers found that the similarity is more than superficial. As long as gravity is accounted for, floods create outlets with similar shapes whether on Earth or Mars.

“This tells us that things that are different between the planets are not as important as the basic physics of the overflow process and the size of the basin,” Goudge said. “You can learn more about this process by comparing different planets as opposed to just thinking about what’s occurring on Earth or what’s occurring on Mars.”

Although big floods on Mars and Earth are governed by the same mechanics, they fit into different geological paradigms. On Earth, the slow-and-steady motion of tectonic plates dramatically changes the planet’s surface over millions of years. In contrast, the lack of plate tectonics on Mars means that cataclysmic events — like floods and asteroid impacts — quickly create changes that can amount to near permanent changes in the landscape.

“The landscape on Earth doesn’t preserve large lakes for a very long time,” Fassett said. “But on Mars … these canyons have been there for 3.7 billion years, a very long time, and it gives us insight into what the deep time surface water was like on Mars.”